By Julian D. Hirsch

TAPE RECORDER PROGRESS 1958 to 1977: Modern tape recorders, both open-reel and cassette, perform so well that it is easy to forget how far they have come from their humble begin nings. In order to better appreciate the qualities of today's audiophile machines, I recently reviewed typical performance specifications of tape decks as they have evolved over the years. My source was the Ziff-Davis Stereo Directory & Buying Guide (and its predecessors) going back to the 1958 edition, which was the first is sue in my files. This brought together in one place an on-going listing of products, specifications, and prices, year by year, with sufficient completeness and accuracy to give me the long and detailed perspective I was looking for.

It was clear first of all that the tape hobbyist of 1958 did not enjoy today's almost unlimited choice. Most machines with any pretensions to quality were actually professional or semiprofessional recorders such as the Ampex 601, Magnecord PT-6, and Premier Tapesonic.

And almost all were mono machines, al though stereo was beginning to appear on the scene. After paying from $400 to $600 (in 1958 dollars!), one could expect a frequency response of 50 to 10,000 Hz ±3 dB at 7 1/2 ips and an unweighted flutter level between 0.3 and 0.1 percent (more likely the former). The signal-to noise ratio (S/N) was typically 45 to 50 dB in those days before Dolby and low-noise tapes.

Judging from their specifications, these open-reel machines could be put to shame by most current cassette decks (this is a somewhat misleading conclusion, since open reel always has enjoyed much greater "headroom" compared to cassettes). Nevertheless, there was a hint of things to come in the form of the Sony 555, a stereo recorder with in-line (rather than staggered-gap) heads selling for $525 with built-in power amplifiers, and the Tandberg Model 3 (mono) with a 30- to 16,000-Hz ±2 dB frequency response at 7 1/2 ips, a 60-dB S/N, and only 0.1 percent flutter.

Tape recorders designed for the ordinary consumer appeared in greater numbers the following year, with the $300 Norelco (Philips) Continental capable of 40 to 16,000 Hz (±2 dB) response at 7 1/2 ips with only 0.2 percent flutter and a 54-dB S/N. It could even play stereo tapes, although it recorded only in mono.

Stereo FM broadcasting had arrived by the time the 1960 Buying Guide appeared, and most manufacturers included stereo recorders in their lines. Prices changed little in those days before gal loping inflation, and performance quality likewise remained nearly constant from one year to the next. The Berlant Concertone decks had a 40 to 12,000 Hz frequency response at 7 1/2 ips, with a 45-dB S/N and 0.25 percent flutter, for $495 in mono or $695 in stereo. Heath's first kit-type recorder, with roughly similar specifications, was only $170, however. It recorded in mono but had a stereo play back head.

The year 1961 brought a definite advance in performance, with the Norelco Continental 400 three-speed, quarter-track stereo recorder featuring a frequency response of 50 to 18,000 Hz with only 0.15 percent flutter and a 48-dB S/N at 7 1/2 ips (price: $400). By 1962, stereo machines had become common place, and the upper frequency limit had crept to the 20,000-Hz mark in such diverse machines as the Concertone 505 ($550) and Tandberg 6 ($500). In 1964, the first transistorized recorders made their appearance. Sony's Model 777 had a response of 50 to 15,000 Hz ±2 dB, a 50-dB S/N, and 0.15 percent flutter.

Otherwise, there were few changes from the 1963 listing. Probably the most revolutionary year in home tape recording was 1965, for it marked the unheralded (and apparently inauspicious) arrival of the cassette. The $150 Norelco Carry-Corder 150 was an amusing, battery-operated novelty (I remember being quite unimpressed with it at that year's "Audio Fair") that played or recorded in mono on tape cassettes.

Obviously, we all thought, nothing much was going to come of that, and no one (least of all Philips, who introduced the system) dreamed of the far-reaching effect the cassette was to have on tape recording.

In sharp contrast to their little cassette machine, Norelco also offered the Continental 401 open-reel recorder (all solid state), which featured four speeds (15/16 to 7 1/2 ips) for $300. At the highest speed, the 50- to 18,000-Hz response, 48-dB S/N, and 0.15 percent flutter of the ma chine were typical of the better home recorders of the time.

The semiprofessional and professional recorders, such as Magnecorder and Crown, had also converted to transistors by this time, and the Crown SS700 series had specifications that would do credit to a 1977 recorder. For example, it had a frequency response of 50 to 25,000 Hz ±2 dB at 7 1/2 ips, with a 54-dB S/N, for only $750 in mono and $900 in stereo.

By 1966, the price of the Norelco Carry-Corder had fallen to $120, and its specifications were listed as 110 to 7,000 Hz ±3 dB, with a 45-dB S/N and 0.35 percent flutter. No other cassette machines had yet appeared. Sony's growing line of open-reel recorders was by then fully transistorized, and the tube-type Revox G-36 ($500) was delivering a 40- to 15,000-Hz frequency response at 7 1/2 ips, with a 50-dB S/N and 0.3 percent flutter.

The 1967 directory did not disclose any significant advance in overall performance, although a spate of new models had appeared, from Ampex and Magnecord among others. That year the di rectory carried, for the first time, a separate section for "cartridge" machines (meaning anything other than open reel).

Only a couple of undistinguished cassette recorders were included in this group, and they were apparently meant to compete with the Norelco Carry-Corder. The Teac brand name appeared for the first time in this directory, with several open-reel decks offered in the $500 class. Their ratings of 30 to 20,000 Hz frequency response, 50 dB S/N, and 0.12 percent flutter gave another hint of things to come.

1968 brought a number of small mono recorders in the $100 to $150 range and stereo models priced between $150 and $200. Few members of the industry had yet decided to take the cassette seriously, and the Norelco Carry-Corder had dropped in price to $89.50. Low- to medium-price open-reel recorders continued to proliferate in 1969, spanning a price range from $100 to $500. Even some of the less expensive units had impressive specifications: 40 to 16,000 Hz-±3 dB at 7 1/2 ips with a 50-dB S/N and 0.15 percent flutter. At $300, one could have a frequency response extending to 20,000 Hz. In respect to price, Teac's line expanded in both directions, starting from their $300 Model A-1200.

Although most cassette recorders were still battery portables, a couple of true component decks appeared. The Teac A-20 had a 60- to 12,000-Hz response with 0.2 percent flutter, while Harman-Kardon's CAD-4 featured a 50-to 12,000-Hz response for $180. (The Carry-Corder was now only $65.) 1970 saw the introduction of the Dolby "B" noise-reduction system to the American market in two open-reel machines from KLH. The KLH 40 (at $650) was somewhat ahead of its time, and it was eventually recalled by the manufacturer, but its ratings of 45 to 15,000 Hz at 3 3/4 ips, with 0.1 percent flutter and an astounding 68-dB S/N (with Dolby) were a strong hint of what the future would bring in home tape-recorder performance. The KLH 41, at about one-third the price, had almost the same performance less a number of operating features.

But the cassette had still not broken out of its "low-fi" classification.

By 1971, all categories of tape-recorder performance had begun to advance noticeably. High-price open-reel machines such as the Panasonic RS796, Revox A77, and Teac A-6010 had nearly flat response to 15,000 Hz and beyond, with flutter levels of 0.08 percent and a 55-dB S/N. Just about the same performance could be had in the $300 Tandberg 3000.

The most important development of 1971, however, was the emergence of the high-fidelity cassette deck with built in Dolby noise reduction. The Advent 200, Fisher RC-80, and Harman-Kardon CAD-5, selling between $200 and $250, had a typical frequency response of 30 to 12,000 Hz, flutter as low as 0.15 percent, and the greater-than-50-dB S/N made possible by the Dolby system. Simultaneously with the appearance of these machines, the venerable Norelco Carry-Corder that started it all disappeared from the listings.

The 1972 directory, for the first time, had a separate section for cassette machines in recognition of the fact that they had little in common with the eight-track cartridge machines. The Advent 201 and Wollensak 4760, both at $280, had a rat ed frequency response from about 35 to 15,000 Hz ±2 dB, a 54-dB S/N, and from 0.1 to 0.15 percent flutter. Open-reel recorders, mostly in the $200 to $400 range, continued in strength.

In 1973, four-channel open-reel recorders from Akai, JVC, and Sony appeared at prices from $300 to $650.

There were fewer open-reel stereo machines, but those that remained were generally of high quality and correspondingly high price. Their upper frequency limit had reached and surpassed 20,000 Hz, flutter was as low as 0.06 percent, and a S/N of 58 dB was claimed for Teac's A-6010. And there were, at last, many cassette decks to choose from, with typical specifications of 40 to 12,000 Hz with ferric tape or to 15,000 Hz with CrO2 tape, a S/N of 45 to 50 dB without Dolby (only a few had the Dolby system at that time), and flutter levels between 0.1 and 0.15 percent.

As stereo open-reel decks disappeared from the low- and medium-price categories, four-channel recorders began to take their places in 1974. They carried many brand names, and prices ranged from $400 to $700. A couple of very fine conventional cassette decks, the Tandberg TCD-300 and the Teac A450, appeared with prices of about $400. The Teac machine's flutter rating of 0.07 percent brought the cassette for the first time into direct competition with good open-reel recorders in this respect. The big news of the year, however, was the announcement of the Nakamichi 1000, the first three-head cassette recorder, with a staggering $1,100 price tag. Rivaling the best open-reel decks in most areas of performance, the Nakamichi 1000 probably served more as an indicator of the true potential of the cassette medium than as a threat to open-reel decks in the marketplace.

---------------

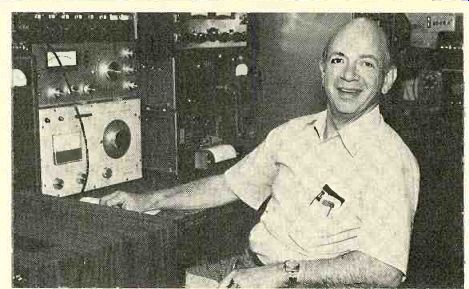

THE FIRST WORD: The salient characteristics of the Norelco 150 Carry-Corder

included a frequency response of 60 to 10,000 Hz 2t.3 dB and a 2-inch round

speaker. The dynamic microphone was separate.

AND THE LATEST: The new JVC Model CD-1636 illustrates the evolution of the cassette format. Its frequency response is 45 to 16,000 Hz ±3 dB, and all of its other specifications are of true high-fidelity grade.

------------------

Prices climbed more noticeably in 1975 after years of relative stability. The open-reel market was abandoned to the high-quality stereo machines and the numerous four-channel models (which, I suspect, surprised some of their manufacturers by carving out a secure niche among low-budget, multitrack recording enterprises, assuring their survival in spite of the declining interest in four-channel recording or playback per se).

The innate superiority of the open-reel format was emphasized that year by Tandberg's stereo 10XD ($1,150) with its frequency response of 30- to 25,000-Hz ±2 dB at 15 ips and 0.04 percent flutter.

There were a large number of cassette decks to choose from, all with generally similar specifications (though not necessarily the same actual performance, "specsmanship" being what it is), and prices in the $200 to $300 range. Nakamichi brought out a lower-price version off their Model 1000, the $690 Model 700.

At about this time, a new phenomenon in cassette recording made its appearance (it actually began in 1974 with the introduction of the Sony TC152SD battery-portable Dolbyized stereo recorder for $300). Having progressed beyond the "toy" stage, cassette recording was ready to become a useful means of making field recordings away from commercial power lines and with the full fidelity of which the medium was capable. By 1976, high-quality, battery-portable, full-featured machines were offered at prices from $380 to $500 by Nakamichi, Sony, Uher, and Yamaha.

By 1976, cassette was indisputably the king, with new decks appearing at an accelerated rate. Front-loading, solenoid-operated transports and more three-head recorders made their appearance. In the better units, an upper frequency limit of 17,000 Hz or so and flutter ratings under 0.1 percent were no longer unusual. The open-reel market was static, being limit ed to the high-end products still popular with those willing to pay from $700 to more than $2,000 for a machine with features and performance not available in the cassette medium.

The situation has not changed much so far in this year 1977, except that deluxe cassette recorders are offered by a number of manufacturers to sell at prices from $500 to nearly $2,000 (!). On the other hand, in the less rarified region from $200 to $400, one can find the vast majority of cassette recorders, mostly of excellent quality. A few more battery-portable stereo machines appeared this year, mostly in the $400 to $500 range; they come from JVC, Sony, Teac, and Uher.

Cassette-recorder performance ratings, which now are doubtless approaching the limitations of the format, are fairly stable. Most can reach 15,000 Hz (at reduced recording levels), and a few can exceed 20,000 Hz. The major effort has gone into improving dynamic range (by increasing recording headroom and reducing noise), so that a SIN of 65 dB or better is no longer a "pipe dream" (tape manufacturers deserve a large share of the credit for this). Flutter is commonly below 0.1 percent, although, since it is affected by the physical construction of the cassette itself, it is difficult to specify cassette-machine flutter with the same assurance as is possible with open-reel.

Open-reel machines, both stereo and four-channel, hold the same place they have occupied for several years. They are expensive (though far less so than true professional machines) and continue to appeal to the serious recordist.

Coming up on the horizon is the elcaset, a new format combining many of the features of cassettes and open-reel tape.

It is too early to predict the degree of success of the elcaset, but we can expect to see several brands of machines avail able in the near future.

In this brief trip along the tape path we have seen extraordinary improvements in performance, to the point that today's cassette recorders far surpass the best home open-reel recorders of a decade or two ago (though not necessarily the semipro machines of that time). Inflation has certainly had its effect on the performance/dollar ratio, but I think it is safe to say that today's consumer gets more for his money than ever before.

Also see:

TAPE HORIZONS--What's Coming Up? CRAIG STARK

TAPE RECORDING--A professional shares his tips on how to do it right, JOHN WORAM