German maestro Wilhelm Furtwangler finally returned to New York this season in spirit if not in body after an unanticipated absence of seven decades. The arrival on Broadway of the play Taking Sides, dramatizing the conductor’s interrogation by an Allied tribunal after World War II, could be viewed as the final chapter in the long process of his “de-Nazification.” During a life that was marked from the outset with enormous promise, Furtwangler endured intense artistic and political controversy. Remarkably, four decades after his death there is more interest in him and his recordings than ever before, with several small labels devoting most of their energies to reissuing tapes of his live concerts. And, as the enormous success of Taking Sides attests, the truth about his heroic efforts to aid the victims of Nazi brutality has finally been recognized by the music-loving public.

When the tall, athletic conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic made his American premiere in 1924, it was clear to all present that a musical phenomenon had arrived—a Kapellmeister to rival New York’s adopted Toscanini and Philadelphia’s Stokowski. The honey moon was short-lived, however. Within a few years the maestro’s limited social skills and indifference to political niceties had alienated society patrons and en raged the most important music critics, and he left the US in 1927 with no immediate return in sight. At that rime, no one would have guessed that the estrangement would be permanent. But no one could have foreseen the madness that would envelop this century, and the symbolic role an unwilling and unprepared Furtwangler would play in it.

As music director of the Berlin Philharmonic for over three decades, from 1922 until his death in 1954, Furtwangler’s life and ant were to be the last fading glimpses of the world of Romanticism. Born in 1886, he regarded Beethoven and Brahms as spiritual intimates (his grandfather was a friend of Brahms’s), and German culture was his birthright. With Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, the conductor was forced to decide whether he should remain in Germany to defend his music and his orchestra against the Nazi agenda, or renounce his native land (as the Italian Toscanini was to do) and become a symbol of political resistance.

Furtwangler chose to stay. This decision caused him much personal grief, and still serves as a lightning rod for many listeners who can’t reconcile the humanity of his music-making with his decision to work with the most in humane of regimes. ‘Whatever his reasons, he was undoubtedly naïve, believing, for example, that his efforts to defend Jewish musicians could help stave off the inevitable catastrophe. His decision to remain, however, may have been based on his deep devotion to his orchestra as well as his conviction that German art must be kept alive especially in the country’s darkest hour. Had he left Germany, the Vienna Philharmonic— which Hider had ordered disbanded and of which Furtwangler was also principal conductor—would have ceased to exist. There’s also evidence that members of the Berlin Philharmonic would have eventually wound up in uniform on the Eastern front. The maestro fought tirelessly to assist all those who came to him, and, as Dan Gillis documents in his 1970 biography, Furtwangler in America, he ultimately saved the lives of dozens of Jewish refugees.

Most of this was revealed at the post war tribunal, but many were unimpressed with the facts. Bruno Walter wrote: “You carried your tide and position during [ Nazi regime]... of what significance is your assistance in the isolated cases of a few Jews?” Envy also played a part in the vehemence of his detractors. As Sam Shirakawa points out in his 1992 biography of Furtwangler, The Devil’s Music Master, many of those who were most unforgiving — such as Thomas Mann and Otto Klemperer— did not leave Germany voluntarily in protest, but were forced out. Several years after the war, both the Chicago Symphony and the Metropolitan Opera tried to engage the conductor as music director, but protests and threats of boycotts prevented him from entering America again during his lifetime.

The pressure cooker into which Furtwangler was thrust had a definite effect on his artistry. He was already a penetrating and dramatic interpreter, but his performances during the war achieved an unprecedented intensity— the reflection of a soul and a country in crisis. After the war, his art broadened and became more reflective, with results that were often equally profound.

“Reported on” vs “Re-created”

The “Golden Age” of conductors during the first half of this century was marked by a style of interpretation very different from what we encounter today. Artists often treated scores with a familiarity that modem musicians would find unseemly. Toscanini’s approach was considered by many an antidote to the personalized interpretations of the era: He felt that scores were to be adhered to “literally,” with the predominant personality being that of the composer rather than the Interpreter.

Furtwangler, however, believed that the literal reading of a score made it seem “reported on” rather than “re-created.” While he rigorously analyzed the texts left to him by the great composers, once on stage he was seized by a musical vision that transcended the rigid rhythms and static tempos used to notate the loftiest ideas. The printed page was, for Furtwangler, a compromise forced on composers, and he was more interested in the “spirit” of the work.

The contrasts were striking. While Toscanini often adhered to one strict tempo throughout a given movement, Furtwangler would vary the tempo according to each new mood of a piece, leading his listeners through the whole gamut of human emotions. While he was not alone in this “subjective” approach (indeed, Stokowski’s conducting was more colorful, and Mengelberg’s often had more personality), Furtwangler’s insight into the “serious” Germanic repertoire was unsurpassed. While the man suffered harsh judgments during his lifetime, many have since come to consider him, as Kirsten Flagstad succinctly put it, the “greatest conductor of all time.”

His often frenzied inspiration was captured on tape in live performances both during and after World War II. Furtwangler’s studio recordings, on the other hand, often failed to take flight, inhibited by the sterile atmosphere of the studio as well as by the interruptions of recording engineers. The wide array of recordings to choose from, often primitive in sound and variable in performance quality, has made it difficult to get an adequate introduction to Furtwangler’s art.

There has never been a better time, however, to become acquainted. Labels such as Music & Arts are attempting to make virtually every Furtwangler con cert tape in existence available to the public, and a new French label, TAHRA, is unearthing original master tapes that present certain Furtwangler performances in stunningly vivid sound—the perfect starting point for those frightened off by low-fidelity “historical” recordings. With an ear toward those recordings with the most realistic sound, what follows are recommendations for the finest of Furtwangler’s recorded legacy.

The Last Romantic: The young maestro at his pensive best.

Bach and Mozart

Furtwangler’s “Romantic” approach was most controversial in Baroque and early Classical music. He used frill, modern orchestras playing with an abundance of expression that is often derided today as “sentimental.” His 1954 performance of Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion (EMI 5 65509 2), however, stands with Mengelberg’s as a compelling argument for understanding Bach in the interpreter’s world rather than trying to re-create Bach’s world. The tempos are measured and the tone solemn, but the frill power of the Passion text is brought to life.

Furtwangler’s full-blooded approach to Mozart may also take some getting used to, but he left sensational accounts of Symphonies 39 and 40 (DG 427 776- 2 and 427 773-2), and his Salzburg performances of the popular Mozart operas are enchanting, if a tad too serious. The element of wit is, in fact, the one virtue noticeably lacking in Furtwangler’s con du his Mozart rarely has the gentle irony that enlivens Beecham’s interpretation Still, his 1954 Don Giovanni (EMI 7 63 860 2) is a magnificent drama, aided b good sound and a great Don Giovanni (Cesare Siepi) and Donna Elvira ( Schwarzkopf). His 1951 reading of the The Magic Flute (EMI CDMC 65356) with the Vienna Phil harmonic and State Opera Chorus can also be highly recommended. In general, while Furtwangler’s Mozart is fascinating and moving, it is just one approach, and not necessarily the final word about the music — unlike his often definitive Beethoven.

Beethoven

Finding an attractive EMI boxed set of Furtwangler conducting Beethoven might seem a natural way for a collector to get started, but it would be a mistake. Furtwangler gave himself to the inspiration of the moment, and the incessant interruptions of studio recording could render the performance stillborn. While some of the EMI Beethoven recordings are successful, the cumulative effect is of relentless dragging. It is much better to start with individual releases of the live performance tapes.

There are fine Furtwangler performances of the Symphonies 1 1952, Music & Arts, CD-711) and 2 1948, EMI 763 6062), but with the revolutionary Symphony 3 his approach is visionary. No account on record compares, however, with Furtwangler’s war time “Eroica” (1944, Preiser 90251), per formed with the Vienna Philharmonic.

The limited sonics cannot veil a performance of incomparable heroism in the outer movements and profound tragedy in the Marcia funebre. The best version of Symphony 4 (1953, Nuova Era 013.6310) is also with Vienna. With Symphony 5 we have an embarrassment of riches a total of 11 performances to choose from. The wartime Fifth (1943, DG 427 775- 2) is a masterpiece, but even it does not match the intensity of the much-better—sounding performance from the first concert of the Berlin Philharmonic after the war (1947), in which Furtwangler seems to release all the frustration of the war years in one utterance —a powerful and unique document. The second half of this concert also contained what is in some respects his most moving “Pastoral” Symphony, and it is paired with the Fifth on Music & Arts CD-789. This same program was repeated near the end of Furtwangler’s life (1954), and while the performances are more res trained, they are among his greatest. This later concert has been released by TAHRA (Furt 1008-1011), along with the best post-war “Eroica” (1952), using the original broadcast tapes. Aside from some graininess and a touch of distortion, it is hard to believe that these are “historical” recordings. Those familiar with previous releases of these performances will be shocked by the vivid instrumental detail and wide dynamics. The TAHRA set should be one of the first choices of collectors.

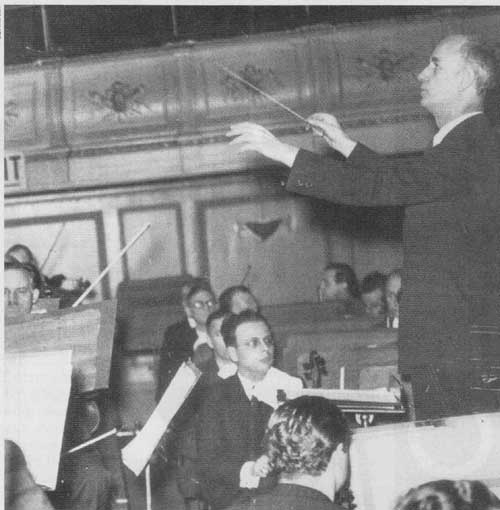

p203---Before the storm: Furtwangler rehearses the Berlin Philharmonic in

1938.

The EMI recording of Symphony 7 (1950, CDH 7 69803 2) has much better sound than the fiery wartime performance (1943, DG 427 775-2), and Symphony 8 is also available in good sound (1953, DG 415 6662/427 4012). As fine as these readings are, however, it is with Symphony 9 that Furtwangler again scales the summits. The classic performance from the reopening of the Bayreuth Festival after the war (1951, EMI CDH 7 69081 2) has stiff competition in the recent release of a live 1954 performance in Lucerne with the Philharmonia Orchestra (TAHRA Furt 1003). The latter performance is more polished and exciting, while there is a smoldering intensity and great profundity in 1951. The Bayreuth performance is in decent sound, but the new release by TAHRA of the Lucerne con cert tips the scales in its favor. The glory of Beethoven’s chorus of brotherhood can be heard with deep bass and beautiful texture, all molded by Furtwangler into an otherworldly experience.

Other Beethoven highlights include the Corolian Overture (1943, DG 427 780-2 and 427 773-2), Furtwangler’s last live performance of Fidelio (1953, Fonit Cetra CDC 12), and the “Emperor” Concerto with Edwin Fischer as soloist (1951, EMI 7 61005 2). Perhaps the most fascinating of Furtwangler’s concerto collaborations is also with Edwin Fischer, in Brahms’s Piano Concerto 2 (1942, DG 427 778-2 and 427 773-2). This familiar work takes on entirely new dimensions with these like-minded artists, each in his prime.

The Brahms First Symphony is another pinnacle of the maestro’s output. Al though the most famous performance in Berlin (1952) has languished out of print, an even more intense performance with the North German Radio Orchestra from Hamburg has been issued by TAHRA (1951, Furt 1001), and the sonics are a revelation. Chords of granite underpinned by deep, solid bass make the opening of this performance irresistible, and the ardent Romanticism Furtwangler brings to the work forces the listener to reconsider viewing Brahms as a late “Classicist.” This release is a must for any collection — unless one is interested in the complete Brahms cycle, in which case the new Music & Arts release of all four symphonies on three discs (CD-941) will be a bargain. It includes a similarly fine remastering of the same Hamburg First as well as the most riveting Furtwangler performances of Symphonies 2 (1945), 3 (1954), and 4 (1943), and the Haydn Variations (1951). The Brahms cycle on EMI (ZDHC 65513) has less successful performances of Symphonies 1 and 4, but 2 (1952) and 3 (1949) are lovely alternatives to the swashbuckling Music & Arts choices, emphasizing the “autumnal” quality we usually associate with Brahms.

Wilhelm and Richard

It was Wagner who first articulated the need for tempo modulation in conducting while Furtwangler’s dramatic ebb and flow continue to be controversial in the symphonies of Beethoven and Brahms, it is undeniably natural in the operas of Wagner. In Tristan und Isolde (EMI CDS 7 47322 8) the tempos unfold effortlessly from the reverie of the Prelude to the ecstatic Liebestod (sung by Kirsten Flagstad), engulfing the listener in a sense of rap ture. This 1952 Tristan is a revelation, and in many respects the conductor’s most successful studio recording. As John Ardoin argues in his 1994 study of the maestro’s recordings, The Furtwangler Record, the studio atmosphere probably even enhanced the recording, allowing Furtwangler to focus on the ethereal and symbolic in the score, rather than the human drama on stage.

Unfortunately, Furtwangler did not live to complete his Der Ring des Nibelungen cycle in the studio, leaving us only Die Walküre (1954, EMI CHS 7 63045 2), warmly recorded by EMI and beautifully played by the Vienna Phil harmonic. For the complete cycle we must turn to two less than optimal choices: a live 1950 Ring from La Scala (Music & Arts CD-914) featuring Flagstad as Brunnhilde, and a 1953 concert version from Rome (EMI CZS 7 67123 2), conceived as a test run for the pro posed studio cycle. While both sets have their strengths and weaknesses, the sound on the La Scala set is markedly inferior to the more carefully taped Rome performances (available at mid-price). At some point the options will dramatically increase with the release of two complete cycles from Covent Garden, the second of which (from 1938) features the pairing of Flagstad with Lauritz Melchior. Even then, and despite the many glories of the Italian Rings, we will be left without the promise of the EMI Walküre: a Furtwangler Ring traversal with one of Europe’s greatest orchestras.

The master Brucknerian

The Symphonies of Bruckner are per haps the perfect mate to Furtwangler’s conducting style. (They were truly kindred spirits — Furtwangler’s own essays in composition, including three symphonies, have the same expansiveness and sense of the ineffable as Bruckner’s.) Unfortunately, the available performances are few, and the sonics are usually too weak to convey the true majesty of the playing. The listener is almost always faced with compromises.

Of two performances of the Fourth Symphony with the Vienna, recorded a week apart, the first (October22, 1951) is available in good sound (DG 415 664-2 and 427 402-2), but the more exciting performance (October 29, Priceless D 14228) is thin and flat-sounding. Like wise, Symphony 5 with Berlin during the war (1942, DG 427 774-2 and 427 773-2) is more compelling than the much-better—sounding Viennese performance (1952, Hunt CDWFE 360). Furtwangler’s tremendous reading of Symphony 6 (1943, Music & Arts) is missing the first movement. Music & Arts has released great performances of Symphonies 7 (1951, CD-598) and 8 (1949, CD-624), but there are better- sounding taped performances of each (a Seventh from 1949 is soon to be released on EMI), and an Eighth from March 14, 1949 that has yet to see the light of day.

No such hard choices are required, however, with Furtwangler’s sole taping of Symphony 9, a wrenching performance from 1944 (Music & Arts CD- 730). The sound is far from ideal, but the level of commitment from conductor and orchestra is likely never to be equaled.

There are, of course, many other riches in the Furtwangler discography. Some classic interpretations, such as the Schubert Ninth Symphony (1953, TAHRA Furt 1008-1011), are available in several incarnations in good mono sound, the best-sounding of which is available in the same TAHRA set that includes the Beethoven Symphonies 3, 5, and 6 (TAHRA Furt 1008-1011). Other recordings, however, like the Tchaikovsky “Pathetique” (1938, Biddulph WHL 006- 007), are truly “historical,” challenging the listener to imagine the lush orchestral set ting rather than really hear it.

Fortunately for both the serious collector and the merely curious, there are now many editions that will provide both the emotional involvement of Furtwangler’s conducting and the sensual enjoyment of orchestral sonorities. In particular, the impressive-sounding TAHRA releases of his Brahms First and Beethoven Ninth symphonies will be an excellent introduction to this noble but controversial musical soul. The new listener may soon find himself “taking sides.”