Part III of our series, in which we simplify (without compromise) our lateral and vertical tracking alignment instructions, clear up a few misunderstandings, and talk about some far from negligible new products.

Some of our readers haven't quite recovered from the shock of being told that nearly all tonearm mounting holes are drilled in the wrong place, nearly all headshells are offset at the wrong angle, and nearly all cartridges are mounted in the wrong position within the head shell. That these ridiculous errors should be permanently frozen in the design specs of tone arms and turntable/arm systems, as well as in tone arm manufacturers' mounting instructions, is something the average audiophile finds hard to swallow. Add to that the incorrect vertical tracking angle (VTA) designed into the majority of cartridges, and we begin to get re actions from "I don't believe it" to "I give up." Well, you had better believe it and you had better not give up, otherwise your $10,000 stereo system is a joke. No system, no matter how sophisticated, can correct the time-dispersive distortions introduced right at the stylus tip of an incorrectly aligned cartridge. And those distortions are readily audible, assorted Polly-annas and vested interests to the contrary not withstanding.

For the benefit of our new subscribers and of all those who found our original presentation of the subject (Volume 1, Numbers 1, 4 and 5) a bit more than they had bargained for, we want to restate our basic message as simply and inescapably as we can, at the same time making the alignment instructions somewhat more ob vious and palatable.

The playback stylus must mimic the cutter stylus.

As you undoubtedly know, a stereo groove is cut both laterally and vertically. The lateral motion of the cutter stylus, when the original lacquer master is made, always takes place along a radius of the record, i.e., the line passing through the stylus tip and the turntable spindle. That's inherent in the geometry of the cutter mechanism. The vertical motion of the cutter stylus is not perpendicular to the record, as you might think (and as would be simplest), but occurs at an angle that deviates from the perpendicular by 15 to 18.5 degrees in modern cutting practice. Now, the only way you can get the identical waveform out of the terminals of the playback cartridge as went into the terminals of the cutter head is to duplicate this lateral and vertical motion, without any angular errors, at the tip of the playback stylus. That's all there is to it.

If the lateral motion of the playback stylus is not exactly along a radius (lateral tracking error) and/or if its vertical motion is rot inclined at exactly the original cutting angle (vertical tracking error), the result is not only simple harmonic and IM distortion, as has been popularly assumed, but also frequency inter modulation (FIM) and frequency cross-modulation (FXM) distortion, which are time-dispersive and therefore much more audible and disturbing. The mathematical proof of this is 37 years old in the case of lateral tracking error and at least 15 years old for vertical tracking error (see the references in our original articles), so we're getting just a little tired of arguing about the inarguable with resisters of Mother Nature who haven't done their home work. (Some of them in surprisingly high places, we might add.) The point is that, when your reference signal is riddled with FIM and FXM distortion, you can't tell how good or bad the components are that you're listening to. Therefore, all subjective evaluations of audio equipment where phonograph records are the program source must be considered highly suspect unless the cartridge has been aligned within an inch (or rather 0.005 inch) of its life. And one way to make virtually certain that the cartridge is misaligned is to mount it dead straight and trued up in the headshell of a tone arm that in turn is mounted on the turntable according to the manufacturer's instructions (or even by the manufacturer). A quick check of your own arm and cartridge against the data presented below will confirm that outrageous statement- unless, of course, you're one of our regulars and have already performed the corrective alignments. Unfortunately, we're the only re viewers to keep harping on this subject, which may be one reason why we sometimes come to different conclusions than our colleagues, especially about cartridges and preamps. (Components such as speakers, headphones and power amps can also be evaluated with tapes, although we don't know of too many reviewers who use 30-IPS master tapes like ours, either.) The positive aspect of the matter is that a correctly located stylus will reveal unsuspected treasures in your record collection; suddenly you'll discover that a large percentage of 12 inch LP records, both old and new, sound quite excellent when the information in their grooves is extracted unaltered. In fact, the overall sonic improvement after a typical phono setup is brought into precise alignment is generally greater than what audiophiles expect, and get, when they switch from one good cartridge or preamplifier to another. Therefore, our final word of advice is: align before you switch.

(You've just saved yourself the equivalent of a lifetime subscription to The Audio Critic.) The basics of lateral tracking alignment.

There are only two kinds of tone arms capable of error-free lateral tracking and requiring no lateral alignment computation. One is the theoretically ideal straight-line tracking kind, exemplified by the Rabco variants and the Bang & Olufsen. Unfortunately, we've never run across one that was the equal of the best conventional arms in its solution to more mundane design problems, such as bearing play and arm tube resonances. (Of course, we haven't seen every one of the basement work shop mods.) The other is the pantograph-type arm, of which the Garrard tangent-tracking changer arm is the best-known current example. This somewhat awkward format is beset by its own peculiar demons (although we've seen a very promising execution by Win Laboratories, still in prototype form) and, unlike the straight-line tracking arms, still needs antiskating bias. It appears that the classic pivoted arm is here to stay for a while, as it has proven to be the most readily perfectible format, except for its inherent lateral tracking error-which is of course what we're trying to optimize here.

It's obvious that a rigid pivoted arm must swing in an arc and therefore can't possibly track radially. What's less obvious is the precise relationship between the resulting tracking error and the corrective offset/overhang geometry of typical arms. A prevalent mistake is to assume that it's the tracking error that must be minimized. Actually, it's the tracking distortion, which happens to be directly proportional to the tracking error but inversely proportional to the radial distance of the groove from the spindle. Consequently what must be minimized is the ratio of the tracking error to this radial distance. The correct way to formulate the basic mathematical question about optimum lateral tracking geometry is therefore the following: with a tone arm of given effective length, and over a total recorded area of given maximum and minimum radii, what combination of offset angle and overhang will yield the smallest possible peak values of the ratio of tracking error to groove radius? Not a seventh grade problem in geometry, that one, although any competent mathematician could give you the correct solution. No one bothered until 1941, when H.G. Baerwald did the job once and for all. Our table of alignments is based entirely on his definitive work, which should have eliminated forever (among other things) the untutored practice of jockeying for zero tracking error at the innermost groove, a la SME. Correct alignment results in two zero-error points, the first about one third of the way into the record ed area, the second close to but still a small distance away from the innermost groove. And with optimum offset angle and overhang, these zero-error points are fixed, regardless of arm length, as long as the maximum and minimum radii of the recorded area are specified. (For exact numerical values, see table.) The important thing to remember is that correct tone arm geometry is not a matter of opinion; for any given set of conditions there exists only one optimum solution, and all others are wrong. Unfortunately, the message hasn't reached the vast majority of tone arm designers yet, nor equipment reviewers for that matter.

The next arm or turntable/arm combination you buy is virtually certain to have incorrect geometry and/or mounting instructions, especially if what you're after is optimized playback of 12-inch LP records. (Some designers depart from optimum LP geometry to accommodate 45-RPM doughnut singles. Yechh.) On the sunny side, it must be emphasized that very few arms are so far off in their basic dimensions that minor corrective surgery can't bring them in line with our table of optimum alignments.

It's a fussy, unforgiving, time-consuming job, however, which we can't confidently recommend as a "first project" for the total novice even on the basis of the somewhat simplified (or at least more deliberately spoon-fed) instructions that follow. Above all, you must be thoroughly comfortable with elementary geometrical concepts such as parallel, perpendicular, right angle, zero degrees, radius, axis, etc., be fore attempting the alignments. As we've discovered, not all owners of $10,000 stereo systems meet that requirement. (We trust that all high-end dealers do; they're not doing their job if they won't help you with this sort of thing.) The procedure itself.

You begin by installing the cartridge in the tone arm. If the headshell has no slots in it, only a pair of screw holes, you're already in trouble;

you may have to enlarge the holes later. Never mind for the moment; just put in the screws and connect the cartridge leads. If there are slots in the headshell, don't push the cartridge all the way forward or backward; leave some room in the slots for making an eventual adjustment either way. Now tighten the screws just enough to seat the cartridge firmly, but not so much that you can't move it with a little pressure.

You're now ready to measure the effective length of the tone arm. This is defined as the perpendicular distance from the stylus tip to the lateral swing axis and must therefore be measured in a plane parallel to the record surface. The most convenient plane is generally (but not necessarily, in the case of oddball arms) the one in which the top of the headshell and the top of the arm tube lie. Try to locate the position of the stylus tip as seen from the top of the headshell. You may even want to mark a dot on the headshell with a fine-tipped felt pen.

(Sometimes, though, the stylus will stick out in front of the headshell. Then you'll just have to locate it with respect to the top of the cartridge itself.) Next, locate the exact axis around which the arm swings laterally. This will usually coincide with the central axis of the arm pillar, but (again) some arms can fool you visually. The center point of the top bearing or pivot will nearly always be a good visual reference. Once you have these two points unequivocally located, measure the distance between them. Try to be accurate within half a millimeter or so, but don't agonize over this measurement, as it happens to be the least critical in the entire alignment procedure.

Now look at the table of alignments. Find the optimum overhang corresponding to the effective arm length you've just measured. If the arm isn't mounted yet, the correct distance of the mounting hole from the turntable spindle is obviously the effective arm length minus the optimum overhang. Drill it exactly there, re gardless of where the arm manufacturer tells you to drill it. If the arm is already mounted in a hole drilled at an incorrect distance, your last hope is that the hole is large enough to allow some play or that the leeway you left in the headshell slots will be enough to correct the situation. In some cases the arm may have to be removed and a new hole drilled. (Please blame the perpetrator of the goof, not the bearer of the bad news.) Assuming that the arm is mounted correct ly, or almost correctly, you're ready to align the overhang. This must be done with the stylus tip, the turntable spindle and the lateral pivot center all in one straight line. If you can't swing the cartridge all the way over the spindle, loosen the arm pillar and twist it until you can. The overhang should be measured with a short, narrow and very accurate machinist's scale or ruler; if you measure the distance from the stylus tip to the perimeter of the spindle and then add the radius of the spindle (which is al ways 3.6 mm), you'll have no trouble getting an accurate overhang reading. Then you can gently prod the half-tightened cartridge into place so that you obtain the optimum overhang.

But don't tighten the screws all the way yet.

------------------------

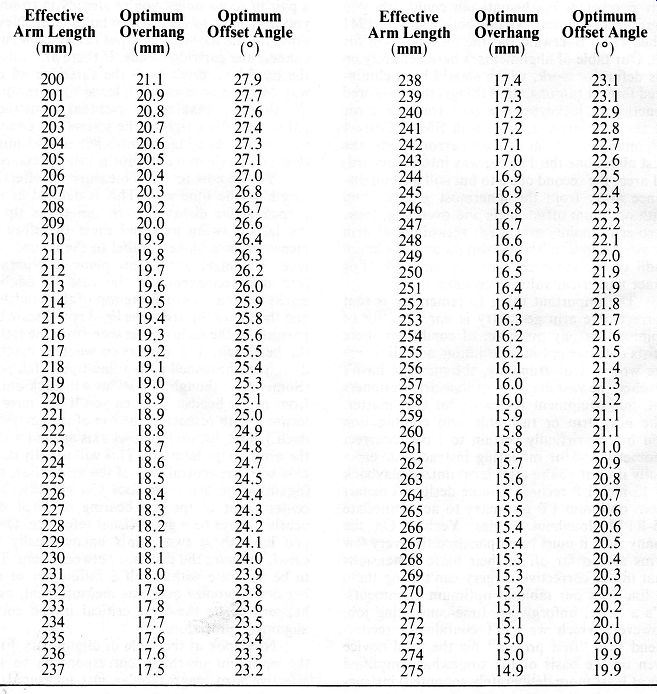

Optimized for a 30-cm LP record with a record ed area between the IEC Standard maximum and minimum radii of 146.05 and 60.325 mm.

Zero tracking error in all cases at radii of 120.9 mm and 66.0 mm. Optimum offset angles are specified for reference purposes only and are not involved in the recommended alignment technique. Please note that this is a simplified table, with decimal places rounded off beyond Effective Optimum

Optimum Arm Length

Overhang Offset Angle (mm) (mm).

Metric Table of Optimum Overhang and Offset Angle Alignments for Pivoted Tone Arms the highest expected measurement accuracy without specialized instruments. Also note that the product of the effective arm length and the sine of the optimum offset angle is a constant (93.4 mm). This corresponds to the length of the perpendicular from the lateral pivot point to the rearward extension of the long axis of the cartridge. For conversion to inches, use 1 mm = 0.03937 in or | in = 25.4 mm.

Effective Optimum

Optimum Arm Length

Overhang Offset Angle (mm) (mm) (°)

--------------------------------

Now comes the moment of truth. You must check the lateral tracking error at the two universal null points referred to above and set the error to zero, without changing the optimum overhang you've just obtained. For this you'll need an alignment protractor, which you can easily fabricate for yourself from an ordinary file card. Simply mark off three points on one of the printed lines anywhere near the middle of the card. From left to right, the second point should be 66.0 mm from the first and the third point 120.9 mm from the first (not from the second). Then punch a spindle hole of 7.2 mm diameter through the first point. If you wish, draw two perpendiculars to the printed line, intersecting it at the second and the third point; some people don't find this necessary. Slip this protractor over the turntable spindle and very gently lower the stylus over the 120.9 mm point.

The best thing is to poise the diamond just a hairsbreadth above the protractor by means of the cueing mechanism, so as to prevent possible damage through actual contact and slippage.

Now, determine whether the stylus bar is dead perpendicular to the printed line at the 120.9 mm point or, alternately, whether the front edge of the cartridge is dead parallel to the printed line when the stylus tip is on the 120.9 mm point. (The latter determination is possible only with perfectly rectangular cartridges, such as the Denon DL-103 series.) This is where most people begin to have trouble with the alignment procedure, since there are as many nagging little problems that arise as there are different cartridge bodies and headshell configurations.

We have no easy answers; various alignment tools have been suggested, none of which is commercially available; a small, thin mirror, scored with “cross hairs," is a possibility, but of course it must be accurately located. The best tool is a complete understanding of the basic geometry of the situation; the visual references will then suggest themselves.

If the lateral tracking error isn't zero at the 120.9 mm point, twist the cartridge in the head shell (i.e., point the stylus further inboard or outboard) until the error disappears. If you did this exactly right, the error will also be zero at the 66.0 mm point. Check carefully back and forth between the two points, making sure at the same time that you haven't changed the correct overhang in the process. If the cartridge can't be twisted in the headshell, you may have to switch to thinner mounting screws or, in extreme cases, enlarge the screw holes in the head shell with a file or drill. Be prepared to go through several cycles of alignment (optimum overhang vs. effective arm length, null points, twisting, etc.) until everything is perfectly trimmed in. That's when you finally tighten the screws all the way-but not so much that you shift the cartridge and undo all you've done.

And that's it; you've now optimized the lateral tracking geometry.

Antiskating bias adjustment.

As a necessary consequence of offset arm geometry, the friction of the moving groove against the stylus exerts a pulling force that is not in a straight line with the holdback force opposing it. The net result is an inward (i.e., spindle-ward) skating force, which must be canceled out in order to maintain equal forces on both groove walls and also to prevent tracking error from creeping right back in again. The next step in the alignments, therefore, is the application of correct antiskating bias.

A lot of incorrect information has been circulated on this subject. One of the recurrent assertions is that antiskating bias is impossible to set accurately, since the skating force varies with the location of the stylus on its way across the record and with the modulation level of the groove. That may very well be the case when either the lateral tracking geometry or the vertical tracking force is totally out of whack, but most emphatically not when they are properly trimmed in. With the tracking angle reasonably constant and the stylus firmly seated in the groove at all times, the frictional bias on the stylus, and therefore the skating force, will undergo no appreciable change from outer groove to inner groove and from quiet to loud passages, so that it can be effectively neutralized with an equal and opposite bias. The very alignment procedure that follows proves that point directly in situ.

First, set the vertical tracking force to the highest figure that's still within the cartridge manufacturer's recommendations. (Don't worry; when everything is properly aligned, your records are perfectly safe with the higher VTF and distortion is much lower.) Next, set the antiskating bias on the arm to correspond to the VTF you've just selected. (Who knows, the arm may even be calibrated accurately.) Now put a record with a quiet opening passage (i.e., barely visible wiggles in opening grooves) on the turntable and play that passage while looking at the cartridge and stylus from the front.

A hand-held magnifier of the right size can be helpful here. Since the side-to-side excursions of the stylus will be minimal, it should appear perfectly centered with correct antiskating bias.

To check perfect centering, raise the cartridge a few millimeters above the record and then lower it again. There should be absolutely no visible difference in centering either way. If there's the slightest sideways snap of the stylus as you raise it, there's either too little or too much antiskating bias applied and you must adjust it. When you're convinced that every thing is right on the button, try another quiet passage further in on the record. Lo and behold, the stylus remains perfectly centered and no further adjustment is required. On heavily recorded passages the centering is more difficult to verify by eye but will remain correct if you did the quiet-groove adjustment accurately.

Vertical tracking angle alignment.

Even after the lateral tracking geometry, vertical tracking force and antiskating bias are totally optimized, you ain't home free yet. The vertical tracking angle still needs to be trimmed in. What's more, it needs to be trimmed in over and over, whenever you change from one particular make of records to another, and even within the same make from older to more re cent releases. Again, don't cut off the head of the messenger who brings the bad news. We can't help it if the record industry has no VTA standard and every company is cutting records with their own version of the "best" angle. All we can tell you is that you must compensate for these VTA variations if you want to enjoy the sound of a correctly aligned phono system; in fact, without proper VTA alignment, the benefit of all the preceding alignments will be largely lost, at least in stereo.

The issue, then, isn't whether or not the VTA needs to be realigned with each record but how to do it with the least fuss and bother.

Fidelity Research (FR) has an excellent solution to the problem (see review below); their knurled-knob adjustment is almost as easy to set by ear as a tone control. FR arms that in corporate this feature are mind-bogglingly ex pensive, though, so that owners of plebeian Graces, Black Widows, Series 20's and the like will have to go through the following less convenient procedure.

Get a copy of one of the Mark Levinson Acoustic Recording Series albums. (The reason why we specify the brand is that MLAR records appear to be cut with a larger VTA than any other make we've run across. If you set your arm pillar height for the largest VTA you're likely to encounter, you'll need to mess only with the front end of the arm from there on.) Listen very carefully to this record while you vary the height adjustment of the arm pillar in the tiniest possible increments. Try to obtain the most incisive, most clearly etched highs short of actual edginess and the most transparent, least gargly or hooty midrange.

Generally speaking, you'll hear a wiry or edgy quality creep in as you go too high with the pillar and a somewhat muffled, gagged quality as you go too low; these aural guidelines are valid, however, only if you're already in the ball park, approaching the correct setting. A setting that isn't even close to right could sound like any thing at all-except right. Some cartridges are designed with a VTA so large that it's impossible to set the pillar low enough for correct compensation. Shimming the cartridge behind

the mounting screws so that the heel of the cartridge case almost touches the record is a desperate last measure that also fails in extreme cases. If you stick with our recommended moving-coil cartridges you won't run into this difficulty.

When you're convinced that the MLAR record sounds as clean and focused as it possibly can in your system, lock the arm pillar permanently with the height-adjustment screw or screws. Then round up the following paraphernalia: (1) the thinnest record you can find (one of the early RCA 'Dynaflex' jobs will do nicely); (2) a record of normal thickness; (3) the thickest record you can find (a really ancient mono LP ought to fill the bill); (4) a large card board strobe disc, or anything else that will fit on the turntable spindle and is a lot thinner than even the thinnest record. By using these, either singly or in combination, as shims under the record you're playing, you can generally achieve proper vertical tracking geometry for the range of VTA's encountered in modern records. Go through the same procedure and note on the jacket what kind of shimming each record sounds best with. Admittedly, a record under another record doesn't constitute the world's most stable and best-damped turntable mat. It's the lesser evil, though, compared to the wrong VTA. Our ears tell us so. Speaking of mats, you may have to remove yours for the initial arm height adjustment, otherwise you'll run out of vertical space with certain arms and/or spindles as you keep shimming. But then you can insert the mat as one of the principal shims for in-between VTA's. Be flexible and experiment freely; you've got nothing to lose but FIM and FXM distortion. Above all, don't check whether the cartridge or the arm tube is parallel to the record, the way it's illustrated in the instruction manual. It doesn't mean a damn thing.

By the way, the one alignment that all the instruction manuals insist on is by far the least important. This is the stylus azimuth alignment, making sure that the diamond shank is perpendicular to the record when viewed from the front. We aren't telling you to ignore this obvious requirement, but rest assured that, say, a 1° error in azimuth will degrade the signal considerably less than a similar error in lateral or vertical tracking alignment. Furthermore, if the right angles in the construction of the turn table, arm and cartridge are held reasonably close to 90°, there should be no need to worry about the azimuth to begin with. We've never had to fuss with it in the kind of equipment we deal with.

About our latest tests and reviews.

We still don't have an established, sequential laboratory test procedure for phono systems, such as we have evolved for speakers. We never had much faith in standard test records, except for identifying gross deficiencies; accelerometer measurements hold some promise, but we're just beginning to set up instrumentation to see if the results correlate with what we hear. Repeatable tests for mechanical and air borne feedback in turntables and arms are still in the earliest stages of development in the lab oratories of the few technologists who fully appreciate this decisive aspect of design; we're in the process of exploring the problem but have no quantified data to report yet.

Thus the reports that follow are based on purely qualitative technical criteria plus extensive listening tests. We'd like to be further along in our laboratory test program; on the other hand, we haven't seen any test or tests from other sources in which the obviously best sounding cartridges, for example, yield the obviously best measurements. We feel that we can at least distinguish between important and unimportant design characteristics, which is more than what we see in typical equipment reviews; and when it comes to listening, we have speakers and electronics of considerable resolving power to show up the real differences between the units under test. (For a detailed description, see the article on reference systems in this issue.)

------------------

ADC LMF-1

Audio Dynamics Corp., Pickett District Road, New Milford, CT 06776. LMF-1 low-mass carbon-fiber tone arm (with integrated headshell), $205. Tested sample on loan from owner.

This Japanese-made arm is correctly conceived in many respects but is disqualified from audio-purist status by that old bugaboo, wobbly bearings. As we've said before, this will in variably result in subtle time modulations of the signal to which the ear is extraordinarily sensitive. Tone arm bearings must never be al lowed to have more than one degree of freedom; we wish every tone arm designer could have a Breuer Dynamic in his hands just once and feel those Swiss bearings.

In addition, the offset angle of the LMF-1 is too small for 12-inch LP records, and the overhang specified in the mounting instructions is also too small. Thus, even though it doesn't suffer from incurable diseases, we can't recommend this arm in its current version.

Cotter B-1

Mitchell A. Cotter Co., Inc., 35 Beechwood Avenue, Mount Vernon, NY 10553. Turntable Base B-1, approx. $1300 (including dealer's charge for assembly and alignment but not including turntable or tone arm). Tested samples owned by The Audio Critic.

Mitch Cotter, whom we sometimes refer to as The Wizard of Oz ('because of the wonderful things he does' and other interesting similarities), is now making his highly specialized audio products under his own name instead of Verion's, for various legal reasons that need not concern us here. So start getting used to audio purist invocations of the Cotter rather than the Verion pickup transformer, the Cotter triaxial cables, etc., and now the monstrous and marvelous Cotter turntable base.

The B-1 is typical of this man's search for final solutions; it's the sort of thing that disposes of the problem in toto and won't have to be done again, except perhaps to make the product less prohibitive in price and cosmetically more appealing. The problem solved by the B-1 is the dirty little secret of all commercial turntables, including the best (even such as the Linn-Sondek LP12 and the Thorens TD 126): they're much too active acoustically. In a room filled with music at a level approaching live listening conditions, mechanical and airborne feedback through the turntable will generate signals in the cartridge that are only a little more than 20 dB below the program level un der the most favorable conditions, with the Linn or Thorens type of suspension. Under worst-case conditions, using large woofers and turntables with marginal or no suspension (a la Japanese direct drive), the spurious signals may be as little as 15 or even 10 dB down and in some cases may punch right through the pro gram level. All this without necessarily creating actual oscillation (feedback howl). Needless to say, we're talking about bass and lower midrange frequencies, not anything over 500 Hz or so. But don't those fantastic rumble figures, obtained in silent laboratories, seem rather meaningless under the circumstances? We estimate that the Cotter B-1 exceeds the typical isolation figures cited above by at least another 40 dB. The difference is phenomenal; the turntable survey in our next issue should include more precise figures but for the moment let's just say that the B-1 clarifies melodic bass and increases midrange transparency in comparison with any other turn table mounting system to a degree we weren't prepared for. No hairsplitting A-B-ing is required; you don't want to switch back to A after the B-1.

The main structure in the B-1 is a 23" by 17.5" by 1.5" thick plate made of laminations of steel and a special energy-absorbing plastic material. It appears to be the acoustically deadest object on the face of the earth; slap it hard and all you hear is the sound of your hand. (We don't advocate this as a scientific test.) Bolted to this base plate are the turntable motor pad and the arm pad, both of them similarly thick plates laminated from aluminum and energy absorbing plastic. The turntable must be partially disassembled and rewired to mount it on this contraption; it's no job for the novice. The entire system floats on large springs anchored in a heavy Formica-covered frame; the suspension resonance is in the neighborhood of 2 to 3 Hz. With the heavy Plexiglass cover mounted, the total weight is 135 to 140 pounds (61 to 632 kg) with typical turntables, arm not included.

It's a monster, rather "industrial" in appearance with the cover off, but quite accept able cosmetically with the cover in place.

Despite the lack of ultimate finish, the cost of parts and labor appears quite high.

So far, adaptations exist only for the Technics SP-10 Mk II and the Denon DP-6000 direct-drive turntables, although there's no reason why the B-1 could not be made to accept just about any high-quality turntable. We have used both the Technics and the Denon adaptations in our reference system and can re port that all of the mysterious ailments attributed by cultists to these essentially superior units are miraculously cured when they are separated from their inadequate factory bases and installed in the B-1. More about them, al so, in the forthcoming survey.

The main problem with the B-1 is its price.

Most people don't even think of the turntable base as an item to be considered in their audio budget, let alone as a four-figure purchase. At the moment, however, there's no device known to us that will do at a lower price what the B-1 does; the closest you can come to it is to play a top-quality turntable several rooms away from the speakers with a long cable between the pre amp and the power amp. It's just as good exercise as jogging, and you won't even miss the beginning of the music if the lead-in groove is long enough. Eventually, we're told, there will be a complete Cotter turntable, in which the base should be considerably more cost-effective because of the "systems" approach from the ground up and the elimination of dealer's labor charges. Corrective measures are always more expensive than correct design from the start.

Meanwhile, in turntable bases, the Cotter B-1 is audibly and unquestionably State of the Art.

Cotter B-2

Mitchell A. Cotter Co., Inc., 35 Beechwood Avenue, Mount Vernon, NY 10553. Turntable Isolation Plat form B-2, $150. Tested sample on loan from manufacturer.

This is a 16" by 20" laminated plate similar to, though not as thick as, the base plate of the Cotter B-1. It weighs 35 pounds (16 kg) and is suspended at its four corners on large springs.

That's all it is. What it does is to decouple any turntable placed on it from floor vibrations and other mechanically transmitted acoustic excitations. In other words, it accomplishes part of what the B-1 was designed for but doesn't do the complete job.

If you have a turntable that's not too "live" acoustically in its basic construction and materials, you might achieve quite excellent results just by putting it on top of the B-2. Organ bass will certainly be cleaner and you'll be able to dance the polka right next to the turntable with impunity. On the other hand, you won't experience the surprising increase in lower-mid range clarity made possible by the B-1's inherent deadness and total insensitivity to air borne excitation. But at least the B-2 is an isolation platform that really isolates, unlike those fake marble slabs on rubber feet that barely do.

Fidelity Research FR-1 Mk 3F

Fidelity Research of America, PO Box 5242, Ventura, CA 93003. FR-1 Mk 3F moving-coil stereo cartridge, $230. Tested #018639, on loan from distributor.

We hate to do this to you, but we like this moving-coil cartridge even better than the GAS 'Sleeping Beauty' Shibata, our previous top recommendation. We certainly didn't plan to have a new reference cartridge in every issue, but we have to call them as we see them. Be sides, the GAS has turned out to be rather variable, with some quite inferior samples floating around, whereas every FR-1 Mk 3F we've checked so far has been excellent. We must hasten to add that our preference is based on a perfect sample of one against a perfect sample of the other.

Specifically, the FR has even better resolution of inner detail, greater clarity on top, and more solidity in the middle and on the bottom than the GAS. Better tracing may be part of the reason why; the stylus geometry seems to be even more sophisticated than the Shibata con figuration. This is a fat stylus with a very narrow, long-line contact area; FR calls it a 0.3 by 3-mil tip (7.6 by 76 microns). Its lateral contour apparently doesn't permit it to bottom in the groove like a Shibata but the fine "edges" can really get around those high-velocity zigzags.

There are also other refinements inside the cartridge, including a unique magnet structure and a silver coil, no less. The F suffix stands for "flat," to distinguish this model from a predecessor with a rising high-frequency response that had to be equalized.

The overall sound of the FR-1 Mk 3F is impeccably clean, accurate, uncolored and musical. Through the Cotter (formerly Verion) transformer with 'P' strapping, it has become our reference cartridge.

Fidelity Research FR-64s and FR-66s Fidelity Research of America, PO Box 5242, Ventura, CA 93003. FR-64s dynamic-balance tone arm, 3600 (optional B-60 stabilizer, $450 extra). Tested #022176 (with #022388). FR-66s transcription-length dynamic-balance tone arm, $1250 (including B-60 stabilizer as standard equipment). Tested #022283.

All samples on loan from distributor.

These are extremely sophisticated and beautifully made arms, preferable in many ways even to the Breuer Dynamic, our previous top choice. The Breuer still has the most amazingly play-free and friction-free bearings we've ever seen, and we would still use it with ultra-compliant cartridges on account of its lower mass, but the FR bearings are also excel lent, and with the medium-compliance MC cartridges we favor the arm mass can be a little higher. Overall, the FR arms deserve to go to the head of the class on at least three counts: (1) they are quite a bit deader (less active acoustically) than the Breuer, eliminating that last little trace of lower-midrange coloration; (2) they are much less fragile and fussy than the Breuer, with the added flexibility of removable headshells; (3) the knurled-knob VTA adjustment referred to in our discussion above is a joy and a convenience no one in his right mind would want to give up after getting used to it.

The difference between the FR-64s and the FR-66s is merely one of length; the former is of the same order as other typical arms, whereas the latter is 62 mm longer from pivot to stylus.

Furthermore, the B-60 stabilizer, which attaches under the base and also incorporates the mechanism that raises and lowers the arm pillar for VTA adjustments, must be separately purchased for the FR-64s but comes as part of the FR-66s. Since the FR-66s also comes with an extra headshell ($54) and various other minor goodies, it turns out that the extra length costs only a little over $100 and is well worth that difference in terms of lower lateral tracking distortion if your turntable base is large enough. We suspect that the vast majority of our subscribers will have room only for the FR-64s. (The Cotter B-1 base, by the way, accommodates the FR-66s.) The arms are dynamically balanced, meaning that the vertical tracking force is applied by means of a spring after establishing zero balance by sliding the counterweight. This is by far the most stable method, also used in the Breuer Dynamic. Everything on the FR arms is well thought out, everything works perfectly (except that the cueing mechanism is overdamped, with annoyingly slow descent), and the sound with our favorite MC cartridges is the best we've ever heard. In some cases it may, however, be preferable to use a lighter headshell than the deluxe jobs that FR pro vides (such as, for example, the Supex SL-4).

And, always, we must keep coming back to that knurled knob on the B-60 attachment; can you imagine just gently twisting this knob and listening for the best sound, as if you were using a tone control, instead of fussing with the arm pillar, shimming up the record, etc., etc., to establish the correct VTA? Recent versions of the Breuer also have a similar adjustment, but (1) it's in an awkward location, (2) you need a screwdriver to use it, and (3) the main setscrew must be tightened after each change. It's not in the same class.

The lateral geometry of the FR arms is in the ball park but not right on the button, requiring just a bit of fiddling and twisting, not to mention ignoring the instructions. And the prices are insane, reflecting the weakness of the dollar against the yen (the arms are made in Japan) plus several large markups between the factory and the end user. But then what, or who, isn't insane in high-end audio?

Series 20 Model PA-1000

Series 20 (a division of Pioneer Electronic Corp.), 75 Oxford Drive, Moonachie, NJ 07074. Model PA-1000 carbon-fiber tonearm, $150. Tested sample on loan from manufacturer.

Series 20 is a name Pioneer made up to market certain high-end-oriented products in the United States without the handicap of the pop-hype image inherent in the Pioneer name.

As far as this neat little arm is concerned, all we can say is, "Now you're talking!" We distinctly prefer the PA-1000 to the Grace G-707, our previous ''best buy" recommendation. The carbon-fiber arm tube is better damped, the headshell is removable and also nicely damped, the bearings are at least as good if not better, and the overall construction of the arm appears to be superior. The sonic results bear out these mechanical considerations, and the arm is also convenient to install and to operate. What's more, the lateral geometry is close to being right on the nose, although you still have to ignore the mounting instructions.

If you're not sure you want to invest in something like an FR-64s or a Breuer Dynamic, a hesitancy we can't exactly reproach you for, you could do a lot worse than to opt for this excellent $150 arm. On any but the most excruciatingly accurate systems, you might not even hear the difference.

Series 20 Model PLC-590 (preview)

Series 20 (a division of Pioneer Electronic Corp.), 75 Oxford Drive, Moonachie, NJ 07074. Model PLC-590 direct-drive turntable, $550 with integral base and cover. Tested #XG13497T, on loan from manufacturer.

We're jumping the gun here on our more mainly because of our remarks about the Technics SP-10 Mk II and Denon DP-6000 direct-drive units in the Cotter B-1 review above. The PLC-590 is also a quartz-locked direct-drive system, with two important differences: (1) considerably lower price, despite the obviously high-quality construction and finish and (2) an inseparable base made of die cast aluminum, in which we discern at least an attempt to break out of the pattern set by other Japanese direct-drive designs and reduce acoustical activity to a reasonable level. The base is deader than most, though far from perfect in that respect; the so-called insulators it stands on (reminiscent of the Audio-Technica ATG605 accessory units) don't really bring the suspension resonance down to a low enough frequency to be completely effective but at least they aren't just little rubber pimples.

In other words, the PLC-590 is a step in the right direction. The Cotter B-2 platform could supply the mechanical feedback isolation that's lacking, so that the two could make beautiful organ music together and generally let the low frequencies rip at any volume level. All that and a gorgeous quartz-lock drive, too, for a total of $700. That's not a recommendation, just an idea. Tune in next time for more definitive information.

Signet MKIIIE

Signet Division, A.T.U.S., Inc., 33 Shiawassee Avenue, Fairlawn, OH 44313.

MKIIIE dual moving-coil stereo phono cartridge, $275. Tested sample on loan from manufacturer.

Just in case you figured we're suckers for any high-priced and late-model Japanese moving-coil cartridge, this one we don't really like.

The highs are much too hot and fatiguing, the rest of the range insufficiently open and focused.

In fact, the cartridge sounds not unlike certain middling magnetics. A second sample from an other source sounded similar, and one of our consultants had the same experience with a third sample. That closes the case as far as we're concerned, unless new information arises to reopen it.

Win Laboratories SDT-10 Type 11 (interim report)

Win Laboratories, Inc., PO Box 332, Goleta, CA 93017. SDT-10 Type II semiconductor disc transducer, $315 (including power source module). Tested samples on loan from manufacturer.

After three samples of this unique product, we're still in no position to give you the de tailed review we promised in our last issue. We won't bore you with the irrelevant details, but through no fault of our own or of Win Laboratories, something prevented us each time from testing the cartridge in depth. We trust that this statistically unlikely chain of events will come to a screeching halt, if we may mix our metaphors, and that we'll have a definitive report ready for the next issue. Mean while, just a few observations.

It's quite clear to us that Dr. Win has achieved a higher signal-to-noise ratio and a wider dynamic range than has so far been considered possible with strain-gauge cartridges.

He also makes the most beautifully crafted styli known to us; they make others look like muddy baseball bats under the microscope. The sound of the cartridge is either very good or better; what we can't tell you because of the difficulties we've had is just where we rate the SDT-10 Type II against the best MC cartridges. Our conservative recommendation would be that you stick with the latter unless you're on a very tight budget, in which case consider the following idea:

The power source module included in the price of the Win cartridge has sufficient output to drive any power amp. All you need is some kind of volume control in between. You could conceivably use two simple potentiometers in place of a preamp. We've always maintained that it's bad economy to save the small difference between the best cartridges and the cheapies, but saving the cost of a whole pre amp is another matter. Again, this is not an outright recommendation, just something to think about. Because no matter what final rating we'll end up giving the Win cartridge, bad it is certainly not.

Recommendations

There's an almost complete turnover here since the last issue, indicating the increasing awareness by equipment designers of the realities of accurate phono playback. We caution you, however, to read all reviews and sum maries to arrive at the most intelligent choice for your specific needs.

Best phono cartridge tested so far, regardless of price: Fidelity Research FR-1 Mk 3F.

Best cartridge per dollar: forget it (it's poor economy to save $100 or so on this all-important component).

Best tone arm tested so far, regardless of price: Fidelity Research FR-66s (if you have the room for it) or Fidelity Research FR-64s with B 60 stabilizer.

Best tone arm per dollar: Series 20 Model PA-1000.

Best turntable tested so far, regardless of price: Cotter B-1 system with specially adapted Technics SP-10 Mk II or Denon DP-6000 (fine tuned choice between the two in next issue).

Best turntable per dollar: Kenwood KD 500.

Cartridge/Arm/ Turntable--Summaries and Updates

All of the following reviews appeared in Volume I, Numbers 4 and 5.

Breuer Dynamic SA

Sumiko Incorporated, PO Box 5046, Berkeley, CA 94705.

Breuer Dynamic Type 5A tone-arm, $1250 (including Type 5C fluid-damping option).

An arm made like an expensive Swiss watch, with the world's finest bearings in the four-point gimbals suspension.

Outstanding performance, but the Fidelity Research FR-64s and FR-66s are considerably less fussy and fragile, much more convenient to use, and do an even better job in most installations.

Denon DL-103D American Audioport, Inc., 1407 N. Providence Road, Columbia, MO 65201. Denon DL-103D moving-coil cartridge, 3267.

A superior moving-coil cartridge of highly consistent quality, but not quite as smooth on top as the best samples of the GAS 'Sleeping Beauty' Shibata, nor quite as convincingly clear and detailed as the Fidelity Research FR-1 Mk 3F, our top choice.

Dual CS721

United Audio, 120 South Columbus Avenue, Mount Vernon, NY 10553. Dual CS721 automatic single-play turntable, $400.

The turntable is quite good, the arm even better, but if you don't need the automatic feature, the Kenwood KD-500 with the Series 20 Model PA-1000 arm will give you greater precision and acoustically deader construction for less money.

Dynavector 20B

Dynavector, 9613 Oates Drive, Sacramento, CA 95827. Dynavector 20B moving-coil cartridge (with beryllium cantilever), $250.

Made by Onlife Research in Japan, this moving-coil cartridge has sufficient output to require no matching transformer or head amp. Unfortunately, the built-in VTA is so large that corrective alignment is impossible, and the sound is unbearably steely and irritating. We haven't tested the 20C, which is a $350 low-output version.

Dynavector DV-505

Dynavector, 9613 Oates Drive, Sacramento, CA 95827. Dynavector DV-505 tone arm, $600.

An interesting attempt to reduce spurious acoustical activity through sheer mass, but a basically erroneous design. Ac curate resolution of lateral and vertical information in the groove is made impossible by the gross difference between the arm's lateral and vertical motional impedances. Extreme susceptibility to warp wow is another design flaw, and early samples of the arm suffered from mechanical play that destabilized the overhang alignment. We don't know whether this defect has been corrected.

EMT Model XSD 15

Gotham Audio Corporation, 741 Washington Street, New York, NY 10014.

EMT Model XSD 15 moving-coil cartridge, $420.

Inherently, one of the finest moving-coil designs of all time, but severely limited in tracing ability by the 15-micron spherical stylus. No other stylus is offered, except in oddball private adaptations. The integrated plug-in headshell prevents optimum lateral alignment in incorrectly offset tone arms; this too is removed by some private experimenters. With a modern "line contact" stylus and a standard body, the XSD 15 would still be a SOTA contender.

GAS 'Sleeping Beauty' Shibata

The Great American Sound Co., Inc., 20940 Lassen Street, Chatsworth, CA 91311. 'Sleeping Beauty' Shibata moving-coil cartridge, $240.

Second only to the Fidelity Research FR-1 Mk 3F in clarity and inner detail. Extremely smooth on top. But watch out! We've come across quite a number of substandard samples; the elastomer in the stylus suspension may not be permanently stable in some cases. Defective samples sound pinched, unpleasant and fatiguing.

Grace G-707, G-840F, G-940

Sumiko Incorporated, PO Box 5046, Berkeley, CA 94705. Grace G 707, G-840F and G-940 tone arms: no longer available in the versions reviewed.

The current list of available Grace models includes only one whose number indicates any continuity with those we reviewed; this is the G-707 Mk II, which now incorporates a compliance between the counterweight and the arm tube. We can't endorse this without a retest; as far as the old G-707 is concerned, it has been superseded as our "best buy" choice by the Series 20 Model PA-1000 (see review above).

Grado Signature Model II

Joseph Grado Signature Products, 4614 Seventh Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11220. Signature Model II stereo/CD-4 cartridge, $500.

Silk-smooth, grainless, non-fatiguing, extremely agreeable to the ear, but somewhat opaque in the midrange and lacking in accurate spatial detail in comparison with super-clear MC cartridges such as the FR-1 Mk 3F or 'Sleeping Beauty' Shibata.

The VTA is almost too large (maybe altogether too large) for corrective alignment and the stylus isn't of the optimal "line contact" configuration. Those two perversities aside, this may be very, very close to the ultimate possibilities of the inherently limited "moving field" principle. The Signature I11, which did not arrive in time to be reviewed in this issue, is a still further refinement of the same design, not a totally different creature.

Harman Kardon Rabco ST-7

Harman Kardon, 55 Ames Court, Plainview, NY 11803.Rabco ST-7 straight-line tracking turntable: no longer available in the version reviewed.

The jerry-built ST-7 has been replaced by the ST-8, a $499 model we haven't tested so far. Whether or not the impossibly loose and wobbly arm carriage, a disqualifying defect in the ST 7, has been corrected we have no idea. (Our curiosity isn't killing us, we might add. Straight-line tracking is the only 100% correct phono playback principle, but it doesn't readily lend itself to popularly priced executions.) Infinity 'Black Widow' Infinity Systems, Inc., 7930 Deering Avenue, Canoga Park, CA 91304.

'Black Widow' tonearm: no longer available in the version reviewed.

The Japanese-made 'Black Widow' now comes in the GF (graphite fiber) version at $245, which we haven't tested. The change is most probably for the better, since the original model had a somewhat live arm tube. Whether or not the bearing jitter we had found was also corrected we don't know. In any event, the considerably lower-priced Series 20 Model PA-1000, also a carbon-fiber model, looks like the best of the staple Japanese arms to us.

JVC MC-1

JVC America Company, Division of US JVC Corp., 58-75 Queens Midtown Expressway, Maspeth, NY 11378. MC-1 direct-couple type moving-coil cartridge, $300.

This is a radically different approach to moving-coil design, and we were quite excited about the fabulous midrange clarity we heard on a very early sample. Our enthusiasm was considerably dampened by an irritating high-frequency coloration we also heard. Now that the MC-1 is about to become available in U.S. stores, we're keeping our fingers crossed that JVC has fixed this disqualifying defect in their production series. If so, the MC-1 may turn out to be SOTA. If not, forget 1t.

Kenwood KD-500 Kenwood, PO Box 6213, Carson, CA 90749. K D-500 direct-drive turn table, approx. $200.

This could be described as a cheaper execution of the Series 20 Model PLC-590 approach. Direct drive (without quartz lock, of course), "resin concrete' chassis to achieve at least a modicum of acoustical deadening, not much isolation from mechanical feedback, good but not great quality overall.

Considering its imperfections, it works remarkably well. For the money, we don't know of anything better or even as good.

Linn-Sondek LP12 Audiophile Systems, 5750 Rymark Court, Indianapolis, IN 46250.

Linn-Sondek LPI12 transcription turntable, $549.

One speed only (33 1/3 RPM), no speed adjustment, not much torque, some very cheap-looking parts, but beautifully engineered platter and drive mechanism. Suspension and isolation about as good as on the Thorens TD 126 Mk II, with minor exceptions; audible performance definitely as good. The distributor discovered after we had returned our test sample that the bearing housing wasn't filled with oil and claims that the LP12 would have blown away the Thorens sonically had it not been for this oversight. We don't believe that the slight additional friction could have affected the signal in any significant way, but a retest has been scheduled and will be reported on in the next issue.

Luxman PD-121

Lux Audio of America, Ltd., 160 Dupont Street, Plainview, NY 11803. Model PD-121 direct-drive turntable, 3545.

This is no longer the top of the Luxman line; they have some expensive new goodies that may or may not have the same disqualifying defect as the beautifully made PD-121. That defect is either mechanically or acoustically excited drumming (thump, thump) of the large, flat base to which the turntable is permanently wedded. There's no cure for the drumming, nor for the thick, woofy sonic coloration it causes. A suggested bumper sticker for Japanese turntable designers: "The only good turntable is a dead turntable."

Mayware Formula 4

Mayware, England, distributed in the U.S.A. by Polk Audio, 1205 South Carey Street, Baltimore, MD 21230.

Formula 4 PLS4/D tonearm: no longer available in the version reviewed.

The original version we reviewed was not nearly as stable and dead as we would have liked. The new Formula 4 Mk III PLS4/D1 at $180 is still basically the same silicone-damped unipivot design, a format we feel has certain theoretical and practical shortcomings. Just how the new version performs as com pared to the old we don't know.

RAM 9210SG

RAM Audio Systems, Inc., 17 Jansen Street, Danbury, CT 06810. RAM 9210SG Semiconductor Phono Transducer System, 3299.

An adaptation of the old Matsushita (Panasonic) EPC 451C strain-gauge cartridge, now obsoleted by the more advanced strain-gauge technology of Win Laboratories.

SAEC WE-308N

Audio Engineering Corp., Tokyo, Japan. Distributed in the U.S.A. by Audio Source, 1185 Chess Drive, Foster City, CA 94404. SAEC WE 308N double-knife-edge tone arm, $195 when reviewed (latest price NA).

This is a very interesting case because the offset angle of this beautifully made arm is so insanely small that it's almost impossible (and in some cases actually impossible) to align the cartridge in its headshell for optimum lateral geometry. Yet, according to the distributor, its designers insist that they are right and we are dead wrong about tracking error. We were supposed to receive their complete exegesis of this theory but haven't so far. (Ahem, ahem.) The arm is also a bit on the massive side for nearly all cartridges, so you might as well relax and forget about it.

Thorens TD 126 Mk IIB Elpa Marketing Industries, Inc., Thorens and Atlantic Avenues, New Hyde Park, NY 11040. Thorens TD 126 Mk IIB electronic turntable, $500 (without tone arm) when reviewed. (May no longer be available in this version.) Currently we see a Mk III listed and that only in the C ver sion, complete with Thorens Isotrack arm, at $750. It's the same turntable, though, and a very good one indeed. The suspension and isolation are of the same principle as in the Linn-Sondek LPI12 and the results are at least as good if not better. Heavy footsteps and other subsonic excitations certainly disturb it less; the audible performance is indistinguishable from the Linn's to our ear. The TD 126 offers the added convenience of three speeds, electronically regulated, and the overall construction is very nice, although we like the Linn platter and drive mechanism even better. Until we discovered the Cotter B-1 system, this was our reference turntable, though without any deep religious conviction.

---------

[adapted from TAC]

---------

Also see:

Box 392: Letters to the Editor

Various audio and high-fidelity magazines

Top of page