by Dr. Robert F. Weirauch

(Note: Due to damaged/missing pages from original article, some content is missing, as denoted by "[...]")

TO MANY PEOPLE, a full symphonic score represents a compendium of Etruscan hieroglyphics. Moreover, if someone were to sit down at the piano and reduce this super-secret code to meaningful sounds, then surely that individual must be possessed by the devil (if not by the spirit of Franz Liszt). While there is much intricacy and study involved in reading a score, nevertheless, anyone can read the basic "do-re-mi's" should be able to derive a good deal of understanding and musical comprehension with just a little effort. Even if one cannot read a single note of music, a certain amount of understanding and recognition can be obtained by being able to differentiate between the musical elements-melody, harmony, and rhythm-and by following the graphical rise and fall of a given musical line (as many chorus singers, who learn their parts by rote, are forced to do). By connecting the visual notes with the aural impression, especially when clever compositional techniques are not so easily grasped by the ear alone, the appreciation of a given work is heightened tremendously.

Many good conductors consider it sine qua non to be able to play a score at the keyboard (even; if necessary, at first sight). Surprisingly enough, on the other hand, quite a few composers are their own worst orchestrators, requiring others to correct or actually transcribe their scores for them. But conductor, composer, and the millions of music lovers who enjoy their combined recorded (or concertized) efforts can all share in this creative manuscript, without the need for advanced degrees in musicology, electronics, and/or computer programming (toward which goals the audiophilic art appears headed). Opera houses all over the world reserve special rows of seats in their balcony with tiny lights for those patrons who bring their own scores with them to performances. The purpose of this article, however, will be to encourage consultation of a score before and after a hearing, at a time when one can leisurely make intelligent use of the principles to be enumerated.

A score is simply the combined listing of all instrumental (and vocal) parts in a manner (parallel, one above the other) such that at any given moment the note (or rest) assigned to any given performer can be viewed with all others in a single, vertical column. The music as a whole is then read in normal fashion (i.e. from left to right), taking in up to an entire page at a time. This is what terrifies the uninitiated . . . having to read as many as two dozen horizontal lines all at once. The secret, of course, is that one need not read each individual part simultaneously, but, recognizing duplication and similarity, condense them into three or four basic parts. Usually only one or two chords at a time are studied in such detail that everyone's contribution to it is methodically analyzed. Before delving into this esoteric art, however, let us limit somewhat the boundaries of our investigation.

We will only consider symphony orchestra scores, since the vast bulk of instrumental music was written (and recorded) for this particular ensemble.

This means we will not consider bands (military, symphonic, jazz, or studio), since they each have their own unique instrumentation-all differing from that of the symphony orchestra-and are deserving of a special investigation in their own right. Moreover, we will not consider the orchestra prior to the first quarter of the 19th century (the so-called Romantic Period), since instrumentation was undergoing a rapid development from the Renaissance, Baroque, and into the early Classical Period. Our principles, however, can easily be applied to orchestras before 1825, insofar as the orchestra is basically a nucleus of stringed instruments complemented by varying numbers of woodwind, brass, and percussion instruments.

As an interesting historical observation, it should be pointed out that the ratio of woodwinds and brass to strings has more or less progressively increased through the years. In the Haydn and Mozart orchestras of the 1770's, there were added to the 30 or so string players anywhere from two oboes and two French horns to pairs of flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns, and trumpets-clarinets were only used in two of Haydn's 104 symphonies and five of Mozart's 41-thus, providing a ratio of up to one to four. With Beethoven, who added two more horns and three trombones, the classical orchestra ratio was approaching one to three. Brahms, Bruckner, Tchaikovsky, and other Romantic composers then added at least two more horns, a piccolo, English horn, bass clarinet, contra-bassoon, tuba plus various percussion instruments. All the while the numbers of stringed players was also increasing, as witnessed by Berlioz--whole volumes have been written on what this genius did to and for the orchestra-calling for at least 15, 15, 10, 12, and 9, respectively, for the first and second violins, violas, cellos, and basses. With Wagner, Mahler, and Richard Strauss, woodwinds were sometimes increased from three's to four's, horns doubled to eight or more, and trumpets similarly augmented, although four trombones seemed to satisfy the most demanding. As if that were not enough, Wagner invented a quartet of tubas. Thus, in some late Romantic and early Modern works, the ratio of winds, brass and percussion to strings approaches one to two.

Our investigation, then, will limit itself to what is customarily called the modern symphony orchestra: winds basically in threes, at least four French horns, two or three trumpets (although the French and Russian composers favor a pair of trumpets plus another pair of the softer sounding cornets), three trombones plus tuba, a battery of percussion instruments (including harp and piano), and the string body.

With the increased string players, a large orchestra of about 96 players will again be in the one-to-three ratio. A good orchestra will cut down its string players for early classical works and will bring in extra performers if needed in modem selections.' Our included score samples will not contain works representative of the ultra-modern school (Stockhausen, Berio, Boulez, Cerha, Cage, et al.) and that called "alleatory"--which means the actual performance is left up to chance permutations of the musical elements and is usually never played the same way twice (indeed, it often cannot be)-since the score becomes a mathematical plan of symbols and instructions with charts, graphs, and sliding rulers. For the same reason, we will not consider electronic music, but will choose several interesting symphonic works (in which specific notes were written to be performed in unalterably specific ways) from Berlioz (1830) to Prokofiev (1944). The order of instruments in a symphonic score reading from top to bottom pretty well adheres to the following scheme: piccolo (also doubling as 3rd flute), two flutes, two oboes, English horn (technically neither a horn or English in origin, but in reality an alto oboe-also doubling as 3rd oboe), two clarinets and a bass clarinet, two bassoons and a contra bassoon, four French horns, two or three trumpets (or two trumpets and two cornets), three trombones (usually two tenor and one bass-in Beethoven's time there was the higher alto trombone, but a good tenor trombonist today can achieve the same upper register), timpani (two or more drums played' by one or more percussionists), snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, etc., harp and piano, and the usual five-part strings.

Fig. 1-Treble, bass, alto, and tenor clefs, each showing "middle C."

Fig. 2-Berlioz' Symphony Fantastique, Opud 14, page 23, Edwin Kalmus Publishers,

New York, (No. 144).

['Notice the trend toward performing Barogue works (such an Handel's Messiah) with reduced instrumental forces, on antique musical instruments and using the original manuscripts. In German, B-flat is translated o'B, " while B natural becomes "H." ]

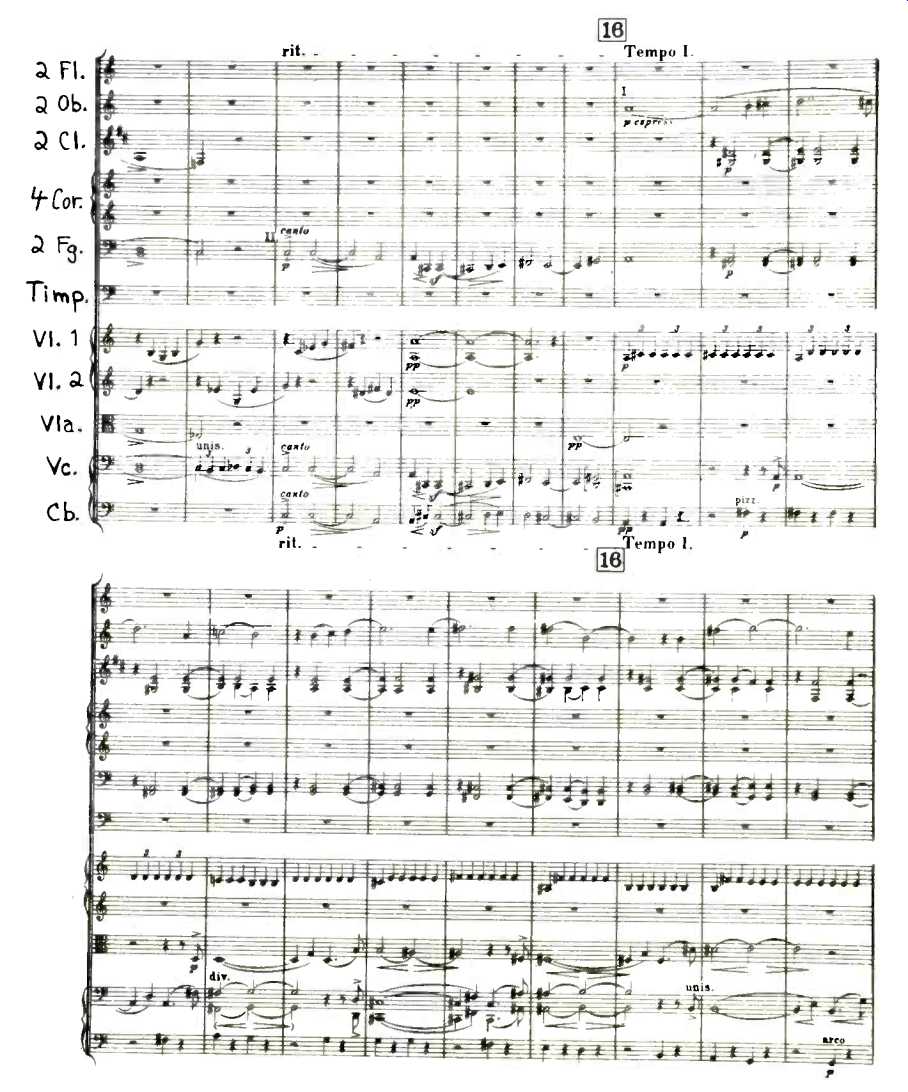

Fig. 4--Bruckner's Symphony No. 9, page 181 , Ernst Eulenberg, Ltd., London,

(No 467).

Before looking at the music there are two problems to be overcome. One is the fact that the different instruments will be listed in either French, German, or Italian, depending on the nationality of the composer or publisher. Most names are easily recognizable, but a few can cause some confusion. For example, "cor anglais" means English horn (and therein lies the misnomer--"anglais" is incorrectly derived from the word meaning "angled," referring to the shape of the tube), "corno" means French horn and not cornet, "tambur" means drum and not tambourine, "timbales" (three syllables) are kettle drums and not cymbals, etc.

When abbreviations are used the confusion becomes even worse.' The only solution is to obtain a small pocket dictionary of musical terms, which will also be invaluable with respect to the annotations given to the performers and conductor by the composer.

A more serious problem concerning score reading deals with the fact that some instruments are in concert pitch, while others are transposing. This means that when all instruments play […]

German, and the only abbreviations which might cause any difficulty are Hb. (Hautbois for oboe) and Br. (Bratsche for viola). This is a very celebrated example in that it shows three main themes playing simultaneously, with no other harmonic or rhythmic background. Theme one (that of the mastersingers, which opens the overture) is found in the bassoons, bass tuba, and contrabass. Theme two (the mastersinger guild, which occurs early in the beginning, only twice as slowly) is played by flutes, oboes, second clarinet; second, third, and fourth horns, and trumpets. Theme three (Walter's Prize song) can be found in the first clarinet, first horn, first violins, and cello. As with the previous example by Berlioz (whose music had more of an influence on Wagner than he cared to admit), there is an interesting canonic counterpoint in the second violins and violas (measures two and three).

The third example is from the final movement of Bruckner's Ninth Symphony. At this particular point the instrumentation finds flutes, oboes, and clarinets in three's, four horns, two trumpets, two trombones, and strings. The principal melody is in the trumpet part (doubled) with a basic contrapuntal "walking" bass line in the violas, cellos, and contrabasses. The harmonic background is provided by the first and second violins, who spell out the chords in slow arpeggios, plus the third and fourth horns and two trombones playing the exact rhythm of the trumpets. Now take a closer look at the woodwinds. The second and third oboes are playing the mirror inversion of the melody in the trumpets. The flutes, clarinets, and first oboe are then playing a canonic answer to the trumpets one measure later. Finally, in the third measure the first and second horns play a cononic answer too, and one half measure after, the mirror inversion! Even with a score all these lines are not easily followed, but it helps.

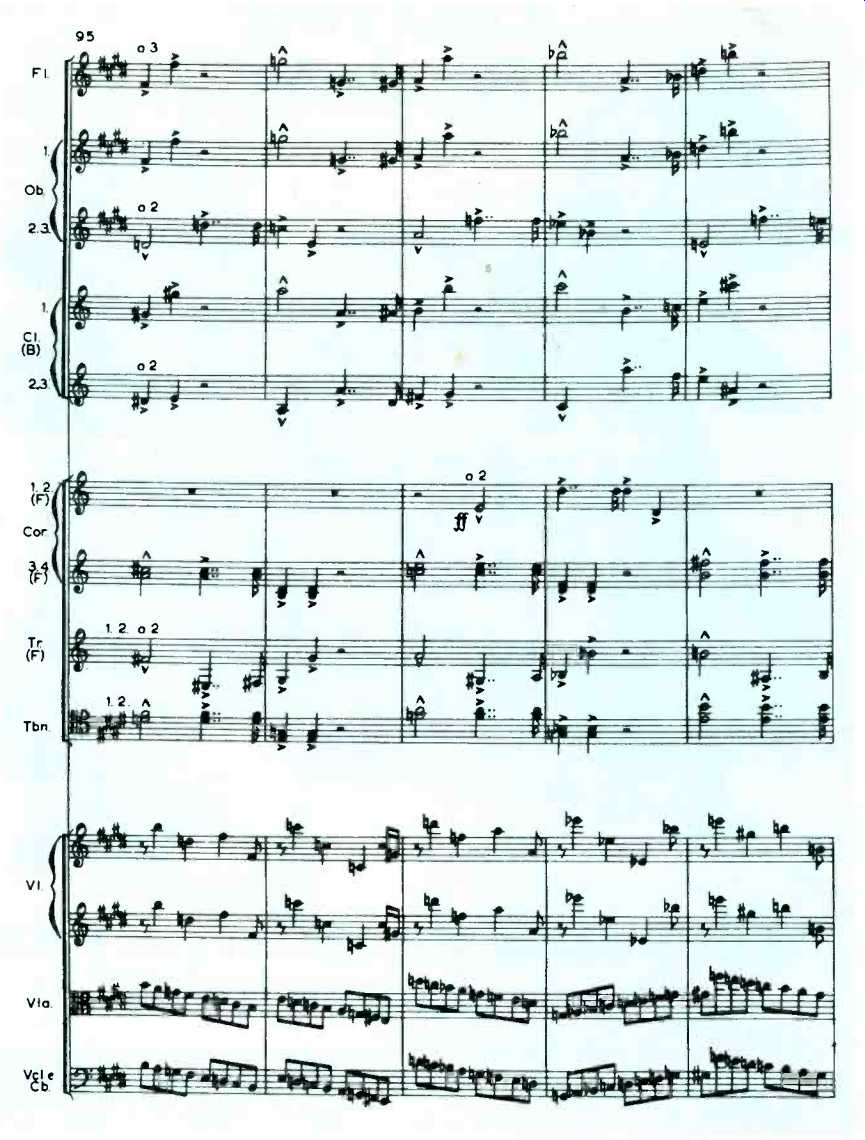

For the last example, let us take a page from the final movement of Prokofiev's Fifth Symphony. The instrumentation here is piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, a piccolo clarinet (pitched higher than the standard one), two B-flat clarinets, two bassoons, three trumpets, four horns) the Russians like to reverse these two groups), three trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, wood block, snare drum (tambur militaire), piano, harp, and strings. The first interesting thing to note about this score is that all instruments are in concert pitch--they sound the notes you actually see, although they may play different written notes. Even though this score can be considered quite modern, it is basically simple to read and analyze. The melody is found in the first trumpet, three trombones, and violins, violas, and cellos (with the tuba and contrabass adding individual notes occasionally). The harmony is given by repeated eighth notes in the horns, second and third trumpets, and bassoons. The remaining woodwinds are divided into two different rhythmical figures outlining the harmony, and the various percussion instruments (including piano and harp) accentuate these figures.

As a serendipitous reward to our score study, consider that rhythmical figure played by the piccolo, flutes, and piccolo clarinet. Since they are in unison and octaves, it doesn't require too much musicological expertise to discover the printed mistake in the first measure of the piccolo clarinet (the circled "g" should be an "a"). This calls to mind the humorous story concerning a new guest conductor so desirous of making a good impression with a prestigious symphony orchestra that he penciled a mistake in one of the obscure back-row instruments.

During rehearsal the next day the conductor suddenly stopped the orchestra and said, "Excuse me, second bassoon, [...]

(adapted from: Audio magazine, Dec. 1972)

Also see:

Remasters of Living Stereo (Aug. 1993)

============