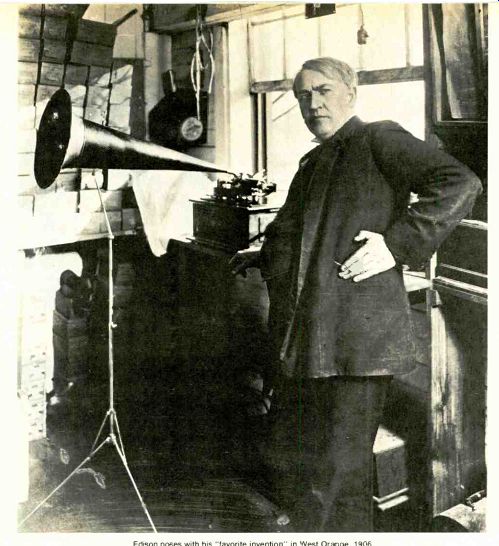

above: Edison poses with his "favorite invention" in

West Orange, 1906.

by Robert Long

An informal picture history culled from the files of, and photographed at the Edison National Historic Site in West Orange, New Jersey.

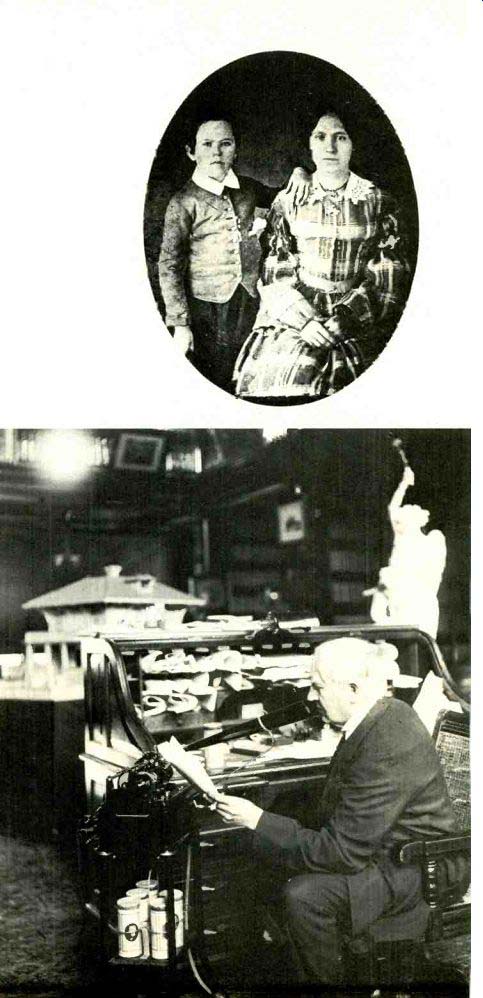

------- Perhaps the most attractive surviving picture from Edison's

childhood is this photograph of -Al" (for Alva) and his sister "Tanie" (Harriet

Ann) from the mid-1850s, when he was seven or eight and she was about

twenty-one. His deafness would begin some five years later. By 1B62,

at fifteen, he was publishing his own newspaper.

Later that year, when he heroically saved a stationmaster's son from certain death under the wheels of a boxcar, the grateful lather began teaching him telegraphy--his first technical training of any sort and the foundation of his earliest triumphs as an inventor.

By 1911, when this photograph was made in Edison's West Orange office -library, he was the grand old man of invention. (Note the atypically natty attire.) His dictation machine is, of course, an Edison phonograph; this application of the wax cylinder was important to its formative years, though Edison did not resist musical applications, as legend has suggested.

Two other inventions represented in the photograph are the light bulb (the bamboo -filament bulb still is used today in the statuary fixture at the upper right) and the concrete house, a model of which is visible behind the desk.

----------

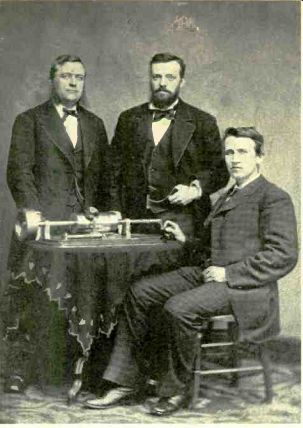

This photograph was taken April 18, 1878, on the occasion of Edison's demonstration of the phonograph for President Rutherford B. Hayes, members of Congress, and the National Academy of Sciences. With the inventor and the so-called "demonstration phonograph" are Uriah Painter, his liaison man in Washington, and Charles Batchelor, his associate, who as co -inventor received a percentage of all Edison's royalties. Edison's Washington sales agency later became the most successful in selling dictation equipment, mainly to government agencies; today's Columbia Records can trace its lineage to this company (via the Columbia Phonograph Company. Levin Handy of the Matthew Brady studio in Washington took the photograph; a more familiar version shows Edison alone with the same phonograph, but a different backdrop.

------------

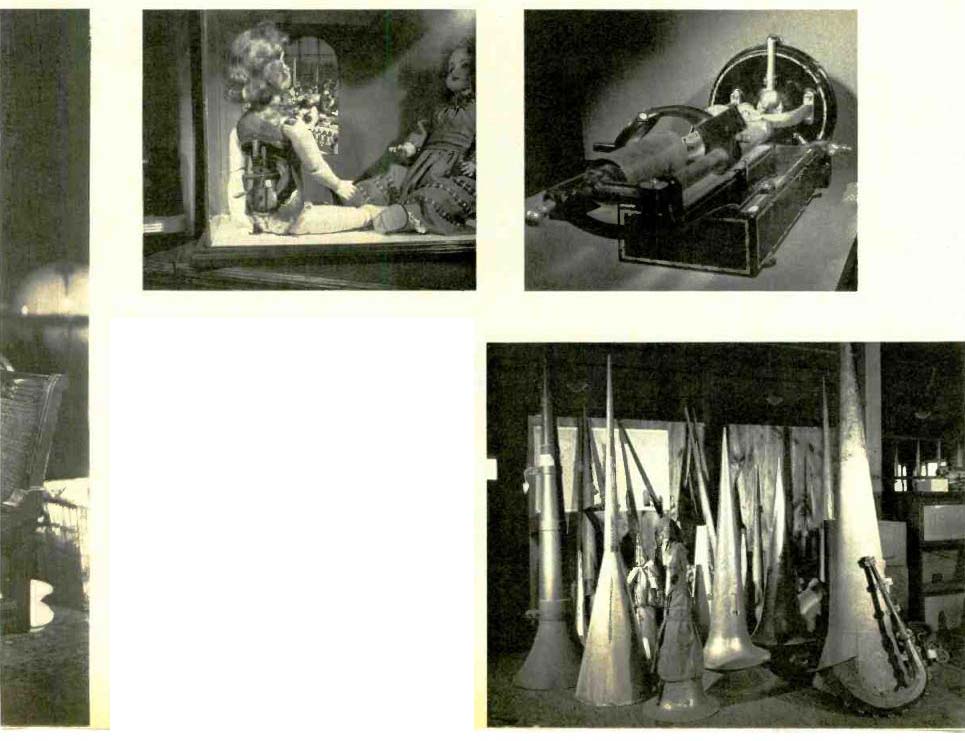

Talking dolls were the first consumer products to embody Edison's phonograph--and, later, Emile Berliner's flat-disc gramophone. The Edison doll, shown in its display case at the National Historic Site, used a hand crank as motive power. (Note the photo of the doll assembly line in the background.) Motive power for the phonograph at upper right was its water wheel at the far end, which was driven from a tap via a hose This is the type of unit sent by Edison to pianist Josef Hofmann in 1890, referred to in "Notes to Future Scholars" at the end of "Recordings Before Edison" in this issue.

The variety of recording and reproducing horns that Edison experimented with is almost endless-one recording horn measured 125 feet.

Those at right are only part of the West Orange Historic Site collection.

---------------

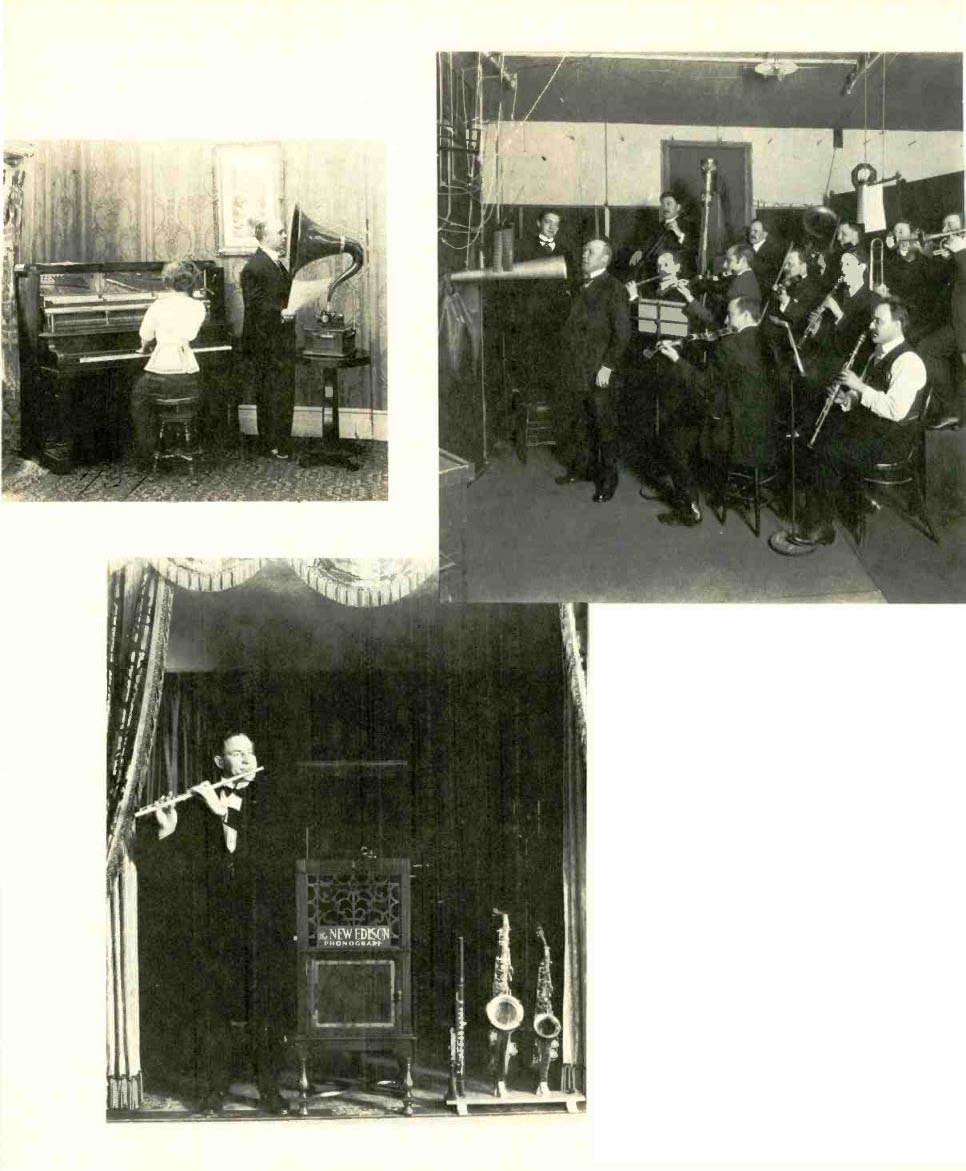

The publicity photo at the upper left, in which a cobra-like recording horn seems about to swallow the musical master of the house, dates from the early years of this century, when the disc gramophone was rapidly growing n popularity. While Edison's cylinder machine could be used to make home recordings, the gramophones couldn't, and this picture is intended to dramatize the fact. Note that the front of the piano case has been removed to improve the sound pickup. By 1916, when Jacques Urlus (above) was photographed as he recorded in Edison's New York studios at 79 Fifth Avenue (pint-size conductor Cesare Sodero is standing on a stool), a harp could be placed at some distance from the recording horn and string players could use standard instruments instead of the Stroh horn -equipped designs that sacrificed tone quality to volume. This session presumably produced both cylinders and the recently introduced Edison Diamond Discs. Tone Test recitals such as that given by instrumentalist Harold Lyman (left) at Atlantic City in 1924 demonstrated with apparent success-see " Edison as Record Producer" in this issue-that the Edison disc could not be distinguished from the live performance.

------------------

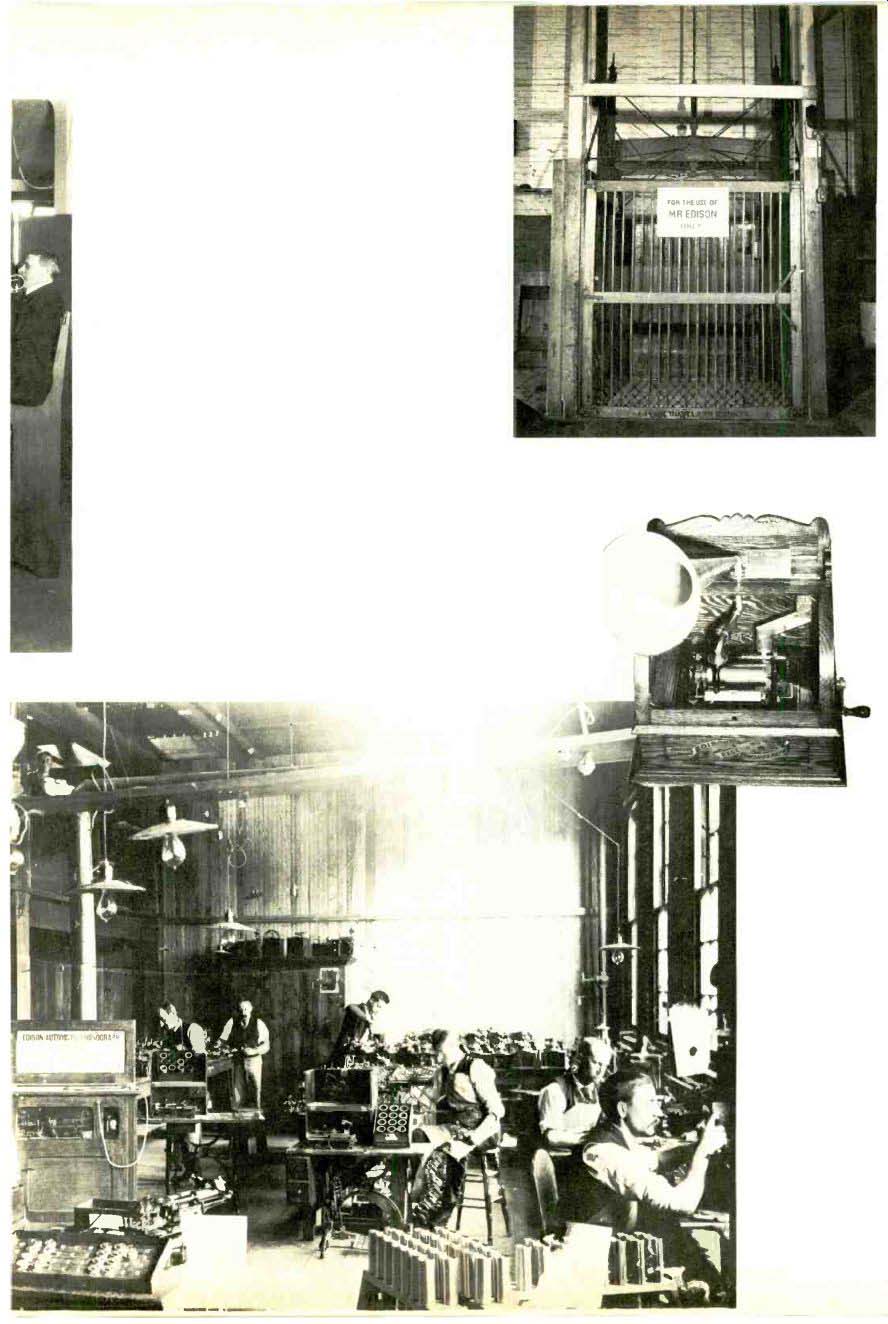

Edison's presence is everywhere in the lab at the West Orange National Historic Site, but nowhere more than in this elevator, still reserved for him.

Despite the inherent recordability of Edison's cylinders, those already recorded with musical selections early became important to the commercial success of the phonograph. The coin -slot model to the right is generally regarded as the first jukebox; it demanded both a nickel and motive power (note the hand crank) of its customers. By 1890 the jukebox -assembly operation in the West Orange plant had assumed the proportions documented below.

-----------------

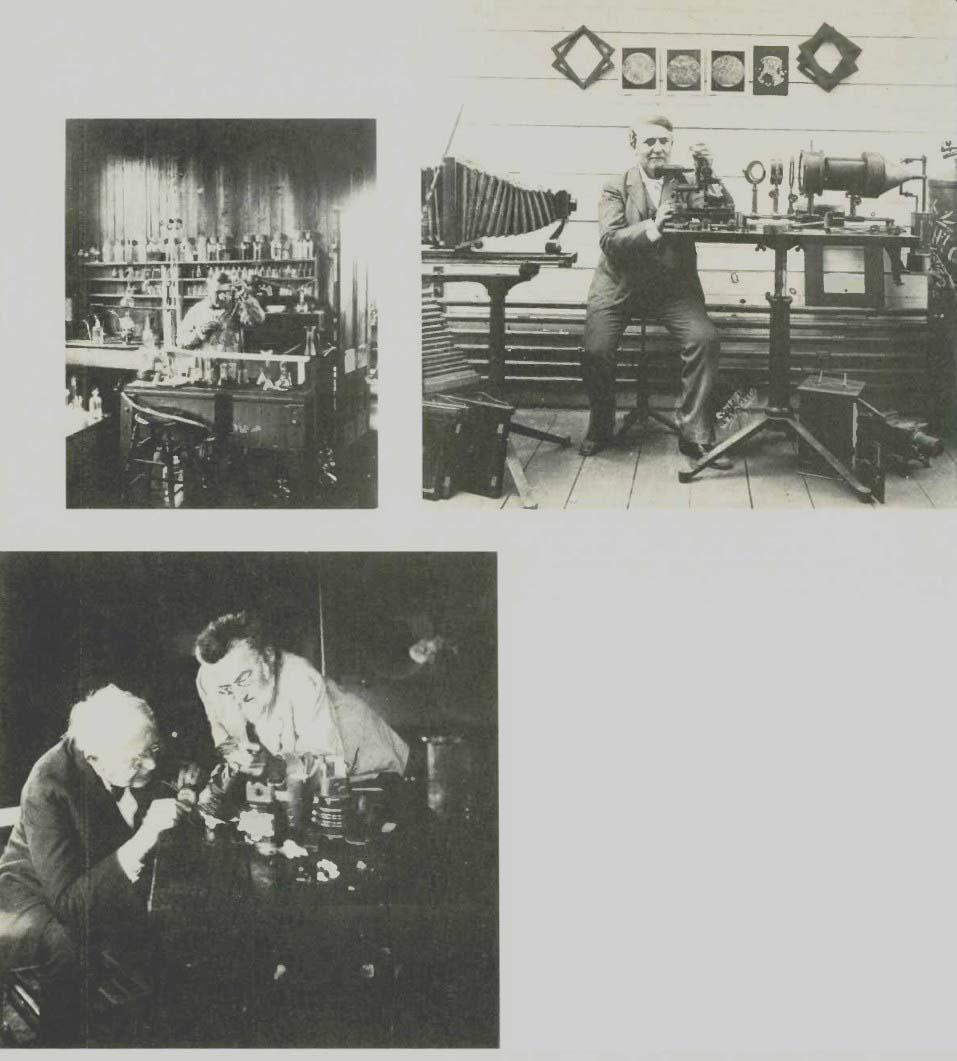

Edison's scientific contributions were certainly not limited to the acoustical -mechanical, as in the case of the invention of the phonograph, and on this page we see him pursuing his significant chemical, optical, and electrical investigations.

The chemistry lab in West Orange was important (as Edison's earlier one at Menlo Park had been) not only for what might be called research in "pure chemistry," but also for developing compounds needed in other work. He tried numerous materials while seeking an appropriate light bulb filament.

Materials from which records could be molded were the subject of almost as exhaustive a research program.

The photo of Edison as chemist was taken in 1890.

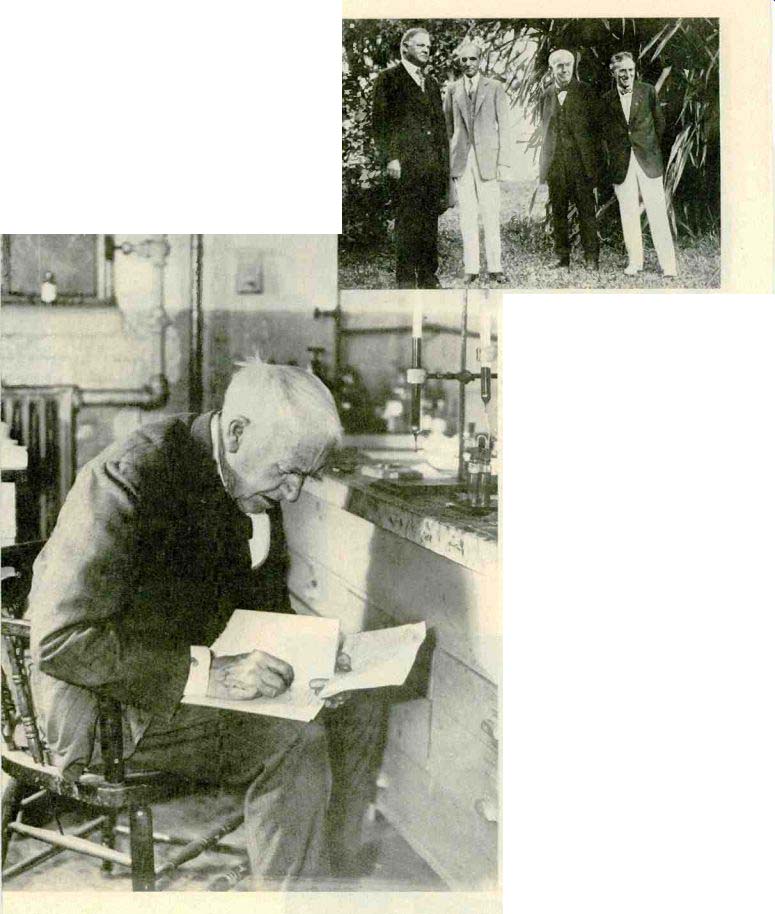

In another part of the West Orange lab, three years later, he is seen with one of his optical experiments. Hanging on the wall behind him are enlargements of photomicrographs. His work in optics led him to pioneering work on the motion picture. As electrician, he was photographed in 1922 with his longtime friend Charles Steinmetz, for years the resident genius at General Electric.

---------------

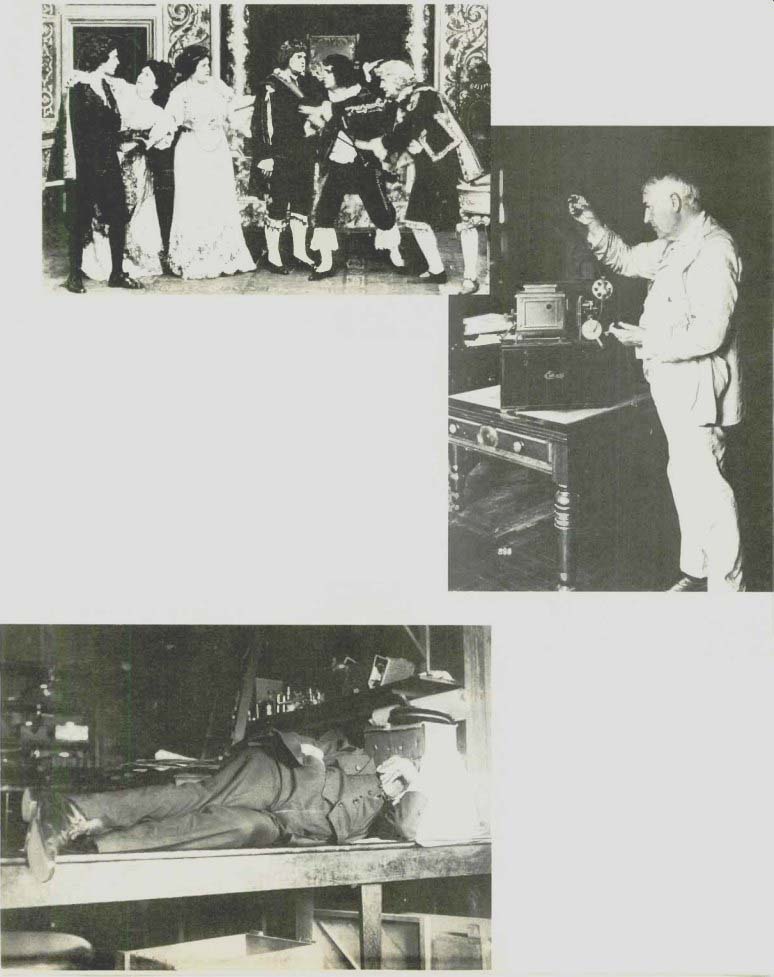

By 1912 Edison had to his credit the sound movie camera (which he called the phonokinetograph) and projector (the come phonokinetoscope is shown at right). That year he made what is probably the earliest operatic film: the Sextet from Lucia (above). The sound was recorded on a cylinder synchronized to the film in the projector. The Lucia excerpt seems to have been particularly dear to Edison; some years later he passed for issue a Diamond Disc with two different recordings of this piece one on each side.

Of these, one cast featured artists of international repute (Giovanni Zenatello, Mare Rappold, Margirete Matzenauer), while one relied on lesser luminaries (like Alice Verlet and Henri Scott), with two artists (Arthur Middleton and Enrico Baroni) repeating their parts on both sides. The film version required photogenic artists; though some also recorded prolifically for Edison, they usually appeared anonymously as members of groups.

Edison was famous for hard work and long hours. lie was equally famous for taking quick catnaps as opportunity allowed. In this 1911 photo he was captured asleep in the lab.

He also kept a cot in his study at West Orange; on this occasion, apparently, Morpheus overtook h m before he could repair to its relative comfort.

-----------------

A man for whom his work was all-important, Edison chose to socialize with those who felt and worked as he did. In the 1929 photograph above, he appears with Herbert Hoover, Henry Ford, and Harvey S. Firestone. Hoover, then President, had come to national prominence as a mining engineer ( Edison also had been deeply involved in mining) and philanthropist. ( Edison's economical concrete house would have appealed to this instinct in Hoover.) Firestone and Edison were, in a sense, competitors for the business of providing tires for Ford's cars; Edison worked for years to produce a rubberlike compound from native goldenrod. At eighty-one (in 1928, left) he was still assiduously making entries in his lab notebooks-much like those from which, elsewhere in this issue, his early sketches of the phonograph are reproduced. He died on October 18, 1931, in his eighty-fifth year.

-------------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1977)

Also see: