by Martha Sanders Gilmore

THE BEST THING the Kennedy Center on the Potomac has going for it are its superb acoustics, which performers and critics alike warmly praise, though the building has also been acclaimed for its beauty. The structure takes shape in a majestic rectangular slab of white Carrara marble, some 3700 tons cut to specification and donated by the government of Italy. The marble is the largest of the gifts the Center received from foreign countries. The Kennedy Center sits on a 17-acre tract of land, a classic Greek temple in stark contrast to the tangled wilderness of Theodore Roosevelt Island near the opposite bank of the Potomac. Architect Edward Durell Stone said of the site: "It is one of the most exciting and glorious settings for a public building in the world." From atop its expansive roof, the Jefferson, Lincoln, and Washington Memorials loom historically in its panoramic view. And underneath its roof are housed three separate theaters: the Concert Hall, the Opera House, and the Eisenhower Theater, separated by a Hall of Nations and a Hall of States, colorfully blazoned with their respective flags.

Although ground was broken on December 2, 1964 for the $68 million structure, which seats 6500 persons, construction did not begin until 1966.

A succession of American Presidents had a hand in its formation. On September 2, 1958, President Eisenhower signed the National Cultural Act into law.

President Kennedy signed amending legislation extending the deadline of fund raising for three years, to give "full recognition [to] the place of the artist." After Kennedy's assassination, President Johnson signed into law a bipartisan measure designating the National Cultural Center the only official memorial in the nation's capital to the late President Kennedy, renaming it the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

The person responsible for the remarkable acoustics of the Center is Dr. Cyril Manton Harris, who holds dual professorships at Columbia University while serving as a consultant in the acoustics field. Harris, a "fireball of energy" according to his June 17, 1972 profile in The New Yorker, maintains a rigorous schedule at Columbia, wasting not a moment's time out of his beautifully organized schedule which is as firmly packed as canned sardines. Prof.

Harris' regimentation is necessary to carry out his duties teaching acoustics in both the School of Architecture, where he also teaches a course on the legal and technical aspects of noise control with Prof. Albert J. Rosenthal, and the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences.

Harris received his doctorate in physics from M.I.T., studying under Prof. Philip McCord Morse. The author of numerous scholarly articles in the acoustical field, Harris is editor of The Handbook of Noise Control, published in 1957, and has compiled a Dictionary of Architecture and Construction, published this year. Having always been interested in electronics, Harris is the co-inventor of a talking typewriter. In view of Dr. Harris' auditory accomplishments, it may not surprise you to learn that he has such exceptionally acute hearing that he has to wear earplugs to get a good night's sleep.

Cyril Harris has served as an acoustical consultant for years and is presently working as an architectural-acoustics consultant specializing in large auditoriums. He planned the acoustics for Powell Hall in St. Louis and we have him to thank for the acoustic design of the new 3850-seat Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center. It was in this capacity that he collaborated with architect Edward Durell Stone in the design of the three magnificent performing halls at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. The Center's first use and grand, glittering opening in the Opera House on September 8, 1971 was attended by members of the Kennedy family and other carefully coiffed celebrities. They heard the world premier of Leonard Bernstein's Mass, commissioned specifically for the occasion--a controversial work to launch a controversial Center.

The Center's resident orchestra, the National Symphony, conducted by Antal Dorati, opened the Concert Hall on September 9th, while the Eisenhower Theater threw open its doors October 18th with Ibsen's Doll's House, starring Claire Bloom.

Dance was one of the strong-points of the inaugural season of the American Ballet Theater. The Kennedy Center's resident company, the Alvin Ailey Company, and companies came in from all over the world to dance on the Opera House's highly praised stage. In addition, there were 87 concerts by 22 major world orchestras; 46 concerts of jazz, folk, and rock; a House of Sounds Jazz Festival and American College Jazz Festival; 34 recitals by world-famous individual musicians, and 36 weeks of theater.

The Kennedy Center is young and a point in its favor is that it has fostered healthy competition among Washington area theaters in getting suburbanites into the city and away from TV. And despite the vitriol spouted concerning Center tactics and the occasional caustic reviews of individual performances, the commentary on the Center's acoustics have been virtually free from attack.

Music critic of The New York Times, Harold C. Schonberg, who attended a rehearsal before the opening, commented with enthusiasm upon the orchestral sound of the National Symphony in the nearly empty Concert Hall.

"The sound was reverberant and full, with a stunning bass quality and unusual `presence.' The various choirs of the orchestra stood clearly apart from each other, but there was a voluptuous mesh.

Indeed, there was no feeling of listening to music in an empty hall. The sound was `tight' and echoless, without the feeling of being in a barn that is experienced at so many rehearsals in unoccupied auditoriums. There even seemed to be no loss in quality under the balcony overhangs." Washington Post music critic Paul Hume cited the Concert Hall acoustics as "a modern miracle" and praised the hall's "clear, balanced, live sound." Martin Feinstein said exuberantly: "We have been blessed! We haven't touched the halls since they've been opened. Audiences are happy. The critics are happy, and more important, the artists are happy. Every artist I have talked to has raved about the acoustics in the Concert Hall-Artur Rubenstein, Isaac Stern, Beverly Sills, Dorati, Normandy-all praise the acoustics, and they are remarkable. The same is true in the Opera House. Even for a straight play. Ingrid Bergman was very happy with the Opera House in spite of the fact that it is a big house for a straight play. The New York City Opera came down here and they were just bubbling over about the acoustics in the Opera House. And the same thing is true in the Eisenhower Theater. Cyril Harris has batted 1000, which is unheard of," Feinstein laughed.

There have been, however, a few minor grievances by some performers concerning the difficulty of hearing onstage, especially in fortissimo sections, and another Washington Post critic, Alan Kriegsman, insists the Concert Hall doesn't live up to "its paradigm in Boston." Paul Hume recently commented on the audible transmission of coughs and whispers and those Concert Hall doors which close with a bit of a bang when people simply must get up during a performance. (The doors reportedly have been since worked on.) This writer has noted a certain shrillness in sound quality as though the hall is almost too sensitive. Noticeable also is a tendency for the percussion instruments-except for the piano-to override and sonically smother their fellow instruments so that (at jazz concerts in particular) it is often necessary to place a pad or shield in close proximity to the drums.

But, for the most part, these are minor flaws, and there is talk of recording in the Center's halls for all their clear, lively, well-balanced sound.

Dr. Cyril Harris summarized: "It came out exactly as we planned it." Harris actually began work on the project as early as 1965 in close consultation with the architect and engineers, thereby getting the jump on problems and preventing them by superimposing acoustical principles upon Stone's design from the very outset. Harris says: "Acoustics is a science. Applied acoustics is both science and art-the application of experience to the science . .

Dr. Harris encountered very special problems in the acoustical design of a Center for the Performing Arts beset by the traffic noise of a neighboring parkway and in the direct flight path down the Potomac River of low-flying jets coming in for a landing at nearby National Airport, directly downstream from the Kennedy Center. Helicopters at times hover about the Center like gigantic mechanical bumblebees. Harris notes the Center "posed some unusual and severe problems in acoustical design because of exceedingly high peaks in the background noise level." It was therefore crucial to insulate the Center from all extraneous noise sources.

Dr. Harris describes the Center's construction as a "box-within-a-box" wherein the three auditoriums are insulated from noise by individual supporting columns completely independent of the columns supporting the outer framework of the Center. This tactic also protects the theaters from noise of facilities such as kitchens and cafeterias directly over them. In most cases, Harris implemented solid 6-in. high-density concrete block double walls separated by a 2-in. airspace filled with low-density fiberglass laid on load-bearing cork, and used sound rated doors. In each instance, noise rated doors are used for auditorium entrances and each auditorium is enclosed by corridors at each audience level to prevent noise from pedestrian traffic in and out of it. Described as "sound locks," the theaters have acoustically treated ceilings, their walls are covered with 2-in. thick absorptive acoustical board faced with carpeting, and their floors are covered with carpeting.

Separating each of the auditoriums are the Hall of Nations and the Hall of States, two enormous halls through which ticket-holders pass to reach the individual theaters. Forty feet wide and 63 feet high, the halls run all the way from the front of the auditoriums to backstage. At intermission, theatergoers gather in an additional hall of gargantuan proportions, the Grand Foyer, one of the largest rooms in the world. An awe-inspiring promenade 600 feet long, 40 feet wide and 63 feet high, the Grand Foyer flows down the entire length of the Center in front of the three auditoriums with its west side flanking the river. Along the west wall is the 7-ft., 3000 lb. monumental bronze head of the late President Kennedy sculpted by Robert Berks. The Grand Foyer creates another potential noise problem in that the audience from one performance often stands around in it chatting while another theater is in operation. Air traffic noise is also a hazard in the Grand Foyer. Therefore special sound considerations were required such as carpet on the floor underlayment, acoustical plaster on the ceiling, and a total of 40 sound-absorptive panels on the walls. The side of the Grand Foyer overlooking the Potomac is glazed and large acoustic double window units seal out air traffic noise as well as providing thermal insulation.

Both panes of glass in each unit are "mounted with a resilient seal so that there is no solid connection between the glass and the surrounding frame." The noise from the air-conditioning system was a factor in Harris' overall acoustical plan and by consulting with architect Stone and the engineers in the early stages of construction, a noise level of no higher than NC-20 was insured throughout the stages and auditoriums, and all transformers and mechanical units were strategically placed to the advantage of noise control. Cyril Harris lists other noise-control measures as " . . . specifications which limited the noise output of potentially objectional noise sources, and the appropriate use of floating slab constructions, inertia blocks, resilient mounts, flexible connectors, duct lining, damping materials, and sound traps, as required. Where noise from piping was a potential problem, flexible connectors and resilient hangers were used. Finally, where space requirements were such that it was necessary to locate a quiet area under a mechanical equipment room, a resiliently hung ceiling was used in that quiet area." The Concert Hall, the largest of the Center's auditoriums seating 2,759 persons, is a rectangle and is similar in shape to some of the finest concert halls in the world such as the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the Musikvereinsaal in Vienna, and Boston's own Symphony Hall. Because of the decorative embellishments of gargoyles and cherubs, indicative of the time when these halls were built, they provide excellent acoustical diffusion. A problem at the Kennedy Center was to achieve a persuasive acoustical design compatible with the architectural concepts of Mr. Stone, that would perform the same function. In keeping with the period, Harris used no clouds or other modern devices.

Splayed wood panels, 3/8-in. thick and extending from ceiling to floor along the side walls are one such element of diffusion. Projecting about 30 in. from the wall surface, they provide ample diffusion at low frequencies. To facilitate diffusion at higher frequencies, Harris used a lapstrake construction in fabricating the splays whereby each vertical wood board overlaps the one adjacent to it so that varying widths are exposed. The panels are attached to a solid wall 6-in. thick with about a 1-in. airspace filled with a fiberglass blanket.

A solid plaster wall surface 3 ft., 11 in. wide separates each of the panels into which are set the side entrance doors to the hall, intentionally recessed 6 in. from the edges of the side wall splays to create additional diffusion.

Harris prefers his ceilings to be thoroughly broken up. The 52-ft. high ceiling of the Concert Hall is coffered and comprised of a multiplicity of hexagons about 1 ft. in depth. Set within them are stepped hexagonal surfaces of varying sizes centered around a small perforated metal hexagonal surface. Some are diffusers of the air-conditioning system, others are backed with solid plaster to prevent unnecessary acoustical absorption. Moreover, some 292 spherical balls intervene to further diffuse the sound and are interspersed throughout the ceiling for diffusion at high frequencies together with 11 large crystal chandeliers given by the government of Norway. Because of their unique tier design, the chandeliers diffuse the sound in several frequency ranges. To prevent bass frequencies from being soaked up, the ceiling is extremely heavy. A concrete plank above it insulates the Concert Hall from the kitchen and restaurant facilities overhead.

A very shallow balcony overhang obviates a reduction in sound level underneath it. A series of 1-in. thick plaster panels on metal lath comprise the balcony facias. Arranged in groups of three, they form splayed surfaces to contribute to sound diffusion.

The hardwood floor consists of red oak on the stage floor and white oak nailed on plywood in the seating areas.

Harris explained: "Wooden floors cost more, but you know how it is in a great hall. You can literally feel the music through your feet." Identical chairs are used in the three auditoriums, carefully scrutinized and chosen for their acoustical properties by Dr. Harris. A minimum of carpeting covers the aisles and crossover at the rear of the hall. In order to select carpeting which possessed the desired sound absorptive characteristics, Harris utilized an impedance tube measurement technique, choosing the carpet "on the basis of its sound absorption versus frequency characteristics, being lower than the other samples tested at high frequencies." After carrying out comprehensive comparative tests of various carpets in his laboratory, Harris chose a 70% wool, 30% nylon carpet with a cut pile of about 0.16 in. in height laid on concrete for all the theaters in contrast with the carpet in the exterior foyers where high sound absorption is a prime requisite.

The Concert Hall stage is surrounded by splayed surfaces similar to those on the side walls but varying slightly in dimension, thereby making it possible for the players onstage to better hear one another. The over 4,000 pipes of an Aeolian-Skinner organ dominate the upper rear of the stage but can be closed off from view.

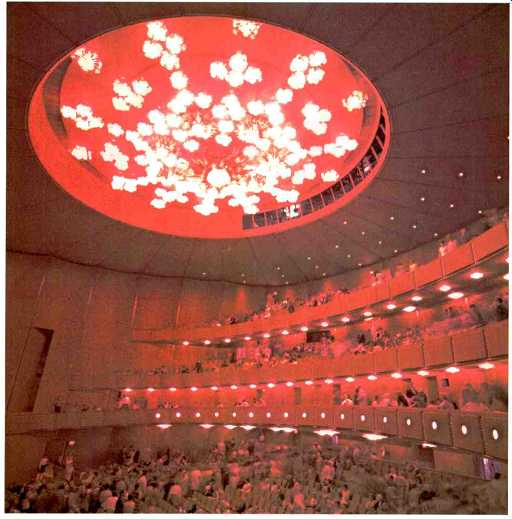

The Kennedy Center's borsch-red Opera House is the central theater and the most attractive of the three, playing host to musical comedy and ballet as well as to grand opera for which it was primarily intended. With a seating capacity of 2,319, the Opera House is in the shape of a horseshoe and it was the intention of architect Edward Durell Stone to achieve as much intimacy as possible for both performers and audience. This was accomplished. There is absolutely no bad seat in the entire house. Sightlines to one of the largest stages in the world-the space behind the curtain surpasses the auditorium itself-are uniformly excellent.

Adjoining convex-shaped cylindrical surfaces form the rear and side walls of the Opera House, separated one from the other by ornamental recesses. On the sides, these convex surfaces are constructed of 1-in. plaster on metal lath backed by 6-in. solid block which follows the convex shape. A 1-in. airspace lies between the plaster and the block. The rear walls are of a similar design but are constructed of preformed curved 3/4-in. wood paneling fixed to solid block. A fiberglass blanket is inserted into the intervening 1-in. airspace.

The center of the Opera House's ceiling is recessed and is of a 27-ft. radius broken up by 4 stepped surfaces tilted convexly downward. Mounted therein is a splendid starburst crystal chandelier given by the government of Austria which diffuses the sound at high frequencies. Convex diffusing surfaces radiate outward from the center of the ceiling, widening as they reach the outer edge. It is composed of plaster on metal lath and is of a minimum thickness of 1 in.

On the facias of the box tiers, curved panels bowed outward diffuse the sound waves and are formed of 3/4-in. plaster on metal lath. The floor, which slopes about 7 degrees, is fully covered with a low-pile carpeting laid on concrete.

Because the hall is to be used for speaking as well as singing, a lower reverberation time was required than for traditional grand opera.

The Eisenhower Theater for drama seats 1,142 persons and is the smallest of the three completed theaters. Contiguous triangular splays which extend from floor to ceiling form the rear and side walls and are made of 3/4-in. East Indian Laurel veneer panels mounted on 6-in. solid-block walls. Again fiberglass fills a 1-in. intervening airspace.

Each splay projects about 18 ins. into the theater and each side of the triangular splays is approximately nine feet in width.

A box tier and balcony have facias consisting of a series of vertical bars.

Lighting units for the stage lie behind the grill and behind these lighting units are fiberglass blankets. The soffits of the tiers are formed of 1-in. plaster on metal lath.

The ceiling is spanned by convex shaped surfaces from one wall to the other. It is resiliently hung from the slab overhead and is of I-in. plaster on metal lath. The floor, which slopes about 8 degrees, is fully carpeted with the same carpet that is used in the Concert Hall. It is interesting to note that in the 2h full theater Sargent Shriver fired a small cannon whose decay was recorded and analyzed by Dr. Harris two days before the official opening of the Eisenhower Theater.

I have attempted here to sketch out the tremendously detailed and complex acoustical plan Dr. Cyril Harris implemented in the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. In preparing this nontechnical blow-by-blow description, I am deeply grateful to the mastermind himself, Dr. Cyril Harris, who kindly permitted me to use his article "Acoustical Design of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts" which appeared in the Journal Of The Acoustical Society Of America, Vol. 51, Number 4 (Part 1) 1972. It is thoroughly informative and readable and is absolutely indispensable to this piece.

Readers who are interested in additional statistics such as reverberation time charts, tables, and architectural plans would enjoy reading his article in its entirety.

(source: Audio magazine, Nov. 1973)

Also see:

Engineering the Boston (Aug. 1990)

The Audio Interview: Avery Fisher--The Gift of Music (Sept. 1990)

============