ELVIS PRESLEY--It just wouldn't have been the same without him, ASHELEY R. and KERRIN L. GRIFFITH

A brief music-history lesson, by Asheley R. and Kerrin L. Griffith

Some two decades ago in the Year 1956 there took place a Revolution in American Music.

The upheaval had been preceded by signs, portents, harbingers and even precursors, but hardly anyone today doubts that the man who really started it all was Elvis Presley

Elvis---did you ever hear of anyone else named "Elvis"?--was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1935.

The rural South tends still to cherish names that have gone out of fashion elsewhere-Vernon, Gladys-and others that are unique, exotic originals Vester, Cletis, Elvis.

Elvis' farm-worker father Vernon ran off at seventeen with Gladys Smith, twenty-one, a sewing-machine opera tor in a garment factory. They "ran" five miles, got married, and returned to Tupelo. A few years later Vernon's brother Vester married Gladys' sister Cletis, giving Elvis a double aunt and a double uncle-simple generational arithmetic makes this a not unlikely event in small communities. Father Vernon was fair, mother Gladys dark.

Both worked hard and attended the First Assembly of God church. When Gladys became pregnant, the couple rented their first home: two rooms on a cement-block foundation straddling the mud when it rained and puddles when, as it often did, it flooded. Identical twins were born to the Presleys there on January 8, 1935. Elvis Aaron was born first; Jesse Garon was born dead.

Elvis Presley grew up during the Depression and World War II. He was blonde, polite, and apparently not greatly memorable to anyone but his kin. At some point during those years, Elvis recalls, he asked for a bicycle; his parents bought him a guitar because it was cheaper. He grew up listening to country music and blues and singing white gospel in church. When he was thirteen, the family-his world moved to Memphis. They were poor, cooking on a hotplate in one room, later moving into a federally subsidized housing project.

Elvis sang a bit in high school, but nobody seems really to have noticed.

He liked shop class and R.O.T.C., wore unusually long (for the time) hair with sideburns and tight pink and black clothes. He liked to go to carnivals and movies. He had grease in his hair and pimples on his cheeks. He was, in the sartorial sense at least, a kind of home made, farm-club "hood"-except that he adored his indulgent parents, especially his mother. He held factory and movie-ushering jobs, he had girl friends, and he punched a few people for various unimportant reasons. In 1954 he had been out of high school for a year, he was driving a truck for $42 a week, and he was interested in music, cars, and girls, in no particular order.

THERE should be some kind of small fanfare right here to mark the entrance of Sam Phillips of Sun Records; he got Scotty Moore and Bill Black to provide back-up for Elvis at his recording studio after Elvis had done a solo demo there as a birthday present for his mother. The result was the singer's first officially released record: That's Al right (Mama) on one side and Blue Moon of Kentucky on the other. It was a local success in Memphis. The second effort (Good Rockin' Tonight and I Don't Care If the Sun Don't Shine) did less well, and the third (Milkcow Blues Boogie/You're a Heartbreaker) simply flopped. So did a performance at Nashville's Grand Ole Opry.

Another, and considerably louder, fanfare, then, for the entry of Colonel Tom Parker, a middle-aged ex-carnival barker and public relations veteran (a typical stroke: he once hired extras from the Wizard of Oz cast to parade through Los Angeles as "The Elvis Presley Midget Fan Club"). Colonel Parker got Elvis' career in his-you name it-grasp, pocket, jurisdiction, guidance just as the Big Money started to roll. Or maybe the Big Money start ed to roll only because of the Colonel; nobody will ever know. Either way, by 1956, the year Elvis Presley attained his legal majority, the Colonel had al ready sold his Sun contract to RCA and signed him to appear on network TV with Steve Allen, the Dorsey brothers ... and Ed Sullivan. Almost overnight Elvis the Pelvis became a national sensation with hordes of young (mostly female) worshipers and as many older detractors. In the next two years over 28,000,000 Elvis Presley records were sold. How did it happen? What did it all mean? Confluences are what made it hap pen. It was not merely a case of the right person, the right- place, and the right time, but a whole series of right people, places, and times. There was, first of all, Sam Phillips, who specialized in molding singers without much prior performance experience (some of his later finds were Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, and Jerry Lee Lewis). Phillips supplied Elvis with guitarist Scotty Moore, an accomplished musician who strongly influenced the young singer's development.

Counting Elvis, that's three "right" people so far, and it's only 1954 in Memphis. Add now the Colonel, the enigmatic huckster with an uncanny ability to recognize marketable talent and a whiz at the actual marketing as well (for example, he sold young Presley's contract to RCA for what was then the unbelievably high figure of

$40,000, and he got Ed Sullivan to pay triple the largest amount he had ever paid anybody for an appearance on his show). All of which is a roundabout way of saying that Sam Phillips, Scotty Moore, and Colonel Parker were critical elements in the development of Elvis Presley and therefore in the rise of rock-and-roll.

Parker and Phillips were, like Elvis, "hicks" by Northern, urban standards, but both had music-business experience and knew what they were doing.

Except that they couldn't have, really, for Elvis just wasn't Elvis yet. His voice was good, but not great. He wasn't movie-star gorgeous, just sexy.

He wasn't a musical prodigy either, no ace guitarist, accomplished actor, or even-especially-any kind of song writer. Nonetheless, all the imperfect pieces somehow fitted together and added up to a unique musical style, a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

But Elvis was not invented; the strange thing is that it all had to happen just as it did. Once the diverse musical and cultural elements had come together in Elvis, once he was exposed to Phillips, Moore, and Parker, the whole thing meshed, and rock-and-roll was in evitable. Elvis had to be a poor white d fundamentalist Southerner, and some thing of a hood. He had to be poor, and he had to have grown up listening, on radio and in the flesh, to the necessary kinds of music-especially Mississippi hillbilly, Memphis blues, and gospel.

He had to be white, or superstardom in benighted 1956 would have been impossible, but he also had to be close enough to black performers that he could absorb their techniques. He needed to have acquired the juvenile-delinquent machismo of the mid-Fifties and he needed the experience of tent –

show evangelism to teach him how to arouse an audience to frenzy and even hysteria. He had to be handled by people experienced in the already subtle ...

... arts of c-&-w and r-&-b, people skilled in the mechanics of popularization.

And he had them: Phillips had specialized in supervising little-known black vocalists, and the Colonel, even before Elvis came along, had packaged and promoted a number of country-music figures.

Yet that's not all. Pop music, always more of a grab bag than the narrow disciplines of country and rhythm-and blues, habitually borrowed freely from both, and as a result Elvis became a star in all three categories with a synthesis that required the coinage of the unlikely word "rockabilly." What counted most was the simple power, the authority with which Elvis joined previously separate characteristics of music and style. He wasn't the first to do it, and perhaps he wasn't even the best, but the product he cooked up and served was the one that sold, the one that was physically conspicuous, aural ly arresting, and satisfying, as they say, in spades.

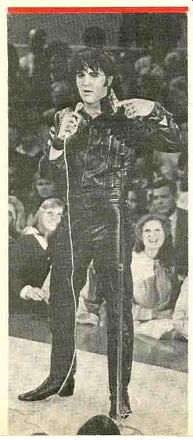

WHAT Elvis did twenty years ago was to set off a revolution, no less, and its reverberations are still being felt to day musically, socially, and culturally. Rock-and-roll is that revolution's name. It had been a long time in com ing, but it was born in 1956 and personified in Elvis. This is not to deny the very real importance of Little Rich ard, Chuck Berry, or any of the other vanguard artists; they were great, but in the light of Elvis' success they were merely candles. Heartbreak Hotel, Presley's first RCA single, was re leased in January of 1956. By that same June Elvis' sales accounted for fully half of RCA's pop product.

For those who can't, won't, or don't remember the attendant avalanche of publicity, comparisons with two other phenomena are apt. First, the Beatles: they too kidnapped all the adolescents in the land, piping them away to the tune of television exposure, movies, and saturating record marketing. Second, think of the Kennedy assassination and particularly of the funeral. It is of course absurd to consider the two events as being parallel in any historically significant way, or of having a like emotional weight. What is comparable is the overall impact and scope of the media events themselves, each-the death of a President, the birth of rock and-roll-a kind of watershed marking a distinct shift in the nation's political attitudes, in its cultural sensibilities. In both cases, we simply haven't been the same since.

Just why rock-and-roll should suddenly emerge from the lips-and loins-of Elvis Presley is a question that takes us far deeper than the rutted roads of Tupelo or the sound studios of Memphis. Ripeness, as King Lear had it, is all. In 1956 the music-or, more accurately, several overlapping mu sics-were primed for integration. The youthful audience was just as ripe, al ready strong enough to make it possible for Maybelline and Rock Around the Clock to infiltrate the Patti Page-Land of the adult pop charts. And the industry was ripe too, technically and bureaucratically, for new kinds of music and new ways of selling it-more sophisticated studios, more up-and-coming independent labels, the switchover from fragile 78's to casual 45's and al most-rugged LP's. Even the media power was relatively new-don't for get, it wasn't until the middle Fifties that practically everyone had TV, and transistor radios were only about to be come as ubiquitous as the six-pack is today. Above all, however, Elvis was ripe, physically, vocally, professionally. The juices were flowing.

SOME believe that his Sun records are the best Elvis ever cut. Others use those same records to gravely demonstrate obvious to possible influences: Jimmie Rodgers, Otis Spann, Muddy Waters, Roy Acuff, Arthur Crudup, and, yes, even Dean Martin. Such cataloging is fascinating-and ultimately unrewarding. Elvis took from a lot of places, and the taking was probably as often deliberate as it was unconscious.

What emerged, however, was Elvis, not undigested scraps. When you listen to the sources, it is impossible not to wonder at what the King (the nickname his fans gave him as opposed to the Pelvis, a mere media tag of the Fifties) accomplished. What comparisons illustrate is mostly what he didn't borrow, for the range of what he did incorporate is enormous: bluegrass, cocktail piano, hiccups, yodels, panting, echo chambers that sound like aural halls of mirrors, wailing saxophones, cloying background vocals, hoof-beats, spoken asides. The songs themselves vary from candid black blues to whiny white ballads. Who else ever moved so easily between raunchiness and bathos? Who else ever wanted to? Elvis made Sun records for only six teen months. That's Alright (Mama), the first, is also perhaps the best. It's a blues, and for once he is singing slightly against the back-up band rather than wallowing in its mush. The voice is young-sounding, resonant, full of sap; Bill Black and Scotty Moore are perfect without making any virtuoso intrusions. The words become ambiguous, the singer both pleading and reassuring ("that's alright, mama, anyway you do") so that it sometimes sounds like "anyway you do it" and other times like "anyway you'll do." His hurry seems to come from desire, not lack of control.

Blue Moon of Kentucky and I Don't Care If the Sun Don't Shine are of interest primarily for the funny country voices (and the rhythms) he uses. An altogether different story is Good Rockin' Tonight, a real rockabilly tune that set the vocal pattern Elvis was to use (and overuse) so many times: a high introductory phrase followed by a low response. It also has full stops, another trick he came to rely on (as in Treat Me Nice). Like That's Alright, it is full of declarations and questions, announcements and desires. And the phrasing really is good, the line "To night she'll know I'm a mighty, mighty man" runs headlong into "I heard the news [breath] there'll be good rockin' tonight." Most of the other Sun sides are period relics: You're Right, I'm Left, She's Gone prefigures the Johnny Cash style and introduces drummer D. J. Fontanna to the trio-not always a boon; one version of I Love You Because has a spoken interlude prophetic of perfectly dreadful things to come. By and large, however, the remaining things Elvis did at Sun are of only moderate interest, with the possible exception of Mystery Train-it's all promise, wonderful but frustrating.

MOST of his old RCA singles, alas, don't hold up well either; they have a vintage sound but little real stature. Heartbreak Hotel is curious and not un pleasant, and Hound Dog isn't all that great any more-but both can still pack quite a wallop if you're old enough to remember their first time around. The best, probably, are Don't Be Cruel and All Shook Up. The former makes Elvis' formula clear: get the girls to lis ten, sound ardent, and then beseech.

It's all mood; the words of Don't Be Cruel are relatively so unimportant that when he sings "Let's walk to the preacher" it doesn't sound so much like "wa . . . to . . . prea . . ." as it does "one . . two . . . three." The lyrics are, if anything, improved by such destruction; they are not, in any event, where the message lies.

He had better lyrics to work with in All Shook Up, so he makes them all comprehensible, and even his interject ed "unhs" are perfect-not too loud, as they can be, not too forced. And for once he shows all his personalities in a single verse: first the black rhythm man ("She toucha mah han' an' what a thrill ah got"), and then, without a pause, the country boy ("Ah'm proud to say that she's mah ... buttercup") and the horny city slick ("Unh. I'm all shook up").

A few of the ballads manage to show off Elvis' voice. Love Me Tender is the most memorable as well as the most instructive about his technique. The M mouth takes over suggestively, fascinatingly, here for the bodily twitches that would accompany a rocker: on the key words "dear," "tender," and especially "fulfill," the jaw moves pro vocatively-you can hear it.

Finally, there is his all-time great production number, Jailhouse Rock, which shows rock-and-roll already full grown, already stylized, mannered, and insular, settling for volume and spectacle rather than innovation or "departures" of any sort.

How was Elvis consistently able to unite opposing worlds, white and black, country and urban? Well, like any good American athlete, he showed prudence on the opposition's turf and daring on his own. He expressed both, without hypocrisy, because his style was two styles. He was respectful, modest, humble, charitable, and wide eyed. He was also outrageous, flashy, cocksure, hungry, and heavy-lidded.

He performed both ways and he lived both ways, and since he was never aware of any contradictions between the two, he never projected any complications. Ambiguity, yes; complexity, no. He sang sentimental ballads and hymns with a straight face and hard-edged fast songs with simpering sneers and grinding thrusts.

The lyrics of his early songs reflect this duality. The ballads were sweet and direct and oozed abject devotion; as a result they don't sound false to day, just syrupy. But the rock songs have different words, nonsense sylla a bles, innuendos, and usually some innocent unifying element-a dog, say, or shoes. A lot of puddle-deep non sense has been written about the Fifties "fixation" on clothes and emblems, Blue Suede Shoes often being used as a typical example. But that song, as Elvis sings it, isn't about a pair of shoes. It is a list, a series of invitations to assault:

do violence to me, honey. You can do this, you can do that. This too, umm hmm. But no, honey, there's one thing you can't touch-my blue suede shoes. . . .

Elvis may never have understood what he was singing, nor the kids what they were hearing. It was almost as if all those duck's ass, ponytail (now there are some symbols for you!) heads wanted something, but they didn't want to identify it too exactly. They just wanted it dirty and they wanted it fast; Elvis delivered--ambiguously.

Unsympathetic older folks thought Elvis' sensuality was physical; they found him visually crude and lascivious, which he was. But that was only part of it. Elvis could deliver his bump and grind even over the radio, indicating that his power really lay in the mu sic and what he did with it.

IT would be surprising if a performer as popular and as durable as Elvis had not inspired a host of out-and-out imitators and more subtle borrowers-and he has, not the least of them being such latter-day pop saints as Bob Dylan and the Beatles. Although practically every garage band in Christendom tithes (spiritually of course) to the King, his influence on Bob and the Mop Tops is perhaps the most clearly documented, not only in living memory but in the rock press, which' has always been preoccupied with "roots." Dylan's debt to Elvis is alternately acknowledged and denied in the best "I'll--go--your--way--and--call--it-mine" tradition. According to Anthony Scaduto's biography, Elvis was Bobby Zimmerman's idol/ideal in 195g; by 1960 Bob Dylan was "somewhat disdainful of Elvis and the Blue Suede Shoes stuff.- In 1961 (the Woody Guthrie period) Bob claimed to have played session piano with Elvis; the following year Dylan reported that John Hammond had predicted he'd be "bigger than Presley!" The Beatles' Love Me Do hit the British Charts in 1963, and rock's star rose again. The Fab Four made their first appearance some time later on the Sullivan Show, and there was John Lennon, pumping his thin legs, curling his thinner lips, and wailing through Twist and Shout. According to Hunter Davies, the Beatles' original goal was to be bigger than the songwriting team of Goffin and King, but by the time they were scuffling, leather-jacketed, through the cellars of Hamburg their ambitions were loftier: they too wanted to be "bigger than Presley," the daddy of them all. Theft is flattery: on "Rubber Soul," the Christmas album of 1965, Lennon stole directly (he admit ted it only years later) from the Sun session tune Baby Let's Play House.

A new rock star of Elvis' magnitude has yet to appear in the Seventies, but almost all who have attained success during his reign credit his influence.

Songs associated originally with him have been recorded by artists as dispa rate as Joe Cocker, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and Bryan Ferry. Alvin Lee, who named his band. Ten Years After because he formed it ten years after Elvis appeared, blames the end of his performing career on his Woodstock rendition of Goin' Home, a pastiche of various bits from Blue Suede Shoes and Baby Let's Play House. According to Lee; when kids who had never seen Elvis saw Alvin do Elvis, that was all they wanted to see-Alvin Lee as Elvis P. End of Ten Years After, ten years after. Further, Elvis achieved such legendary status that imitators began "doing" him on the cocktail-lounge circuit the way they did Judy Garland-and Elvis didn't even have to die! He just became, for a period, relatively inactive (thanks to Army duty) on the entertainment front.

Through it all, however, Elvis has remained more essentially "American" than almost anyone (or any thing) around in this Bicentennial year. Mom, for instance, has left the kitchen and gone back to school, Apple Pie is made by a factory that calls itself Sara Lee, the Girl Next Door is pregnant and un married, and the Flag now adorns alarm clocks and beer cans. Presley, however, has changed hardly at all.

Oh, he's put on a little weight, and he's gotten (rather quietly) divorced. But, for the rest, he has lived a real-life Ho ratio Alger story. He is religious, he adored his mother, and he served two years in his country's service cheerfully. He doesn't smoke or drink. He is a stupendous commercial success, makes tons of money, and pays his in come taxes fully without dodges, loop holes, shelters, or complaints. He con tributes to charity and gives generously to friends.

MUSICALLY, he offers something for all but the most resolute of culture snobs. You may not care for the hymns and ballads he is given to singing, but millions of others do. And for those who don't there are the old rockabilly numbers he still performs and occasionally even new rockers that work-1972's Burning Love, for exam ple, or his current success For the Heart. And although it may be stretching the point to say that he was the cause of certain cultural changes, it is not too much to say that he symbolized them, some of them profoundly important. He spearheaded a cultural movement that broke barriers, and though the breakdown of racism in commercial music comes most immediately to mind, that is but a part of it. Elvis-and rock-and-roll-heralded major demo graphic changes that have deeply affected how this country lives and how it sees itself. It wasn't just that country-and-western and rhythm-and blues flowed together; rural and urban populations have had their visions of themselves and each other radically altered, there is greater communication between them, less insularity, less tension and bigotry. If all that seems to be a bit too much to lay at the door of a popular music, just try-to imagine those changes taking place without the pulsating undercurrent of that powerful music. And then try to imagine that music without Elvis.

-----

Asheley and Kerrin Griffith are sisters and rock-and-roll fans. Their ambitions, in no particular order, are to (1) finish their PhD's and (2) become Miss Subways.

Also see:

CHOOSING SIDES, IRVING KOLODIN

AUDIO BASICS--The New London Cassettes