Manufacturer's Specifications:

Type: Pre-polarized condenser.

Directional Characteristics: First-order cardioid.

Frequency Response: On axis, 40 Hz to 20 kHz, + 1, -2 dB at 12 in. (30 cm).

Nominal Sensitivity: 10 mV/Pa (-40 dB re: 1 V/Pa), individually calibrated, with integral 20-dB attenuator.

Maximum Sound Pressure Level: 158 dB peak SPL, before clipping.

THD: Less than 0.5% at 110 dB peak SPL.

Equivalent Noise Level: 19 dBA re: 20 µPa.

Output Impedance: 180 ohms.

Phase Response Matching: ± 15°, 100 Hz to 20 kHz, for any two microphones.

Power Requirements: 48 V phantom, per DIN 45-596.

Connector Type and Polarity: Three-pin XLR type; pin 2 positive with increasing sound pressure.

Supplied Accessories: 16-ft. (5 meter) cable, windscreen, locking stand mount, and mahogany box.

Optional Accessories: Shock mount and clip-on stand mount.

Dimensions: 3/4 in. diameter x 6 1/8 in. long (1.9 cm x 17.5 cm).

Weight: 5.9 oz. (165 grams). Price: $1,497 each.

Company Address: 185 Forest St., Marlborough, Mass. 01752, USA.

The Model 4011 cardioid and the similar Model 4012 are welcome additions to the line of Brüel & Kjaer studio microphones, whose omnidirectional models were reviewed in the November 1984 issue. Application of the latter has been somewhat limited by their omnidirectional characteristics. The cardioid pattern of the new mikes opens up the possibility of using B & K mikes for coincident stereo microphone arrays, such as X-Y or ORTF. Cardioids can also reduce acoustic "leakage" in multi-track recording and will permit increased gain before feedback in live concerts where sound reinforcement is used. The inherent proximity effect of a pressure-gradient mike (such as a cardioid or figure eight) may be used to give "warmth" to vocals and to cancel background noise.

The Model 4011, which I tested, is intended for use with mixers that can provide 48-V phantom power. The Model 4012 is intended for use with the Model 2812 power supply, which provides 130 V to the microphone, giving it a 10-dB higher input-level capability.

The 2812 is a two-channel unit with line-level outputs that can be connected directly to a recorder for improved S/N. Both the cardioid microphones and the power supply are transformerless, which can reduce low-frequency distortion. In my 1984 test of the omnidirectional mikes, transformers were needed at the recorder in order to reduce hum and noise when the 2812 was used with long output lines. The 4011, however, yielded good S/N when used with long house lines.

The coincident arrays mentioned above, often used for classical recording, are not the prime application for which the 4011 and 4012 were intended. B & K feels they are better suited to pickup of individual instruments in multitrack "pop" applications or as accent mikes in classical music recording. The reason is that these mikes are designed to have flat response to a point source at 12 inches (30 cm). The response at 4 feet and beyond is rolled off at low frequencies, due to proximity effect. All pressure-gradient microphones exhibit this effect, and the curves are published in books.

In his April 1989 "Behind the Scenes" column, Bert Whyte states: "Some B & K mikes respond as low as 2 Hz! In contrast, most cardioid mikes have a low-frequency response that rolls off rather steeply below 40 Hz." Whyte indicates that the omni mike is the best choice for recording low bass. (He was discussing high-grade condenser mikes for recording applications; some omni mikes, such as dynamic models made for speech use, also have rolled-off bass.) My files of test data show that Whyte was correct: The response of the B & K omnidirectional studio microphones was ruler flat down to as low as I could measure, and many cardioids exhibited a roll-off below 50 Hz (at infinite distances). Two cardioids I have tested had exceptional bass, the AKG C-422 stereo mike (whose mono version is the C414) and the Sennheiser MKH 40 (reviewed in the January 1988 issue). With both of these mikes, response at 30 Hz was-3 dB at infinite distances and +7 dB at 12 inches.

However, there is a trade-off, as these microphones have larger diaphragms than the 4011 and 4012. Thus, their gain in bass response is at the expense of the off-axis high frequency response. According to B & K, the problem with extending the bass in a small-diaphragm mike is that the cardioid pattern becomes non-uniform at higher frequencies. The company is researching this and may eventually offer a version with extended bass for classical recording.

My review of the remarkable Nakamichi CM-700 series of condenser microphones (September 1978) indicated that the response of the Nakamichi cardioid was flat at 12 inches, similar to the 4011's, yet I made good orchestral recordings with it. When I tried a bass equalizer, as shown in the review, room rumble was excessive.

The B & K press release states that they spent 10 years developing the 4011 and the 4012, and that each has a nickel-based diaphragm similar to that of the company's measurement microphones. The microphone's matte black housing is machined out of solid brass. The integral 20-dB attenuator is selected by a switch recessed behind the output connector. The locking stand mount is a clever design that holds the mike securely. A quick-release clip mount is also available.

Measurements

The 4011 has no accessory power supply, so I opted for battery operation using my UTC HA-108X line transformer, which is very well shielded and offers a 200/200-ohm impedance match for isolation. I found a nominal 9-V battery at Radio Shack (Cat. No. 23-583), which actually delivers 9.6 V. The magic of this is that five of these batteries add up to exactly 48 V. My test methodology eliminated the effects of the transformer from the resulting data: In the impedance test, the effective series resistance was measured by substituting a resistor of known value for the mike and then subtracting this value from the measured data. In the response and noise tests, a calibrating voltage was inserted in a balanced mode between microphone and transformer. By this means, the open-circuit voltage of the microphone was measured. For descriptions of my impedance and frequency response test schemes and the sound source used for response tests, see "The Compleat Microphone Evaluation" (April 1977; update, September 1978). Two microphones were furnished by B & K from their demo stock, each in its own hardwood box. There would have been no need for B & K to hand-pick a matched pair; thanks to tight production tolerances, all these mikes are, for all practical purposes, alike. Each 4011 is calibrated at the factory and comes with a computerized frequency response curve made in an anechoic chamber. As I said in the 1984 review, the accuracy of calibration at the B & K factory is comparable to that at our National Bureau of Standards.

Since B & K provides individual data only for the axial frequency response of each mike, my other measurements could only be compared to the nominal data in the manual.

Just as I began testing, I encountered a vexing problem: The cable furnished had Neutrik connectors on it that fit one mike snugly and were extremely tight in the other. Then I tried lab cables with Switchcraft plugs; they latched up tightly and had to be removed with pliers. B & K had indicated that the inside diameter of each mike housing was machined to fit at least three brands of connectors, but that they had still encountered problems because the various manufacturers of XLR-type connectors do not make them alike. I hope B & K will opt to open up the barrel and settle for a more sloppy fit. A subsequent tour of local electronics stores turned up connectors from Neutrik, Switchcraft, Cannon, and an unmarked Cannon look alike (the latter two from Radio Shack)--not all of which mated with each other. This appears to be a very serious problem that calls for attention from a standards organization.

I noticed another mechanical problem when I tried mounting a 4011 on a stand using the furnished locking adaptor. It held the mike securely, but its hinge was too loose and could not be tightened to give the desired degree of friction.

I did not run all tests on both mikes. 1 selected the mike with the easier fitting connector for all tests. The other mike was tested only for axial response and sensitivity, plus cross-checks on selected aspects of performance. Both mikes were used in the listening tests.

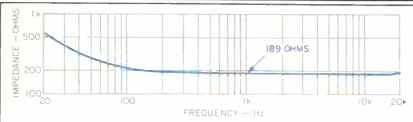

Fig. 1--Impedance vs. frequency.

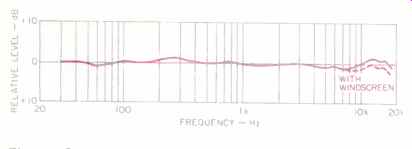

Fig. 2--On-axis frequency response at 12 inches (30 cm) from source; 0 dB

equals-40 dBV/Pa.

Fig. 3--Comparison of on axis frequency response of two B & K 4011s,

at 12 inches (30 cm) from source.

The impedance curve (Fig. 1) shows that the measured value of 189 ohms at 1 kHz was close enough to the rated 180 ohms. The low-frequency rise indicates a series capacitor, perhaps to block d.c. in this transformerless mike. If the mike were connected to a matched load (200 ohms), a serious loss of bass response would result. I suggest using a minimum input impedance of 5 kilohms to avoid this loss of low-end response.

The axial response curve (Fig. 2) shows, for all practical purposes, a ruler-flat response from 30 Hz to 18 kHz. (I measured response at 12 inches from the source, as did the factory.) I was pleased to find that the resulting curve was very close to the factory calibration chart. The 1-dB wiggles below 1 kHz in Fig. 2 are not on the factory curve and may by systematic errors caused by the acoustics in my room, which is not quite anechoic.

This may be the first time my measurements at low frequencies on a pressure-gradient mike have agreed with the manufacturer's data. The usual measurement problem has been related to the sound source. I use a 2-inch-diameter aluminum dome set flush in an 8-inch aluminum sphere, specially made by the late Al Witchey of RCA more than 30 years ago. (I have tracked its calibration for 25 years, and there has been negligible change.) Various manufacturers of microphones I've reviewed in the past have used commercial speakers, typically 8-inch, for microphone testing.

Tests at distances closer than twice the source diameter do not yield the correct response. With the 2-inch source, accurate tests can be made at 4 inches or more, but with an 8-inch speaker, proximity effects are all but unmeasurable.

The small source probably could be duplicated from the drawings I have, but to date, no company has expressed interest.

B & K has avoided the complexities of building a small sound source by using a small commercial speaker and an FFT analyzer. The speaker is the "David" Model 2001 made by Visonik in West Germany. They use the tweeter only, energized by repetitive pulses that are converted to frequency response curves by an FFT analyzer. This analyzer can store curves from the mike under test as well those of a standard mike and can then print out the difference curve.

How can they test bass response with a tweeter? The answer seems to be, "with difficulty." The printout is at spot frequencies, spaced a constant number of hertz apart.

Thus, the curve is continuous at high frequencies but choppy at low frequencies. My old-fashioned test with a swept sine wave and a proper sound source may be more accurate at low frequencies, albeit more time consuming. In this regard, it is interesting to note that at high frequencies, there are no differences between the data I obtained and B & K's, but at low frequencies, my curve is flat whereas theirs is down by 1 to 1.5 dB. For microphone testing, the FFT method seems better than the TDS method, as the latter is limited by average room size to frequencies above about 200 Hz. However, the TDS method (as used by B & K for experimental microphone tests using a microphone as the source) yields the energy-time response of the mike under test, which is of interest.

Figure 2 also shows the effect of the windscreen on frequency response; it is negligible.

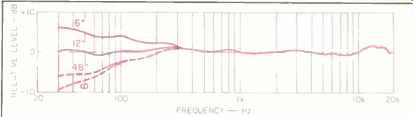

Fig. 4--Frequency response as a function of distance from source.

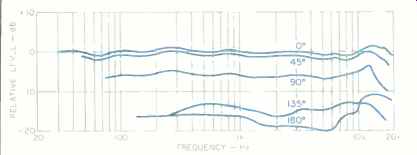

Fig. 5--Frequency response vs. angle.

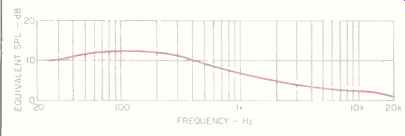

Fig. 6--Third-octave noise spectrum; 0 dB equals 20 µPa.

The axial near-field frequency response of two 4011 units is compared in Fig. 3; one of the units is even more ruler flat than the other.

Figure 4 shows how the bass response varies with distance. The solid curves indicate measured data at 6 and 12 inches. The dashed curves show the calculated responses at 48 inches and infinity; these calculations are fairly accurate due to the physics involved. The dashed curves suggest the sound one would obtain when recording outdoors; in real rooms, actual bass pickup may vary with source geometry and room acoustics.

Figure 5 shows directional characteristics of the 4011.

The responses out to 90° are essentially identical up to 12 kHz. The responses at 135° and 180° are down about 15 dB, which is sufficient, and if my room was more perfect, the 180° curve would probably show "cancellation" of 20 dB or more, as in the manual. The peak in the 180° response at high frequencies is attributable to the mike but is not a significant defect. These results indicate performance which is about as perfect as can be attained in a 3/4-inch mike.

Overall A-weighted noise level was 17.5 dB (1.5 dB lower than specified), and the unweighted noise level was 24.0 dB. Figure 6 shows the noise spectrum; the curve is very smooth, with no bad features such as hum pickup or increasing levels at very low frequencies. The noise level is comparable to that of the lower noise version of the B & K omni mike and should not be noticeable in a quiet studio.

==================

IN THE STUDIO

If product presentation equaled product recognition, then Brüel & Kjaer would surely be the world's most well-known microphone manufacturer. These people border on the compulsive when it comes to microphone development and construction; even the mike carrying cases are finely tooled. Open up the shipping box, and you find a smooth hardwood case with top-quality hinges and a sure-closing clasp. Inside is a molded, hard-plastic carrying form so perfectly cut the mike fits exactly. You almost have to flip the case over and shake it for the mike to fall out.

B & K sent two Model 4011s for review. My principal testing site was Servisound, an audio production facility located on West 45th Street in New York City. With the help of friend, engineer, and overall advertising dude Joseph Casalino, I put the 4011s to the test. I wanted to see how they fared in different settings within a commercial studio. These mikes, by their design, should be flexible--capable of properly reproducing many sound sources. I started off with voice, a basic narration at first, and later, at another facility, male vocal. In each case, the B & K mikes were unbelievably accurate and extremely sensitive--so sensitive they were prone to "popping" when hit with breath blasts (such as when "p" was spoken or sung). Three quick solutions remedied this undesirable effect: Moving the mike further from the speaker/singer, placing the mike so that the singer was off axis, or placing a commercially available windscreen, such as a Popper Stopper, between the artist and the mike.

(The more common sock-type screens hurt more than help, because they block out too much of the sound source.) I went on to miking bass and snare drums, cymbals, acoustic piano, and electric guitar with the 4011s. The snare drum produced such a hot signal that console attenuation was employed. The result was not as punchy as I would have liked for heavy rock music, but when reduced levels--such as those for pop and jazz--were used, the mike once again came alive.

Placement becomes very critical when miking a snare drum with the 4011; the mike does not have to be placed so close to the drumhead.

B & K offers a -20 dB attenuation switch on the 4011. However, it is positioned in the base of the mike, in the center of the three XLR pins. This is inconvenient for studio and stage work, as it's annoying to have to take the mike cable off and insert a tiny screwdriver into the base simply to kick the attenuator into action. A switch on the housing would be less time consuming.

The kick drum test was interesting because the 4011 doesn't have a large diaphragm. When that much air is being moved, manufacturers generally go to a mike with a larger diaphragm. This was the only case in which I had to employ creative equalization to get a real rock kick drum, and I was still impressed with the result. One "drawback": The 4011 is so sensitive, you will have to make sure that you limit extraneous noises--such as bass drum pedal squeaks--or you'll have those on tape. You'll probably start hearing sounds you didn't know were there.

In fact, the mike itself adds practically no noise to the circuit, even when the console preamps are cranked way up for recording quiet signals.

In all miking situations, the B & K 4011 performed extraordinarily--especially when compared to microphones which have become known as industry standards. The final sound was more realistic, more detailed, and simply more accurate.

What I heard in the studio was more faithfully transferred to the control room, and thus to the tape.

There are two major reasons, however, why individuals and professional studios might be reluctant to accept the B & K line of microphones.

One is they are very expensive; each 4011 retails for $1,497, and even many top-quality studio mikes cost several hundred dollars less. The price of the B & K does include a case and a mike stand holder, however. (The holder is very good and secures the mike solidly. Other manufacturers should look to duplicate or secure a licensing agreement for this design.) The second reason lies in the performance. The 4011 is so accurate that many engineers, producers, and musicians may feel what they hear is too strident, too sterile. Because of their frequency response, many microphones impart a particular sound quality to a voice or instrument. They give a sound source a warm or mellow quality. This is what many in the recording industry have come to know as the "right" sound. It is not.

Any time a mike or mixing console alters the tonal quality of a voice or instrument, it becomes something other than the passive sound conduit it was meant to be. What you hear in the studio, from the instrument, is what you should hear in the control room, through the monitor speakers.

B & K will have to get its communications guns out and try to reeducate many people in the industry. This will not be an easy task in a business steeped in imitation.

The B & K 4011 is an excellent product. You'll be hard-pressed to find a better microphone. It is certainly capable of handling a multitude of miking tasks. Still, despite its ability to handle the wicked levels produced by snare and bass drums, its rightful place seems to be miking other acoustic instruments--piano, guitar, percussion--and vocals. I imagine string sections, brass, and reeds would also sound true to life. Unfortunately, these instruments were not available to me during my evaluation.

Studios in the habit of purchasing numerous mikes, each manufactured for specific purposes, may well be spending more than it might take to purchase a few of the more versatile B & K mikes. Others who should look into B & K microphones are individuals who do minimal stereo miking of jazz or classical music, and electronic musicians. MIDI players ordinarily don't need more than two or three mikes in their arsenal-for vocals, acoustic guitar, and sampling-so those mikes may as well be the best available.

--Hector G. La Torre

===================

Use and Listening Tests

To get a feel for the sound of the 4011, I first conducted a crude listening test using my voice, some noise from an air conditioner, and a new CD of the Empire Brass played on my outdoor test source. (The latter is an Altec Lansing 755E 8-inch speaker in a rigid fiberglass sphere; see the September 1978 issue.) I had just heard the Empire Brass in concert, so I thought I remembered how they really sounded. The best reference mike on hand was a Nakamichi CM 700 cardioid. It is an audiophile mike, but its frequency response is very similar to the 4011's. The mikes sounded very similar when picking up on-axis speech or music.

Speech at 3 to 6 inches sounded the same on both; the proximity effects were the same. Speech from any direction sounded the same on both mikes. After adding the air conditioner noise to the room, I found that the speech-to noise ratio of each mike was the same. This indicated that the directional patterns were similar. Each mike was very wind sensitive, but this was reduced by the windscreens on each. With the CD, each mike sounded the same when picking up on-axis sound. With sound sources 90° off axis, the B & K sounded the same as it had at 0°, but the Nakamichi sounded high-pitched or "tinny." The 4011 had essentially no sensitivity to magnetic hum, having no transformer, but the Nakamichi had high hum output.

The more formal listening test was conducted in the 900 seat sanctuary of the United Methodist Church in Haddonfield, N.J., where I am the sound person. The ceiling is 40 feet high, and an AKG C-422 stereo microphone is suspended about 17 feet above the floor, aimed downward and forward to the chancel area. The capsules are set for an included angle of 90° because their patterns are normally set for figure eight (bidirectional); this forms a Blumlein array, which I find works best in this auditorium. The 4011s were mounted on a Shure S-15 stand using an M-27M mounting and were positioned as high as possible, about 2 to 3 feet below the AKG. They were aimed downward and forward, with the 120° included angle that is correct for cardioids. The AKG was set for cardioid, but it was not practical to increase the included angle between its capsules. The 4011s were connected, via about 250 feet of cables in conduit, to the Soundcraft M200B mixing board in the balcony. The board has eight inputs and four main outputs. The stereo outputs were connected to a Sony SLHF500 Beta Hi-Fi VCR. The church has an active program of concerts, and this year we did the Brahms "Requiem" with 50 members of the Philadelphia Orchestra and 150 voices. It would not have been appropriate to agitate the musicians by setting up microphones that they hadn't seen at rehearsals, so I waited for a concert that did not involve professionals. It was a lively affair put on by the young people's choir and included 50 voices, pipe organ, piano, percussion, electric guitars, and synthesizer. Thus, the sound was more "pop" than classical. They performed modern sacred music plus some classical and popular tunes. The vocal mikes (Beyerdynamic M500 ribbons and Audix dynamics) used six channels, so I had only two left to play with. Therefore, I used the AKG for the first half of the concert and the B & Ks for the second half. The problem was that some instruments were moved and others were changed during the intermission.

I played the tape in my listening studio, which has been described in previous reviews. Briefly, I have a pair of modified Altec Lansing 604C speakers in sealed, stuffed boxes of more than 10 cubic feet apiece; they are equalized and driven by 100 watts per channel. This system can produce 120 dB SPL, and since the ambient noise is 30 dB SPL or less, I can use the rated 90-dB dynamic range of the Beta Hi-Fi recorder. Unfortunately, the acoustic S/N in the church is much poorer, due to the organ blower, the blower of the ventilation system, people, and outdoor traffic.

I have a curtain hiding the speakers in my listening room, which is helpful in localization of recorded sound sources. I found that the sources recorded by the AKG were contained within a smaller angle than those recorded by the 4011s because of the difference in microphone included angles.

The sonic images from the 4011s extended from wall to wall, so I concluded that 120° is correct for X-Y cardioids in this auditorium. I fixed the problem by moving my chair forward when listening to the AKG. I found that the AKG and B & K mikes sounded alike on choral music, with the B & K sounding perhaps a shade better on piano overtones. The 4011s were outstanding in reproducing percussion from the far right. The sound of the cymbals was perhaps the best I've heard from any mike--not bright and brassy as with a "gimmick" microphone, just natural, clear, and crisp. The lowest bass in the concert was from the guitar, not exactly earthquake sound, but the 4011s did not seem to lack in bass. The AKG has a linear frequency response at high frequencies, as do the B & K mikes, but it has wiggles due to reflection from the cage surrounding the capsules. These have minimal effect on sound quality, because unlike resonant dips or peaks caused by defects in the diaphragm, they do not spoil the transient response.

However, this comparison with a microphone having very smooth response revealed the effects of the wiggles in the AKG's response.

I consider the AKG C-422 a super mike and, as the B & Ks seem to be just a shade better, concluded that they too must be in the super category. Since a pair of 4011s costs roughly the same as the C-422, I judge the 4011s to be a good value. The lesson I learned from this is that a 3/4-inch diameter cardioid can offer an optimum combination of acoustical performance and dynamic range.

--Jon R. Sank

(Source: Audio magazine, Jan. 1990)

= = = =

Also see: Brüel & Kjaer Type 4003 and Type 4007 Studio Condenser Microphones (Nov. 1984)