THE RECORD OR THE EGG

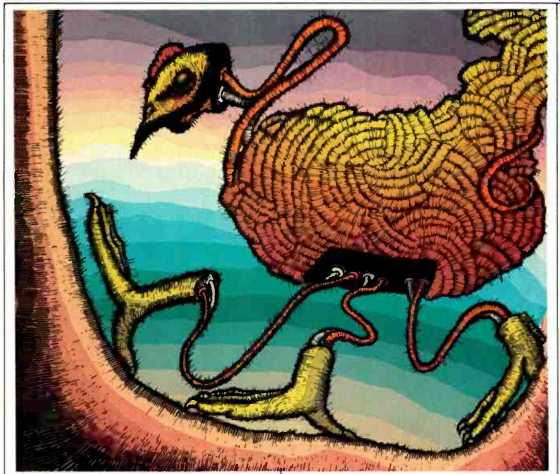

I have always thought that the chicken was nature's finest edible creation. I feel much the same about audible audio, so why not put the two together?

True, I eat chicken in parts, the way we get them today, but do I love to see and eat a whole chicken, well roasted! Upside down, two plump legs (no more) pointing skyward, and a hole for a head. Not surprisingly, I go for the whole of audio, too, which is always greater than its parts.

The whole living chicken is a fond memory, pre-Perdue, from the times when every farmhouse had them on the loose, ready to cross the road--straight in front of each passing car.

Wings flailing, legs pumping madly, feathers flying in squawking hysteria.

Brainless creatures! Why does a chicken cross the road? To get to the other side, of course. But never sedately. A chicken's sheer audio is formidable, along with all that visual ruckus.

But an unflustered hen is a friendly soul, stepping elegantly, each claw lifted adagio, eyeing you with a questioning jerk of the head while emitting inane little conversational noises to nobody in particular. I like the whole living chicken.

As a journalist, a commentator, I see both chickens and audio with an outsider's fascination. I'm neither a Frank Perdue nor a Bob Carver, nor even a Cole Porter, so it's just as well this column is set off by itself, under those useful initials ETC; because, you understand, I can't keep my professions apart. I like to look at the whole, and the whole of audio extends far beyond electronics--all the way from music theory to Ohm's Law, from Mozart to McIntosh, from Philharmonics to filters D and A. As I see it, all this is on a basis of total equality, from one side of audio to the other. The business of audio has always been music, but now we go ever further, into the newly related video arts.

And so many kinds of music! If it's recorded, synthesized, or reproduced, it's audio. Of course, an audio specialist may concentrate on some minute and highly technical bit of R & D--this is the glory of our advancement. One does this, hopefully, as one pulls off a leg from the roast chicken for detailed analysis in the stomach. A chicken is still a chicken. But the more fragmented our work, the more likely we are to forget the whole bird and amplify the leg. At all costs, we must avoid he supermarket approach-the shiny package of five legs, three left wings, and a disembodied neck. In audio, that simply won't sell.

Nor will the monkish approach: Burying yourself in a small electronics corner and forgetting the pesky outside world. If monks and scholars can fall into that, don't think we can't. Even with a technical paper at the AES, you still haven't got an audio whole, just a part.

I bought a gadget the other day, a plastic pencil holder the size of my hand, with "ETC" on the outside. Its feature was a magnetic plate that grabs a flat piece of metal which you stick on a wall or window. A total dud.

Too many technologies, and two were defective. First, the magnet came unstuck after a day. Then the piece of metal on the wall fell off with a crash.

Wrong adhesive. I threw it out in disgust.

The monks and scholars live serenely in their isolation, but not the engineering technicians. The consequences of being a too-isolated link in a chain are horrific-shortfalls in perspective! Sometimes, we seem to lose our very hold on reality. The military? Very purposeful people, but they build troop transports that won't transport, missiles that miss, bombers that bomb out. Myopia? Money doesn't seem to help. There are plenty of misguided civilian disasters of the same sort--shortsighted, bogged in detail, minus the larger know-how which might make them effective. Our own area, that audio whole I speak of, is hideously prone to similar catastrophes.

It is a wonder that so much of our assorted products-in all walks of artistic and industrial life, as well as our own-still remains viable, useful, workable, even excellent. A lot of people do have good vision, speaking metaphorically. They can see the whole, and shape it out of the parts. Not only all the hardware, the equipment, but even more remarkably, the sonic "soft-gear," as I tried to name it a while back.

(Software is for computers and should stay there.) No, Beethoven really should not be called soft-gear, but he is obviously a part of the whole audio, through no intention of his own. Music, and all that goes with it, is our soft-gear, or 99% of it. Cut out the music in audio, and what do you have? A super-fi, high-end recording of your vacuum cleaner. It is the musical product that really shapes just about everything we do in a practical way. Our farseeing people need to know all about music, every kind, as well as the audio technologies. Not only music but musicians, the acoustic performers and the synthesizer types at the far ends of their joint spectrum. Why else did the systematic Germans invent the Tonmeister, equally versed in music and engineering? And why do we increasingly explore the same? The whole audio is actually a three-legged chicken. There is music (the soft-gear). There is audio technology (the equipment). And there are people (the consumers). The market, as we call it, and all those forces that make markets go. In the larger sense, this is economics. And that's our chicken's third leg, a fat one. Absolutely undetachable from music and audio engineering.

People, markets, economics shape us as relentlessly as evolution shaped the elephant and the giraffe. People are diverse-so must be audio. People demand many products, mass and not-so-mass-we must supply them, each in their practical way. We have "created" a demand for enormous loud sounds inside automobiles-we have the know-how-and the same for the ubiquitous portable cassette player, alias the Walkman (the most familiar of its trade names). But isn't there also the CD? And just look what is now available, at considerable cost, on thousands and thousands of CD releases! May I humbly suggest that the percentage of the total market isn't the point; it is the "whole," the complete entity of each separate market, large or small, that matters. Is the CD viable? You bet. And it remains obstinately classical in the large, because that is where this "whole" works best.

I am even less of a pro economist than a trained electronics engineer, but in our larger perspective, how can anyone avoid economics? So I often swerve, at my own risk, across our borders into various sorts of economy.

Every single recorded or reproduced note of a work by Beethoven is a note in our present economy. If we have that composer with us, it is because many minds have been at work to integrate his sound, so unlikely in its original form around 1800, into our present audio production and listening.

I was amused, recently, to receive a letter from a reader in New Jersey concerning my ostensibly economic Canby Principle No. 2 (revised, as per the April issue), the "Two-Plus" theory. I spoke of monopoly, anathema in this country, and then went on to make up words-biopoly and polopoly-which just sprang to mind. Attila Balaton of Summit, N.J., who has studied formal economics (and might even be an Economist) wrote to point out that n the late 1800s, the Classical School of economists had already "derived all the concepts needed to define the condition of different markets and their impact on price fixing mechanisms." These Classic pros, Attila wrote, set up a number of economics terms to cover the situation, the most famous of which, of course, was monopoly.

Guess what came next? Duopoly and oligopoly! So it seems that I have reinvented the wheel. That's okay by me, and in fact I am happy to have re stumbled on such a long-lasting idea from my own outside perspective.

Long live the Classical School! When things go wrong with the whole in our technical age, there is real disaster, failures of product on a monumental scale. Maybe it is a kind of hidden benefit that our largest corporations can usually take the enormous losses involved and still survive. Smaller companies, in contrast, just crumple up. Or fold. The American system has it this way, whatever you may feel. It is good that we can afford huge risks for enormous projects that may or may not succeed. It is also cruelty for almost everyone involved-except, perhaps, the accountants.

Moreover, there is another somewhat striking feature of virtually all such failed enterprises: They don't blow up with a bang; they just vanish. One day they are there, the next day nobody has ever heard of them--nobody, at least, in the companies' public relations departments. The projects no longer exist. Key people just aren't around anymore. They aren't fired--not so you'd know it. They just go poof.

All of which, in subsequent times, makes for an astonishing situation. Out of sight, out of mind. In a few years, nobody inside the company has ever heard of the project! Only those, high or low, who were directly involved and can never forget. It's a waste of energy, I think, to "blame" a large company for this sort of bland cover-up.

Because these projects are so big, the "wholeness" of the thinking is enormously hard to achieve. Hundreds of workers, mountains of equipment, vast sums of risk money-and who is the genius that can hold it all together? There is obstinacy and inflexibility on high, and there is that old bugbear, hierarchy, so the bright minds below are afraid to tell the boss. I'm merely describing what is familiar to us in the audio world. I do believe (speaking a sort of economics) that today the very soul of our business, our field, is in small enterprise. And yet what does every successful small enterprise do? Get bigger.

I think the appropriate word for success in this concept of a whole-the audio whole, in particular-is fluency.

Fluency means easy communication between all the developing segments, yes. But more than that, it is the ability to flow, to adapt, to move easily across professional lines, to fill gaps where they need filling, no matter what (like that adhesive, the wrong adhesive). Also, it means to flow inward, adapting and evolving the whole, down to the tiniest detail of engineering. Small companies keep up the flow; big companies freeze. And do not forget the soft-gear, the ultimate, crucial end product of all our ventures in audio--now in audio/video. The big corporate failures are like big chickens with deficient parts, a good leg and a bad one, fine white meat and a diseased liver.

Not viable! Doomed to die. Inedible.

I have deliberately stuck to great generalities here, but my mind is on specifics. Paradoxically, because the more notorious failed products are really no longer the concern of the present parent companies, whose people hardly know about them, I think an outside view of a few might offend nobody. The past is past.

One of these days, someone will design the ultimate chicken, with the best of intentions, of course. Two swivel heads, for better fuel intake, but without wings or legs. It won't go anywhere, though. Not even across the road.

(by: EDWARD TATNALL CANBY; adapted from Audio magazine, Jul. 1989)

= = = =