Manufacturer's Specifications

Frequency Response: 25 Hz to 16 kHz. to 18 kHz with metal tape.

Harmonic Distortion: 0.8% at 0 VU.

Signal/Noise Ratio: 67 dB with Dolby NR.

Input Sensitivity: Mike, 0.25 mV; line, 77.5 mV.

Output Level: Line, 390 mV; headphone, 50 mV to 8 ohms.

Flutter: 0.04% wtd. rms.

Wind Times: 90 seconds for C-60.

Dimensions: 17-5/16 in. (440 mm) W x 4-13/16 in. (123 mm) H x 14-11/16 in. (373 mm) D. Weight: 15.2 lbs. (6.9 kg).

Price: $400.00.

------------

The Kenwood KX-900 cassette deck offers a number of features based upon its built-in RAM (random-access memory) microprocessor and logic-controlled drive system. The eject, power on/off, and timer (record/off/play) switches are at the very left of the front panel, and the light-touch, logic controlled transport switches are at the far right. This separation from the cassette compartment, next to the eject button, is not common, but there is no disadvantage to the user-it might even be better for the right-handed. The switches have large touch plates, making for very easy actuation, and there are status lights for each function with the exception of fast winds.

When the RAM switch is set to Counter M. (Memory) Index, pushing Play and the appropriate wind bar simultaneously will secure a fast wind to counter zero and then an immediate switch into play mode. If Stop is used with a wind bar, that function is obtained when zero is reached. If the RAM switch is in Search, the action is similar, but the stop/play occurs at the beginning (rewind) or end (fast forward) of the piece being played. If Rec Mute is pushed just momentarily while recording, recording continues without the signal for five seconds. The pause indicator flashes and stays on at the end of the period, at which point the deck switches to record/pause. If longer muting is needed, Rec Mute is held in for that time, but there is no automatic pause at the end. Recording can be initiated with a push of just Rec, and a flying-start recording also requires only Rec.

All of these transport/recording conveniences will certainly benefit many. Obtaining record mode with Rec only, however, could lead to inadvertent errors from a straying digit.

When the RAM switch is set to Memory, the deck is readied for programming for automatic playback of up to 15 selections in any desired order. The LED-type memory display shows single digits up to "9" and a dot and digit for 10 and above: '"5" for 15, for example. The selection number is stepped for insertion by the Program button and entered with the Memory button. Memory Call displays, in order, the number of all selections programmed. Any false entry can be removed with Clear. Along the same row as these buttons are the bias-adjust pot with a helpful center detent, the tape-select switch (CrO2, FeCr, Normal, Metal), the Dolby NR switch (Off, On, Filter Off), and the dual-concentric record-level pots. The knobs on the switches and pots are on the small side, which makes turning somewhat difficult.

The designations are silver on a dark background, and good illumination is needed for easy reading. At the top of the panel is a light-green Dolby NR status indicator, rather out of the way and low in intensity to catch the user's attention. On the other hand, the fluorescent bar-graph meters are very bright, easily read under any lighting condition. At zero and above, the segments are red-orange, calling attention to the possibility of distortion. At "-1" and above, there is a short-time peak hold, which is an additional plus for these peak-responding meters.

Jacks for headphones and left and right microphone inputs are at the bottom right of the panel, with the mike/line selector switch just above. The line in/out phono jacks are on the rear panel.

An examination of the internal construction of the Kenwood deck showed excellent soldering on the p.c. boards with interconnections made primarily with wirewrap and multi-pin cables. There were labels for the various adjustments, and all of the parts were identified. Of particular interest was the two-motor drive with a good-size flywheel.

Measurements

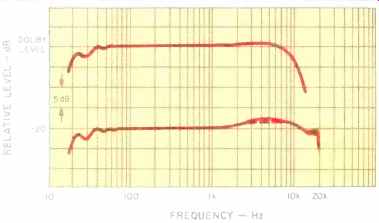

Fig. 1-Frequency responses with BASF Professional I tape with and without

(---) Dolby B NR.

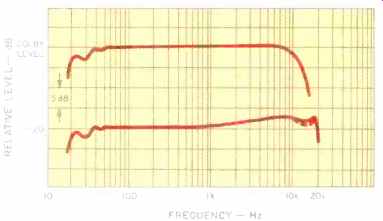

Fig. 2-Frequency responses with Maxell XL II-S tape with and without (---)

Dolby B NR.

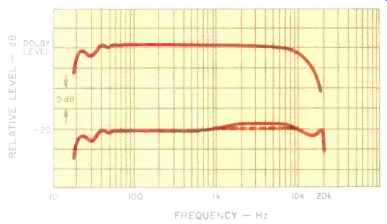

Fig. 3-Frequency responses with TDK MA-R tape with and without (---) Dolby

B NR.

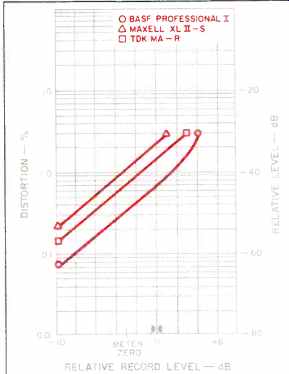

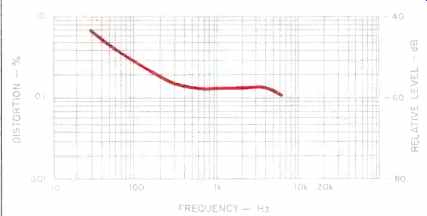

Fig. 4 Third harmonic distortion vs. level at 1 kHz with Dolby B NR.

Fig. 5-Third harmonic distortion vs. frequency with Dolby B NR at 10 dB below

Dolby level with TDK MA-R tape.

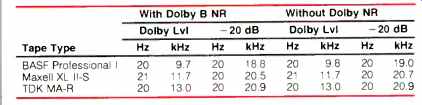

Table I-Record/playback responses (-3 dB limits).

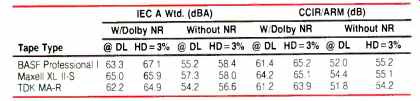

Table II-Signal/noise ratios with IEC A and CCIR/ARM weightings.

At first check, there was a large high-end roll-off in the playback of a test tape. Adjustment of head alignment gained the satisfactory result of all points within 2 dB of standard at both equalizations. This emphasizes the possible need for alignment after the shipment of any recorder.

Play speed was on the high side, 1.3% fast, and play-level indications were slightly high. The record/playback responses were given a quick look with pink noise and the 1/3 octave RTA. In general, the best results were obtained with bias adjust set close to the recommendations in the owner's manual. A large number of tapes were matched very well, and BASF Professional I, Maxell XL II-S and TDK MA-R were selected for the detailed testing. (Especially good matching was also found with Sony SHF, TDK SA, Sony FeCr, and most of the metal tapes. TDK SA-X, on the other hand, seemed to need more bias than could be set.) The swept record/playback responses were run both with and without Dolby B NR, at Dolby level and 20 dB below that. The plotted results for the three tapes are shown in Figs. 1 to 3, and the 3-dB down points are listed in Table I. All of the responses are quite good and superior to the specifications. The flatness at Dolby level is certainly worthy of note. In most cases, there was a rise in the response between 2 and 10 kHz, reaching 2 dB or over with both the Type I and II tapes. Increased bias would have brought this hump down with greater reduction in level at the highest frequencies, such as in Fig. 3. The phase jitter of a 10-kHz tone in playback was 25°, fairly good. The output polarity was the same as the input during recording, but was reversed in playback. Bias in the output during recording was very low. With XL II-S tape, the bias control had a ±4 dB range at 10 kHz. The multiplex filter was down 3 dB at 15.8 kHz and 37.2 dB at 19.0 kHz, excellent attenuation. Erasure of 100 Hz with metal tape was 60 dB, a very good figure.

Separation and crosstalk at 1 kHz were 57 dB and over 80 dB down, respectively, both outstanding results.

The third harmonic distortion was measured with the three tapes from 10 dB below Dolby level to the points where HDL3 = 3% while in Dolby mode. Figure 4 depicts the results, which are excellent for the Type I BASF Professional I but less so for the other tapes. Signal-to-noise ratios referenced to both Dolby level and the 3% points shown are listed in Table II. The figures are really very good, but the lower values for the Type II and IV tapes reflect the higher distortion levels evidenced in Fig. 4. HDL3 was also measured as a function of frequency at-10 dB from 30 Hz to 5 kHz with Dolby NR and TDK MA-R tape. The distortion is fairly low in mid-band, and the rise at the low end is moderate. At 5 kHz and above, the distortion level was dropping-unusual, and much better than the typical deck.

Input sensitivities were 0.19 mV for mike and 74 mV for line. The mike input overload point was a rather low 13 mV, first evidenced with flattening of the positive peaks. The input overload for line, in contrast, was more than high enough: Somewhere over 22 V. The line input impedance was 41 kilohms at 1 kHz with the input pots at mid-position.

Output clipping appeared at a level equivalent to + 14 dB relative to meter zero. The line output was 390 mV at meter zero, dropping to 320 mV with a 10-kilohm load-indicative of a source impedance of 2.12 kilohms. The headphone output was 47 mV to 8 ohms. There was adequate volume with all of the headphones tried, except perhaps for high-level freaks. The level meters had a very fast response, reaching zero with a 5-mS burst. Decay time for 20 dB was 0.5 S, also on the fast side. The bar graphs consist of 12 segments each, from "-20" to "+8." Calibration of each of the steps was excellent, with those from "10" to "+8" within ±0.2 dB, one of the most accurate seen to date.

Tape play speed varied 0.02% at most with time, and there was substantially no change with other line voltages.

Flutter was consistent from one end of a cassette to the other and from one tape brand to another, but it was on the high side. Typical values were-±-0.14% weighted peak and ±0.09% weighted rms. Wind times were 85 seconds for a C-60 cassette, logic-transport response times were about 1 second, and run-out to stop was 2 seconds.

Use and Listening Tests

Tape loading was a simple drop-in-and-push operation. Access for maintenance was excellent with the clear door cover removed. All controls and switches were completely reliable throughout the testing, but it was a little frustrating at times trying to check settings if room lighting was dim.

Considerable advantage was taken of the various search and memory features, including RAM. Timer start in record or play was just fine, with a three-second delay after turn on. Rec Mute seemed to have the just-right approach: Automatic muting and stop (record-pause) for RAM use, or longer mutes by holding the button. The convenience of going into record with just one button was quite obvious, but I remained skeptical because of the error possibilities mentioned earlier.

The fluorescent bar-graph meters were very easy to read with any room lighting because of their brightness and excellent action. The peak holds of about one second were extra helpful with the slightly fast decay. Record levels were set very quickly as desired, although there was a little fussing because of the small knobs on the dual-concentric record-level pots. The bias adjust was an essential part of the matching to many different tapes. The instruction manual was well written, with lucid text on RAM and memory functions. Illustrations were well done and pertinent to the text, and the list of reference (deck setup) and recommended tapes is most desirable and helpful in a cassette deck instruction manual.

Listening tests included pink noise and discs for sources. Among the records were the dbx-encoded version of Chalfont's The Empire Strikes Back and Mobile Fidelity's recording of Holst's The Planets with Solti and the London Philharmonic. In all cases, the metering aided recording in obtaining good levels without evident distortion. The metal tape showed the least sensitivity to overload distress. There was a slight shift in the sound balance from the original; sometimes it seemed to be a case of more presence--different, but not negative in character. Pause and stop sounds were slightly out of tape noise.

The Kenwood KX-900 has a number of features providing convenience for the user, and these, when combined with its performance level, represent good value when compared to other decks in the same price range.

-Howard A. Roberson

(Audio magazine, Jun. 1982)

Also see:

Kenwood KX-660HX Cassette Deck (Equip. Profile; April 1988)

Kenwood Spectrum 70 (One Brand System) (Jul. 1982)

JVC Model KD-85 Stereo Cassette Deck (Nov. 1978)

Kenwood DP-11008 Compact Disc Player (Jan. 1985)

= = = =