EQUIPMENT TEST REPORTS--Hirsch -Houck Laboratory test results on the: Sansui TU-9900 AMIFM stereo tuner, Yeaple Stereopillow "nearphones," Kenwood KR-9600 AM/FM stereo receiver, and JBL L166 speaker system.

By Hirsch-Houck Laboratories---------------

Sansui TU-9900 AM/FM Stereo Tuner

THE Sansui TU-9900 AM/FM stereo tuner is part of that company's "professional" series of audio components, and it has the all-black finish that seems to be a styling trend just now. It is large as tuners go: 18 1/2 inches wide, 12 1/2 inches deep, and about 6 3/8 inches high; it weighs about 21 pounds.

Most of the front panel is devoted to a rectangular cut-out, the upper half of which contains the dial scales. Below them are two large meters; a switch that selects FM AUTO, FM MONO, or AM operation (also identified ored lights above the switch); and a large tuning knob. A fourth light serves as a stereo FM indicator.

To the left of the dial is a vertical row of seven square pushbuttons. The ANTENNA AT TENUATOR button reduces the signal reaching the tuner's input circuits by about 20 dB to prevent overload by very strong local trans missions. The BANDWIDTH switch provides WIDE and NARROW positions. Set to NARROW, the TU-9900 is highly selective (it is rated to have better than 90 dB alternate-channel selectivity), with distortion ratings of 0.5 and 0.8 percent, respectively, in mono and stereo. In the WIDE mode, the distortion ratings are dramatically improved to 0.06 and 0.08 percent. Selectivity is reduced to 55 dB, which is adequate under most circumstances.

The NOISE CANCELER button engages a high-frequency blend circuit to reduce noise (and high-frequency channel separation) when receiving weak stereo signals. Below it is the interstation-noise MUTING switch. A CALIBRATION LEVEL button replaces the audio output of the tuner with a 400-Hz tone at a level of-10 dB relative to 100 percent modulation. The primary function of this signal is to set up the recording level of a tape deck in advance of recording an FM broadcast. And although not mentioned in the instruction manual, it can be used to set up the levels of an external Dolby decoder as well. Since "Dolby level" corresponds to 50 percent modulation or -6 dB, the calibration tone can be used to calibrate a Dolby unit's meters by setting the level to -4 dB.

The LOW PASS FILTER button switches in a multiplex filter that cuts off 19-kHz and higher frequencies that might affect the Dolby sys tem of a tape deck or possibly beat with the bias oscillator in some tape machines. When the filter is out of the circuit, the frequency response of the tuner extends well beyond the audio range. Finally, the METER SELECTOR connects the signal-strength meter (there is also a channel-center tuning meter) to read multipath distortion as an aid to orienting an antenna.

The remaining front-panel controls are the OUTPUT LEVEL knob and a power switch. In the rear of the tuner there are inputs for a 300-ohm and a coaxial 75-ohm FM antenna plus a wire AM antenna. There is a hinged AM ferrite-rod antenna and two pairs of audio out puts. One carries the normal FM audio-output signal with the standard 75-microsecond de-emphasis characteristic, and the other pair (marked DOLBY FM) carries the same program with the 25-microsecond de-emphasis needed to make it compatible with an external Dolby decoder. The level from the normal outputs is controlled by the front-panel control (variable over a nominal range of 0 to 1 volt), while the DOLBY FM output is at a fixed level of 0.4 volt (at 100 percent modulation).

There are also outputs for connection to an external oscilloscope multipath indicator and a DETECTOR output ahead of the de-emphasis circuits for use with a possible future discrete four-channel FM decoder. The single a.c. out let is unswitched. Price: $450.

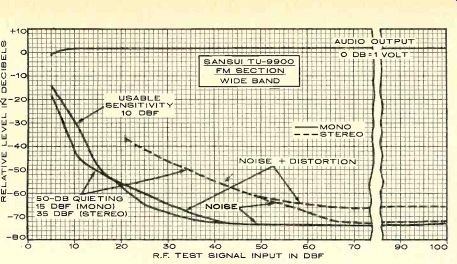

Laboratory Measurements. Because the' setting of the bandwidth switch affects many of the performance parameters of the TU-9900, we made most measurements using both switch positions.

In the wide-band mode, the IHF sensitivity was 10 dBf or 1.7 microvolts (uV) in mono. The 1.5-uV rated sensitivity of the TU-9900 is considered to be at the theoretical limits for an FM tuner, and our measured sensitivity is indicative of very high performance. In stereo, the usable sensitivity was set by the switching threshold at a 21-dBf (6-p,V) level.

More important is the 50-dB quieting sensi tivity, which was 15 dBf (3 µV) in mono with 0.35 percent total harmonic distortion (THD).

The stereo sensitivity was 35 dBf (30 uV), with 0.3 percent THD. Both of these figures represent very good tuner sensitivity. The sig nal-to-noise ratio (S/N) at a 65-dBf (1,000µV) input was one of the best we have measured: 74 dB in mono and 71.5 dB in stereo (at higher signal inputs the stereo S/N almost equaled the mono figure). The distortion at 65 dBf was also lower than we have ever measured on an FM tuner and well below the ratings of our signal generator -0.021 percent in mono and 0.052 percent in stereo. With out-of-phase (L- R) modulation of the signal generator (one of the conditions specified in the current IHF tuner standard), the stereo distortion was 0.32 percent at 100 Hz, 0.032 percent at 1,000 Hz, and 0.075 percent at 6,000 Hz.

The capture-ratio measurement (always difficult to make accurately or even repeatably) presented a challenge. Our reading was just under 1 dB, an outstanding figure. We could not measure the image rejection, which was better than the 100-dB range of our signal generator's output capability. The selectivity was close to the rated value, measuring 53.5 dB with alternate-channel (400 kHz) spacing and 5.7 dB with adjacent-channel (200 kHz) spacing. Both figures are fine for typical listening situations. The muting threshold was at 22 dBf (7 uV). The tuner's hum level was 70 dB below 100 percent modulation.

The frequency response with the LOW PASS FILTER disabled was almost perfectly flat, varying over a +0.2- to-0.6-dB range be tween 30 and 15,000 Hz. The filter had the expected effect on the frequency response, reducing the output by 0.4 dB at 12,000 Hz and by 2.5 dB at 15,000 Hz. In the process it dropped the 19-kHz pilot carrier leakage from -36 dB to an almost unmeasurable -85 dB.

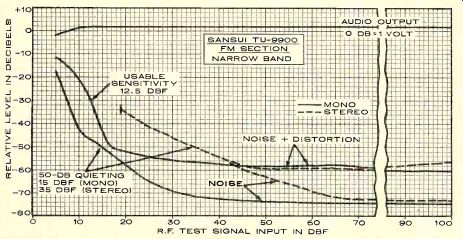

Finally, the stereo channel separation was an extraordinary 60 dB or more from 60 to 600 Hz, falling to 45 dB at 5,000 Hz, 40 dB at 10,000 Hz, and 34 dB at 15,000 Hz. The mid range separation was not only the greatest we have ever measured, but far exceeded the guaranteed rating of our Sound Technology 1000A FM signal generator. The S/N, stereo sensitivity, muting and stereo-switching thresholds, pilot-carrier leakage, hum, and frequency response were unchanged when we switched to the narrow-band i.f. bandwidth.

Mono sensitivity actually decreased slightly, to 12.5 dBf (2.3 uV). The 50-dB quieting sensitivity was unchanged, but the mono distortion at that input level increased slightly to 0.7 percent.

------- SANSUI TU-9900 FM SECTION WIDE BAND

--------- SANSUI TU-9900 FM SECTION NARROW BAND.

As expected, the THD increased slightly at the 65-dBf test level, although it was considerably better than rated and would be considered excellent in a tuner of any price. It measured 0.11 percent in stereo and 0.13 percent in mono. The stereo THD with out-of-phase (L- R) modulation also increased slightly to 0.36 percent at 100 Hz, 0.044 percent at 1,000 Hz, and 0.63 percent at 6,000 Hz.

With a reduced i.f. bandwidth comes a de graded capture ratio, and we measured it at 2.7 dB. On the other hand, alternate-channel selectivity became un-measurably high, exceeding 100 dB, and the adjacent-channel selectivity of 17 dB set a new record for our tuner measurements. Stereo channel separation was reduced to perfectly good, though no longer extraordinary, levels of 27 dB between 30 and 3,000 Hz and about 26 dB at frequencies above 4,000 Hz.

The output level from the Dolby FM terminals was a constant 0.42 volt at 100 percent modulation and a 25-microsecond de-emphasis characteristic. When we pressed the CALIBRATION LEVEL button, the output level of the tone from the tuner audio terminals was exactly as specified. The ANTENNA ATTENUATOR reduced the input signal by 22.7 dB. The muting action was ideal, with no transient noises or thumps. The flywheel tuning mechanism was smooth and friction-free. The FM dial scale was calibrated at 0.25-MHz intervals, and there was no detectable error throughout its range. The AM tuner had the usual restricted frequency response (it was, in fact, even narrower than most), with its out put being down 6 dB at 60 and 2,200 Hz.

Comment. In every respect except price, the Sansui TU-9900 qualifies as a true "super tuner" (which to us signifies a tuner whose key performance characteristics are far better than the norm for high-quality tuners). Possibly a few (very few) of its measurements have been surpassed by some other tuners, but most of those units were far more expensive-several times its price, in fact. Overall, we would consider the TU-9900 to rank with the other "state-of-the-art" FM tuners we have seen, and that is quite impressive in view of its comparatively modest price.

It was not easy to find things about the TU-9900 that one might quarrel with. There was one, however-the multipath indicator.

Like some others we have seen, this meter mode failed to respond to multipath levels revealed by an oscilloscope connected to the tuner's scope outputs and even by ear.

The -10-dB calibration signal proved to be a most useful feature for taping programs off the air. As Sansui suggests, it can be used to set the recording gain to 10 dB below the saturation level of the recorder, whatever that level might be. Then, one can record with assurance that the maximum dynamic range will be captured on tape without fear of distortion caused by unforeseen program peaks (FM stations in this country are well regulated in respect to their peak modulation levels, though the average levels may vary depending on the use of compressors and limiters).

Overall, we found the testing of the Sansui TU-9900 to be a challenging task, and we were left with a sense of surprise and pleasure at finding a product whose performance so far surpassed both its ratings and the expected norms for a unit of its price. And, as a fringe benefit, we now have a clearer idea of the inherent limitations of our very fine FM test equipment!

+++++++++++++++++++++++

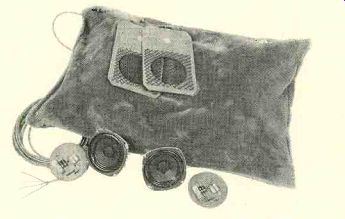

Yeaple Stereopillow "Nearphones"

THE Yeaple "Stereopillow" is a novel sound reproducer that combines many of the good features of both loudspeakers and headphones while eliminating some of the ma jor disadvantages of both.

As its name suggests, the Stereopillow is in the form of a pillow, 27 inches by 20 inches by 6 inches deep. Inside it are two high-quality 41/2-inch cone drivers (with 10-ounce magnets) mounted on small flat baffles and fully en cased in polyurethane foam. The pillow can be placed upright behind a chair or sofa or in a nearly horizontal position against the arm of a sofa for listening in a reclining position. The listener's head is partially surrounded by the pillow, so that the drivers are located about 2 inches from the ears.

In this near-field listening location, even the small, flat baffles permit an effective frequency response down to well below 50 Hz. Since the frequency response of the drivers falls off naturally below 400 Hz and above 10,000 Hz, a passive equalization network in the pillow boosts the lows and highs to achieve a relatively uniform response at the listener's ears.

Like loudspeakers, the Stereopillow pro vides a relatively stable stereo image which does not shift with small movements of the listener's head (although both the sound-pres sure level and the effective frequency response change rather rapidly if the ear is moved even a few inches from the drivers).

Room acoustics are completely out of the listening equation. Even while listening at sound-pressure levels exceeding 90 dB, the sound level elsewhere in the room drops off rapidly with distance, to 65 dB or less at spacings of 5 feet or more, and the sound usually cannot be heard at all in an adjoining room.

The system impedance of 24 ohms makes it possible to parallel several Stereopillows for simultaneous use without presenting the amplifier with a dangerously low load impedance. Only 2 volts is needed across the speak er terminals to produce a 95-dB sound-pres sure level at the listener's ear, which means that the Stereopillow can be driven by even the lowest-power amplifier or receiver (it must be connected to the speaker terminals, not the headphone output).

The Yeaple Stereopillow is available with a choice of several colored or patterned cloth covers that can be unzipped and removed for cleaning. The integral 30-foot cable enters the pillow at the upper right corner, and suggestions are given for dressing the cable and us- ing it to hold the pillow in place behind chair or sofa. Price: $79.95.

Laboratory Measurements. Evaluating the Yeaple Stereopillow required special test methods. The technique used by Yeaple to derive performance data (and by us to test the device) is to place a dummy head in a normal listening relationship to the pillow, with the latter supported in an upright position. A microphone is inserted between an "ear" of the dummy head and the surface of the pillow.

With a 10,000-Hz signal applied to each driver, the microphone is carefully adjusted for maximum reading and all subsequent measurements are made in that position.

Our measured data closely matched those obtained by Yeaple. With 2 volts applied, the frequency response was within ±2 dB from about 40 to 650 Hz, and it fell about 10 dB in a "shelved" characteristic to another flat region, where it was within ±2 dB from 850 to 3,000 Hz. There was a smaller depression (about 5 dB) in the 3,000 to 7,500 Hz band, where the output varied ±2 dB. Above this frequency the output rose about 8 dB and varied about ±1 dB from 7,500 to 13,000 Hz be fore dropping off at higher frequencies. At very low frequencies the response followed the manufacturer's claims, falling at 12 dB per octave below 50 Hz.

In its overall frequency response, the Stereopillow resembled a number of good-quality headphones we have measured. Like them, its effective response (as heard by the listener) is extremely dependent on the precise geo metric relationship between the two transducers and the listener's head. Specifically, a moderate shift of the ear relative to the surface of the pillow could make a considerable change in the response at very low and very high frequencies.

The sound-pressure level (SPL) measured in our test setup at a 2-volt drive level was about 110 dB in the bass and lower mid-range, 100 dB in the mid-range, and 95 to 105 dB in the upper mid-range and treble. In terms of conventional loudspeaker listening, this is very loud, although the sound was below nor mal background-music levels a few feet away.

-- Clad in one of its optional imitation-fur coverings, the Stereopillow

appears right at home propped up against the armrest of a sofa.

The distortion at 2.8 volts (equivalent to an amplifier output of 1 watt into an 8-ohm load) was in the 0.3 to 0.5 percent range from 1,000 Hz down to 100 Hz, and it rose gradually to 2.4 percent at 50 Hz and only 8.4 percent at 20 Hz. At a "10-watt" drive level (8.9 volts) the distortion remained under 2.5 percent down to 80 Hz, but it rose rapidly to 16 percent at 50 Hz.

The speaker impedance was about 24 ohms over most of the range from 150 to 2,000 Hz, falling to 15 ohms at 20,000 Hz and with a smooth rise to 50 ohms at the bass resonance of 57 Hz. Tone bursts were reproduced faith fully throughout the entire operating frequency range of the Stereopillow.

Comment. As is the case with headphones and speakers, frequency-response measurements do not adequately describe the sound of the Yeaple Stereopillow. Most of our evaluation, therefore, was done by listening to a variety of program material.

First of all, the Stereopillow does not sound exactly like either a speaker or a headphone.

With one's head firmly cradled in the pillow, the subjective frequency response resembles that of a good-quality speaker with somewhat subdued highs. The bass and middles are very powerful and smooth, although we never got the same sensation of low bass that is experienced with a speaker having a useful out put down to 40 Hz or so. We suspect that this is due to the lack of stimulation of the entire body surface by very low frequencies, a problem the Stereopillow shares with headphones, which often have an excellent measured low-bass response but do not sound as powerful in the bass as speakers with much less measured output.

Also as with headphones, the front-back localization of sound is a bit uncertain with the Stereopillow. This is helped considerably by listening in a reclining position, preferably with the eyes closed. Although the user is not confined to a rigidly fixed position, there is a rapid drop of listening volume if the head is moved more than an inch or two away from the pillow surface.

No matter how loudly one plays the Stereopillow, it is easy to hear someone speaking in the same room or a telephone ringing. This is a major advantage over most headphones and speakers (some, of course, might consider it a disadvantage). Naturally, other people in the same room will hear the program, albeit at a rather low level. It will not normally interfere with conversation, but we doubt that anyone would be able to listen at high volume to the Stereopillow in the same room with another person who is listening to a different program via speakers or watching a TV program.

Our only reservation regarding the Yeaple Stereopillow does not relate to its sound, which is very good-impressively so, at times. For upright listening, the need to support the Stereopillow in a vertical plane with its lower edge approximately at shoulder level limits its use to high-back furniture such as lounge chairs. However, there is no positioning difficulty when listening while lying down.

For those who can install the Stereopillow in one of its more effective positions, it offers an interesting and rather different approach to personal music listening at a price competitive with that of many medium-price headphones.

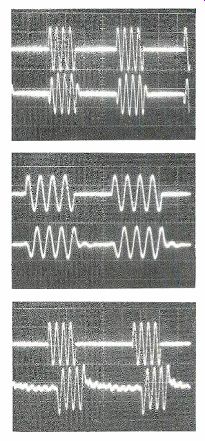

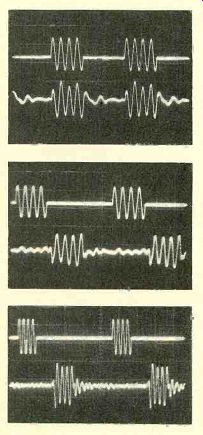

The Stereopillow's tone-burst response was quite

faithful, as shown in these oscilloscope photos made at (top to bottom)

50, 500, and 5,000 Hz.

++++++++++++++++

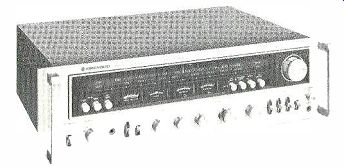

Kenwood KR-9600 AM/FM Stereo Receiver

KENWOOD'S new KR-9600, one of the select but steadily growing number of "super power" receivers, is a mighty unit by any standards. Its amplifiers are rated to deliver at least 160 watts per channel into 8-ohm loads, from 20 to 20,000 Hz, with 0.08 percent or less total harmonic distortion. Like some of Kenwood's integrated amplifiers, the KR-9600 uses an entirely separate power sup ply (including the power transformers) for each channel. This effectively eliminates what Kenwood calls "transient crosstalk distortion," which is described as a form of the intermodulation effect in one channel resulting from modulation of the common power-supply voltage by a powerful low-frequency signal in the other channel.

---------

The output stages, featuring fully complementary-symmetry transistors, are directly coupled to the speakers. A fast-acting relay protects both the output devices and the speakers from damage, as well as providing a time delay that eliminates thumps when turning the receiver on or off. At its input, the KR-9600 is unique in having separate preamplifiers for each of the two phono in puts. The PHONO 1 input, which has a 2.5-millivolt sensitivity and a 250-millivolt overload rating, uses an FET input; the PHONO 2 preamplifier, rated at 5 millivolts sensitivity with a 500-millivolt overload rating, uses a bi polar-transistor input.

The KR-9600's tone controls consist of knobs for bass, mid-range, and treble frequencies. They can be bypassed by a DEFEAT switch. The tone controls, like the volume control, are lightly but positively detented in steps. The receiver can control two tape decks, with front-panel switching for recording on either machine or dubbing from either one to the other, while monitoring the play back from either one or listening to the source signal.

A novel feature is the receiver's "sound injection" circuit, a variant of the microphone injection system found on some other receivers. Kenwood's system provides a fading and mixing action as the mrc LEVEL knob on the panel is rotated. It smoothly fades out the signal from the selected program source and inserts the signal from a microphone plugged into the front-panel jack. This injection action takes place only at the tape-recording outputs and does not appear in the receiver's audio outputs.

The FM tuner section of the receiver is of comparable quality, featuring two r.f. stages, a five-gang tuning capacitor, an eight-element linear-phase filter, and a phase-locked-loop multiplex demodulator. A switch on the front panel converts the de-emphasis time constant from 75 to 25 microseconds for use with an external Dolby adapter.

The two tuning meters read channel center and signal strength for FM (the latter is also the AM tuning indicator). A button on the front panel converts the signal-strength meter to read FM modulation strength, from 0 to 100 percent. In this mode, the meter has a fast response with little overshoot, and it can be used to set up recording levels on a tape deck for most effective use of the machine's dynamic range. Two other meters monitor the audio-output levels. Their logarithmic scales read from 0.1 to 200 watts, and a nearby but ton increases the meter sensitivity to cover a 0.01- to 3-watt range.

The Kenwood KR-9600, as might be expected, is large and heavy. Its satin-finish front panel is 22-Th inches wide and 6 3/8 inches high; the receiver extends about 16 1/2 inches behind the panel. All rear connectors are recessed and do not protrude beyond the case limits. A pair of rugged and attractive handles are supplied for mounting on the panel if de sired (the 53-pound weight of the receiver makes this very desirable), and the overall depth of the receiver including handles is 18 1/8 inches.

The front panel has pushbutton switches for low- and high-cut filters, 20-dB audio muting, power-meter range selection, FM meter mode, 25-microsecond de-emphasis, and FM muting. The large tuning knob, which operates a very smooth flywheel mechanism, is to the right of the dial. Across the bottom of the panel are knobs for the tone controls, volume (with a concentric ring for balance), the input selector (AM, FM, PHONO 1, PHONO 2, Aux), and speaker switching for three pairs of speakers or one combination of two pairs.

Lever switches control on/off, loudness (with two degrees of compensation), tone-control defeat, mode (MONO, STEREO, REVERSE), tape monitoring from either deck or the source, dubbing from either deck to the other, and the SOUND INJECTION circuit. There is also a headphone jack on the panel.

In the rear of the receiver are the many in put and output jacks, including preamplifier outputs and main-amplifier inputs, joined by removable jumper links. There are outputs for connection to an oscilloscope for multipath indication; the horizontal output is also intended to drive any future discrete four-channel FM decoder when and if it becomes available. There is a hinged AM ferrite-rod antenna, and terminals are provided for 75- and 300-ohm FM antennas as well as an AM wire antenna. Insulated spring clips are used for the speaker outputs, and there are DIN sockets as well as phono jacks for the tape-recorder connections. One of the three a.c. sockets is switched. Price: $750.

Laboratory Measurements. Following the standard preconditioning period, during which the receiver became only moderately warm, the amplifier outputs clipped at 189 watts into 8 ohms, 264 watts into 4 ohms, and 115.5 watts into 16 ohms (both channels driven at 1,000 Hz).

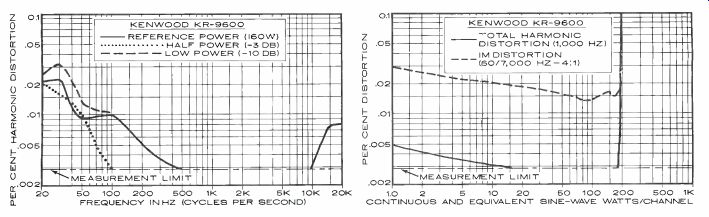

At most power levels and frequencies, the distortion was below our residual measurement level of about 0.003 percent. With a 1,000-Hz test signal, total harmonic distortion (THD) was less than 0.003 percent at all levels from 10 watts up to 180 watts, reaching 0.006 percent at 190 watts just before clipping occurred. The intermodulation distortion (IM) was between 0.015 and 0.03 percent from 1 watt to over 190 watts. It rose somewhat at very low power levels-about 0.2 percent at 16 milliwatts. At the rated power output and at levels of-3 and-10 dB, the THD was about 0.02 percent at 20 Hz and less than 0.003 percent from a couple of hundred Hz to 10,000 Hz, climbing to 0.008 percent at 20,000 Hz.

KENWOOD KR-9600 REFERENCE POWER (160W); TOTAL HARMONIC DISTORTION (1,000

HZ), IM DISTORTION

----- KENWOOD KR-9600 FM SECTION

An input of 0.038 volt at the auxiliary input or 0.6 millivolt at the phono input was needed to develop a reference power output of 10 watts. The noise level was extremely low, with respective unweighted S/N readings of 81 and 79 dB. The PHONO 1 input-overload point was a very high 290 millivolts. This was the more sensitive of the two inputs; the other (not checked) should have half the sensitivity and twice the overload capability.

The tone controls, as expected, could provide a wide variety of response curves. The loudness compensation was very mild with either of the two selectable characteristics (which boosted only the low frequencies), making it one of the few we have seen that does not impart an unnatural "bassy" quality to the sound. The filters had very gradual slopes of 6 dB per octave and removed too much of the program content for our taste.

Their -3-dB response frequencies were 200 and 3,600 Hz. The RIAA phono equalization was within ±1 dB from 20 to 20,000 Hz. It was affected negligibly by phono-cartridge inductance (less than 0.5 dB change up to 15,000 Hz, and only 0.5 to 1 dB at 20,000 Hz).

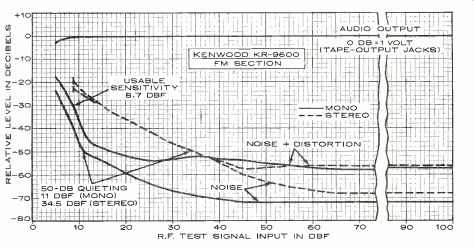

The FM tuner section had usable sensitivities of 8.7 dBf and 15 dBf in mono and stereo or 1.5 and 3 in microvolts (IN). The 50-dB quieting sensitivity was 11 dBf (2 µV) in mono with 0.75 percent THD, and 34.5 dBf (29.2 µV) in stereo with 0.3 percent THD. The ultimate SIN at 65 dBf (1,000 µV) was 71.5 dB in mono and 68 dB in stereo, and the respective distortion levels at that input were 0.13 and

0.34 percent (the latter being measured with out-of-phase-or left-minus-right-modulation in accordance with the new IHF tuner standard).

The capture ratio at 45 dBf (100 µV) was 1.4 dB, and AM rejection was 57 dB. The muting threshold was 8.7 dBf (1.5 µV), the same value as the stereo switching threshold.

Pilot carrier leakage was -73 dB and hum was -72 dB. The effectiveness of the tuner's circuits was demonstrated by its image rejection of 102 dB (just at our measurement limit) and by the alternate- and adjacent-channel selectivities of 91 and 9.5 dB.

The FM frequency response was flat within ±0.4 dB from 30 to 13,000 Hz and down 0.7 dB at 15,000 Hz. Stereo channel separation was exceptionally uniform: 36 to 37 dB across most of the audio range, and better than 33.5 dB from 45 to 15,000 Hz. The AM frequency response was down 6 dB at 35 and 5,400 Hz for a somewhat wider response range than most receiver AM tuners exhibit. All of these figures matched Kenwood's specifications within the bounds of instrument error.

Because of the extensive metering afforded by the KR-9600, we also checked the accuracy of the meter readings. The power-output meters (referenced to 8-ohm loads) read from 15 to 50 percent high at most levels, but this is probably adequate for their purpose. The FM deviation (modulation) meter was accurate at 100 percent, which is the most important point, but read high by about 10 to 20 percent at most smaller carrier deviations. This, too, is satisfactory for the intended use of the meter in setting up a tape recorder (especially since the maximum error was about 2 dB in the "safe" direction). The signal-strength meter gave useful readings at levels of a couple of microvolts and saturated at 370 microvolts, which gave a full-scale reading.

Comment. The Kenwood KR-9600 probably has more flexibility than most people will ever require, but such flexibility is expected of a premium-price product like this one. So far as we could determine, all of its many features worked exactly as claimed. In fact, it is such a smooth-handling and easy-to-use receiver that it can be operated, once one has overcome a sense of awe at its capabilities, as casually as any other.

The suppression of transients and other unwanted noises was so good that it was easy to forget that the amplifiers could deliver close to 200 watts per channel, which is sufficient to destroy many speakers. This attention to de tail is fortunate (and surely not accidental), since pops and thumps that are a mere annoyance with lesser receivers can be disastrous with a unit such as this. In this regard, we were especially appreciative of the ideal operation of the FM muting circuit, a potential Achilles' heel in high-power music systems.

It is apparent that Kenwood has carefully matched the performance of the tuner, con trol-amplifier, and power-amplifier sections, utilizing each to best advantage. The tuner's performance is just shy of matching that of some of the finest separate tuners, but it is well beyond what we have come to expect in a receiver. The control amplifier is one of the quietest we have seen, and it has enough input and operating flexibility for most people, though not as much as many separate preamplifiers. The power amplifier takes second place to none we have seen in the un der-200-watt-per-channel category. In fact, its distortion is literally unmeasurable without specially modified test equipment at almost any power level and frequency one will en counter in a home music system. If that is not perfection, it is certainly close to it.

Like other receivers in its power class, the Kenwood KR-9600 cannot be installed casually. It is simply too large and heavy to be stuffed into a piece of furniture (it must be adequately ventilated, since we found the temperature on the top of the cabinet to be nearly as high in normal use as during our tests). The handles on the panel are more than decorative, being the most practical way to lift or move the receiver.

When we come to the "bottom line" of value for the money, we must say that this is a very reasonably priced product for what it does (take a look at the prices of power amplifiers with comparable performance if you doubt this). If your speakers require a high-power amplifier (or can safely be used with one), the KR-9600 can give you top-quality sound in a single, handsome (albeit large) package at an affordable price.

++++++++++

JBL L166 Speaker System

THE JBL L166 is a compact, three-way speaker system whose 1.75-cubic-foot cabinet makes it one of the larger "bookshelf" systems, and it would appear to be at least as well suited to floor installation. The 12-inch woofer (with a 3-inch voice coil) operates in a ducted-port enclosure. There is a crossover at 1,000 Hz to a 5-inch mid-range cone driver that operates up to 6,000 Hz. High frequencies are radiated by a 1-inch dome tweeter fabricated of resin-impregnated linen with a vapor-deposited layer of aluminum.

The oiled walnut cabinet has a distinctively sculptured, acoustically transparent, foam plastic grille that covers the entire front of the speaker. Behind the grille are calibrated level adjustments for the mid-range and high-frequency drivers. Their center positions are chosen to provide a flat "anechoic" frequency response. The calibrations cover a range of ±3 dB around the flat setting (at the counter clockwise limit, each control completely silences its driver). Special twist-type binding posts are recessed into the rear of the cabinet. The foam front grilles are available in orange or in black.

The JBL L166 system is rated to handle up to 75 watts of continuous program material, and, like other JBL speakers, it is quite efficient. It has a nominal impedance rating of 8 ohms. Its polar dispersion is rated at greater than 150 degrees up to 20,000 Hz-an exceptionally broad coverage for conventional front-facing drivers. The cabinet is 23 1/2 inches high, 14 1/4 inches wide, and 13 inches deep; the system weighs about 50 pounds. Price: $399.

Laboratory Measurements. With its level controls set to "0," the averaged output of the JBL L166 measured in the reverberant field of the test room was very smooth and flat throughout the audio range. When combined with the bass output up to about 300 Hz (which was measured with close microphone spacing to simulate an anechoic measure ment), the total response varied only ±3 dB from 50 to 20,000 Hz

The port contributed to the total bass out put only at very low frequencies (below 30 Hz), and the low-frequency output dropped off very rapidly in the range below 50 Hz or so. Unlike some speakers whose output rolls off at the highest frequencies, the JBL L166 had a slightly rising output above 10,000 Hz to about +5 dB at 15,000 Hz. It should be noted that these measurements (except for the low bass) reflect the actual sound-pressure level measured in a normal listening room about 12 to 15 feet from the speakers, and therefore they are representative of what actually reaches the listener's ears in a "real world" environment.

The distortion was very low down to about 50 Hz, and surprisingly it did not change appreciably when the power input was raised from 1 watt to 10 watts (based on an $-ohm impedance). Below 50 Hz the distortion at 1 watt rose to about 6 percent at 30 Hz and more rapidly below that frequency. We also measured the distortion with the drive level adjusted to maintain a 90-dB sound-pressure level (SPL) at a distance of 1 meter from the speaker grille. Down to 50 Hz it was identical to the constant-level measurement, but it in creased more rapidly at lower frequencies as the drive was increased to compensate for the falling bass response. It measured 12.6 percent at 40 Hz and could not be measured be low that frequency.

The mid-range ("presence") control had a range of +2 to-5 dB between 1,000 and 6,000 Hz, while the high-frequency ("brilliance") control had a ±3-dB range above 2,000 Hz.

The speaker impedance reached a maximum of about 60 ohms at 58 Hz and low values of 6 to 7 ohms at 25 and 125 Hz. Over most of the audio range the impedance was not far from its nominal 8-ohm rating (or somewhat higher), but it fell to just under 5 ohms at 9,000 Hz. The tone-burst response of the L166 was good throughout its range.

As expected, the L166 proved to be a very efficient speaker. Driven by 1 watt of random noise in the octave centered at 1,000 Hz, it produced an SPL of 93.5 dB at a 1-meter distance. This is about 6 dB greater than that produced by a typical acoustic suspension speaker. Putting it another way, the L166 would require about one-fourth as much amplifier power for the same listening level as a typical bookshelf speaker system.

Comment. Having listened to the JBL L166 for some time before performing any tests, we were not in the least surprised by our findings. From the first, it was evident that this was an exceptionally smooth, uncolored speaker. It gave an impression of strong bass response as a result of the slight resonance rise at 67 Hz which affects the band of frequencies from 65 to 100 Hz or so. The very low bass (under 40 Hz) is down somewhat from the midrange level, but because of the speaker's excellent octave-to-octave frequency balance, most listeners would not be aware of any lack of very deep bass. The extreme highs are excellent indeed. They impart a sense of crispness and definition that is often lacking in otherwise good speakers. Because of the overall flatness of the speaker's response, one never feels that any particular portion of the spectrum dominates the others.

The dispersion, judged subjectively, was as good as was claimed-certainly at least as good as we have heard from any direct-radiator speaker system.

Having obtained confirmation of our initial hearing impressions through the response measurements, we expected the JBL L166 to do very well in our simulated live-vs.-record ed listening test. It did. On some of the selections, the JBL's sound could not be distinguished from that of the "live" reference. On others there was an indefinable difference too slight to be identified precisely. All in all, the L166 is one of the more accurate speakers we have evaluated in this way.

------ Tone-burst response of the JBL L166, shown here at (top to

bottom) 100, 4,000, and 7,000 Hz, was good throughout.

Anyone who has a stereotyped image of JBL as a manufacturer of "rock-sound" speakers will be surprised by an exposure to the sound of the L166; it is one of the smoothest, most listenable systems we have had the pleasure of using. It is also one of the most expensive "bookshelf" size speakers you can buy. If your budget can handle it, listen care fully to the L166; even if it is beyond your Means, its sound may guide you toward a less expensive speaker with some of the same fine sound qualities.

---------------

Also see:

NOISE DILEMMA--Is it possible to have full dynamic range without noise? DANIEL QUEEN

EQUIPMENT TEST REPORTS: Hirsch-Houck Laboratory test results on the: Audio Pulse Model One time-delay system, Avid 101 speaker system, Realistic SA-2000 integrated stereo amplifier, and Shure M24H stereo/quadraphonic phono cartridge, JULIAN D. HIRSCH