Manufacturer's Specifications:

Frequency Response: 2 Hz to 20 kHz, ±0.2 dB. THD: 0.0015% at 1 kHz.

Dynamic Range: 100 dB or greater.

S/N Ratio: 118 dB at 1 kHz.

Separation: 110 dB at 1 kHz.

Wow and Flutter: Below measurable limits (±0.001% wtd. peak).

Analog Output Levels: Fixed, 2.0 V rms balanced and unbalanced; variable, 2.0 V rms maximum.

Digital Output Format: AES/EBU digital audio interface.

Digital Output Levels: Coaxial, 0.5 V peak to peak. 75 ohms; optical, 12 dBm at a wavelength of 650 nm.

Number of Programmable Selections: 20.

Power Requirements: 120 V, 50/ 60 Hz. 32 watts.

Dimensions: 17 1/16 in. W x 55/16 in. H x 15 3/8 in. D (43.4 cm x 13.5 cm x 39 cm).

Weight: 41.8 lbs. (19 kg).

Price: $1,500.

Company Address: 222 New Rd., Parsippany, N.J. 07054, USA.

This top-of-the-line CD player incorporates several of Denon's technological advances, not the least of which is 20-bit, digital-to-analog conversion. Why, you might ask, would anyone employ 20-bit D/A conversion in a CD player when Compact Discs themselves contain data in 16-bit format? Denon provides some of the answers in one of their technical tutorials.

"If it were possible to make a perfect 16-bit D/A converter, 20-bit converters would have essentially no benefit. But real world considerations limit the performance of D/A converters. The additional precision offered by additional bits means that we can more closely approximate the work of a perfect 16-bit D/A. Considered in the abstract. 20-bit conversion can discriminate levels 16 times smaller than 16-bit conversion." The chief benefit of 20-bit conversion, if properly executed, is to reduce the player's contribution to quantization noise, which is the difference between the original analog values and their digital approximations. To fully realize the benefits of D/A conversion, Denon also uses a 20-bit digital filter. This filter features 110-dB rejection of out-of-band noise and. according to Denon, pass-band ripple held to ±0.00005 dB. As was true o' some previous Denon players, the output for the most significant bit (MSB) is hand-trimmed for more accurate D/A conversion. In the DCD-3520, they've gone farther and have adjusted the second-, third-, and fourth most significant bits. Tuffs accounts, in part, for the extremely high signal-to-noise ratio achieved by this model. Denon's unique approach to D/A conversion has been dubbed "Delta" by the manufacturer. Other notable refinements of the DCD-3520 include separate power transformers for the digital and analog sections and a double-isolated laser pickup transport. The unit has a copper-plated chassis with a four layer bottom plate, glass-epoxy p.c. boards, a second coaxial digital output, and balanced XLR-connector analog outputs.

As for operational features, specific tracks can be accessed directly, as can specific time into a given track. The usual search modes are available, including audible fast search in either direction. Up to 20 selections can be programmed in any order for playback, and programming will be retained in memory for about two days, even if power to the player is turned off after programming. A "Call" button on the supplied remote control will bring up track numbers in the order in which they are programmed. It is possible to have play begin at a specified index number within a given track. Repeat play of a single track, an entire program, or the entire disc is possible. A particular section of a track can be played by specifying start and stop times. The use of an external timer to start and stop playback is also feasible.

Control Layout

Only a few major controls and a large digital display area are visible when the hinged panel along the lower part of the front panel is in its closed position. The major controls include a power switch, the disc drawer open/close button, buttons for manual forward and reverse search, automatic forward and reverse skip, "Play," "Pause," and "Stop," and a button that opens the lower hinged panel.

Behind the panel are an "Index" button and a "Time" button. The latter changes the time display from the current track's elapsed time, to the time remaining on that track, to the total time remaining on the disc. Also behind the panel are a programming button, number buttons for specifying tracks--including a "+ 10" button for selecting track numbers higher than 10--and a "Display" button that enables you to turn off some or all indicators in the display area. A headphone jack, line-output level control, and a digital output selection/defeat switch complete the panel layout.

The supplied remote control duplicates most of the front panel's functions and adds a couple novel features of its own. One of these is called "Auto Edit." Press the button so labeled, and the player automatically divides the CD into two time periods, each approximately half the playing time of the disc. The preliminary owner's manual offered no practical reason for this feature, but I suspect that the thinking had to do with dubbing from a CD to a cassette, when there is more than 45 minutes on a CD (as is true of the majority of CDs released). Volume up and down buttons, when pressed, cause a motor to turn the front-panel volume control. Another button, labeled "Auto Space," inserts 4-S blank spaces between tracks, which is useful for dubbing to cassettes if your tape deck features automatic seeking of subsequent tracks. A "Time Search" button can be used to locate and play a passage by track number and time within a track (both start and end points can be set) or to set the start and end points for a repeated passage. There is also a "Clear" button that can be used to correct a programmed track setting if you make an error.

Measurements

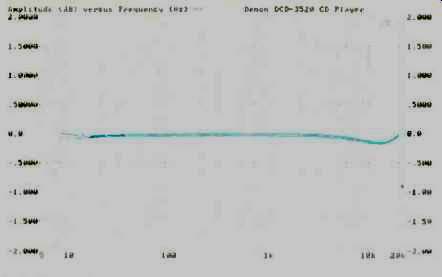

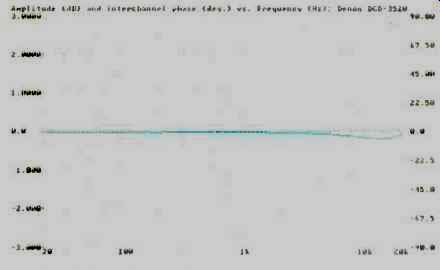

Other than a very slight dip in response of no more than 0.18 dB at around 13 or 14 kHz, frequency response (Fig. 1) was extremely flat from below 10 Hz to 20 kHz. The output level difference between channels was negligible. In a second sweep of frequency versus amplitude, I compared the phase of the left channel with that of the right channel at every audio frequency and observed no significant phase difference. Results are shown by the dashed curve of Fig. 2. (The solid curve is simply a repeat of frequency response of the left channel, for reference purposes.)

Fig. 1-Frequency response; note that trace begins at 7 Hz. Lower trace is

right-channel output.

Fig. 2-Interchannel phase difference (dashed curve) and amplitude response

(solid curve). Phase difference, in degrees, can be read from right-hand

scale.

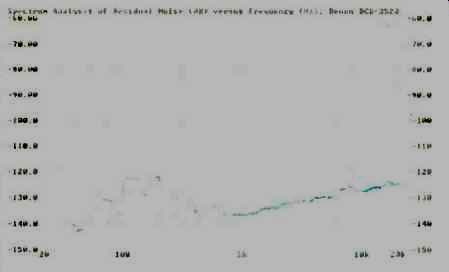

Fig. 3--Residual noise vs. frequency of left channel (solid curve) and right

channel (dashed curve) for "quiet" track of CD-1 test disc.

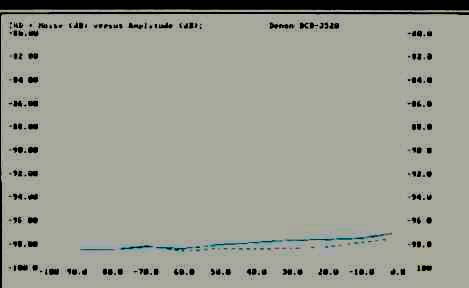

Fig. 4--THD + N vs. signal level for left channel (solid curve) and right

channel (dashed curve). The rise in distortion at 0 dB is almost imperceptible;

see text.

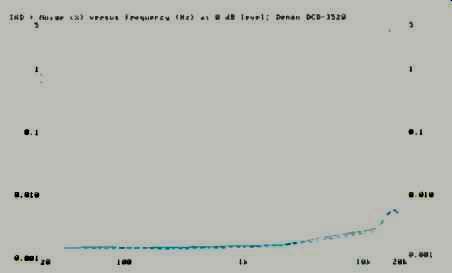

Fig. 5--THD + N vs. frequency at 0-dB recorded level for left channel (solid

curve) and right channel (dashed curve). The rise in distortion above 15

kHz is unusually small.

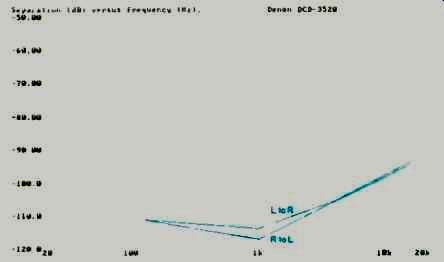

Fig. 6--Interchannel separation.

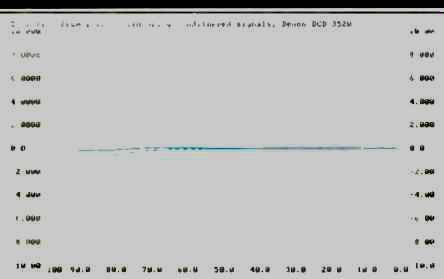

Fig. 7--Deviation from perfect linearity for undithered, 1-kHz signal was

virtually nonexistent in the left channel (solid curve) and only 1.7 dB at-90

dB signal level for the right channel (dashed curve).

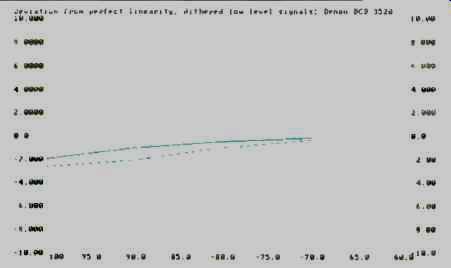

Fig. 8--Deviation from perfect linearity for dithered signal was only about

2 dB at-100 dB signal level for the left channel (solid curve) and only slightly

greater for the right channel (dashed curve).

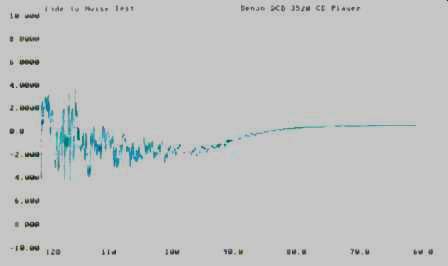

Fig. 9--Linearity deviation for EIA "fade-to-noise" test showed

dynamic range to be just over 105 dB.

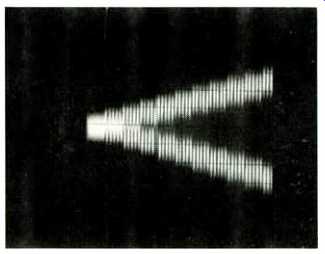

Fig. 10--Monotonicity test shows an almost perfect, symmetrical "staircase" display.

At the analog outputs, A-weighted S/N ratio measured 117.3 dB for the left channel and 118.2 dB for the right when playing the "silent" band of my CD-1 test disc. I can't recall any CD player that was as well shielded against hum or other forms of induced analog noise as this unit. Figure 3 is a spectrum analysis plot of residual noise as a function of frequency. During this test, of course, no weighting of any kind is used. Nevertheless, even at the critical power-supply frequency of 60 Hz and at its harmonics, the noise level was more than 120 dB below the reference output level of around 2.0 V. Figure 4 shows how THD + N varied as a function of output level, with respect to maximum (0-dB) recorded level. Here, THD + N is expressed in dB below maximum output level rather than as a percentage. Notice that there is practically no rise in THD + N at the 0-dB level, where analog stages of many other CD players often add their own distortion to the THD figure obtained. Even at maximum output level, THD + N remained around-97 dB, which corresponds to a percentage of 0.0014%. These results were confirmed almost exactly when, a bit later, I measured THD + N versus frequency at maximum recorded level. As Fig. 5 shows, I obtained a reading at 1 kHz of about 0.0015%. Again, I can't remember any CD player that yielded lower distortion figures, though a couple have come close. Further, whereas most players tend to show higher levels of distortion at high frequencies because of out-of band, non-harmonically related "beats," the THD + N of this Denon CD player never exceeded 0.0055% at any frequency. Although I passed a 20-kHz test signal--recorded on the test CD at 0-dB level--through my spectrum analyzer, the dynamic range of the analyzer precluded my seeing spurious "beats" at any frequency from 0 Hz to 50 kHz, so I saw no point in including a 'scope photo of the results here.

The CD-1 test disc has a track consisting of 60-Hz and 7-kHz signals in the 4:1 ratio used for measuring SMPTE-IM distortion. I don't usually test this parameter because I have found that a unit's SMPTE IM is usually of the same order of magnitude as its THD. In this instance, however, because THD + N was so very low, I decided to take a spot measurement of SMPTE IM. It turned out to be 0.0045% on the left channel and 0.0040% on the right.

Right-to-left channel separation at 1 kHz was 117 dB, while left-to-right channel separation at the same frequency was 113.5 dB. Separation at this and other frequencies is shown in Fig. 6. Even at 16 kHz, separation remained noticeably greater than 90 dB. You can take issue with Denon's approach to D/A conversion if you wish. Other manufacturers may, in fact, be able to achieve equally superb linearity in their various approaches to "perfect" D/A conversion. This much, however, must be said about Denon's Delta technology: It sure produces linear output at every level! Consider Fig. 7, which shows deviation from perfect linearity for both channels, using undithered signals from 0 to-90 dB. There was virtually no deviation for the left channel (solid curve), even at 90 dB, and about 1.8 dB of deviation for the right (dashed curve). These are truly excellent results. Further confirmation of the superb linearity exhibited by the DCD-3520 was obtained when I ran my low-level linearity tests, using dithered signals from -70 to -100 dB (Fig. 8). Under these conditions, even at 100 dB below maximum output level, linearity was off by only 2 dB for the left channel (solid curve) and a bit over 2 dB for the right (dashed curve). Dynamic range is defined differently by the EIAJ than by the new EIA interim CD Measurement Standard. Using the EIAJ Standard, I obtained a dynamic range figure of 98.2 dB for either channel. Using the EIA method, which involves running the fade-to-noise test available on the CD-1 test disc (Fig. 9), I calculated a dynamic range of just over 105 dB. The dynamic range is determined as the point at which the signal is overwhelmed by noise that is at least 3 dB greater in amplitude than the test signal itself.

Having obtained such outstanding linearity results and such high dynamic range and S/N ratios, it came as no surprise that the monotonicity test track on the CD-1 disc produced the new-perfect and symmetrical "staircase" display shown in Fig. 10. Notice how the magnitude of all steps--in the positive--as well as the negative-going direction--is identical, and how there is never a reversal in the direction of any adjacent steps. The frequency of the internal master "clock" of the player was accurate to 0.0364%. Once I completed these bench tests, I turned my attention to this remarkable player's tracking and error-correction capabilities. For this purpose, I used the test tracks on one of two special discs entitled Digital Test, produced by Disques Pierre Verany and distributed in this country by Harmonia Mundi. For tracks having linear dropouts, the DCD3520 successfully handled dropout lengths up to 1.25 mm without any audible artifacts. When playing tracks only 1.5 micrometers apart (the minimum pitch allowed in the CD Standard), dropouts up to 1 mm in length were successfully ignored. Finally, I played test tracks in which two successive dropouts were deliberately encoded. In this case, track pitch was increased to its nominal value. Again, the DCD3520 was able to handle two successive dropouts of up to 1 mm in length. The CD Standard calls for a player to be able to read dropouts of up to 0.2 mm in length under these conditions, so you might say that this Denon unit did five times as well as the Standard calls for.

The Denon's rugged construction also protected its laser pickup against any mistracking caused by external vibration. I really had to give the player a solid whack on its side before I could induce any sort of muting or mistracking. The intensity of that whack was beyond anything a right-minded owner would ever apply to his player!

Use and Listening Tests

I deliberately sought CDs which included solo instruments or at least moments of very quiet musical passages, hoping that during very low-level passages, I would be able to hear improvements when comparing the sound quality of this Denon player versus my reference unit. A recently released Delos disc (Love Songs, D/CD-3029), featuring soprano Arleen Auger accompanied on a Baldwin piano, suited my purposes very nicely. I must confess that I could not detect any difference in sound quality between the Denon DCD-3520 and my reference player. However, when I substituted a low-cost portable player and a mid-priced unit that happened to be in my lab, the differences were immediately apparent. The DCD-3520-and, for that matter, my reference player-produced silky-smooth vocals that were closer to reality (I have heard Auger singing "live") than the sounds produced by the low-cost competition. The tests were repeated with fuller, orchestral recordings, and once I knew what to listen for, I was even able to detect cleaner sounds from the Denon when using material that I thought would mask any such subtle differences. Clearly, the differences weren't all that subtle after all.

Denon has brought to bear all its digital know-how in the creation of this, their flagship CD player. More expensive units are available today, but you'd have a hard time finding one that performs better than this.

-Leonard Feldman

(Adapted from Audio magazine, Jun. 1989)

Also see:

Denon DCD-1500 Compact Disc Player (Jun. 1986)

Mod Squad Prism Compact Disc Player (Auricle, Aug. 1988)

Mission PCM-7000 Compact Disc Player (Aug. 1987)

= = = =