Last month I reported on my visit to Decca Records in London and to the Decca cassette duplication facility in the village of Bridgenorth some 140 miles north of London. At the conclusion of my column, I described the listening test set-up by engineer John Baxter at the Bridgenorth plant, wherein one could switch between the stereo disc, the running master (from which the cassette is duplicated), and the production cassette of the same program. Now, on with the tests and the story.

Needless to say, levels between the three sources were precisely matched, as was synchronization of the signals from the playback machines. The disc was played with a Shure V-15 III phono cartridge into a Quad preamplifier. The running master and the production cassette were decoded through a Dolby 505 B Type unit. Quad amplifiers were used along with large Tannoy speakers.

On initial listening tests, switching between the three sources didn't reveal any readily apparent differences iii sound quality. Even with more extensive and detailed listening, it was obvious that the differences which were perceived, were fairly subtle. Of course, the occasional tick and pop of record noise was a give away that I was listening to a disc. Difference between the running master and the production cassette were well-nigh imperceptible-the former perhaps a shade cleaner, with a smidgin less noise. I think it is fair to say that the cassette is virtually a sonic mirror of the running master. Very careful comparison of the sound of the disc versus the cassette indicated there were some small variations in dynamic range, frequency response, and equalization. At this point I want to briefly discuss some aspects of disc cutting and tape processing.

I have noted that in Decca's case the stereo disc is made from the cutting master and is a second generation product. In the transfer from tape to disc, there are certain basic restrictions in disc cutting technology that must be considered. This is achieved by a complex juggling of the interrelated factors of low-frequency response, dynamic range, running time of the side, and the electromechanical characteristics of the cutter head.

Contrary to the propaganda about discs having a dynamic range of 70 dB (on lacquers, yes), under the best of circumstances a disc with a dynamic range of 55 dB is very good indeed.

More often than not, the actual dynamic range is appreciably less than this. Sad to say, but in the quest for high record levels many companies deliberately roll off bass response below 50-55 Hz. Those who conscientiously try to extend low frequency response down to 30 Hz are faced with side timing problems and coping with the energy and wide excursions of the cutting stylus at those low frequencies. Even with the aid of the automated controls for variable pitch and depth on the cutting lathe, dealing with all these variables is no mean feat. In spite of these problems and restrictions, the modern stereo disc is generally considered as the closest approach to the high fidelity of the original master tape.

Cassette Considerations

While the running master is made from the cutting master, since it is to be used for the production of cassettes, it is slightly modified to cope with certain problems of this medium, as well as to take advantage of other factors. For example, running time is not a concern, since on a tape there obviously can't be any inner groove distortion. With proper equalization, low-frequency response is easier to achieve on a tape. On the other hand, the narrow tape width and slow speed of the cassette limit its dynamic range and signal-to-noise ratio. Lack of headroom makes the tape prone to saturation with the subsequent easily discernible distortion. Thus, under "best case" conditions, the dynamic range on a cassette is held to about 40-45 dB. In order to stay within this range and to help avoid tape saturation, some mild compression is used.

I've gone into all this discussion, in explaining that in these A/B comparisons between the disc and the cassette, the cassette seemed with some program material to have a better balance and overall frequency response than the disc. In several instances, the bass response on the cassette was demonstrably superior to that on the disc. "Heresy," say you unbelievers? I'm just reporting on what I heard! Of course, these cassette productions were sonically "tailored" for this medium, but it shows that you can't just automatically assume that cassettes, even of this quality, are inferior to the stereo disc.

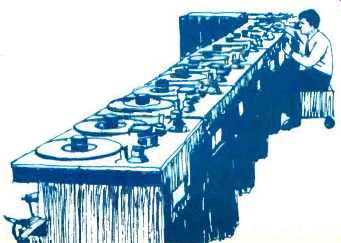

After the listening tests, we went into one of the old wards which was being used for cassette assembly. Local Bridgenorth girls were welding cassette halves, while others were using a machine which accepts the 14 in. recorded tape "pancakes" from the duplicating slaves and winds each program, complete with leader tape at each end, into the cassette shells.

Several girls were employed in taking random samples of cassettes and checking them with headphones for quality and to make certain that the proper program was being processed.

In still another section, labels were automatically affixed to the cassettes, after some girls had checked program against labels. Finally the cassettes were inserted into their cases, shrink-wrapped, and in various quantities put into shipping cartons. One special section handles London/Decca multiple cassette sets. These include operas and such items as the nine Beethoven Symphonies, the five Prokofiev Piano Concertos, etc. These are placed in cases which open like a book and can contain up to four cassettes plus applicable librettos or program notes.

It is deluxe packaging and evidently quite popular.

Before leaving Bridgenorth, I want to once again bring up the subject of modulation noise in cassette recordings. I think it is altogether remarkable how free the London/Decca cassettes are from this sonic plague. I have now listened to some 30-odd productions and have encountered just the slightest trace of it-for a brief period-in only three of the recordings. How have they managed to cope so successfully with this problem?

Modulation Noise

The main thing, of course, has to be the type and quality of the duplicating tape. I have just read an Ampex report on modulation noise in tape, and after much research into coating thickness, base thickness, solvents, binders, and methods of oxide milling, along with the viscosities of pigment dispersion...all of these turned out to be negligible factors. Among the things they did find significant is that magnetic orientation of the oxide particles with their long axis aligned in the direction of tape travel affords a 3-dB improvement in modulation noise.

Even more important is the calendering process and most specifically the type and construction of the calendering roller. Calendering tape produces a smoother finish to the oxide layer and a more even density of magnetic particles. The Ampex people found that irrespective of such aspects as heat and pressure, if the roller was a composite type-made up of layers of different materials-the non-uniformity in roller hardness caused oxide density variations. If the roller was homogenous, i.e. made of one type of material, calendering was uniform and improvements of as much as 12 dB in modulation noise were noted. Decca uses both BASF and Memorex tape. I remember from my visit several years ago to the BASF tape manufacturing plant in Wilstadt, Germany, that their tape was particle oriented while still in the wet stage on the coating base. I can't say what kind of calendering roller they used, but I suspect it was the homogenous type.

Memorex evidently used similar techniques. Thus, with the uniform density of the tape and Decca's proprietary method of ensuring a very tight head wrap on their duplicating slaves, they appear to have licked the curse of modulation noise in their cassettes.

Before getting back to London and my visit to the Decca recording studios, I want to give you the results of some tests of signal-to-noise ratios on the London/Decca cassettes which I conducted when I returned home.

Decca encodes all of their cassettes with Dolby B noise reduction, which in general should ensure low levels of tape hiss. But there are variables involved in the tapes, and people vary in their sensitivity to tape hiss. As a playback system I used a Yamaha TC800GL cassette deck feeding into a Mark Levinson LNP-2 pre-amp, a Lux man 4000 power amplifier, and a pair of Duntech DL-15 loudspeakers. I should add that I used the cassette deck's own integral Dolby B system, but also used a Dolby 505 B Type unit.

The Yamaha deck was selected not only for its excellent motion, but also because playback levels can be set on the meters, which happen to read down to-40 VU and up to +6 VU with a red LED indicator at +4 VU. Mr. Haddy had kindly given me a BASF DIN "Bezugsband" alignment cassette, (a very handy item that costs over $50) and my deck checked out within a few dB all the way from 31 Hz to 10 kHz. I used Dolby Labs level set cassette to line up playback on the Dolby 505 unit.

Hiss Levels

I played quite a number of the London/Decca cassettes to gain an overall impression of noise and then chose #SPC5-21148, which combines an excellent recording of the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto by pianist llana Vered with a stunning rendition of a piano transcription of Stravinsky's Petroushka, for test purposes.

Using a General Radio sound level meter, I placed myself 15 feet on axis between the loudspeakers and set playback levels so that the meter registered a peak of SPL of 88 dB on the "slow" C scale on the loudest fortissimo passages. At this level, there was a barely perceptible trace of tape hiss in the quietest pianissimo passages. With the masking effect of levels above pianissimo, there was no audible tape hiss. Some people would feel that 88 dB SPL at 15 feet is quite loud, but such is the dynamic range on the cassette that the pianissimo sections are really quite low level. For better dynamic range and a heightened sense of realism, I increased the level to peak at 96 dB SPL. At this level, there is a tape hiss evident in the pianissimos but certainly not an objectionable amount, and here again the masking effect of higher levels helps out immediately. Those equipped with the Phase Linear auto-correlator will find that it removes the thin veneer of hiss very nicely. In fact, this is when the auto-correlator is at its best...removing small amounts of hiss from material which isn't grossly "hissy" to begin with. For those not so equipped, at the Decca studios I saw and heard a "black box" proprietary single-pass noise reduction system, which worked quite effectively with no audible degradation of sound. This is to be used with older tapes, including Dolby, and perhaps even with new recordings. As with other record companies who Dolbyize their cassettes some of the old productions were made at a time when tape oxides and tape machine S/N ratios weren't as quiet as they are today. Used with new recordings, this "black box" should ensure really quiet recordings.

I should point out that the perception of tape hiss can be heightened by the mid- and high-frequency peaks in a room, and needless to say, many speakers have response peaks which exaggerate tape hiss. With the Dolby 505 tracking on the nose, and my very flat playback system, even when ambient levels in my listening room reach below 40 dB about one o' clock in the morning, on average, tape hiss is not obtrusive. Summing up my overall attitude towards these new London/Decca cassettes, I'm bound to say they make a very strong challenge to the stereo disc. Most of the recordings are quite good, with a number of outstanding productions like the complete Porgy and Bess, a Madame Butterfly which is really top drawer, Scheherazade and An Alpine Symphony with Mehta and the LAP, Also Sprach Zarathustra with Solti and the Chicago Symphony, G and S Trial by Jury. ..a real winner here...and the late Bernard Herrmann conducting Great British Film Music. It is early on in the game yet, with not many titles available; but thus far, the cassette processing has been really excellent and more important...consistent.

Old "Crooner" Returns

When we arrived at the Decca recording studios in London, Bing Crosby had just finished his first recording session in England in 14 years. Seems Bing is a very good friend of Sir Edward Lewis, chairman of the board of Decca Records, and this was a very special recording with Arthur Haddy himself in charge of the sessions. Bing is now 75, and, as you probably know, his recent operation left him with one lung. It was most astonishing to hear a playback of the recording, with Bing producing those deep sonorous chest tones as in the days of yore! Bing's session was held in the main studio, and that was my first surprise. It is a very large high-ceilinged room, big enough to hold a modest-size orchestra of sixty-odd men, and, by Gad, it is a live room with a reverb period of about 1 to 1.2 seconds! No ultra-dead studio acoustics here. Naturally, the room was replete with absorptive and reflective goboes, isolation booths, etc. The control room has a multi input/ output console built by Decca, an 8-track Scully, and a 16-track 3M tape machine, along with the usual 2 and 4 trackers. Microphones were in mad profusion in the studio, with the usual assortment of Neumanns, etc. There are several other studios, this time of the traditional "dry/dead" variety with EMT reverb plates, and more multi-track recorders. There are also many rooms devoted to tape editing, dubbing, and preparation of running masters for the cassette operation.

Tape machines in evidence were by Studer, Philips, and Scully. No Ampex units, but everywhere was the familiar rainbow label of Ampex 406 tape which they use by the mile. The one in. running master for the cassette duplication is prepared on Ampex Grand Master tape. The disc-cutting rooms had the usual Neumann lathes, but the cutting amplifiers were special units of Decca's own design with the ability to cope with phase problems.

One room, a sort of test lab, was presided over by Cyril Windebanke, resident of "Golden Ear" and a fascinating repository of recording tales. Cyril personally likes quadraphonic sound, but "officially" Decca is still uncommitted. As you know, Decca records are all over the world, including the U.S. When their engineers go out on those remote symphony sessions, I understand a two channel master is recorded on a Studer A80, and an 8-track, one-inch master is simultaneously recorded...just in case someday they might need such an item.

Disc Differences

Now to something which I know is going to kick up a storm of controversy. There is a highly vocal band of audiophiles and music lovers in this country who regularly shell out several extra dollars to buy imported discs from Decca, rather than the equivalent music on London Records, the Decca branch in the U.S. They do this because they are firmly convinced that the Decca pressing is of far better quality in sound and has superior physical qualities to those obtainable on London Records. I had a long conversation with Arthur Haddy about this, and he vehemently states that there is absolutely not one iota of truth in this notion. There was a rumor going around the U.S., that even if the Decca and London discs were made from the same stamper, the U.S. got discs from the "tail end" of the stampers life. Mr. Haddy states that, in fact, often the reverse is true...with London Records getting the first run from the stamper. The only difference between Decca and London records is that the Decca cover is of a lighter cardboard stock, and the cover picture is not the same as the U.S. version. Otherwise, everything is positively and incontrovertibly the same.

To conclude this story, while in London Ruth and I had the pleasure of a lovely visit with my friend Leopold Stokowski. At 94, this amazing man is a bit frail and moves a bit deliberately, but he is still very active and alert. The day before we saw him, he was recording for Columbia. We discussed the musical scene and repertoire, and I recalled the recordings we made together. He said, "Bert, that was the past...what are we going to do in the future?" Bless him! Believe it or not, he has just signed a six-year contract with Columbia with the last sessions to be held two weeks before his 100th birthday! I guess that kind of attitude is how you get to be 94. May he continue to flourish.

( Audio magazine; Nov. 1976; Bert Whyte)

= = = =