OUT ON A LAMBDA

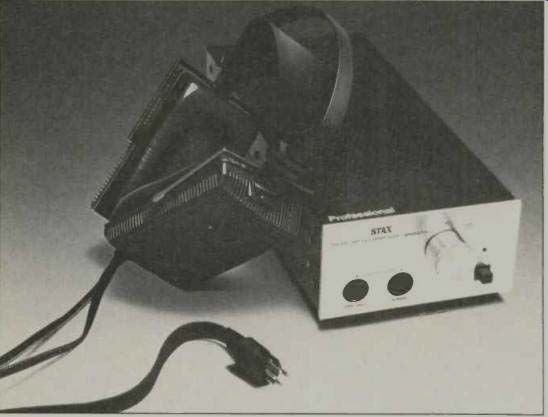

above: Stax Lambda Professional

Thirty-three years ago, I was a sales executive and music director of Magnecord, the Chicago-based company which, along with Ampex, pioneered the development and manufacture of professional magnetic tape recorders.

By 1950, the Magnecord PT-6, a 71 or 15 ips, quarter-inch full-track recorder, was well-established as the workhorse of the broadcast industry.

Needless to say, this was a monophonic machine, but the winds of change were already blowing even in those early days. We received a request from the U.S. Navy Special Devices Center in Sands Point, New York for a Magnecorder that could record two channels of data from underwater sonar experiments. Almost at the same time, there was a request from General Motors for a two-channel recorder for the study of interior noise in their cars.

There was no such thing as a stacked two-channel magnetic head in those days, so Magnecord took an expedient step. They used two half-track heads, with their magnetic gaps separated by 1 1/4 inches, thus achieving the necessary track isolation for the two independent recording channels.

Having made several of these two channel Magnecorders with what came to be known as staggered heads, we recalled the binaural hearing experiment with "Oscar, the dummy," a popular feature at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair. This showed how the time of arrival and intensity of sound give us our directional cues in the normal hearing process.

All this led to our first experiments in the binaural recording of music, using two microphones spaced 6 to 8 inches apart. We would record in this mode or with a baffle board between the microphones to simulate the human head's shadow.

Binaural recordings were played back via headphones. In those days, we didn't have the wide choice of high quality headphones we have now. In fact, the best headphones we could come up with, made by a company called Permoflux, actually had been made for military pilots during World War II. They were heavy and clumsy, and still had those bright yellow chamois ear pads. Wearing them, you felt like you were heading out on a bombing mission! As you can appreciate, frequency response wasn't the greatest, with response dropping like a stone at about 7 to 8 kHz. Nevertheless, the Permoflux phones served well to introduce many people to binaural recording. Few ever forget the incredible thrill of listening to true binaurally recorded music for the first time.

I was soon very involved with making binaural recordings and would go anywhere and do almost anything to record binaural music. I recall bootlegging the U.S. Navy Band through a pair of mikes surreptitiously lowered from a crawl space above the ceiling of a high school auditorium in suburban Chicago! On another occasion, I recorded Woody Herman and his Thundering Herd at the Blue Note nightclub in Chicago. The day after the recording was St. Patrick's Day, and I invited Woody and 14 of his band members to a friend's house for dinner and to listen to what we had recorded.

I cooked up a huge vat of corned beef and cabbage, and we had copious quantities of Guinness stout on hand.

At Magnecord we had made up some multi-output jack boxes so that several sets of headphones could be used simultaneously. I had brought enough multi-jack boxes for 16 sets of phones, and after we were all well-fed with the corned beef and well-lubricated with the Guinness, we started our listening session. You can imagine what a sight this was--all of us sitting in a circle on the floor of the living room, each wearing the Permoflux headphones with the bright yellow ear pads, the tangle of connecting cords to the jack boxes, and the binaural Magnecorder in the center. Of course, there was no sound of music in the room, but everyone was swaying and gyrating, and shouting comments to each other about their performance the previous night. To a stranger walking into the room, it would have looked like some strange tribal ritual.

I still have those Woody Herman binaural tapes, as well as similar recordings I made in the Blue Note with Stan Kenton and Benny Goodman. After more than 30 years, without any special care in storage, the tapes are still in good condition, with only a slight amount of "cupping"--a longitudinal curvature-due to the gradual drying of the plasticizer in the tape.

Magnecord also produced a standard PT-6 BN binaural recorder, and many of my recordings were demonstrated at the Audio Fairs of that time. I received a request for, and supplied a binaural Magnecorder to, one Edward Tatnall Canby of Audio Engineering magazine, who duly reported on his experiments with this recorder.

I soon moved on to stereo, and in 1951 made my first such recording with Leopold Stokowski, Monteverdi's Vesper Mass of 1610. I also had the pleasure of working with the late Bob Fine. He was making his superb monophonic Olympian Series recordings for Mercury with the Chicago, Detroit and Minneapolis Symphony Orchestras, while I was experimentally recording them in stereo.

All of the foregoing is a preface to the main thrust of this column-to wit, how far technology has advanced headphone design from those primitive Permoflux phones to the sophisticated, high-quality headphones of today. In this digital era, the headphone is finding an increasingly important role, and it is obvious that listening to music through headphones is a very widespread practice these days. I don't mean just the Walkman phenomenon, though that too seems to be spreading, but rather listening through good-quality headphones to a home stereo system. There are innumerable people living in apartments who simply cannot play their loudspeakers at high levels for fear of bringing down the wrath of neighbors. Others wish to retreat into private musical worlds and escape the nonstop TV of their kiddies.

It is also generally acknowledged that, despite the many very high-quality dynamic headphones on the market, electrostatic headphones offer the highest fidelity of reproduction.

One of the companies preeminent in electrostatic headphone design is Stax Kogyo of Japan. Their various models have generally found a good deal of favor among audiophiles, but one which is particularly well regarded is the Stax Lambda headphones-or "earspeakers" as Stax calls them.

The Stax Lambda's large, elliptical diaphragm entirely covers the ear. It is ultra-thin, only 2 microns thick, and is made of a high-polymer film. This almost massless diaphragm permits near-instantaneous acceleration, so transient response is lightning fast. The diaphragm is said to be essentially free of internal resonances, and thus tonal colorations are absent. Frequency response is claimed to be a phenomenal 8 Hz to 35 kHz, and the maximum output is said to be 100 dB SPL! I can testify that the dynamic range is extremely wide, and the sound quality is outstanding, utterly clean, transparent, and oh so effortlessly produced. These phones are tonally accurate to an incredible degree and can ruthlessly expose the shortcomings of any type of program material.

The SR Lambda earspeaker is optimally driven by the SRM-1/MK2 Class A amplifier, which provides 210 volts in a direct-drive configuration, thus eliminating the need for coloration-producing coupling transformers. The SR Lambda earspeakers and the SRM-1/ MK2 are a formidable combination and have enjoyed a reputation as the most critical monitoring system extant.

This is a view also held by none other than Daimler-Benz, the German manufacturer of the prestigious Mercedes automobiles. Now history repeats itself: Just as General Motors was studying car interior noises 33 years ago, Daimler-Benz is conducting similar research today. This time around, the research is an even more highly sophisticated effort. It appears that most car noise presently lies in a very low frequency range, and is produced at very high levels. The extended low-frequency response of the Stax Lambda earspeakers (8 Hz) was just what the Daimler-Benz engineers needed, but there was not sufficient output from the phones.

The car maker thus asked Stax to make a special Lambda earspeaker that would satisfy their requirements, and Stax responded with the Lambda Professional System. To produce low frequencies at higher output levels, the phones needed a larger spacing between the electrostatic elements and the electrodes on either side, to permit greater excursions of the element. The electrode gap was thus changed from the 0.3 mm of the standard Lambda to 0.5 mm on the new Lambda Professional. However, this wider spacing of the electrostatic element caused a weaker electrostatic field, necessitating a redesign of the direct-drive amplifier. Voltage was increased more than 2 1/2 times-to 580 volts. The greater excursion of the diaphragm and the higher voltage drive enabled Daimler-Benz to get their desired high output bass response.

Stax decided to make the Lambda Professional System available to audiophiles, pricing it at $780. The lightweight units weigh only 325 grams and they are equipped with a connecting cord with a specially polarized plug.

The SRM-1/MK2 Professional Class-A direct-drive amplifier has a polarized receptacle for one pair of Lambda Professional earspeakers and another for a pair of the standard Lambdas. A volume/balance control is on the front panel of the amplifier, which measures 150 mm W x 87 mm H x 370 mm D. Other side benefits resulted from the work on the Lambda Professional. The already very low distortion was reduced a further 10%, while maximum SPL increased 5 dB and sensitivity 2 dB. I have been using a Lambda Professional System for some months now, and it is truly incredible, really quite extraordinary. If' only a loudspeaker could sound as clean, detailed, transparent and open, and distortionless as these earspeakers, we would be in hi-fi heaven! If you want to find out how everything really sounds in your system up to the point of amplifier output, listen via the Lambda Professional System and all will be starkly revealed.

If you want the ultimate in sound quality, just hook up the output of a CD player to the input on the rear of the SRM-1/MK2 Professional amplifier, put on the Lambda Professional ear speakers, and play a well-recorded CD. The result can be magical-an incredibly detailed sound with absolute tonal purity, ultra-wide frequency response and dynamic range, and without a trace of noise! This Lambda Professional System is so exacting, so critical a monitor, that it is ideal for auditioning CDs. Believe me, if it sounds poor on the earspeakers, with even the slightest stridency on high strings, it will sound awful through your loudspeakers. It's a truly great sound-but there are several caveats.

Just remember the Compact Discs (those that are not compressed) and the Lambda Professional System are capable of more than 90 dB dynamic range. One must be absolutely certain the volume control is turned way down before commencing to listen-each of us has only one pair of ears. It also must be noted that all of the music heard through headphones has been recorded for playback through loudspeakers. Thus, when listening through headphones, the effect can be quite pleasing and even spectacular, but in truth it is a distortion of perspective.

What is needed is a return to true binaural recordings, ones made specially for headphone listening. It would not be that expensive to run a parallel digital recorder to accept binaural sounds, and there is a huge headphone market to justify the release of such recordings.

Digital binaural! Wow!

-----------

(Source: Audio magazine, Nov. 1983; Bert Whyte )

Also see:

Stax Electrostatic Earspeakers (ad, Aug. 1984)

Stax SRX-II Electrostatic Earspeaker system (ad, April 1975)

= = = =