HANDS-ON HISTORY

And I quote: "Imagine a museum in which almost everything works!" (This is from the June 1989 article by Peter Hammer in the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society concerning the John T. Mullin Collection of historical audio, as mentioned last month.) That is the very soul of the museum as it is conceived today--even including the art museum.

By "work" we mean that the object in question gives us a real and vivid idea of its own state of existence in its time.

Often this requires restoration. If the original involved motion--the phonograph record, for instance--then the museum's job is to give just that sense, one way or another. Today, the thing must "work," whether it is a painting, a locomotive, or a piece of audio equipment. You must have heard of the enormous flap over the recent restoration of the Sistine Chapel. Problems--there are always problems. But if you look at National Geographic, which showed the magnificent and brilliant results, you will understand that the "preservation" of older art exactly as is, until the stuff is barely intelligible due to time's destructive forces, is an idea that is over and done with. Almost. There will always be sticklers.

Luckily for all of us, they are losing ground. The modern type of museum is much more interesting. That's why I am promoting, as well as I can, a real national Audio Museum and Hall of Fame. Or the same by any other name, if you wish. It's bound to happen, sooner or later, and you may be sure that everything in it will work, as far as ingenuity and expertise will allow.

In my time (as we say when we get to a certain age), I have seen all too much of the opposite. In the early 1920s, when I was a child, I was taken to the Steinert Collection of ancient musical instruments at Yale. It was a typical 19th-century museum, a dingy, musty hodgepodge of all sorts of priceless old machines shown exactly as they had become, over centuries of neglect in assorted attics and cellars and back closets. There were harpsichords, clavichords, and virginals, blackened and decayed, with the remains of the strings hanging out loosely. The same for the rest. Just a musical dump, as I remember it. Even at that age, I was shocked-I already had discovered that I liked the sound of keyboard instruments even if I couldn't play them, and I was saddened to see these instruments in such disrepair.

Needless to say, that situation has since been remedied! (Editor's Note: See "Enduring Instruments: Treasures from the Yale Collection," written by David Lander and photographed by Robert Lewis, in the February 1989 issue.) I have a feeling that the harpsichordist Ralph Kirkpatrick was in charge of much of the long process of restoration that made this museum "work" in the musical sense. That 1920s jangling jumble of junk would be unthinkable today in any public presentation.

Yet in 1956, 30-odd years later, I paid a visit to the British Museum to pass away a rainy day in London. No doubt that worthy institution is still a scholars' mecca--it dates from the beginning of all museums as such, far back in the 19th century. But what I saw that day in 1956 was even more shocking than the music collection at Yale: Row after row, room after room of dingy, waist-high glass cases filled with what seemed a total mess-hundreds, thousands of bits and pieces of this and that, broken crockery, metal, who knows what. Unbelievable! No presentation whatsoever. Just collection. Yet it was open to the public. In comparison, the famous Louvre in Paris, also a vast repository of a million works of art, with paintings jammed together from floor to ceiling, still managed to convey a certain realness. The French touch. I enjoyed the Louvre! Or some of it-maybe 5%. After a few dozen rooms, if you have any sense, you quit. And go again another day.

Believe it or not, the idea of a "working" museum, a presentation, is relatively new. New in terms of history. In 1929, I visited Munich, Germany--before Hitler had made himself more than a local phenomenon-and instantly repaired to the Deutsches Museum, an absolutely incredible place where everything, everything, worked. If I am right, it was the first of its kind in the world. It covered just about everything German, from mining to music. I remember a whole segment of a working coal mine, through which you could walk or crawl. There were countless exhibits where you could press buttons and make things go, or have a try yourself at, say, a spinning wheel. For a kid this was heaven! My brother and I' spent days in that place, detaching ourselves from our father, who had business elsewhere. I remember nothing else whatsoever about Munich. My greatest thrill, in those many hours, came when I casually entered the music collection, and there were dozens and dozens of beautiful ancient instruments, meticulously restored and playable. Better still, you, the passerby, were allowed to try them out. That was the first time I ever heard the sound of a harpsichord, so common today. A few years later, I heard the first public recital on Harvard University's newly restored instruments. The "working" idea was spreading fast. I have not yet gotten over my youthful passion for the sound of these old instruments and each new advance. The fortepiano, the piano of Mozart and Beethoven's day, still has me enthralled.

All this, you see, is why I was enthused by the very idea of the Mullin Collection. It is indeed the prototype of what any larger, more public, and more permanently managed audio museum venture should be. Mr. Mullin has done it entirely on his own, as both the owner and the expert engineer and restorer. It's a sort of Murphy's Law in reverse--everything that can work, does. With the addition of a lot of large-scale exhibits, such as the broadcast studio scene I suggested last month, this is indeed our prototype for an up-to-date historical audio display--authoritative, operating impeccably, open to the public, and intended for the public as well as private scholars and researchers.

As for my own audio collection, covering approximately 60 years at this point, it is no better than the British Museum. Or, shall I say, the town dump near my Connecticut home. Indeed, the dump has long been a favorite visiting place for our resident population, and not merely to leave more junk. Those immense piles of flotsam and jetsam (whatever that is), those zany cookstoves sticking their legs out at 45° angles on top of heaps of old lawn mowers, broken shovels, hair curlers-you know the picture-are far more interesting and dramatic than was the British Museum in 1956. (Let us hope it is improved for 1990.) Also more visible, out in the daylight.

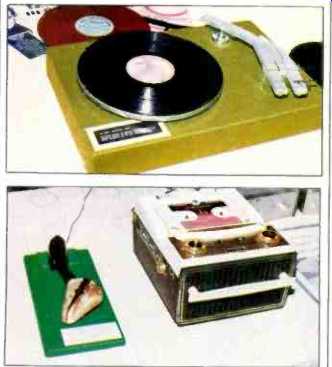

My own collection is awful, though I am not ashamed. I am no restoration engineer. You must climb up a rickety folding ladder into the attic to get near most of it, and there is only a crawl space, ill lighted, as you inch around the open chasm abruptly leading to the floor below. Back in the far corners, under the sloping roof, are "priceless" piles of expensive and once-state-of-the-art tonearms, unworkable turntables, half-eviscerated amps, and dingy speakers with notes stuck on here and there: ONE CHANNEL DEAD or TWEETER BUSTED. This entire heap of relics, someday, should be evaluated, pruned, and restored for that envisioned audio museum.

Actually, my real "museum" is in my head, sheer memory. I have been "restoring" a great deal of it in these columns over the years, and there's a new gleam in my eye as I look at the list of exhibits in the portion of the John T. Mullin Show (pardon me, Collection) which was bodily transported by the AES to New York back in 1988 for display at Convention time.

Hey, I played around with some of those myself! Imagine it. Maybe I can add some informal and un-museum-like bits of lore? Nothing like having your hands on a "working" piece of equipment, whether you are amateur, critic, or professional.

Indeed I've already described one item, the unthinkable Webcor (Webster-Chicago) Wire Recorder, and I doubt if any other living person can match my account of that utterly frustrating machine (January 1988). Jack Mullin has one. It works, we can assume, though it's hardly worth the trouble. If you read my account, then you'll see why.

Jack Mullin has the Old Original--in a more modern reproduction. I mean, the tinfoil phonograph of 1877. Could this be the spanking new phono that we sported on our cover for that celebrated 100th anniversary? Ask the Editor-he did it. (Editor's Note: Actually, the Editor didn't "do it." The unit pictured on that cover was a beautiful reproduction, made by Peter Hillman from a set of plans he purchased at the Edison Monument in West Orange, N.J. Hillman wrote a "review" of his unit, which appeared in December 1977, and when I talked with him a few months ago, he said he still had the model. -E.P.) In 1977, I visited the last Edison factory, now a kind of museum, and looked upon another spanking new exact replica, not the original. To my shock (as recounted here at the time). I then discovered the actual original, musty and covered with dirt, placed haphazardly in an inconspicuous corner, very much unrestored.

There you have the old museum versus the new! I sincerely hope that the Edison people have done something about that by now, 13 years later.

Do I have memories of the Victor Orthophonic Victrola! It was totally acoustic, 1926, but was designed with extraordinary expertise to accommodate the new electrical recordings then being quietly introduced (not to disturb the market too quickly). Everything you hear about that machine was true. For the time, its sound was unbelievable and indeed the very best on the commercial market. The earliest electronic phonographs were opposites of the older acoustic machines--all tubby bass and dismally lacking in treble.

The Orthophonic still had the treble, as good as it came, and thanks to an astonishing, folded exponential horn built inside the case, it had a range of bass that was startling after the tinny, older acoustic models, even the fanciest. (I can still hear that shrill little voice coming out of my uncle's big expensive console Victrola of an earlier year.) As previously recounted, we had several of these machines at the prep school I attended, and on them I learned the César Franck Symphony, the Brahms Third, and plenty more, playing them over and over again. I think I still hear them Orthophonically. I missed hearing Mullin's restored Orthophonic and would give my wisdom teeth, if I had some, for a good, leisurely listen. I'll bet it "works." Jack has a Vitaphone recording lathe, same year, 1926, used with 16 inch discs at 33 1/3 rpm for the first electrical talking pictures. I heard a very early demo of the Vitaphone less than a year later, in January 1927. It was held in a small improvised theater space at the New Haven Century of Progress Exposition of that year. I seem to disagree with some accounts of that pioneer film-to the best of my knowledge and memory it was old Fritz Kreisler, the hammiest violinist you'll ever see (and one of the best), who played the icky old potboiler "Humoresque" for Vitaphone. Whoever he was, it was a fat, leering figure that I saw on that screen, showing off like crazy as we looked at him and simultaneously heard him. The whole thing lasted only a few moments-maybe there was more that I forget. So, you see, I heard the very first public talking picture, not yet commercial, in prototype demo. Good start toward today.

Following on that, Mullin has a 1929 Western Electric Radio Transcription Recorder, reorienting the Vitaphone system toward "long play" radio material. Fifteen minutes a side. The speed and size were the same as Vitaphone, and we still have that speed today in the LP, though the ETs (Electrical Transcriptions) are now only in libraries. Or museums. My great exploration of early FM (in 1943 to 1946) found me in the middle of a huge rental collection of those ETs, both laterally and vertically cut, pressed on plastic, some of them on clear red vinyl. Far ahead of the 78 shellac! With the WE 9A reproducer head, wide-range vertical or lateral.

The ET reigned supreme in radio until tape came along. Indeed, there was even a brief spate of 16-inch, 33 1/3-rpm consumer long-play discs just before the LP appeared. Few remember this-the LP system was so much more suitable for home use and so ingeniously engineered that the big home discs vanished instantly. I might have one in the back of my attic.

I'll postpone a later miracle, the Cook "binaural" (i.e., stereo) discboy, did I try that system! It too vanished instantly in the face of the far more ingenious 45/45 stereo LP. Fun to play with, and Mullin has a working system; I have one disc. Must have sent the double arm back to the factory. Earlier, there was the fabulous Capehart console for 78s, automatic play. Everybody who was anybody (i.e., had cash) owned a Capehart because it was expensive, with rare woods, etc. It actually flipped the fragile 78s mechanically and only broke a few, in spite of many a legend. Rolls Royce? Infiniti? I saw, but never owned. Amen.

Jack Mullin has a Capehart, and it still works. Want some albums for it to chew up, Jack? I have plenty.

(by: EDWARD TATNALL CANBY; adapted from Audio magazine, Sept. 1990)

= = = =