Box 978: Letters to the Editor

(Please note new address!)

We have been getting exactly the kind of mail we want for this column, so we must conclude that our ground rules for publishing letters as set forth in No. 10 and No. 11 have sunk in. Let us reiterate that any communication of serious editorial interest coming from a reasonably credible source is likely to be published. Letters may or may not be excerpted, at the discretion of the Editor. Ellipsis (...) indicates omission. Address your letter to The Editor, The Audio Critic, P.O. Box 978, Quakertown, PA 18951.

The Audio Critic:

Referring to some of your comments in Issue No. 11 regarding the audible significance of D/A errors of the order of a few LSB's, I thought that you might be interested in our findings. (Namely the paper presented at the 84th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society in Paris, March 1988, "Are DIA Converters Getting Worse?" by Stanley P. Lipshitz and John Vanderkooy, a preprint of which was en closed with the letter -Ed.) As you will see, many current CD players (even expensive ones) have errors of 4 bits or more. As you'll see on p. 35, we believe these to be audible on suitable music at normal levels, and thus too large. We would like to see D/A errors at low levels held to under 1 LSB.

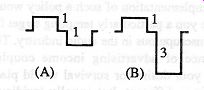

By the way, I disagree with your statements in the 2nd paragraph of the 2nd column on p. 34 of Issue No. 11 that on the -90.31 dB dithered signal a 3 dB level error amounts to a 1/2-bit error, 6 dB to a 1 bit error and 12 dB to a 2-bit error.

---- (A) B)

The 90.31 dB signal is 2 LSB's high, (A) ideally. A 2-bit monotonic error on this results in (B), which to first order is twice as large and will have a fundamental component about 6 dB (not 12 dB) too large.

This is, of course, approximate, as this is a severely distorted reconstruction. See, for example, Fig. 38 of our preprint. A 16-LSB monotonic error results in a level error of about 20 dB due to the peak-to-peak signal amplitude being increased from 2 LSB's to 18 LSB's. You're thinking of 6 dB per bit-but this is number of bits in binary word, not number of LSB's in signal.

I'd like to suggest that you try to duplicate some of our experiments and see what you think is acceptable in terms of low-level ("crossover-type") linearity errors. I'd be interested to hear what you find.

Good luck with the resurrected publication. Some sanity is all too rare in this field of popular publishing.

Yours sincerely, Stanley P. Lipshitz Audio Research Group University of Waterloo,

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

Thank you for the paper; its reputation had already reached us by the time we received your preprint. It is without doubt the best, most complete and most interesting investigation so far of the key issues in digital-to-analog conversion; CD player testing will never be quite the same again, at least not in our laboratory. (Our readers are directed to the digital article in this issue for further details and comments.) It is most kind of you, as a professor of mathematics and distinguished audio theoretician, merely to "disagree" with our sloppy digital arithmetic when you could have subjected us to a withering put down, such as we have occasionally deemed fair play under comparable circumstances. We stand corrected, of course, and our only excuse is the pressure of time, the parenthetical bit numbers having been inserted into the paragraph in question as a last-minute editorial afterthought just before an already delayed issue went to press. Our overall conclusions, however, remain unaffected by these computational lapses. (Again, see the digital article in this issue for emendations.) Needless to say, we are proud and happy to have you among our well-wishers for whatever reason, but we think the main polarization in "popular" audio journal ism is not sanity vs. craziness but account ability vs. irresponsible self-indulgence.

-Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I would think that raising the Q of the drivers to compensate for dipole cancellation (as in Carver's Amazing Loudspeaker) would flatten the amplitude response at the expense of transient response and group delay characteristics. Electronic equalization would have the same effects plus the additional drawbacks you mention. I thought it unusual that you made no mention of pulse reproduction or tone-burst testing with the Carver speaker.

I bought my first copy of Stereo Review in years, partially because of the compliment you paid them on page 30.

There the Dahlquist DQ-20, which you blasted for lack of coherence, was being lauded for "excellent phase linearity...confirmed by its group delay, which was within +/- 0.2 millisecond from about 2,500 to 28,000 Hz." Any idea why there is this discrepancy? Sincerely, Robert S. Green Palatine, IL You appear to have missed the main point of the Carver bass design. The open baffle is, in effect, equivalent to a very low Q enclosure for the high-Q drivers. The resulting system Q comes out in the right place, analogously to the more familiar case of a low-Q driver in a conventional high-Q box. Since it depends on the self cancellation of opposite-phase wave launches, the desired system Q of the Amazing comes together only at some distance past the nearfield, but that is where You sit, and there the transient response of the bass system has the appropriate lower Q characteristics. Electronic equalization, as in the Enigma or Celestion 6000, is the brute-force way to achieve the same end result in an open-baffle system when starting with low-Q drivers.

The Carver speaker has a single crossover at 100 Hz, low enough to make pulse coherence a moot point, as we explained. At higher frequencies the monolithic ribbon is of course coherent, being driven in phase over its entire surface. Its tone-burst response is fine.

As for Stereo Review, you must under stand that Julian Hirsch is a bit uncomfortable with loudspeaker testing because some loudspeakers are devastatingly superior to others and that goes against the editorial grain of the magazine. He uses some kind of personal-computer software with FFT capability and gets an automatic readout of group delay, which he then reports only for the range of frequencies in which the figures are acceptable. For ex ample, when he reviewed our own highly coherent Fourier 6 speaker in 1984, he gave group-delay figures for "most of the audio range," whereas in the case of the Dahlquist he apparently prefers to talk only about the tweeter range. Give us a break! The DQ-20's main discontinuity in wave-front coherence is from woofer to midrange, once the tweeter is out there on its own there is nothing to create discontinuity. The tweeter happens to be a very good one; what we questioned was the crossover.

We suspect that the whole thing makes little difference to most Stereo Review readers, who probably believe that group delay occurs when Fleetwood Mac's plane arrives late at the airport.

-Ed.

The Audio Critic:

Great to have you back at your old, enlightened, technical, acerbic self. Stay nasty! But-how dare you print the cartoon on page 15 of Issue No. 11 and still have the audacity to print the warning on the in side front cover that reads, "Reproduction in whole or in part [of the contents] is prohibited... The Audio Critic will use all

[emphasis mine] available means to pre vent or prosecute any such unauthorized use of its material or its name." Does "all" include the FBI? Are your "talents" more worthy of protection than Emmylou Harris's? May I copy The Audio Critic for my indigent relatives for significant holidays? Or is it only OK for "mom"?

Sincerely, Alex Zonn

Los Angeles, CA

P.S. Tom's cartooning abilities have certainly improved. Will we be seeing his work in the Los Angeles Times soon? Will they (his abilities/talents) be worthy of protection then or are they now? First of all, we are unaware of being nasty, but it is possible that in Southern California any civilized individual is perceived as having a streak of nastiness.

Secondly, your ellipsis slyly eliminates from our masthead the key words, "without the prior written permission of the Publisher." Such permission has always been granted in the case of articles and reviews reproduced in their entirety and of short quotations without obvious out-of-context falsifications of meaning. As for bootleg Xeroxes, we believe that in the long run they bring in more new subscriptions than they circumvent, a business philosophy shared by the publishers of personal-computer software without copy protection, to name just one enlightened example. The original uptight Emmylou Harris of underground audio publishers was actually J. Peter Moncrieff, who in 1980 and 1981 had his IAR Hotline! print ed on Xerox-proof red paper in green ink, until he realized that his subscribers were going blind trying to read his reviews and that pirating the latter was not exactly a top priority of the underworld.

Lastly, Tom was only 15 years old when we stopped publishing; now he is 22 and about to graduate from the School of Visual Arts in New York, so it behooves him to show an improvement. It so happens that Sci-Tech Information, a bulletin of the National Bureau of Standards, requested and was given permission to reprint the comic strip in question free of charge, and Tom did not throw an Emmylou tantrum. Thank you for your concern about these matters.

-Ed.

The Audio Critic:

Having recently completed reading [Issue No. 11] of The Audio Critic, it occurred to me that you may have over looked another, and perhaps more potent, argument than that you have already advanced in support of your new advertising policy.

As I understand the position, your "old" policy was based upon the potential conflict of interest between your ethical responsibilities as a journalist on the one hand, and your desire to run a profitable and financially viable enterprise on the other.

As you have conceded that the lack of advertising revenue may have been a significant factor in the demise of the original Audio Critic, and given that you presumably do not wish to repeat that failure, there would exist a real risk that you may now be deflected, consciously or other wise, from your obligations as a journalist in accepting paid advertising.

However, it could be argued that a continuation of the old policy carried just as great a risk of corruption, in that the special reputation you may develop through the implementation of such a policy would make you a particularly tempting target for the unscrupulous in the audio industry. The absence of advertising income coupled with your desire for survival would place you in a different, but equally insidious, conflict of interest.

In the final analysis, we are wholly dependent on the ethical standards of you and your staff.

It is therefore of some considerable concern to me to note what appears to be a significant breach of faith on the part of The Audio Critic, ironically as a result of advertisements in magazines such as Stereophile, apparently placed by, or on behalf of, The Audio Critic.

Specifically, I am referring to the series of advertisements informing readers of the imminent resurrection of your publication. Such advertisements clearly stated that the same "editorial format" would be followed in the new magazine as the old.

I take it that you would not dispute that advertising policy falls within the ambit of "editorial format." I also take it that you would not dispute that such was a fundamental plank of same.

As these advertisements ran for a lengthy period of time without any correction or disclaimer, it is difficult to accept that you had been unaware of their content.

Indeed, your recent comments in [Issue No. 11] show that it was a matter to which you had adverted your mind, and anticipated criticism.

Even when viewed in the most favor able light, the advertisements were mis leading. It was to be "just like the (good) old days," or so we thought! In the absence of any indication that the change in advertising policy took place after the placement of those advertisements, the inference that you knowingly allowed the publication of false or misleading material is almost irresistible.

This is a matter of real concern to me, and no doubt to many of your readers-it goes directly to that most vital of issues: your credibility. If you are able to provide a benign explanation, I would be most grateful to hear it.

Yours faithfully, Clive P. Locke; Sydney, Australia

Our comprehension of Australian manners and mores extending very little beyond Crocodile Dundee, we are not sure whether you are serious or just pulling our leg. Are you just parodying the exquisite fraternity of hairsplitting ethics buffs (high-end audio subchapter), or are you a down-under blood brother of Marc Rich man (see Issue No. 11, p. 6), fiercely guarding our morals, always hoping to catch a bishop in the whorehouse? Well, we have news for you, mate. Not one of our readers, other than yourself, has written or spoken to us so far regarding this "matter of real concern." To us, the words "editorial format" denote the physical appearance (size, layout, typography, etc.) and general approach to writing (style, features, columns, recurrent subjects, etc.) of a publication, not its business policies or sources of revenue. Had we felt that our decision to accept manufacturers' advertising would be a red-flag issue to potential subscribers (as it turned out not to be, not even marginally), we would certainly have announced it, even though no pages had been sold yet when our original classified ads were written.

We love your implicit suggestion that taking bribes was as great a danger under our old policy as becoming a lackey to the advertiser is now. You have a wonderfully dirty mind, and it has been said that a dirty mind is a perpetual feast. The conspiracy theory of audio reviewing, paranoiac and tiresome as it is, will never die because outsiders have no idea how little money there is in being dishonest in this business.

Of course, it is possible that all we have here is a bit of semantic confusion.

Maybe "editorial format" has a totally different meaning to an Aussie. We have no idea what "Waltzing Matilda" means, either. G' day, mate.

-Ed.

The Audio Critic:

Your reentry into the world of publishing promises many an interesting and controversial discussion.

I note with interest, for instance, your latest position statement on amplifier (and preamplifier) "sound," perhaps prompted by your experience with Bob Carver's massaging of one of his amplifiers to sound "exactly like" another. Based on this, and other experiences with ABX comparison, you now conclude that in the absence of level or frequency-response differences beyond 0.15 dB, or gross distortion mechanisms, any and all amplification is provably indistinguishable from any other of the same variety (i.e., power amp com pared to power amp).

(Not quite. What we suspect, rather than conclude, is that any claim of audible differences under said conditions will re main un-provable. Slight difference -Ed.)

...I cannot disagree in principle with your conclusions, as far as they go. I have long since grown weary of the fatuous statements of the "measurements are meaningless" variety, ascribing Olympian feats of imaging, depth, stage width, etc. to the poorest-performing products, in language more suited to an Elizabethan suitor than a reviewer of electronic hardware. I have long believed that a better-measuring product will tend to sound better, and vice versa. In short, accuracy is the goal we have pursued, and accuracy can be demonstrated empirically.

It is, as you have found, relatively easy to set up a so-called double-blind test, carefully matching levels, and to conclude on the basis of statistics that no reasonably accurate amplifier is able to be sonically trounced by another. To conclude, in fact, that audible differences, if they exist at all, are so trivial as to beggar description or concern. We, in our own double-blind listening test, can prove nothing else. This is among the reasons we have always said that products of this type should be selected on the basis of demonstrated reliability, proven customer-oriented service policies, observable quality of componentry, rational pricing structure, intelligent engineering, projected resale value and company integrity, as much as sound quality. But we do include sound quality in our list of purchase decision criteria, careful not to make grandiose claims for our own gear, or to denigrate any other, merely admonishing the prospective customer to listen carefully, at leisure. Observe how one reacts to the music, not necessarily trying to "hear" the electronics.

Why? Because we have been, as manufacturers, privy to information which an audio reviewer, professional or otherwise, would have no way of duplicating.

A little background is in order here.

We have long held to the belief that "new, improved" model designations for every minor tweak in the construction of a product are a cynical, shortsighted marketing strategy. Thus, we have always merely included improvements in our products in the normal manufacturing process, with no announcements or model-number changes.

This has given us some unique opportunities to observe unsolicited reactions to the same products, but with improved (measurable) performance. The results have been instructive. In one very early example, we discovered that a resistor in the feedback loop of our amplifiers had a temperature coefficient which showed up in the THD measurements at low frequencies because of the relatively long heating and cooling times, actually changing the gain minutely twice for each cycle, thus showing up as a harmonic component. The heating/cooling cycles integrated over the waveform at higher frequencies, thus the measurable effect disappeared above about 100 Hz. Keep in mind that we are talking about a mechanism which was rather subtle in its action, generating a worst-case increase in THD of less than 0.005% at 20 Hz, full power, and proportionately less at lower output or higher frequencies. We had not been in production very long at this point, over 10 years ago, and we were a bit embarrassed that this phenomenon had escaped our attention even as long as it had. We substituted a low-temperature-coefficient metal film resistor in this spot in production, with no announcement, naturally, of any kind.

Over the next month, we had at least one call per day, sometimes two or three, from our dealers all over North America asking,

"What did you guys do to the bass? It sounds tighter somehow, better defined." My initial reaction was to dismiss this as coincidence; nobody, I thought, could possibly hear a change that minute, especially with no reason to suspect there was a change in the first place. But as I continued to field the calls from dealers, I finally started wondering if it was possible, provable or not.

The concept was intriguing enough that we decided to test it on a more or less formalized basis. If and when improved technology made it possible to measurably advance the performance of our products, we deliberately made no mention of it to anyone, but just shipped it in place of the older circuitry as production continued. In each case, we had a flurry of contact, by phone and letter, asking about or mentioning the "smoother top end," or the "overall increase in transparency," depending on where the actual specs had changed.

It almost became an in joke at the factory. "Don't make that change in the circuitry until next month; we're too busy and we haven't got time for the phone calls right now." A couple of years ago, in an extreme case, we revamped the entire output section of our amplifiers, to a configuration we call "quad-complementary," whereby we use complementary pairs of output devices on each side of the power supply, with each complementary pair fed from a single driver transistor. This negates the minor but measurable differences in overall characteristics between NPN and PNP transistors, and very much linearizes the transfer function, especially around zero crossing.

It reduced the THD and IM numbers across the band by about 6 dB, or a factor of 2, while tilting the distribution of the remaining distortion downward to reduce the contribution of the upper harmonics much more than just THD numbers would suggest. Needless to say, we expected a reaction and we got it. It was not mild.

One dealer's reaction was typical. "I just got a new 4B amp in and decided to hook it up in my demo system and cycle out the one I've been using the last few months. I want to return the older one because now I believe it's defective." One dealer got in an example of the new production and phoned immediately to order a replacement for it. He was going to take it home and never sell it because he was afraid it was a fluke we could never duplicate! Obviously, all the above boils down to anecdotal evidence and is by its nature un-provable. Yet we cannot deny that it happens, time and again. It is maddening that we could probably set that same dealer, who was going to take the "fluke amplifier" home, in front of an ABX-box system and derive nothing but guesswork statistical results. Yet he didn't call us the week before, or the month before, when there were no changes. He called us the minute he first hooked up the new circuit, with no advance notice it was even there, practically shouting at us over the phone, along with literally dozens of others. We have had to resign ourselves to existing in what I have come to call "a Zen world of dual realities." We don't express an opinion on this; we merely improve our product wherever and whenever we can, observe the results, and wish we could "prove" that it makes an audible difference.

As an aside, if this second reality has any pertinence to your tests with amplifier nulling, such as the original Carver vs. Levinson setup, whereby you were able to obtain a momentary null as deep as 74 dB, it would be this: Keep it in mind that the best amplifiers have distortion spectra 95 to 100 dB below the music, and a null of 70 to 75 dB still allows for differences of considerably more than an order of magnitude in distortion mechanisms. A null of 70 to 75 dB consists of equalizing out frequency response and phase-shift differences, and as you pointed out, it is in essence a one way street. A reasonably good product can be brought down to the level of a relatively poorer one, at least within the rather broad limits a 70+ dB null constitutes. Going in the other direction is obviously quite a different story. No amplifier with a --75 dB distortion spectrum (about 0.02%, well within the realm of the big true-class-A amps) can ever "null" better than that against a product with --95 dB broadband spuriz, no matter how much tweaking is done. If people are even unconsciously responding to that last 20 to 25 dB, no amount of observable, provable, empirical data is going to convince them it all sounds the same and to look elsewhere for the real answers to their questions about sound quality.

Sincerely, Christopher W. Russell Vice-President, Engineering Bryston Ltd.

Rexdale, Ontario, Canada

Those of our readers who still have a copy of Vol. 1, No. 4 stashed away some where may find it amusing to go back to your 11-year old letter on p. 42, Chris, and note your Faustian evolution from high tech quest to spiritual enlightenment.

Since you do not disagree with us in principle, we might as well accept your "anecdotal evidence" at face value. Of course, anecdotal evidence also exists in support of extraterrestrial visitors, faith healing and levitation, all of which would be almost as nice to believe in as the audible superiority of amplifiers with "-95 dB broadband spurice." We have an article in this very issue on the subject of conventional/traditional audiophile wisdom vs. double-blind listening tests, so it would be redundant for us to put forth the same thoughts here. Let us merely observe in passing that your "Zen world of dual realities" is far too good for the high-end audio business to be entirely above suspicion, although we do believe that your excellent products are also viable in a Cartesian world of certitudes.

-Ed.

The Audio Critic:

It's wonderful to have you back. A major difference between The Audio Critic and most other alternative audio publications is that you are more often able to give reasons why one item sounds different from another, rather than merely observing that there is a difference. Your voice has been sorely missed.

Why isn't the output of a vent misaligned in the time domain with the driver's output. Surely it must take some amount of time, no matter how minute, for the sound waves to travel from the back of the driver to the vent outlet. How then can this sound possibly be properly synchronized with that driver's direct radiation?...

Sincerely, Douglas Weinfield; Silver Spring, MD

Vive la difference between us and the undisciplined subjectivists.

At very low frequencies, where the vent is active and where the wavelength is incomparably greater than any of the various dimensions and spacings of the system, the driver and vent can be regarded as a single coincident source with an output equal to the vector sum of their individual outputs. This has been explained more precisely and in greater detail by both Beranek and Small. Your fear of non-synchronicity stems from popular caveats applicable only to considerably higher

[frequencies with shorter wavelengths.

-Ed.

The Audio Critic:

I was pleased to note in your review of the Hafler XL-280 that you found it to be a fine amplifier. I was disappointed, however, to note that you tried to disparage our concept of trying to make the amplifier indistinguishable from a straight wire. This is inconsistent with your previous writings on this topic.

When Bob Carver doctored his amplifier to make its sound identical with a Mark Levinson model, you praised this technique. Now, when we have made our amplifier indistinguishable from a straight wire, using an identical concept, you condemn it.

Of course, "straight wire" is a figure of speech. What we are really saying is that the output of the amplifier should linearly follow its input at all frequencies and at all dynamic levels. That would be the ideal amplifier-a goal which is impossible to achieve. Fortunately, in practice we need only achieve this for the audible frequency range, and this is possible as demonstrated with the XL-280.

With the XL-280, the difference signal between amplifier and "straight wire" is down better than 70 dB and is inaudible when listening to "normal" signals such as music or white noise. I concede that with wider-band, more dynamic signals, and with better-quality transducers and ancillary equipment, plus sharper ears, the difference signal might be audible. That is a problem for the future. For the present the XL-280 cab be demonstrated to be a very accurate amplifier-more accurate than any which we have tested to date.

You have criticized the XL-280 as not having a flat response outside the audio range. This was done, of course, to make a better amplifier within the audio spectrum.

The trimmer which modifies the ultrasonic response adjusts the phase shift in the upper audio range and compensates for the change in phase shift which occurs with different loudspeaker loading. We have found that changing the high-frequency load, as happens with loudspeakers, causes small response variations in the audio range. These variations are one of the causes of sonic differences between amplifiers which are affected differently by different loudspeakers. Our trimmer permits reduction of this amplitude distortion so that the amplifier's performance is closer to that of a straight wire and can be optimized for a specific loudspeaker.

The effects of this trimmer capacitor are audible with some program sources and some loudspeakers, so the adjustment is meaningful.

The small rise in frequency response above the audio band brings the phase shift close to zero within the audio spectrum.

There is a question as to whether phase shift is audible, but minimizing it certainly cannot be detrimental.

You refer to "scientific truth" calling for a "perfect" amplifier to be a low-pass filter having flat response up to a certain high frequency (unspecified) and rolling off with a controlled slope (unspecified) above that point. What authority has pontificated this "scientific truth"? Who can say whether a roll-off is better or worse than a rise in response? Does a spike on the leading edge of the square wave sound better, worse, or the same as a rounded corner due to a roll-off? Fortunately, we do not have to answer these questions. The Straight-Wire Differential Test bypasses them. If the sound output from the differential comparison between amplifier and straight wire is in audible, the amplifier is accurate regardless of whether its ultrasonic response is flat.

The logic is irrefutable--an inaudible null means the amplifier sound cannot be differentiated from that of the straight wire, and that is as good a reference standard as can be found.

If you yourself believe what you have written about the Carver comparisons with various amplifiers, then you must accept the validity of the straight-wire comparison. Of course, some fine amplifiers might fail the test strictly on the basis of some relatively unimportant phase shift. However, the amplifiers which pass it, such as the XL-280, should be praised for their design achievement.

Sincerely, David Hafler, The David Hafler Company Pennsauken, NJ

Let us not forget, first of all, that what we are disputing here is a very narrow strip of purely conceptual territory. The disagreement between us is for the most part academic, rather than the typical reviewer vs. manufacturer hassle about hardware, so there is really no reason for tempers to rise. "Pontificate" seems to us a bit ill-tempered (although we are not familiar with it as a transitive verb), so we want to make it quite clear, Dave, that we are on your side on nearly every issue in audio and have been so inclined ever since our original audio mentor, Stew Hegeman, told us in the mid-1950's that "when Dave Hafler tells me something about an amplifier, I know it's a fact without having to check it myself." You have no cause to regard us as an adversary.

That said, we are just about as uncomfortable with the concept of your SWDT after your letter as we were before, despite the almost irresistible chutzpah of your suggestion of a resonant condition as no less valid than a nonresonant one when modeling the ideal transfer function. Why not, indeed? On what marble tablet is it engraved that our theoretical low-pass filter must have a low Q? But wait a minute, a straight wire does not have a resonance at 365 kHz with a Q of 2, does it? It does not impose a leading-edge spike on a square wave, does it? What you are really saying, at least as we hear it, is that the amplifier should be like a straight wire within the audio range and, by necessity, like a very kinky wire above the audio range. That is a most inelegant model to our mind, and we cannot buy it. What we discern here is a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy: you structured a specific test which your amplifier then passed with flying colors.

The true bone of contention here is the audibility of those small phase shifts at the highest frequencies of the audio spectrum, or more simply and precisely the audibility of the small but inevitable signal delay through the amplifier. You are a bit schizoid about this, going to unprecedented extremes to wash out the delay while obviously doubting its audibility in actual performance. We say, leave it alone. It is as natural a part of an amplifier's attributes as your shadow is a part of yours-and just as harmless. That, incidentally, was the basic position we took regarding Bob Carver's input/output null test (his "other" test-see Issue No. 10, p. 36, 2nd column, and p. 37, Fig. 2). There is absolutely no inconsistency in our views here; the "praise" you remember had to do with his main null test, the one we were primarily focusing on, which proved that two totally different amplifier circuits could have exactly the same transfer function. That had an important demythologizing effect.

Being critical of your trimmer does not mean we are against null tests all of a sudden.

To repeat, this Lilliputian controversy does not change our generally favorable opinion of Hafler engineering and Hafler products; we still believe, however, that the SWDT is essentially a marketing concept.

-Ed.

The Audio Critic:

Thank you very much for the review of the Win FET-10 cartridge and your kind words about me and my work in general. I am flattered, and perhaps a little embarrassed, by your characterization of me as "the most sophisticated of phono technologists." I must confess in all honesty that considering the amateurish design work which prevails in cartridge and turntable technology today, sophistication within this realm is quite relative.

I was also a little surprised by your discussion of the decline of the phono graph. I think the decline most worth discussing is in the general quality of recorded music brought on by the widespread adoption of imperfect digital systems by the recording industry. I am certainly not against digital, and I do not propose to freeze the technology, but I truly believe that a strong case can be made for analog by some fundamental rethinking of the basic design of playback systems.

On the basis of my fundamental re search, the vinyl disc still has the ability to store a signal and redeliver it on playback equipment with a level of quality surpassing that of all other systems currently available or projected...

...While it is true that the phono equalization sections of all preamplifiers have tremendous amounts of phase shift between 20 Hz and 20 kHz, this phase shift exactly complements the phase shift of the pre-equalization circuits used in cutting records. So with a well-recorded vinyl disc and a well-designed preamplifier, the sys tem phase response is nearly perfect. In a system like the Win FET-10 cartridge, which is an amplitude sensor, and with the RIAA preemphasis characteristic not far from constant amplitude, this phase shift is almost nonexistent, thanks to the absence of the violent equalization networks necessary with most moving-coil and magnetic cartridges.

In regard to the frequency response and channel separation which you perceived in the FET-10, our research has shown that test records suffer from inaccuracies within this spectrum. Most cartridge manufacturers use the Bruel & Kjaer equipment with their test records QR 2009 or QR 2010. Although B&K is the dominant equipment, there are other test records based on the General Radio recorder, viz. the CBS STR series.

We used our B&K equipment with the following test records to substantiate your findings in the review of the FET-10: Denon 7001, JVC TRS-1007, AT-6005, B&K QR 2010. As a further check on our measurements, we had data run on the same cartridge using the General Radio recorder and the CBS STR-100, 170 and 112 test records. The chart of the channel separation data is provided. It can be seen that the Japanese test records yield higher separation figures, in general, than the CBS test records, outstripping them by 6 to 10 dB at 1 kHz. Only the JVC TRS-1007 test record provided a channel separation figure that is close to our exciter measurements.

An oscilloscope trace of the test cartridge from the CBS STR-112 square wave test record [shows] the characteristic ringing that many magazine reviewers attributed to resonances in cartridges that they have tested over the past two decades.

To examine this hypothesis, the disc was played at different speeds from the standard 33.33 RPM. If the ringing was indeed the artifact of our test cartridge, its frequency would remain fixed. If recorded onto the disc, its frequency would change in proportion to the difference in speed; the frequency did change, and we therefore concluded that the ringing was cut into the disc. Subsequent examination of the groove walls with an electron microscope confirmed our findings. This ringing is characteristic of the Westrex lathe system used in the production of CBS STR test records... The square-wave signal produced by the same cartridge using our Neumann SX 74 bidirectional exciter measuring system...shows no such ringing.

Also, in view of the construction quality, component selection and the sheer number of research hours in the development of the FET-10, the pricing does not begin to reflect the kind of profit margins which unfortunately typify esoteric audio products today. Considering that some moving coils cost $1000 to $1500, and adding to it the cost of a preamplifier up to $3000, we consider the price of the FET-10 and its accompanying source module with its own gain control to be a bargain, with sound quality superior to that of any front end on the market today.

Lastly , I wish to congratulate you on the comeback of your blunt and honest publication, and I would like to wish you every success.

Yours sincerely, Dr. Sao Zaw Win,

Win Research Group, Inc.

Goleta, CA

All our applicable comments are in the brief Win FET-10 follow-up under

"Analog Miscellany" in this issue, except those relating to the analog vs. digital controversy, which come up in nearly every one of our articles and columns. To be "blunt and honest," we believe you are wrong about the superiority of analog pho no technology to the best implementations of CD and DAT, although we admit that not very long ago you would have been right. See also our opening remarks in the current "Records & Recording" column.

-Ed.

Win FET-10 Channel Separation, Left/Right, in dB Measured with Seven Different Test Records and the Neumann SX 74 Bidirectional Exciter

-------

[adapted from TAC, Issue No. 12]

---------

Also see:

Various audio and high-fidelity magazines

Top of page