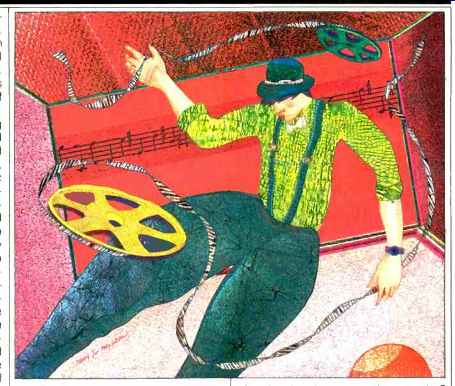

SPOOLS OF THOUGHT

An audio biography, I find, is entirely too much like paying bills.

After considerable effort in many past issues of this magazine, I still find myself some 40 years behind.

Just as well! Like antiques, old news is good news, and the older the better, if only for the novelty of it.

It was shortly before I began writing for this magazine in mid-1947 that I took a momentous step forward toward Audio with a capital A--I sallied forth, cash in hand, and bought a magnetic recorder. I kept it all of two weeks be fore I junked it. This wasn't a disc recorder with a magnetic cutting head weighing 4 ounces or so, which was in general use at the time. I was already far beyond that with my ultra-modern wide-range (up to 6 kHz) crystal cut ting head, dating from 1940. That crystal head was much lighter too, weighing maybe as little as an ounce (we had not yet stepped down to the gram weight scale). What I bought in mid-1947 was a machine that would record in a magnetic medium, the hope of the future and the basis for so much of what we call audio today.

During the years of World War II when I worked in FM in New York City, there were frequent advertisements boasting of a sensational new kind of home sound via wire which would be introduced "after the duration"--in other words, after the end of the war. I insist, positively (by memory), that the product was to be the fabulous Lear wire recorder. You ask Lear now, they'll probably deny it. But that is what I remember, because-after too many dismal experiences with faulty 33-rpm lacquers-I was fascinated by the thought of a recording medium that would just go on and on, maybe even longer than the approximately 15 minutes then possible on a 16-inch professional disc at 33 rpm.

Lear, if it was Lear, kept at it. The "duration" was bound to end sooner or later, and then all these much-advertised products would spring upon the market, full-fledged, and we would all rush out in a perfect frenzy of buying.

Nice to think ahead that way! But the war ground more deeply, and rationing got more strict. Only 5 gallons of gas were allowed per week for ordinary car owners' gas guzzlers, left over from prewar days. Even phonograph discs were rationed-you had to turn in an old shellac disc for every new one you bought, as there was no shellac coming from the Far East.

Came the two successive V-days, first V-E and then, in mid-summer 1945, V-J and the end. Buying spree? We were much too busy celebrating. I was stuck in Times Square on that later date along with about a million other people; I recall beginning to tip over, so to speak, under the mass human pressure, but I never made it to the ground. Instead, I remained suspended at a 45° angle, held up by acres of bodies for at least an hour, absolutely helpless. It was exhilarating.

As some remember, nothing really happened for the general public for a year and more after V-J Day. It took that long to unwind and untangle the war economy and get the old prewar manufactures back into production virtually as was, years before. New products mostly had to wait. And that included just about everything that might have been called "audio," if that word had been in common use. So it shouldn't be surprising that 1947 was the beginning of practically everything new, advertised and unadvertised.

Where was the Lear? Where was my after-the-duration magnetic recorder? Nary a word! Don't ask me what happened, unless maybe the Lear people discovered jet transportation about then. I don't remember ever hearing about a Lear magnetic recorder again.

Meanwhile, another manufacturer had taken over the idea for a "consumer" recorder of the same sensational type, and presently it appeared, from an outfit already (as I remember) very well known-Webcor. For many of our earlier years, the turntables made by that company were standard fare in thousands of American homes.

Wire recorder? Wow! Sensational! Superlatives are what any gutsy youngster would have employed to ex press his enthusiasm.

I can see the Webcor wire recorder in my mind's eye, and the sight does not please me. A bilious speckled maroon (well, my eye is prejudiced, after all), just a big, unwieldy suitcase thing, outwardly not unlike the earlier so called portable phonographs of the Liberty phone persuasion, also Magnavox. (Those phonographs, a.c./d.c. for the big cities that still had mainly d.c. current, were all the rage for college students and the like who kept moving around and wanted a "little" phono-graph-ugh-to take with them. I rented one in college-- d.c.--and I can hear its muffled, boomy sound to this moment. I could just about lift it.) I do hate to tell you what happened with that wire recorder. Before I get into it, though, I must hastily remind you that on the professional side, be fore tape, there was a workable wire recorder from the Armour people, complete with capstan drive, which did satisfactory things of a useful nature for a while before such early tape machines as the Ampex arrived. Wire re cording was wonderfully ingenious. As a matter of fact, it was already an old principle, going back to the famed Valdemar Poulsen, the first person to try to record sound using variable magnetism on a continuously passing magnetic medium. That was at the turn of the century. With some horrendous problems well solved, a professional wire recorder could be, and was, produced. But the consumer product was another matter.

In today's money, the Webcor wire recorder might have cost, at a guess, some $600. That's not hay, and it wasn't then, even if the actual sum was around $50. For me, in my most impecunious period, it was a real gamble, spending such a sum on something brand-new and untried-but I had to have it. Thank Lear for that. Diverted advertising, you might say.

The home-type wire recorder, I immediately found, was fatally flawed in one ghastly respect: It was strictly "reel to reel," with no capstan! That is, spool to spool. It seems to me that the principle was borrowed from the sewing ma chine; the very fine steel wire was wound on a fairly wide, deeply flanged take-up spool via an oscillating guide that moved it from side to side and thereby, supposedly, kept the winding even and flat inside the spool. It did indeed, for several minutes at a time, when nothing else went wrong. The wire simply slid through a grooved magnetic "head" from the playing-out spool to the take-up spool.

As for the speed, it was constantly changing, never the same from beginning to end of the miles of wire on one spool. Sloppy, to say the least. In spite of the oscillating guide, humps and bumps and overlaps built up inside the spool, making for horrendous wavers and flutters in recording-and creating a second set of the same on playback.

I instantly discovered that this machine was totally useless for any kind of mu sic. What disillusion! My very first magnetic recording of a piano, played by my own fingers, came out like a distant flock of bleating sheep. Voice recordings were scarcely better, a confident spoken statement coming out like an announcer experiencing a nervous breakdown.

And then there was the vast frequency range, which must have extended from about 200 Hz far upwards to may be 2,000 cycles, as we called it. No bass, no treble. Just a fine, distant middle range. And lots of hiss.

Now, the original Webcor was a respectable and reputable firm, though it departed a good while back. (The newer Webcor hi-fi equipment merely took over the old name; it's no relation.) I should say that these faults were common enough in other audio areas of the time, and I expect that the too--hasty urge to get on the market, at a time when designers and parts and supplies were still war-limited, might have had a lot to do with the performance I am describing. Remember the Kaiser and Frazer cars? Same era.

There was worse-a lot worse. As you might guess, the wire speed past the record/playback head varied enormously, depending on the size of the two rolls, like the ribbon spools in an elderly typewriter. Still, about a day after my first dismal try, I began to think further. How about this wonderful new idea of editing? Could you actually take out bits of sound you didn't want? Well, yes, you could. After a fashion.

The wire was remarkably fine-that was its major problem. Also very hard and springy. In fact, it was almost impossible to handle, off the taut spool.

Nevertheless, you could, if you carefully held the ends, snip out the offending portion with a pair of scissors-and tie the wire back together in a knot! Outlandish sort of editing, made worse by the springiness, which meant you had to make a very tight knot if it were to hold, instead of springing apart after the first play.

I tried it. It worked, more or less, though the little bumps of the edit knots would hump up the wire on the spool, thus making for pitch inaccuracy. This was the first edit in my history, and one of the first in audio history too, I'm willing to bet.

Woe betide you, though, if your fingers slipped on that fine wire and the ends sprang free. Instant chaos. Both spools, full of steel springiness, would immediately unroll and loosen up. The pitch relationship would be utterly destroyed in seconds, from one end to the other. Can you envision the trauma when that happened? At that age, I was more persistent than I am today. You could call it obstinacy, and you would be right. I had paid my money; the machine was sup posed to work. So I kept on coming back for more. I tried splice after splice, with bow knots, bosun's knots, and what-not; I recorded off the air and off my shellac records; I brought in friends to babble sweet nothings at the mike. And then I found another dire fault. The magnetic head recorded mainly on one side of the wire. When, during rewind and replay, the wire inevitably twisted on its own axis, the volume went up and down disconcertingly. All in all, not a very practical recorder.

The final straw came, as I said, after about two weeks of intermittent torture.

I figured maybe I could join two "takes" from different spools of wire if the amount of wire on each was about the same, and thus recorded at the same speed. I just wanted to see if I could do something useful and new with the machine. (I was edging to wards magnetic tape editing, though I did not know it.) And so came the end.

One day, near nervous exhaustion after hours of frustrating effort, one loose spool went flying out of my hands, spewing behind it hundreds of almost invisible coils of springy wire. In grabbing for that one, I dislodged another from a nearby shelf, and it dropped, shedding more shiny coils. In an instant the room was filled with the stuff.

I tried, obstinately, to wind that wire back on the spools, all those hundreds of feet, if not miles. I worked for an hour at least. Then suddenly I had had enough. With a burst of profanity, I flailed my arms around until I had gathered a huge armful of tangled wire and made straight for the nearest waste basket. Next day, that machine was gone. I forget what I did with it.

(by: EDWARD TATNALL CANBY; adapted from Audio magazine, Jan. 1988)

= = = =