by EDWARD TATNALL CANBY

SILVA NUGGET

This last spring, on my annual vacation, I very nearly gave my all to Audio, though it was perfectly safe. I do not like heights. You know the feeling! And there I was, walking, almost crawling, across a 3-foot-wide catwalk of steel grating about 200 feet (that's the way it looked) above the floor of a new concert hall, the tiny seats all too visible straight down between my shoes. At first I flatly refused-but this was no ordinary hall and duty called, so I did it, Oof! I keep saying, never again. But it was worth the torture, for here was the first hall ever to be built from the start with electronic acoustics as part of the basic design. And the "works" of that system, alas, were up on the catwalks.

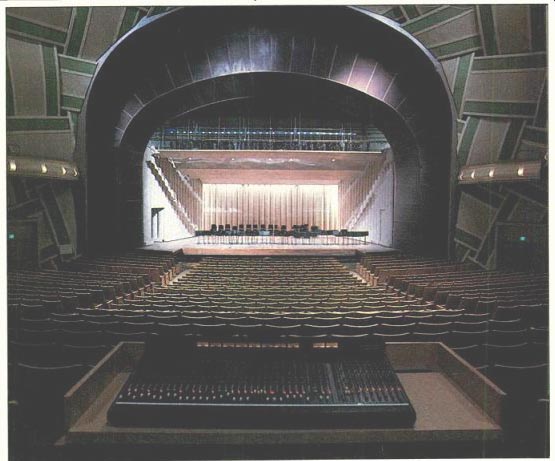

Silva Hall in Eugene, Oregon, just happens to be visibly, and structurally, the most startling example of new hall architecture anywhere around right now-it has already become world famous since its opening last fall. Every year I seem to run into something new in that enterprising small city on my visits to its Oregon Bach Festival.

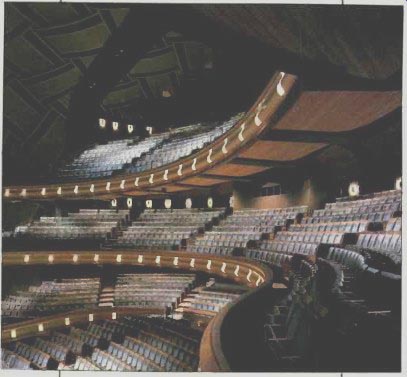

This year the festival was held mainly in Silva Hall. I caught a glimpse of the inside of this hall two years ago-nothing but dreary concrete walls and floors joined by rickety ladders-and again last year when the basic insides and out sides were in place, though not the stage. What was once the Eugene Performing Arts Center is now the Hult Center, thanks to a large last-minute gift, and the bigger of the two enclosed spaces is Silva Hall. As a music listener I can tell you that it is the most exciting, refreshing place to hear mu sic, almost any sort, that I have ever been in, absolutely unlike any other, all rococo lightness and humor. The huge external lobby is an airy assemblage of incredibly tall, peaked roofs in wood and glass, touched up inside with lofty balconies at many levels joined by stairs (and an elevator) paved in apple green floral carpets. The hall itself is a basket, inverted-you are inside a rounded basket-weave shell, the bands of material literally woven criss cross at the diagonal (some absorbing, some reflecting) like some huge party basket with ribbons, the whole again in deliciously frivolous shades of fresh green, mint and watercress. The three balcony fronts (one an extension of the floor itself) snake back and forth in compound curves, each different; the high seats are warm-blonde pressed wood with green cushions the audience is a sea of heads.

What a pleasure at intermission to go from the subdued but warm lighting of the hall itself out into the high, brightly lit lobby, fresh aired, friendly, decked with people on many levels above and below. In daylight, the sun streams through multi-pasteled glass; at night, colored tubes light the peaked structures. Intermissions go on and on such gab sessions you never heard.

Several large refreshment places serve everything from hamburgers to glasses of champagne. It is concert heaven, even if a good many of the older, wealthier inhabitants of Eugene do not much approve. After all, shouldn't a concert be dignified, i.e. stuffy and formal? These are the folk who go to sleep with the first notes of the music and wake up to applaud mightily. They subscribe to every series and go to all the events, too. They don't really like all this fresh informality. I do. So will plenty of others.

I cite these visible attributes be cause a concert center is for live sound, and the sound must match the intentions, the visibilities, of the hall it sell-. Without its electronics, Silva Hall would be useless-it is so designed. It depends deliberately on the immensely 'sophisticated electronic assistance that helps the hall itself produce its own sound and indeed, a far wider range of sounds, types of music and entertainment, that could ever be achieved acoustically. And this at a cost, assuming the electronics work out, which is far less than an equivalent mass of adjustable panels, curtains, hanging reflectors, and all the rest of the paraphernalia which has been developed, not without many a failure, since WW II.

We are thus at a new cutting edge. Ours is an age where music of wildly different sorts and periods must some how be brought viably to audiences far greater than ever envisioned before.

We cannot build separate halls--Baroque, Classic, Jazz, Chamber Music, Opera, Big-Band & Rock, Solo Recital, each with its own size and sound-and then run every show on successive nights (as the Eugene Bach Festival aid in the old and right-sized Beall Hall, seating 500: in order to accommodate everybody! What we must have is overall, general-purpose centers, with no more than perhaps two sizes of hall (Hult has two) to cover everything in sound. This has been the goal since the 1930s, and it never was met with much success. The change able, physically adjustable hall, once so promising, has not worked out. Too often everything is compromised, nothing sounds really right. Mil lions of dollars, pounds, what ever, have been spent on costly, painful revampings, notably the immense Lincoln Center complex in New York, where Avery Fisher Hall (ex-Philharmonic) has had two near-total re-buildings.

If I may say so, the electronically assisted hall is to the all-acoustic general-purpose space as the digital CD is to the LP. The things we now ask the LP to accomplish, like four channels, automatic operation, silent back ground, and so on, it does do, but inadequately; the digital compact disc takes to the same like the usual duck to water and offers huge future flexibilities too. The old con cert halls, marvelous in their day, are still marvelous for what is now a limited, restricted use. We have hundreds of them, worldwide-splendid for re cording, too. And we have the "new" old-type halls, running on acoustic power, modernized, and all too often inadequate. There are indeed a few halls electronically assisted after the fact-and one (to date) brand-new hall designed for the new age, acoustics and electronics intimately combined.

Silva Hall.

It may never work perfectly without fixes and it doesn't yet. Even the operators are new to the concept and must learn plenty. But the future, if we continue to enjoy kilowatts of a.c. minus missiles, surely lies right here. Isn't ours the age of electronics?

Of course, you want to know the de tails of this Hult Center system in Eugene and you will find them in recent technical articles, both in architectural (Architectural Record) and in sound engineering journals. After three weeks and a dozen or more classical concerts of every sort in Silva Hall, plus a tour of the inside works, I know some thing first-hand as to how it all operates. My best function is to look at the phenomenon from outside, to give you an idea of the audio importance of this development, a whole new major division of audio art-and the sort of effect it has on (a) audiences and (b) on the performing musicians themselves.

The reactions are remarkable, mainly in that practically nobody (save a few scientifically interested souls) pays the slightest attention to the electronics. The audience ignores the whole thing and speaks of the hall like any other. The musicians, so to speak, en joy the publicity, the warm response to their playing, but complain (rightly) of a certain lack of two-way response; they do not feel enough a part of the audience in the sound they themselves hear. The town music critics studiously avoid any mention of other than musical performance-it is their tradition, of course, to keep things like hi-fi, records and all electronics on a suitably lower plane than the Real Thing, live music. In all these reactions, then, the performances are judged exactly as if the natural hall sound was all that was heard. Oddly, this is good. It is in fact necessary as a start. But I found it often exasperating.

In fact my ceaseless questions really got me confused-did conductor Helmut Rilling deliberately play down and soften and make distant the opening of the Brahms Requiem, or was the electronic system wrongly set or misbehaving? I could not get any intelligible answer. It was perhaps some of both? Good, actually; and indeed it is difficult to discern any concrete, direct effect of the hundred or so hidden loudspeakers in that hall, as distinguished from the live sound supposedly coming from the stage. Very good! But also very revolutionary, as you may begin to understand.

This is no mere sound system, even state-of-the-art, though there is such a system on hand, with a speaker cluster that will blow your musical pants off if that's what you want. They also do rock shows and musicals and pop stuff here, remember, as well as harpsichord solos by Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach. This (basically independent) system was used in the Bach Festival concerts mainly as a very gentle accent for soloists, if I am right, and to boost the harpsichord just enough so it would carry to the far balcony, faintly (as is proper) or be heard solo against an orchestra of 20 or so players. But even here there was innovation. Instead of the usual solo mike, there was a flat black spot on the floor, at the end of a long snaky cable--a Crown PZM. Set well in front of a soloist or even groups of three of four, or mounted low next to the harpsichord, it did unobtrusively what PZMs can do and failed only once--when a slightly rattled violinist stood much too far away.

There are no close-up mikes in the two main electronic assistance systems which work together in this hall though on very different principles. All sound is picked up at a distance as hall sound. This is not sound reinforcement, it is hall reinforcement. Let me circle in a bit closer. What I like to call the primary system is AR--no, not Acoustic Research (have to do some thing about that) but Assisted Resonance, out of England. It is not new; it began in the celebrated Festival Hall in London, rescuing that foundering acoustic from sure doom. Other halls in the U.S. have been revamped to improve their ailing acoustics, or are in the process of extensive face lifting.

Eugene's AR is the latest and most daring application, via a new building designed for its use. In Eugene there are-so you'll see what's involved--no fewer than 90 microphones in the main AR array, all of them mounted high up in an arc at the top of the hall on one of those dizzy catwalks (the ribs to the basketry). They feed-more properly, feedback-into an equal array of 90 smallish loudspeakers set out on an other catwalk high over the edges of the balcony.

These mikes hang a foot or so apart on dangling chains, all across the cat walk. You can lift them up to look at them, then dangle them back into space. They are no ordinary mikes.

Every one is inside a tube, a tuned (Helmholtz) resonator, various sizes, each responding to an extremely narrow range of frequencies only a few Hertz wide. Indeed, they are remark ably like organ pipes in reverse, though the array is deliberately random, apparently so that no fixed directionality will be observed in the output.

These mikes feed their controlled resonance (feedback) in pairs to half as many preamps, the levels extremely critically adjusted to avoid real or un controlled feedback, i.e. howl and squeal. The total frequency range covered is remarkably small, only upward to some 1.2 kHz if I read right, this being the area of greatest definition in musical sound. Not far downwards either; we all know that low bass just rolls around any old way. I assume the two-into-one preamps are a useful working compromise, saving on complexity.

Each preamp feeds out to a pair of speakers, which receive nothing but two highly resonant bands of narrow sound-no doubt unintelligible as mu sic. But, by adjusting the levels, the die-away time of every frequency can be set independently of the others, to alter and extend the hall's own physical sound in extraordinary detail. And this is only one of the three systems in use! Space is up--I'll get to the associated EKES system, very different, and to some of the concerts I heard and comments thereon, in a later follow-up. But do you already perceive a major new dimension in audio? And maybe a new industry, too?

(adapted from Audio magazine, Oct. 1983; EDWARD TATNALL CANBY)

= = = =