by DAVID LANDER

In the 1950s, the press spun stories about Emory Cook which, three decades later, read like myth. Consider the following chapter in this hi-fi pioneer's media odyssey.

One morning, the founder and proprietor of Cook Laboratories got a call from a local real-estate agent. A client who'd just moved into a house near Cook's in the placid New York City suburb of Pound Ridge had phoned, threatening legal action. For much of the previous night, the new homeowner complained, the sounds of trains had hammered through the ambient darkness. Yet during their real-estate dealings, the agent had never so much as mentioned the nearby railroad line.

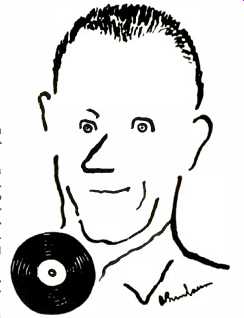

The only trains in Pound Ridge were those on Cook's recording, Rail Dynamics, one of the earliest titles in his highly popular "Sounds of Our Times" series. In about 1950, the fledgling record producer was the first to imprint the realism of railroading on disc, an achievement that won him the enduring affection of a growing audiophile community.

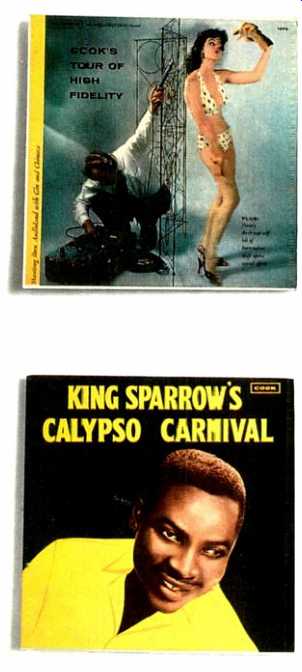

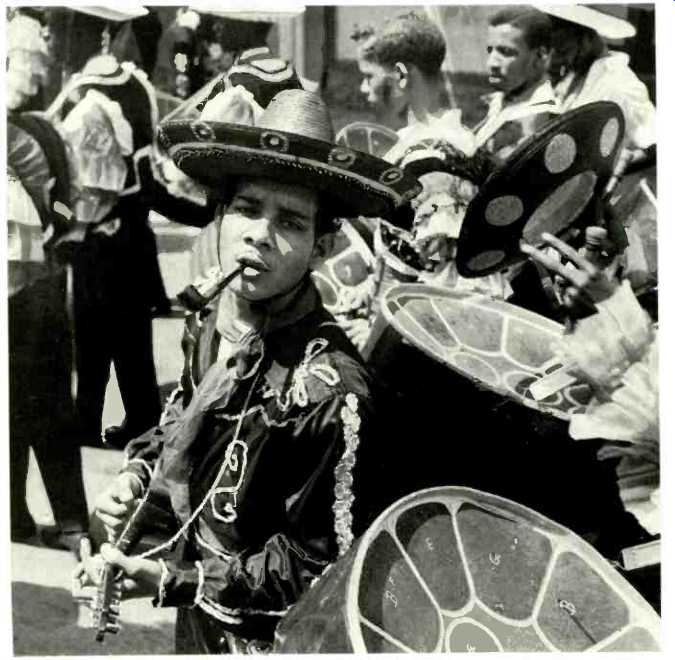

Those who took Cook's tour of sonic oddities could visit a chicken farm, a burlesque show, a naval cruiser, or au Air Force base. Hurricane-strength winds howled on his recordings, firecrackers exploded and babies bawled. There were musical dynamics, too, of course--including a New Orleans bugler, West Indian steel drummers, and organs played in a Mexican church, New York's Paramount Theater, and Boston's Symphony Hall.

All this captured the collective imagination of the press, and parables about Cook abounded. It was written that valuable equipment had been lost to the tides when Cook recorded Voice of the Sea, an album of nautical sounds that took years to assemble. And that, while 'Hiking thunderstorms atop New Hampshire's Mount Washington, he had come perilously close to being struck by lightning.

"Through ... devotion to sound quality, he has become a kind of senior oracle of high fidelity," one writer reverently noted in Musical America. Another, in The New Yorker, devoted two installments to a profile of this "brash, quixotic" man with his "almost mystical reverence for sound." Cook clearly has earned the respect these and other media ac counts afford him. But while the anecdotes they contain are beguiling indeed, he now denies the veracity of many, including the one about the invisible Pound Ridge Railroad.

Although Cook does concede that he may have come close to a prophet's fiery demise while recording on Mount Washington.

Viewed in the context of its time, this audio apocrypha is easily understood. After all, the '50s were heady days for an industry just entering adulthood. Its founders competed in an olympiad of sorts, and the most exuberant player in the tournament of decibels may well have been Cook himself.

Emory Giddings Cook was born in Albany, N.Y. on January 27, 1913. "Father happened to be Steinmetz's attorney (if of interest)," his curriculum vitae states with characteristic dry succinctness.

In 1932, after four years at Phillips Exeter Academy and one at M.I.T., Cook enlisted in the Army Air Corps. He was discharged two years later and matriculated at Cornell, where in 1938 he earned an E.E. degree. .Jobs with New York Power and Light and with the engineering and construction departments of CBS followed. Then, from 1942 to 1945, Cook worked with the Navy as a civilian member of Western Electric's Field Engineering Force. For this, the Navy awarded him a commendation for developing a device to train fire-control radar operators.

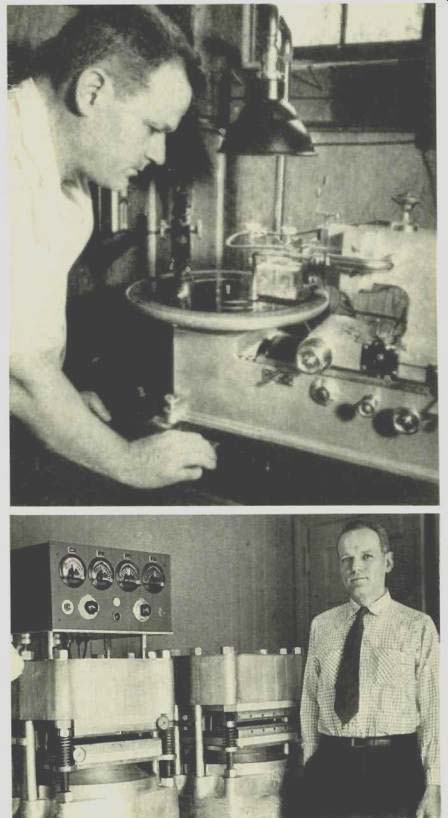

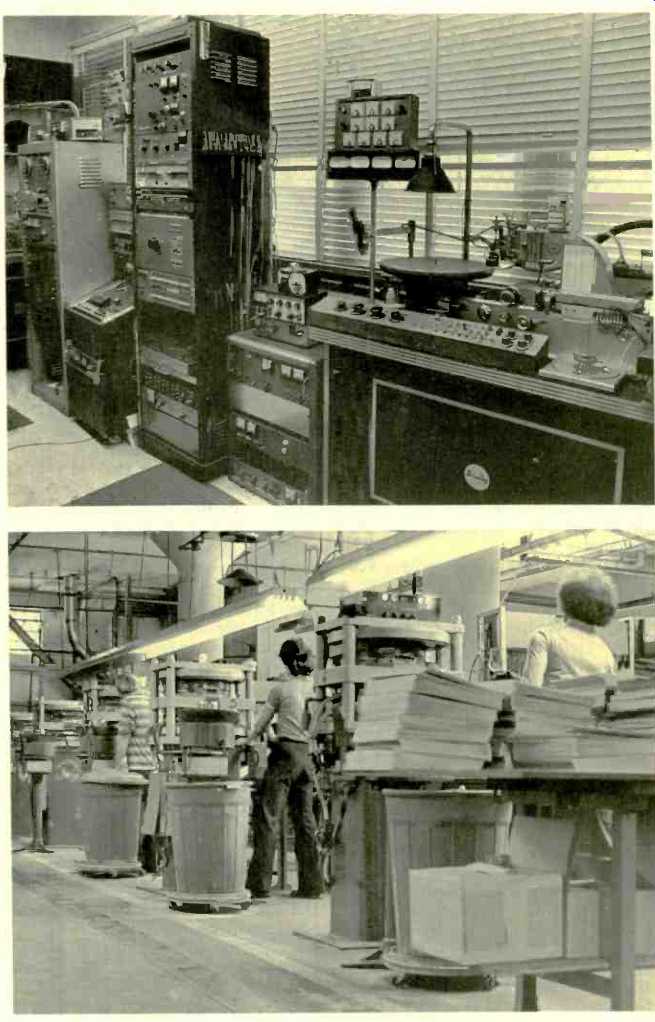

At the close of 1945, Cook left Western Electric and started Cook Laboratories in his basement. A few months later, he was offering record companies a feedback cutter of his own design. In 1949, with the production of live radio shows on the wane. WMGM decided to convert several broadcast studios for recording. Cook, who had been producing masters for the station's sister company. MGM Records, was signed on to design and install recording equipment. This led to a consulting contract which lasted several years and helped subsidize Cook's other activities, one of which was the manufacture of test records. When Cook hung up a sign at his 1949 Audio Fair exhibit, stating that one of these records contained a 20,000-cycle tone, his display became a focal point attendees.

The annual Audio Fairs, held at Manhattan's hotel New Yorker, were a gathering place for the electronics trade as well as audio hobbyists and others curious about the new phenomenon called hi-fi. At these events, Cook often teamed up with speaker maker Rudy Bozak.

His records--which included stereo program material as early as 1952--and Bozak's loudspeakers proved an irresistible combination. Converts to the hi-fl cult multiplied along with the two men's sales figures.

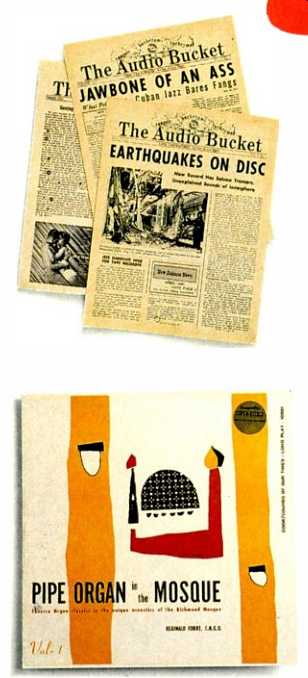

At least part of Cook's success can be attributed to the showmanship he displayed at these expositions: One year, he included a parrot ill his exhibit, with a sign reading "Sales Manager" on its cage. His disdain for high seriousness was also evident in the whimsical copy he wrote for his record jackets and The Audio Bucket, a newsletter that seems ironically named, given the amount of arid humor it contained.

The nature and pervasiveness of this humor make it easy to believe that Cook, who once covered the center hole of his LPs to assure purchasers of their virginity, enjoyed inventing romances for innocent interviewers. It's also possible that some journalists missed the tongue-in-cheek tone of items in The Audio Bucket and rewrote them, deadpan, in their own publications.

Whatever the case, since Emory Cook denies so much of what his 1950s press clippings proclaim and sniffs at the persona they created, surely it's time to set the record straight. Here, then, are three warranted-to-be-true stories. Their dimensions are human rather than mythic, and they help reveal the measure of one of hi-fi's pioneers.

In the late '70s, Cook attended a recital by soprano Phyllis Curtin. He'd recorded her more than two decades earlier and hadn't seen her once in the intervening years. As he stood outside the auditorium, Cur tin passed by, recognized him, and threw her arms around his neck.

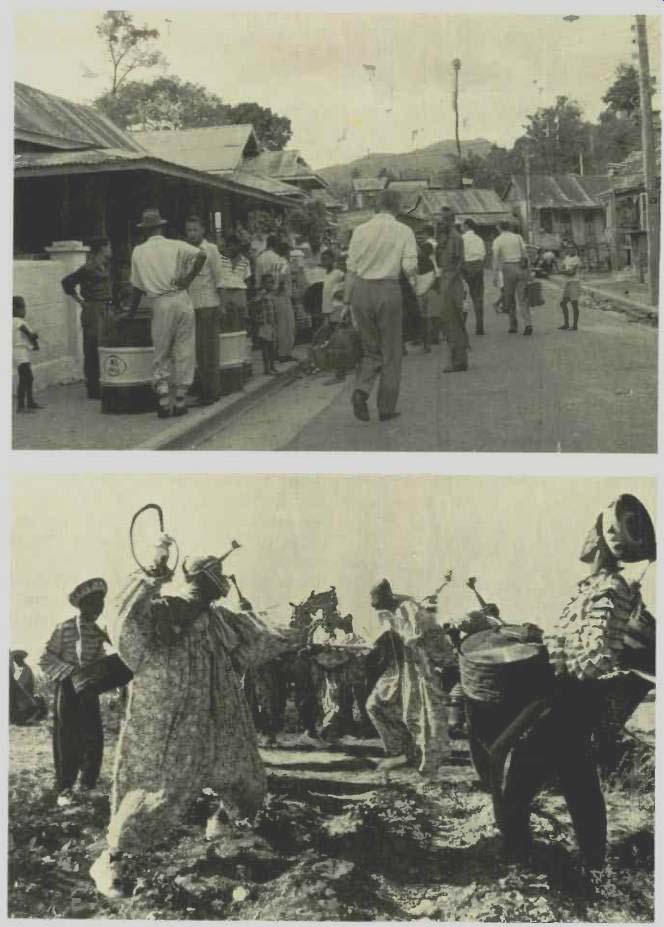

Not long ago, Cook's lovely wife, Martha, got a call from a prospective record purchaser. Ile told her that he was a boy when her husband had come to his native Trinidad to re cord. Ile still remembered that, when Mr. Cook appeared each morning for his taping sessions (done, of course, outdoors), he invariably had pockets full of candy, which he would distribute to the children.

Lizzie Miles, a black singer from New Orleans who Cook discovered and recorded late in her career, sent him a number of letters. One of these contained a "hello to you staff" and the benediction, "God bless all of them." Miles concluded with a reminder to her producer, "Always remember," she wrote, "you made one old-fashion, creole, antique gal very, very happy."

-D.L

-----------

You were one of those hard-core hobbyists who, before the development of tape, was using a recording turntable to cut your own lacquers.

Just off the air. NBC. Toscanini. I think that was probably '44, '45--some where in there.

Wasn't it the poor quality of commercial recordings of the time that got you into the business of making records?

Most of the records made by U.S. companies were miserable compared with the European product. I admired the British in a general way because they made good records. They operated with greater care. In this country, we were making junk, crank-it-out junk that was just bad in many respects acoustics, microphone placement, and particularly the mechanics of the pressings. The pressings were deplorable-off center, un-flat, distorted, all that. Somehow, that did two things, think it gnawed away at whatever feelings of patriotism might have existed in a young man. It also opened up an opportunity. Here was something that could be done that was at least worth while. I wouldn't have been in the record business except for that--bad product.

Was all American product really that bad?

Sometimes it wasn't bad, but it was never predictable. RCA sometimes mace good records, but you never knew what they would be. They were unable to control quality.

When you started your company after World War II, though, the point wasn't to make records. You started out making cutters, didn't you?

Feedback cutters. All cutters that are used today would be feedback cutters, but then there was only one, the Western Electric. On a feedback cutter, the driving coil has a sensing coil on it which is used to supply the feedback signal in order to discipline stylus motion. It's like a servo. Olson tried to make a loudspeaker like that, and did, but it didn't come off very well. Probably too fragile. I emerged from the war with a Western Electric license and, using their patents, built a feedback cutter for sale instead of for license.

The record companies then paid a royalty to Western Electric for each operation, each record that was made on Western Electric's cutter!

What, specifically, were the problems you were trying to overcome with your cutter?

Distortion and frequency response. The available in those days weren't very good. The 78-rpm records would establish that.

How did you get from cutters to making records?

In 1949, we exhibited test records at the Audio Fair run by Harry Reizes. We also had music records made in the studio simultaneously with MGM con cert records. And people weren't interested in the cutter, they wanted the records. We went ahead and started making records then and there.

I understand you put up a sign up at that show saying you had a 20,000-cycle tone on a test record. Did any one else have such a thing prior to that time?

Well, I hardly think so. If they did, they kept it to themselves.

I wonder how many people were actually capable of hearing it.

The curiosity is always there. Whether anybody could hear anything or not is another question. The famous question: "What! You mean you can't hear 20,000 cycles? What's the matter with you?"

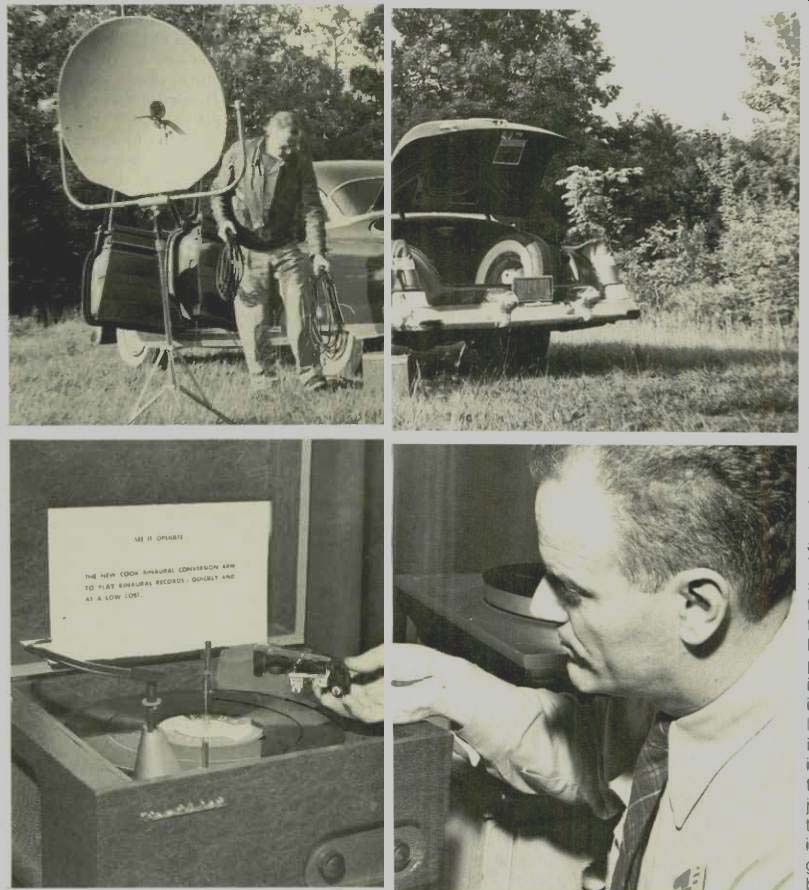

You first showed your binaural recordings at the Audio Fair in 1952. Were these made with dummy heads and meant for headphone listening?

No. Absolutely not. They were made with microphones spaced 6 feet or more apart. I used the term binaural and shifted to stereo after the West Coast decided that was the language.

The reason the West Coast did it is because they wanted to be different. If I called it stereo, they would have called it binaural, for all I know. They didn't like it that I started up first naturally. I like [the term] stereo better anyway.

I understand these recordings created quite a stir at that show. Tell us about them, and about the hardware used to play them.

Well, there were two bands of grooves-one for the left channel, one for the right-two cartridges, and a bifurcated arm. [A company called] Livingston made an arm. Livingston is a town in New Jersey; Ched Smiley was the guy. And Scully made an attachment that you could put on any arm. You had the left channel on the out side, the right channel on the inside. You started them both at the same place, and it had half the elapsed time of a regular record of this time. So you connected one side to one amplifier and one loudspeaker, and the other to a second amplifier and a second loud speaker.

How well did this system work?

I don't think you'd give them away as Christmas presents to your wife or girl friend. It wasn't just duck soup, but it wasn't all that bad either.

It must have imposed serious time limitations. How much music could you get onto a disc? Enough to make it commercially viable?

Twelve minutes, roughly, would be about maximum. I never expected it to be commercial. It served as a lubricant, to get something started. But we certainly sold a lot of records. Probably 500, something like that, of each one. We had, four, five, six records.

Acoustical space is now an important factor in recording. Did people in the record business think much about that in the early '50s?

I certainly did. All you had to do was go around New York and see a half-dozen studios. Commonly, I would say, the biggest one you'd find would be about the size of this room--28 x 35 feet or so, with a high ceiling. This is some thing you don't do with a concert orchestra. If it's a jazz band-well, may be-but there's going to be no acoustics. Reverb chambers were some times used. Other than that, you had this horrible business of doing it dry in a place this size when it should be three or four times this size. I don't know if you remember Toscanini and Studio 8H. That was one extreme. That had no acoustics, and it sounded that way. Pretty unpalatable.

What was your concept of the ideal situation?

You have to imagine something that's similar, in acoustical behavior, to a typical living room. There is no such thing but, keeping that in mind, you have to recognize that this is the sort of place a recording's going to be played in 99% of the time and behave accordingly. Normally, living rooms are terribly small, so you can't expect the feeling of having been in a concert hall if it's a concert hall, or a theater if it's a theater, or a nightclub if it's a nightclub just by putting the microphone down the throat of a horn and then reproducing it in somebody's living room. It isn't going to sound right. You don't have to be too smart to know that's not the way to do it.

How did you do it?

Well, I used the old live-end/dead-end studio idea. What you do is plug one ear. You have to get accustomed to the business of sticking your finger in one ear or the other, whichever, and becoming a microphone. Two ears are not a microphone.

Certainly not a monaural microphone.

A so-called stereo microphone is not two ears either. They [the stereo channels] are too close together, for one thing-besides which, they don't handle incoming information in the same way at all. So you have to find a place [for one microphone]-and oftentimes, it's very sensitive, within an inch or so-and then do the same for the other microphone. You have to plug one ear and listen.

How did you arrive at that technique?

I think I learned it from a guy who used to work in the ERPI Studios in the Bronx. Gordon Jones. But you can't just pick up and do it, see. You have to establish a norm in this condition, and you have to listen long enough in your life-through the weeks, through the months-for it to become the norm.

The best man I knew for that was Joe Kuhn out of Chicago, who I brought in to help with the MGM installation at 711 Fifth Avenue. He was totally deaf in one ear. I don't know whether it was the cortex or the ear or what, but he couldn't hear a thing out of one ear.

This is an interesting thing, because he was an ideal microphone. Of course, you have to be insensitive to being laughed at--the young-timers would laugh--but that never bothered me much.

Did you have a favorite microphone placement configuration?

No, no. It depended on the scenario. It just takes knowing what you're hearing. That's all.

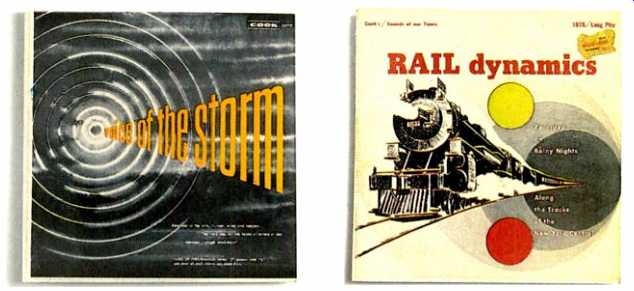

And the scenario for you invariably involved recording in the field.

I never operated in studios. I'd always do it in the field. Let me tell you some thing that's pretty serious. If you've got to bring a symphony orchestra into a studio, then they don't feel comfort able. They can't hear each other: that's not a normal environment. You get a different type of performance--unless you've got hard-bitten professionals--than in the field, in their own natural environment, it you put a steel band inside four walls, you can't record it. You've got to record it outdoors.

What microphones did you use?

I designed my own. Capps made it. It wasn't particularly innovative. What was good about it was that I had a damped cavity in the backplate which nicely cancelled the refraction pattern.

Oftentimes, an omnidirectional micro phone-depending on the size (this was about an inch in diameter)--will give you a little bulge at 8 kHz. This ore went out, bureau-of-standards flat, to 15 kHz, and with that damped cavity, it was set up to cancel the refraction bulge.

You said your mikes were always at least six feet apart.

Never less than six feet. If the room is too small for that, you don't use it. If you have a room that small, then it's not stereo anyhow.

Do you feel there should be a maximum space between mikes?

I don't think you can say that. In the Paramount Theater organ job, the microphones were 80, 100 feet apart probably. When recording an organ, you have to get close to the shutters or you don't get it. It would sound like a mammoth cave.

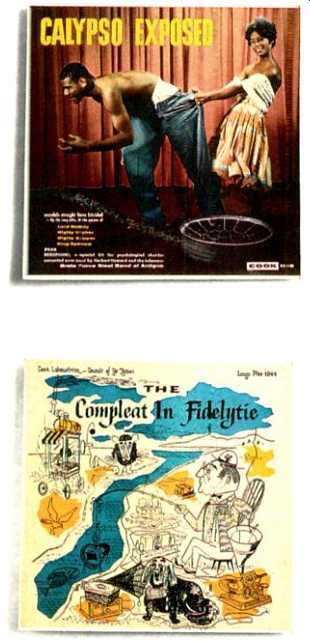

You developed a method of manufacturing records called Microfusion. In stead of stamping vinyl discs, you molded them by fusing powder particles. How did this come about?

K. R. Smith [a former executive at Muzak who had started his own plating firm] and some professor had developed the idea of a sintered vinyl biscuit, sort of like a sponge. He had a machine in his basement which cranked out 7-inch biscuits more or less automatically. One day, he took me down there after dinner and showed it to me, and I was completely taken aback. I'd never seen anything like it before; it was a great big surprise. So we started out to make one big enough for 12-inch. This would have been about 1954.

You found that this process resulted in less surface noise?

There were a lot of good things about it, but at one point, they [Smith's company] were taken over somehow by a bird dog for Dutch Philips who sought out opportunities for them all over. By that time, we were trying to run a sintering machine producing 12-inch biscuits. And suddenly one day, this guy called and said, "You're going to stop.

We're going to come over and take the machine out."

Did they actually have a patent on the process?

Oh, yeah. They'd filed. I had a license, but they said, "Sorry--no longer licensed." So we decided we'd do it without sintering. It took us two years, but we got into doing it with the powder without sintering. It's a little difficult to describe. It's a whole series of procedures that allowed it to be done from the straight powder, which of course is even better than sintering because heat history is the enemy of all plastic.

Heat history is the product of tempera ture and the time during which the plastic has been subjected to that temperature. Something that has not gone through an oven, that's been changed from a powder to a tangible biscuit that can be picked up, is bound to be better.

And you used this process right up until the time you sold your company last year. Obviously, you still feel it's superior to hot extrusion.

Not just that, but you don't have to make several thousand records at a time to do it economically. You can make a couple hundred, a hundred, whatever you like.

Back in the late '40s, you developed a recording process that you called QC. What, specifically, was that?

It was a means of tailoring the signal, before it got to the cutter, in such fashion that you could cram a much higher level on a record without abusing the playback function. It's easy enough to make a record that's impossible to play properly just by pouring it in. Making it playable is what that was directed at.

Did you compress the signal?

Well, it depends on what you call compression. We would dip the bottom end very momentarily; it would come right back again. It doesn't get noticed.

What else gave your records the edge over so many others?

A great deal of attention to detail in mastering and plating.

You always did your own pressing?

After 1954, we certainly did.

You had a pressing plant in Trinidad for a number of years. When was that? And why did you start it?

It probably started in '56, '57-some where in there. We exported from there to Barbados, Jamaica, Antigua, and England. We had been exporting fantastic quantities of records to Trinidad.

A lot of the people that bought them didn't have phonographs. They had nothing to play them on, but they'd put them up on the wall or someplace, against the time they would. Music is more important to many people over seas than it is to us. To us, you know, it's a pastime and a plaything and very agreeable, but it isn't food and drink.

To some other people it is.

You've linked the growth of television with the recording industry's growth. Didn't you predict, back in the earliest years of television, that the medium would create a backlash and send a lot of people running to their music systems?

The escape was always away from the television set. One way to get away from this thing is to harness yourself to a radio or records. The common problem with radio is that you never can find a station that plays what you want to hear at the moment. Record sales statistically, could be offset against TV sets. They did this. The industry did careful research of this sort. Let's take nice capsules-the population of Peoria, Ill., for example. When they in stalled [television in] Peoria, it was done in an orderly way and all at once as much as possible. This is the way it happened in the '40s. TV sets were sold to X percent of the available homes inside of six months. And it turned out that, six months later, you got this increase in record sales. It is inescapable that record sales went well up time after time after time. Very, very interesting. It's never been published.

You did some medical experimentation with white sound which, as I under stand it, is actually a derivative of white noise.

Well, we call it white sound because noise is a term which has negative connotations.

You used it as a pain killer?

It's probably more like a distraction. It doesn't kill anything. It diverts. My guess is that it jams up the cortex with meaningless information. It's like a jammed-up switchboard. All the telephones are ringing, and there's nothing you can do.

And you've documented this on film?

Oh, yes. I have film of an elevation and extraction [of a tooth] on, I think she was an 8-year-old girl wearing ear phones. And we had a chalazion [a cyst in the eyelid] operation done by an ophthalmologist who was a friend of mine. They're both in the same film. We showed these two things down at Bethesda, Maryland, the Naval Hospital--the dental thing for the dentists then the chalazion [for ophthalmologists]. They're both about 10- 20 minutes long. And when the chalazion thing came on, all the dentists got up and left. They couldn't stand the sight of blood coming from the eye [laughs]. And vice versa for the ophthalmologists. You know this is true. It happened all morning long.

So the technique is effective.

Oh, sure. But it takes some control and discipline on the part of the patient, which isn't bad. You've got something to do instead of nothing. It doesn't do much good for an appendectomy; I don't think it would work for that. The obvious goal is the labor room. It's just beginning to come into the labor room. And this is now--how many?--nearly 30 years later.

Let's move on to your recordings. One of your first commercial records was a collection of music boxes. What led you to produce that?

Didn't cost anything. I mean, it cost very little to record. After all, it wasn't a union musician.

What made you think people would buy such a thing?

Well, it was coming on Christmas, and it seemed like a possibility. It's a Christmasy kind of sound. Besides, it also had "Jingle Bells" on it [laughs]. It was basically nostalgia.

Somebody once said your greatest innovation was the royalty-free record.

That was Frank Walker. He was head of MGM Records and, before that, manager of RCA Victor. He was absolutely right [laughs]. I have no objection to his having made the remark. It was a perfect remark.

The first record of yours that audiophiles are likely to remember is Rail Dynamics, the recording of trains. Didn't you work on that mainly at night to avoid extraneous sounds?

You can't do it any other way. They always have lights. You go to a railway station or a switching yard, and you'll find there's plenty of light around.

Just where did you go to record?

Mostly Peekskill; some of it was Harmon [both north of New York City]. Harmon was where they used to switch from electric to steam to go West.

And you wanted the steam?

Sure. Peekskill is a mountainous area. Very nice for acoustics, across the Hudson River and back. The sound bounced across.

Did you have to get permission from the New York Central to do this?

We got permission. I oftentimes had at least one person helping because it's a lot of luggage, a lot of weight to hassle on up the steps of a passenger car.

You said the original version of Rail Dynamics was recorded directly onto disc. Does that mean you did a later version on tape?

I added to it with tape later because then we went to stereo. The first one was released in mono on 10-inch. Then, when it was converted into 12-inch, we made it into stereo. Of course, that had to be done on tape.

And this was around 1950. What made you think people would buy a recording of trains?

Well, I really was very apprehensive about the idea. I then became quite surprised, and apparently some of the other folks [in the record business] did too. Because MGM pressed them all, it was very evident to them that a lot were being sold. That's where that royalty-free record remark came up. Frank was the boss at MGM.

But why trains?

Well, is there such a thing as nostalgia? And hadn't everybody ridden on a train-at that time? Now you find people all over who've never even been on a train.

Well, the toy train industry isn't what it was in the 1950s, but it's still chugging along, isn't it?

At one point, we went up here to American Flyer [formerly based in New Haven, Connecticut, not far from Cook's Fairfield County headquarters] and tried to get them to use this record in connection with selling their trains. The guy came out with a very potent re mark-finally-a logical reason. "The record is too good." He didn't mean that as a compliment. He meant it's too realistic. The train takes imagination, the record doesn't. Well, it probably could have been done by doubling the speed of the record [laughs].

Another one of your recordings was called Voice of the Sea. Didn't that take a long time to produce?

It was probably three or four years. I'm just guessing, but it was a long time.

And you did anenormous amount of travelling for it.

Not all at one time. I guess that started up in 1953, perhaps '54. Going up the coast of Maine till the roads tended to get narrower and narrower, and back through Massachusetts-heaven knows everyplace else. The Queen Mary horn came out of Manhattan, the Lower West Side. We rode on the cruiser Columbus at one time. They were on route from someplace to someplace. I already had Navy connections of some obvious merit.

And your idea was to capture the various sounds one would hear aboard such a ship?

Yeah. General quarters and all that.

In one of your newsletters, an item alludes to the equipment you lost while making Voice of the Sea.

That's somebody else's gag. No, that never happened. I might have lost a microphone somewhere, but I didn't make an issue out of it.

You released a record with some mysterious ionospheric sounds on it. Precisely what were they?

Nobody I know is around anymore who would be able to answer that question in scientific terms. It relates to shock impulses. A high-intensity lightning strike, let's say in the Southern Hemi sphere, will be propagated in the ionosphere to the Northern Hemisphere; very much like a wave guide. But it will describe a semicircle and be guided by the magnetic lines of force. Going back and forth, these will give off electromagnetic energy, some of which is at audio frequencies.

How were these sounds picked up?

With a very, very long wire for an antenna, away from civilization-no power lines, no homes, no other disturbances-because the level is very low.

These sounds were provided to you by a scientist who did the actual recording. Another scientist, someone named Hugo Benioff from the California Institute of Technology, provided you with earthquake sounds. How were these sounds recorded?

That's simply what came off the seismograph. But it was reproduced at quite a few times its actual speed.

I believe you pointed out that what the seismograph records is not really audible until it's speeded up. Did the result actually sound like an earthquake? No. Unless you're right on the fault, you won't hear snapping and crackling.

You once recorded a burlesque show. A New York Times review of that record reported you smuggled your equipment in. Was that actually the case?

No, of course not. [The burlesque show's producers] were delighted for the publicity.

Where did you set up all your recording equipment?

In the pit, with the orchestra. I put the mikes on stage on a foam-rubber pad.

That was the sneaky part of it, because it wasn't supposed to be commanding attention from the audience. The big thing is the gate, you know. You don't want to interfere with the gate under any circumstances.

How did the showgirls react to being recorded?

Well, these people are hard-bitten. You know, it's amusing. At least it was something different that night.

At one point you went from pressing your own records to manufacturing discs for other people. When did you get into that?

1958, 59.

And when did you record the last title for your own catalog?

Probably '59.

In terms of unit sales, at what point did something become a best seller?

For us? 50,000, I would say.

You did a number of recordings that featured New Orleans jazz performers. How did you find these artists?

Lizzie Miles, for example. Just walking along the street in New Orleans, in her case. She was a pro. She was 60 when I found her.

You've transcribed and kept segments of letters she sent you. You seem to have gotten to know her pretty well.

Probably as well as any white would have.

She says in one letter--it's dated February 12, 1955, Lincoln's Birthday, which is probably a coincidence-that "only an un-prejudice (sic) genius like you could realize that I could do better than what you heard me with that bunch of loud discords I was hollering with."

She was trying to be nice. Well, I was unprejudiced and still am, I think, it gets in your way, if you're prejudiced, depending on what you want to do.

It certainly would have kept you from a lot of what you did. All the black music from the Caribbean that you recorded--the Calypso, steel bands, and such. In fact, you had an entire Ethnic Series of recordings in your catalog.

Oh, yeah. Much of that is out of Trinidad. And Granada.

Are you an amateur anthropologist?

Sure, sure-very amateur [laughs].

Seriously, did an interest in anthropology prompt some of this?

Well, I met Herskovits [Melville J. Herskovits, a Northwestern University anthropologist] one time. He was commissioned by the Carnegie Corporation, back in the early '20s, to make a study of "the Negro in the Western Hemisphere"-that was the language used-and he went on with that for a long time. I remember running into him at one point. A lot of the folk material collectors did.

Some of the folk material you collected was never released. Can you give any examples of this?

I have some material from the Sierra Madres and other parts of Mexico and the Gulf Coast, I think.

What did you record in the Sierra Madres?

Indians. Tarahumara Indians. They sing and whistle and blow on pipes.

There's also drumming. They're probably almost extinct now. They're headed for extinction, if they're not. They're unable to reproduce. Nobody knows why.

Don't you think material of this kind should be made available somehow?

It will be made available. It's not going to burn down with the building. The Smithsonian has expressed some interest in it.

We started to talk about Lizzie Miles. What was the first album you did with her?

I think it was Clambake on Bourbon St., the one where she ran with the whole orchestra and shouted. She was a shouter. She had become a shouter.

She didn't need the microphone. That was all right: that's Lizzie. But there was something else there besides the business of being able to belt it out like a 50-watt amplifier.

She gives you credit for sensing that.

Well, sure. I sat her down in a chair and she sang to herself. I asked her if she ever sang to herself at home.

You called one of her albums Hot Songs My Mother Taught Me. Were these tunes really passed down that way?

I think all those songs were in piano sheet music. People don't realize how far back the sheet music business goes.

How far back did her songs go?

I'm just guessing, but some of them were 19th century, for sure.

You recorded a bugler in New Orleans, Sam DeKamel. Did he make a living playing the bugle?

Well, he did that and he sold waffles on the street. That was how it started. The bugle was how he attracted customers, made them know he was in the street, you know. If you don't happen to be looking out the window and say, "Oh, there's Sam," you wouldn't know.

He'd go by. You've got to do some thing. You've got to sing or wave rattles around or make some kind of sound.

And there was a singer named La Vergne Smith.

Yes, LaVergne Smith, whose boyfriend was a calliope player.

You pronounce it "cal-ee-ope." I al ways thought it was "cuh-lie-uh-pee."

Well. we call it "cuh-lie-uh-pee" up here, but they call it "cal-ee-ope."

Is he the performer on your record, Calliopes & Nickelodeons?

No, that's not a calliope. That's a diminutive version of a calliope. It's a contraption that was made up for Milton Kaye, who used to play it on the Henry Morgan show on WOR. It sounds sort of like a calliope, and it'll gurgle if you threaten it, but it's powered by compressed air instead of steam. The other instrument on the re cording was a Link piano. Link was a company in Binghamton, N.Y. that made a version of a player piano that included a full-blown marimba. The biggest player pianos were commonly used in bars or places of community gathering, where you dropped in a slug and got three, four minutes of mu sic. They're built like organs. They all run on air with perforated paper, parchment.

But LaVergne Smith's boyfriend played a real, steam-driven calliope? Where?

He played on the [river boat] Delta Queen. That's where he was playing then. These boats had pretty much disappeared by then. There weren't too many of them left.

You said this instrument's keyboard required so much force that it actually wore down his fingers.

His fingers really were stubby like that. They were worn down to the first knuckle.

Come on!

It was really true. You wouldn't believe it. They were shorter. He wasn't born that way, you could be sure of that.

You also recorded a New Orleans jazz performer named Wilber DeParis for Atlantic. Engineering other companies' recordings wasn't something you did much of, was it?

No. Very little. But that was stereo. It was important to do something in stereo for the 1952, I suppose it was. Audio Fair. And that was produced in binaural form.

One of your recordings was called Speed the Parting Guest. According to an item in The Audio Bucket, the idea for this was generated at a dinner party, and it was supposed to be a collection of jarring sounds-something someone could play "to get rid of a visiting fireman," as it was phrased there.

No, no. It was a percussive record, and we just called it Speed the Parting Guest because of the wild music. But it's music. They were all musicians playing instruments. The idea was percussion. The fellow that organized it was Jimmy Carroll, Mitch Miller's arranger. He was a good friend. The title came later. You know, what are you going to call it? God knows. So we called it, Speed the Parting Guest. But it wasn't a bunch of sound-effects men doing this, that, and the other. It wasn't supposed to be tongue in cheek. It was percussion--one of the things that is very difficult to reproduce.

And the record from Cuba, Jawbone of an Ass. An animal's jawbone was actually used as an instrument?

Oh, yes. Like a chac-chac, a gourd with pebbles. You rub a stick across the teeth.

One of your top artists was an English organist named Reginald Foort. Tell us something about him. When did you first record him?

1952. Reggie, after the war, had some what of a problem. During the war, the BBC had an organ in a couple of trailers, and he used to go around England giving concerts. It helped the war morale a lot. He was very popular. He was on the BBC constantly before the war as well as through the war, so his popularity was immense in England. Every body knew his name. But that faded.

You had him play in a number of places. Was the so-called "Mosque" in Richmond, Virginia the first?

Well, yes. The first job was in the Shriner's Temple, which really was just a rather large theater. I guess it seated a couple of thousand people. It had a working organ in it. It was being maintained by a fellow that worked in the telephone company.

You were apparently the first to record a 16-cycle organ tone. I believe that was with Foort in Symphony Hall, Boston. Didn’t even he tell you it couldn't be done?

That's right. I said, "Do it anyway," so he did. He was cooperative enough to do that.

And you really did get it?

Oh. yes.

But how many speakers of the time went down that far?

These did [indicates speakers at one end of his 35-foot listening room]. In the [Audio Fair] exhibit in '54, these were the speakers that were used. It was in a masonry room in the Hotel New Yorker.

These are the legendary Bozaks. What's in them?

Eight 12-inch woofers. You can't get more than eight without making the box bigger. Then it won't go through the door.

That's in the bottom cabinet [4 feet wide x 5 feet high x 21 inches deep]. What's in the enclosure resting on top of each one?

Two 6-inch midrange speakers and a tweeter cluster.

Right. Rudy's aluminum drivers. Someone who was at that show described standing in your room. He said he could feel the legs of his trousers flap.

The pedal frequencies were heard in the lobby sometimes-felt was more like it. It s not something you could resolve and say, "Oh that's an organ" or whatever, but it's strange how it would travel around the hotel and up and down the elevator shafts, then come out in the lobby. A feeling-no music, a feeling. It was perceived as something to alert you. It wasn't intended [laughs]. And it wasn't loud in the room. These things were played only somewhat louder than you would play them in your own living room. Because the room was full of people, you know. It was simply jammed.

Let me suggest something to you. Back in the early '50s, high fidelity was a novelty to most people, and the media was naturally curious. Not just industry press or buff press but general interest publications like Time magazine and The New York Times. Their writers came to the Audio Fairs and ran into a pair of real showmen, you and Rudy. They heard your recordings of trains and organs reproduced over his speakers. They heard stereo discs for the first time. Then they went back to their typewriters, described the experience, and got millions of readers interested in the phenomenon of audio. So maybe, just maybe, you and Rudy Bozak deserve a large part of the credit for making high-fidelity a house hold term.

Well, I don't think it was planned that way by anybody, including me or Rudy. It just happened that way because, I guess, it did sound good to people.

(adapted from: Audio magazine, Sept. 1989)

= = = =

Also see:

The Audio Interview: Tom Frost--Master Producer (Apr. 1991)

Link | --The Audio Interview: Jack Pfeiffer--RCA's Prince Charming (Nov. 1992)