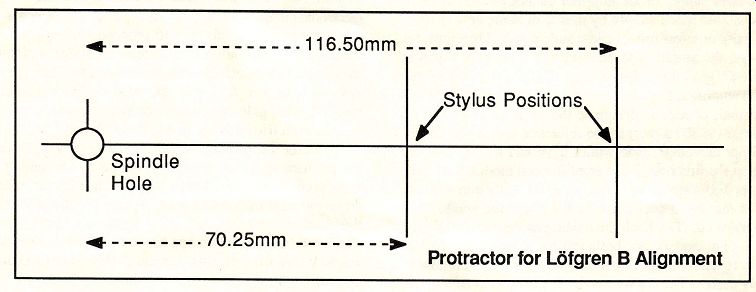

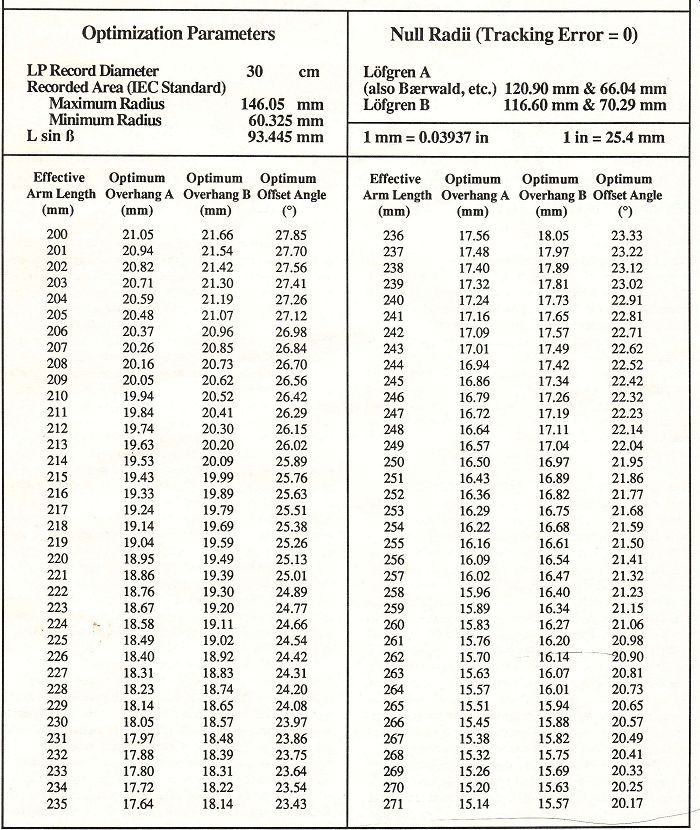

Phonography: Lateral Tracking Alignment Revisited (Maybe Your Overhang Is Wrong After All); Bonus Filler: Diagram of Protractor for "Lofgren B" Alignment; Metric Table of Optimum Overhang and Offset Angle Alignments for Pivoted Tonearms

-------

above: This is a bonus filler for those who may be a little bewildered by the article on the "Lofgren B" alignment for optimum lateral tracking geometry and are wondering where to begin the fabrication of a protractor. The above diagram is drawn to scale but not printed accurately enough to be used as a cutout. Make it from scratch out of reasonably stiff cardboard and lay out very accurately the two null radii marked by the "cross hairs." Dimensions are rounded off to the nearest 0.25 mm.

--------

A re-examination of the key papers published so far on lateral tracking geometry in pivoted tonearms reveals total consensus and consistency, but the granddaddy of all the researchers also suggested an alternative optimization that tends to rock the boat, as it may well be superior to what everybody is blithely using today.

As the tuned-in element in the audio world is well aware, The Audio Critic exerted considerable influence in its early years (especially 1977 and 1978) over the unofficial but almost universal standardization of tonearm geometry that later became more or less taken for granted. We were not the only ones who tried io bring order to the chaos of conflicting practices prevailing at the time; others who were quite vocal on the subject included Mitchell Cotter, Sao Win, Dave Hadaway, Frank Dennesen and Mike Goldstein, the last three of whom even devised and sold various ready made alignment gauges. What made our own contribution unique, however, was an unintended development we were never really comfortable with. It seems that the alignment tables and instructions we published in Volume 1, Numbers 4 and 6 were so handy and comprehensive that they soon became widely accepted as the gospel on the subject and the starting point for all sorts of new designs in tonearms, gauges, protractors, record players, etc.

Now, it is true that we had researched the situation rather thoroughly and gave our readers the best information obtainable anywhere, at least until the present moment.

Even so, our intention was to help audiophiles at home and dealers in their stores, not to provide a free R-and-D package to equipment manufacturers. If it had been our plan to de sign and manufacture expensive phono products, we would have immersed ourselves even more deeply in the subject and hopefully come up with the findings we are only now reporting. (If you wanted to make reflecting telescopes for astronomers, you would not go to the science section of The New York Times for your prime reference, marvelous as it is.) Enter Graeme Dennes, the elucidator.

While we were planning and writing the Winter 1982 83 issue that was never published, we had the good fortune to become acquainted with a remarkable Australian named Grzme F. Dennes, who at the time was working in the American Aerospace industry in California and Georgia.

(Meanwhile he is back in Australia, to the best of our knowledge.) As an avocation, Graeme had delved into the theory, mathematical fundamentals, literature, history and implementations of lateral tracking alignment more thoroughly than any human before or since; his mission was, like Captain Kirk's, to go where no man had gone before- in that particular universe of investigation. He brought to this recreational obsession a scientific impartiality and mathematical savvy that provided desperately needed relief from the effusions of untutored techno-hysterics collecting in our mailbox. His massive thesis, "An Analysis of Six Major Articles on Tone Arm Alignment Optimization and a Summary of Optimum Design Equations," dated March 1983, is a minor masterpiece of comparative elucidation, even if it contains no previously unknown material and has not been printed anywhere, as far as we know.

Originally, Graeme wanted us to publish this heavily mathematical paper in The Audio Critic, but we told him that it would be understood and appreciated only by a small minority of our readership, since it really belonged in the journal of an engineering society. Intent on exposing his work to a broader segment of the audio community, he then wrote a clear and nonmathematical overview of his findings and sent it to us in the form of a letter to the Editor. When he found out that our Winter 1982-83 issue was not happening and that we would not be able to print his letter, he sent it to Audio magazine, where it appeared in the May 1983 issue with a postscript by Barney Pisha, another recognized student of the subject. Dr. Pisha's otherwise thoughtful and receptive comments included the astonishing observation that "with the advent of the compact digital audio disc and the laser beam stylus, all this, of course, becomes moot as it is relegated to the pages of history"-as if new phono cartridges and tonearms were not being sold anymore and mounted on new turntables every day with a need for correct alignment.

There can be no doubt that we are witnessing the waning days of the phono arts and that the century-old technology of a hinged stylus mechanically driven by a rotating spiral groove has a limited future. That does not mean, however, that the millions and millions of music lovers who continue to depend on that technology for their home listening pleasure cannot benefit here and now from the work of a Graeme Dennes. The fact is that the very reason for this article arises from a little-known alternative approach to lateral tracking optimization that nobody but Graeme has ever analyzed comparatively, let alone discussed in print, since its publication 49 years ago and that even he tended to treat only in passing until we started pestering him for more information. It is anything but "moot," as you will see, but first let us summarize the overall thrust of his work as it appears to us from his complete treatise as well as his letters, even if some of our readers remember that 1983 letter in Audio.

Erik Lofgren said it all in 1938.

The six major treatments of the subject that Graeme Dennes compared from the ground up are those of Lofgren in 1938, Baerwald in 1941, Bauer in 1945, Seagrave in 1956-57, Stevenson in 1966, and Kessler and Pisha in 1980. These references are listed more specifically at the end of this article. (The alignment tables and instructions published in The Audio Critic in 1977-78 were based on the work of Baerwald; there is, however, a somewhat inaccurate acknowledgment of Lofgren's contribution in our response to a letter to the Editor in one of our 1979 issues, unfortunately B.D.- before Dennes.) It turns out that Professor Erik Lofgren of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden, had the whole thing figured out from A to Z as early as 1938, three full years before Baerwald. Had there been no further writing by anyone on any part of the subject, one would still be able to mount and align a tonearm and cartridge today with the certain knowledge that distortion due to lateral tracking error cannot be further reduced. It is really quite poignant that a goodly number of highly qualified researchers devoted So many years to solving a problem that someone else had already solved before them. The reason why this was not more widely known until very recently is that the Swedish professor's definitive article is in German and was published in Nazi Germany virtually on the eve of World War I in a technical journal then only in its third year. The exposure in our part of the world was not the greatest, although Baerwald, who published his article in the U.S.A. immediately before Pearl Harbor, does give Lofgren as a reference, without doing him full justice.

After Percy Wilson's pioneering articles in the 1920°s about offset and overhang, it was Lofgren rather than Baerwald who first pointed out that the weighted tracking error (i.e. the tracking error per unit of radius) is the quantity that must be minimized all the way across the record to obtain the lowest possible distortion. That was the conceptual breakthrough. After that the optimization of offset angle and overhang became a relatively straightforward problem in geometry. Graeme Dennes clearly establishes in his paper that all major researchers starting with Lofgren understood the problem completely and solved it correctly, so that it is sheer nonsense to claim that any one of them is right and the others are wrong. (Remember Gerald Bearman and the Formula 4 arm?)

Here are Graeme's conclusions:

Lofgren, Berwald, Seagrave and Stevenson produced mathematically identical, and exact, design equations for optimum offset angle and optimum overhang, differing only in notation and arrangement. Their solutions result in the familiar three-point, equal weighted tracking-error curve with two nulls, on which today's widely accepted alignment practices are based. In addition, Lofgren and Baerwald also produced identical, but approximate, equations for overhang.

Bauer's offset angle equation is an approximation, and his overhang equation is identical to the Lofgren/Baerwald approximation (not their exact solution). Seagrave also produced an approximation for overhang, different from that of Lofgren/Baerwald/Bauer and actually more accurate. Thus we have a single exact solution from four different sources so far, plus three different kinds of approximation that are also correct as far as they go.

Now comes the best part. Lofgren and Stevenson each presented still another approach, one quite different from the other. The aim in each case was a further reduction of the psychological annoyance factor of tracking distortion. The Stevenson rationale can be easily dismissed today, after more than 21 years, because it was obviously influenced by the typical styli of the era. Stevenson considered tracking and tracing distortion in the neighborhood of the innermost groove to be so annoying, albeit of brief duration, that he preferred his inner tracking-error null to be established at the radius of the innermost groove, rather than about a quarter of an inch further out as in the classic solution. A slight increase in overall tracking distortion across the playing surface was the trade-off, quite unnecessary today because the various modern line-contact styli trace the innermost grooves better than a 1966 spherical stylus did the outer most, so that inner-groove tracking distortion is no longer aggravated by tracing distortion. The Lofgren alternative, on the other hand, which we shall call the Lofgren B alignment (Lofgren A being identical to Baerwald's and our 1977-78 tables), deserves the most serious consideration.

Lofgren B: the surprising advantages.

Lofgren's alternative optimization was based on the assumption that the annoyance factor of tracking distortion is cumulative with time and that short stretches of slightly higher distortion are therefore more tolerable than long stretches of relatively lower distortion-just the opposite of Stevenson's approach.

The classic (or A) alignment results in three equal peaks of weighted tracking error, and therefore of tracking distortion, as the stylus travels across the record: one at the outer groove, one at the inner groove and one between the two zero-error points (or nulls). On either side of the middle peak, between the two nulls, the weighted tracking error changes relatively slowly with the radius and hence with time. The annoyance factor comes into play. By minimizing the integral of the distortion function weighted by the application of the method of least squares, Lofgren proposed to reduce the middle peak and obtain lower tracking distortion over the long, slow stretch between the two nulls, thereby alleviating the annoyance factor. The price to be paid for this is the automatic increase of the other two peaks, at the outer and inner grooves, but the resulting higher tracking distortion is of relatively short duration and therefore has little effect on the annoyance factor. In terms of actual dimensions, the Lofgren B alignment results in the same optimum offset angle as A, a slight increase in optimum overhang over A, and a fairly sizable relocation of the two nulls. Therefore, new alignment tables and/or new gauges and protractors are required.

Graeme Dennes is neutral when it comes to expressing a preference between Lofgren A and B, since both are mathematically correct and exact solutions in terms of the underlying assumptions. The A alignment minimizes peak distortion at the expense of total, continuing distortion; the B alignment minimizes total, continuing distortion at the expense of the short-term peaks. It is our impression that Lofgren himself leaned toward B, and we are also inclined to favor B after examining the trade-offs.

Let us compare. Both alignments result in two nulls, where the tracking error, weighted and unweighted, falls to zero and so does tracking distortion. In the vicinity of these two points along the arc described by the stylus, the sound is the best possible with either alignment, although the two points are not identically located. So far, no preference.

Now, between the two nulls, where more than half of the playing time falls, the B alignment sounds better because the tracking distortion is held to lower values. B moves ahead. At the very beginning and very end of the record, the A alignment sounds better because the tracking distortion peaks are not as high, but the first better passage is soon over, and the second does not even happen on discs that are not recorded close to the label or else is equally brief. So the A alignment does not quite catch up in the trade-offs, and therefore B wins, at least in our book.

It should be pointed out that the above conclusions are based partly on logic and partly on informal listening tests, each confirming the other. The differences are audible but small, since the geometrical difference between A and B is also small. Considerably more rigorous listening tests were conducted some time ago in California by Sao Win, whose fine credentials as a phono technologist are matched by the keenness of his hearing and his musical taste. Sao is more enthusiastic about Lofgren B than any of the afore mentioned dramatis persona and claims that his new stylus geometry, discussed elsewhere in this issue, makes the superiority of the B alignment even more obvious.

Incidentally, before the publication of the new alignment table accompanying this article, the only parties privy to the exact IEC-normalized values of the Lofgren B zero tracking-error radii, as far as we know, have been Graeme Dennes and friends, Sao Win and friends, and your Editor and friends. Thus there has never existed a sufficiently large sample of initiates for the purpose of testing the alignment and comparing notes.

Where do we go from here? We are not going to repeat here the nuts and bolts of tonearm mounting, cartridge and arm jockeying for accurate alignment, protractor fabrication and use, etc., which we published in 1977-78. These things are common knowledge today-or ought to be. All we wanted to communicate at the twilight of the phono era is that an almost forgotten in sight by a very early pioneer may help you obtain a small improvement in sound quality from your records.

It would be even better, of course, if a straight-line tracking (SLT) tonearm became available that incorporated the refined construction details and superior mechanical characteristics found in the very best pivoted arms today.

That would indeed make all of the above "moot," but we have yet to see and hear such an arm, although we cannot state categorically that it does not exist.

At this point, our recommendation is that you try the Lofgren B alignment with the aid of our new table of optimum values and just listen. We hope you do not have to drill a new hole for your tonearm to achieve the increased overhang but can simply move the cartridge forward in the headshell or else discover sufficient play in the existing hole. As for the makers and marketers of factory-assembled turntable/tonearm systems, and of ready-made alignment gauges and protractors, we shall just sit back and observe how they handle this one.

References:

1. Erik Lofgren, "Uber die nichtlineare Verzerrung bei der Wiedergabe von Schallplatten infolge Winkelab weichungen des Abtastorgans" ("On Nonlinear Distortion in the Reproduction of Phonograph Records Due to Angular Deviations of the Pickup Device"), Akustische Zeitschrift, 3 (Nov. 1938), 350-362.

2. H. G. Baerwald, "Analytic Treatment of Tracking Error and Notes on Optimal Pickup Design," J. Soc. Mot. Pict. Eng., 37 (Dec. 1941), 591-622.

3. B. B. Bauer, "Tracking Angle in Phonograph Pickups," Electronics, Mar. 1945, p.110.

4. J. D. Seagrave, "Minimizing Pickup Tracking Error," Audiocraft Magazine, Dec. 1956, p. 19 (Part 1), Jan. 1957, p. 25 (Part 2), Aug. 1957, p. 22 (Part 3).

5. J. K. Stevenson, "Pickup Arm Design," Wireless World, May 1966, p. 214 (Part 1), Jun. 1966, p. 314 (Part 2).

6. The Audio Critic, Vol. 1, Nos. 1, 4, 5 and 6 (1977-78).

7. M.D. Kessler and B. V. Pisha, "Tonearm Geometry and Setup Demystified," Audio, Jan. 1980, pp. 76-88.

++++++++

Metric Table of Optimum Overhang and Offset Angle Alignments for Pivoted Tonearms

Optimization Parameters; Null Radii (Tracking Error = 0)

LP Record Diameter 30 cm Recorded Area (IEC Standard) Maximum Radius

------------

Lofgren A (also Baerwald, etc.) 120.90 mm & 66.04 mm

Lofgren B 116.60 mm & 70.29 mm

1 mm = 0.03937 in

1in =25.4 mm

--------

[adapted from TAC, Issue No. 10]

---------

Also see:

Today's Audio Equipment and the Reviewing Discipline: Where We Stand: Loudspeakers; Power amplifiers; Preamplifiers and control units; Turntables and tonearms; Phono cartridges; CD players; Other program sources; Speaker wires and audio cables

Various audio and high-fidelity magazines

Top of page