by Robert Long

When Goddard Lieberson (1911 to 1977) first went to work at Columbia Records in 1939, it's doubtful that anyone could have fore seen the triumphs that lay in store for either the man or the company.

Lieberson was hardly the archetypal up-and-coming young executive, and Columbia's prospects for commercial greatness were even less encouraging.

--------- Lieberson began recording important …

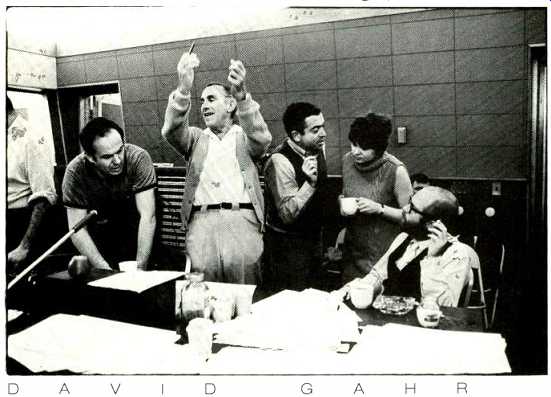

--- Goddard Lieberson with fellow Columbia producer John Hammond.

It was Edward Wallerstein who hired the 28-year-old composer to help him build the sort of artist and repertoire ("A & R") foundation Columbia would need to compete with the far more prestigious and successful RCA Victor Division, of which Wallerstein had been the general manager until the previous year. Lieberson, who had attended the University of Washington before entering the Eastman School of Music, had come to the conclusion that composing could earn nobody a living in Depression America and had been subsisting partly on reviews he wrote for Modern Music, though he had some 100 compositions to his credit already.

When those who knew him describe Goddard Lieberson, they almost invariably cite three characteristics: Charm, intelligence, and elegance, often in that order. "He would have been a member of the aristocracy in any civilization," one former Columbia employee said.

He also was a witty and resourceful polymath.

He had the ability to move gracefully among people and ideas and to manage both.

His abilities as a man- ager were to prove sterling both in the studio (as a producer) and in the executive office, where he eventually succeeded Wallerstein as president.

The talent acquired by Columbia Masterworks over the course of Lieberson's first decade there is a tribute to his talents and industry. The 1948 catalog listed the Metropolitan Opera, four major U.S. symphony orchestras, the Budapest String Quartet, at least five world-class conductors, and a score or more of major vocal and instrumental soloists, none of whom had recorded for U.S. Columbia before his tenure.

More important, perhaps, Lieberson had begun the recording of important modern works that was to give Columbia Masterworks a prestige boost that RCA's Red Seal could not match.

Among the most important were the Berg violin concerto with Louis Krasner and the Cleveland Orchestra under Artur Rodzinski and Schoenberg's Pierrot Lumaire with Erika Stiedry-Wagner. The latter recording was conducted by the composer, a pattern Lieberson was to follow with definitive recordings by Stravinsky, Copland, and Bernstein, among others.

Also important throughout his career were what might be called creative documentary recordings. An early example is the / Can Hear It Now set with Edward R. Murrow: Recreations of historic events, based on his radio show.

The finest documentaries were in the Legacy Collection book-and-record packages. The best remembered of these were probably those on the Civil War (The Confederacy and The Union), though Lieberson's favorite is said to have been Medicine, Mind, and Music.

Most of his early recordings were made on 16-inch acetates, rather than directly on wax or even acetate master blanks as had been the universal practice both at Columbia and elsewhere.

Use of acetate masters had begun about the time that Wallerstein arrived at Columbia. They had the advantage that, unlike wax, they could be played and checked aurally without serious damage should a question of the master's viability arise.

By 1940, Columbia was using 16-inch blanks running at 33 1/3 rpm and cut with a 3-mil stylus-electrical transcriptions (ETs), or simply transcriptions as they were called in radio.

Once the specific takes were cleared for issue, the acetates were dubbed to 78-rpm acetate masters for plating.

When a master was damaged, it could be redubbed; companies that stayed with wax had to either rerecord the side or dub it from a noisy pressing or a worn "mother" (the intermediate plating stage between the matrix and the stampers, from which records are pressed).

These technical details may not have interested Lieberson at first, but they were to prove crucial to his development as a producer. Wallerstein, on the other hand, had witnessed Victor's attempt to market a long-playing disc that revolved at 33 1/3 rpm. Like Edison's earlier long-players, Victor's bombed in the marketplace. Depression-era customers were unenthusiastic about having to buy a new player for these discs, even at Victor's cost-price of $9.95.

What was worse, for the classics at least, was that most of Victor's recordings were dubbed from the 78-rpm is sues, with obvious pauses every four minutes or so where the breaks be tween record sides occurred in the originals. And the heavy pickups of the era could destroy the surface of Vic tor's vinyl compound after only a few playings. This induced Wallerstein to withdraw the discs from the market in 1933 in his first official action as general manager.

Wallerstein seems to have been determined from the beginning that he and Columbia would succeed where Victor had failed, and a joint research project to that end-involving Columbia, CBS, and engineers hired away from Victor and GE-began almost immediately. Incidentally, the man who finally headed the project was, like Lieberson, a musician turned executive:

Peter Goldmark. Though Goldmark was often billed as the inventor of the Columbia LP, he did none of the actual development work himself, according to Wallerstein.

By 1948, following a hiatus imposed by World War II, the team had succeeded. Using an elaborate and recalcitrant mechanical cueing system, they could cut relatively seamless 12-inch LP masters up to 29 minutes long by assembling them from the elements they had been storing on acetate for the past decade. The fundamental difference between Columbia's LPs and Victor's discs was not only in their continuity but in the longer sides made possible by the finer (1-mil) tip radius of Columbia's Microgroove styli.

The opportunity for musical integrity unknown in earlier recording media would not be wasted in Lieberson's hands. In retrospect he often has been credited as a force behind in keeping development work moving forward. To what extent this view is an artifact of his later promotion of the company's triumphantly successful medium is now hard to assess, though his acknowledgment of the LP's importance to the Masterworks repertoire obviously was sincere.

In the meantime, he had begun the series of Broadway albums on which, more than anything else, his reputation as a record producer would rest.

Broadway albums as a genre had been created almost single-handedly by Decca Records (now MCA), but they still tended to be little more than collections of hit songs, sometimes not even sung by the original performers.

They seldom contained much sense of theater and rarely any of dramatic development. Lieberson was to change all that.

------- Lieberson began the change with drama. In 1944 he recorded Shakespeare's Othello in its entirety in the Broadway production starring Paul Robeson, Jose Ferrer, and Uta Hagen.

This was an extremely ambitious project for its time, but it would become the prototype for several other projects including recordings of George Bernard Shaw's Don Juan in Hell and Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot.

=============

Hail! (and farewell), Columbia

Sometimes designated the first record label because of the entertainment cylinders it issued, the Columbia label actually originated in the company's primary function, as sales rep for Edison dictation equipment in the District of Columbia. In the mid-1890s, it was already on its way to being a household name when Emile Berliner was still raising the capital to launch the Gram-O-Phone records that, as flat discs, were to put the phonograph cylinder out of the record business over the next quarter of a century.

The enterprises launched by Berliner soon became the Victor Talking Machine Company in the United States and the Gramophone Company in Europe. Their use of the wax-master technology (which actually de rived from Columbia's practices) and their energy in attracting major stars to the recording horn left Columbia, and the various corporate identities to which it belonged, playing catch-up by the time the world emerged from the First World War. In those palmy days, however, even a "me too" could turn a profit.

Then came radio. America was fascinated by its ability to hear people speaking, singing, and playing from hundreds of miles away with just the flick of a "cat's whisker" across the crystal, and record sales dropped off alarmingly. Victor was stunned. Columbia was very nearly done in.

It was at this time that Western Electric began demonstrating its electrical disc-cutting system to the Victor Company. Eldridge Johnson. Victor's president, was bitter about radio's competition and was loath to accept its electrical technology as a way out of his woes. While he temporized, and his subordinates fidgeted in the knowledge that the Western Electric system might get away from them, news of it began to leak out.

At Christmastide of 1924, Louis Sterling sailed into New York Harbor in search of a license to use the Western Electric system at his company, European Columbia. Western Electric declined, saying it would license only to an American company. Sterling agreed and bought a controlling interest in Columbia Graphophone to act as his intermediary.

The ties between the European and American Columbia labels, which lasted beyond Sterling's ownership of the latter, netted it an infusion of major classical recordings, some of them phonographic firsts of now-revered modern scores, and a good deal of Middle European dance music of interest in U.S. ethnic markets. But they bolstered its prestige more than its solvency. Sterling had paid $2.5 mil lion for his interest, which was sold again in 1931 to a company that was broke by 1934. The American Record Company was able to pick up Columbia at that time for a mere $70,500.

In 1938, Edward Wallerstein persuaded William Paley, the CEO of the Columbia Broadcasting System, to pay $700,000 for the record company and install Wallerstein as its president.

At some 10 times the previous selling price, that may not have been a bargain, but Wallerstein knew that the lessons he had learned from the technical and marketing mistakes imposed on him by RCA during his years at Victor could be turned into advantages at Columbia.

Building on the foundations laid by Wallerstein, Goddard Lieberson saw the Columbia label into an unprecedented era of prosperity as a titan (some would insist, the titan) of the industry. He put Mitch Miller in charge of the pop wing, which proved as sensationally successful as his own Masterworks offerings. The Columbia catalog, and the pre-emptive success of Columbia's LP, allowed it to cast a shadow across RCA Victor that had never before been possible.

Following the difficulties of the Clive Davis administration, Lieberson came out of semiretirement to reassume the helm at Columbia Records, but the times were already changing, and things continued to change. Even the company name is changed today.

Columbia Masterworks is gone; hail, Sony Classical!

-----

=============

---

--- From The Apple Tree, Lieberson (second from left), Jerry Bach (middle),

and Barbara Harris (second from right).

Since Lieberson was the director of Columbia Masterworks, these discs appeared on the Masterworks label.

According to Didier Deutsch-a producer and annotator for the Sony Broadway reissue series-the label next recorded excerpts from the 1946 revival of Jerome Kern's Show .Boat.

That also was a Masterworks release and, though not officially a Lieberson production, evidently convinced him he could compete on Decca's turf, as well as Red Seal's.

The following year, the Broadway producers of Finian's Rainbow came to Lieberson. Decca had refused to take the show as a package, preferring to exercise its habit of substituting house artists wherever expedient. Would Lieberson buy it as is? He would and did, spreading his unusually complete musical coverage over six, 10-inch records and catching the flavor of the stage production with exceptional panache. Kurt Weill's Street Scene, also recorded in 1947, ran to six, 12-inch discs. As an ensemble show, rather than a stars' vehicle, it was a particularly startling choice for such lavish treatment.

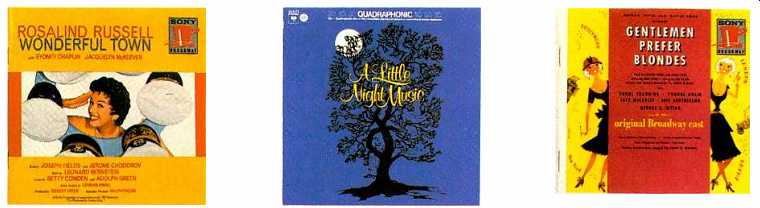

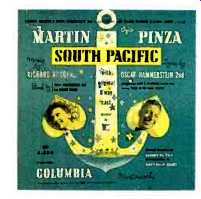

Rodgers & Hammerstein's South Pacific, in 1949, won Lieberson his first Gold Record and his golden age was properly launched. In 1950 came his first "recreation": Cole Porter's Anything Goes with Mary Martin. There were four show albums that year and five the next. The count would stay at least that high throughout the '50s.

There were two projects of 1951 that deserve special mention. For Noel Coward's Conversation Piece, Lieberson had Coward write rhymed couplets to serve as narration but kept much of the dialog of the main characters, as well as the music. This permitted him to suggest the Regency setting and retain most of the play's action, in a sense, translating a very stagy stage work into phonographic terms. It was literally "produced for records" as no show had been before.

Even more brilliant was his production of George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess. He chose Camilla Williams (one of the first black stars of the New York City Opera) as. Bess, and Laurence Winters (also a member of that company) as Porgy. Under Lieberson's direction, Avon Long's breathy crooning as Sporting Life was captured in "close ups" that co-existed comfortably with two principles.

When the crap game begins, the listener finds himself on the stage and within the eager circle of players, hearing every click of the dice. The fight that ensues is observed from a barely safe distance. Lieberson used the microphones as a film director might use his camera, moving in and out of the action as each moment demanded.

The closest parallel to this technique at the time was to be found in radio. At CBS (of which Lieberson was once a vice-president), radio drama had been given new depth and meaning by such writers as Norman Corwin and Arch Oboler--and Orson Welles, whose War of the Worlds dramatization on CBS caused a national panic. It was called "theater of the mind." To what extent Lieberson may have heard and been inspired by radio is impossible to tell, but the similarities of technique are undeniable.

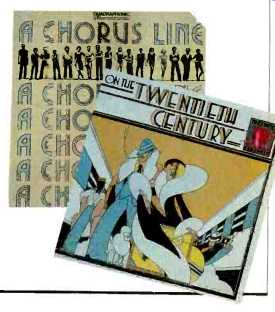

Another project that, like Street Scene, is a darling of Broadway collectors is The Most Happy Fella of 1956.

Although Frank Loesser stayed within accepted musical-comedy style in most respects, the sheer quantity of his music and the way it contributed to dramatic development were quasi-operatic. How was such a show to be treated on records? Lieberson's answer was to record it essentially complete on three LPs. Porgy had required that much space, but Porgy had full scale operatic recitatives where Fella relied on accompanied dialog. Lieberson retained the essential dialog and, with it, an exceptional feeling of the stage.

According to those who worked with him, Lieberson actually avoided spoken dialog wherever possible, believing that it would not wear well in repeated hearings. Just as he had no qualms about padding out the pit band for a fuller orchestral sound in the re cording-even adding chorus parts to the opening of A Little Night Music, for instance-he conceived all facets of these productions as translations to the phonographic medium. His function in the recording studio therefore was analogous to that of a movie-studio production team that must translate a book or play into cinematic terms.

The importance of this approach cannot be over-emphasized. He was perhaps the first producer to under stand fully that the phonograph record is a unique medium of communication.

It can, and should, in most instances, make reference to the values of the theater, concert hall, movie soundstage, opera house, or lecture hall. But the intimacy that exists between the recorded performance and the listener at .the moment of listening makes it unlike any of these. Of all audio media, only radio comes close, but radio is produced essentially for a single hearing at the broadcaster's discretion.

Records are an on-demand sonic medium controlled by the listener.

In tailoring a Broadway score to the opportunities and constraints imposed by that view, Lieberson's practice was to begin watching and timing the musical numbers before the show even opened, according to composer Elizabeth Lauer. She was his secretary and, later, associate producer in the late '50s and early '60s. In the end, Lieberson sent her to tryout performances to make these initial findings. On the basis of these findings, he would develop his plans for translating the show to the phonographic medium.

-----------

=====================

Lieberson's Broadway Revisited

Goddard Lieberson's Broadway musical and operetta discography runs to some 40 recordings and remains his most significant achievement in the studio because of the way his qualities mesh with these recordings. It's therefore no surprise to find that they constitute the bulk of Sony Classical's first reissue release in its Sony Broadway series-nor is it a surprise that Sony expects to issue most of his list as the series continues.

The remastering, using Sony's 20-bit digital technology, is directed by one of the project's two producers Didier Deutsch and Thomas Z. Shepard. They go back to the best avail able material, which in some cases may be the original studio tapes rather than the equalized and mixed master tapes from which the original LPs were cut. CDs' longer running times permit the inclusion of material that was omitted from the original issue because of time constraints, and since Compact Discs don't have to be turned over, Sony can revert to the show's actual musical sequencing, whereas the LP break dictated a different order.

The Sony Broadway project is expected to take years to reissue all (or almost all) of the shows in the vault some of them rarities that, precisely because they were not blockbuster hits in their time, may be of the greatest interest to collectors today. In this category are two 1962 Lieberson productions: All American (Charles Strouse) with Ray Bolger, Eileen Herlie, Ron Husmann, Anita Gillette, and Fritz Weaver, and Mr. President (Irving Berlin) with Robert Ryan, Nanette Fabray, and Anita Gillette.

In addition to two recordings not produced by Lieberson, the first CD releases included:

The Most Happy Fella (Frank Loesser, 1956) with Robert Weede, Jo Sullivan, Art Lund, Susan Johnson, and Shorty Long; S2K 48010 (2 CDs).

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Jule Styne, 1949) with Carol Channing, Yvonne Adair, Jack McCauley, and Eric Brotherson; SK 48013.

A Tree Grows In Brooklyn (Arthur Schwartz, 1951) with Shirley Booth, Johnny Johnston, Marcia Van Dyke, and Nathaniel Frey; SK 48014.

Miss Liberty (Irving Berlin, 1949) with Eddie Albert, Allyn McLerie, Mary McCarty, and Ethel Griffies; SK 48015.

Candide (Leonard Bernstein, 1956) with Barbara Cook, Max Adrian, and Robert Rounseville; SK 48017.

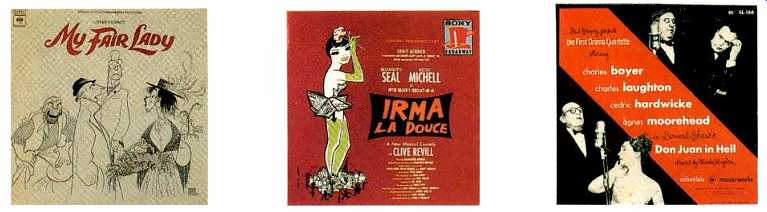

Irma la Douce (Marguerite Monnot, 1960) with Elizabeth Seal, Keith Michell, Clive Revill, and Elliott Gould; SK 48018.

(All are available on analog cassette as well, with ST prefixes instead of SK prefixes.)

=====================

Thomas Z. Shepard, who also was hired and, to some extent, groomed by Lieberson (and was later to be both a director of Columbia Masterworks and an outstanding producer of Broadway cast albums) remembers his manner in the stud o as suggesting, much more than demanding, the performance values he hoped to get from the cast. He could be scathing when pushed to the limit, but his gentlemanliness was hard to dent under other circumstances.

Lieberson's apparently inherent theatrical sense came out, Shepard believes, in the way he might suddenly be "inspired" during the session to change something in the interests of a more telling phonographic product, even when it seemed evident that he had planned to make the change all along. It was his exceptional self- awareness that led him to be "on stage" much of the time.

Once the sessions were over, he generally left the post-production to other hands. In the '50s, that meant primarily editing and possibly equalizing the tapes before mastering. Mixing became a standard technique only after the introduction of stereo. Teo Macero, who did the post-production on most of Lieberson's Broadway recordings, is afforded an important share of the credit for their success by those who were around at the time. Lieberson remained in charge and might send the product back to Macero for yet more polishing, but Macero did the actual work.

When Lieberson became president of the record division, he felt it a bit unseemly to continue producing.

Worse, his limited time in the studio meant that he would have to play favorites among the available shows and inevitably bruise egos. But, Didier Deutsch says, having built Columbia into the most important original-cast label, he continued to exercise control even when his name did not appear as producer.

This was a business decision as well as an artistic one. The two considerations were intimately connected, be cause Lieberson induced Columbia to invest in shows as a way of securing recording rights. Columbia is believed to have been the first to offer some form of cash outlay in return for the recording option, as early as Finian, and the pattern grew steadily until 1956, the year of My Fair Lady. Lerner and Loewe had been unable to find backers for anything as outré as a musical version of a Shaw play, so Lieberson got Columbia to act as sole "an gel"--for $360,000, a hefty tab back in those days.

So great was the undertaking's success that Lieberson had carte blanche from that time on. But he ultimately came to regret the financial involvement in the shows themselves. Ac cording to Lieberson, show business and the record business are separate entities with separate priorities that should be pursued independently by specialists in each.

Incorporation of the show albums into the Masterworks catalog was one reason for the outstanding bottom line of the label, whose growth after Lieberson took over was unparalleled among classical labels of the time. For this reason, Lieberson became a sought after interview subject among business reporters--a role he truly savored. He was fond of saying that being a musician required a kind of intelligence that is easily converted into executive skills, but that trying to convert an executive into a musician has far less chance of success. This delighted the reporters and became a staple of the Lieberson executive persona.

Both Tom Shepard and Elizabeth Lauer were beneficiaries of Lieberson's attitude. He chose her as his secretary over her own objections that her stenographic skills were inadequate for the task. Actually, he as signed the routine work to others and relied on her for the subtler skills of a "gal Friday." And he hired Shepard (a composer as well as a producer) "off the street" to become a producer de spite his lack of extra-musical qualifications.

Shepard remembers that a battery of tests was required before he was accepted, so it seems that Lieberson did not rely on musical intelligence alone.

It has even been suggested that Columbia later fell into decline precisely because Lieberson failed to remain true to his principles in this respect.

According to one colleague, as division president, Lieberson turned over more and more power to the psycho logical testers, to accountants, and to lawyers, distancing himself and the division ever farther from his creative roots.

That Lieberson's pre-eminence might have aroused jealousy among those around him must be admitted.

Still, it is hard to find evidence of it even among those on whose work Lieberson relied but to whom official recognition might be denied. Yet, he could be ungenerous to others-in both credit and remuneration-and as president seemed unwilling to believe that others could do things as well as he. Had he been less charming and less of "an enormous force for the good," as one employee put it, more voices might have risen in dissent.

Perhaps a certain ruthlessness is a necessity of any creative personality, and Lieberson's creativity is beyond question. No producer in the history of the medium has had a more profound influence on what we can hear on records because none before him was so keenly aware of the unique relationship that exists between records and those who listen to them.

Walter Legge (the doyen EMI producer from the 1930s to the 1950s) disparaged the work of his predecessor and sometime boss, Fred Gaisberg, on the ground that Gaisberg simply let the artists loose in the recording room and took "aural snapshots" of whatever they did. Legge himself strove to create the ideal performance of the music at hand and pickle it, so to speak, for all time, imposing his "definitive" view on artist and listener alike.

Lieberson's approach implied more respect for both. In place of Legge's almost disembodied ideal he created a very specific sonic reality that could be as much a work of production artifice as of musical art. What was ideal in the abstract, he realized, might be far from ideal in the listening room. In the final analysis, the integrity of the listening experience was his sole criterion, his legacy.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Sept. 1992)

Also see:

Listening and Experience (Aug. 1992)

= = = =