The New Releases: Wagner's Masters Get Their Due, David Hamilton; New Life for Louise Conrad, L. Osborne; How Do You Like Your Liszt? by Harris Goldsmith.

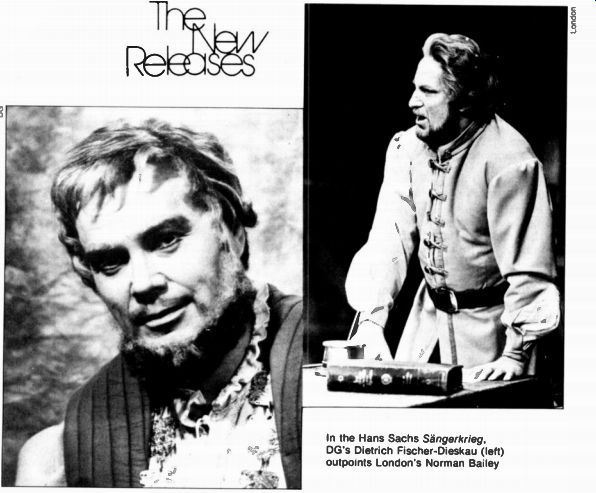

In the Hans Sachs Sangerkrieg, DG's Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (left) outpoints London's Norman Bailey

-----------

Wagner's Masters Get Their Due: Jochum (DG) and Solti ( London) preside over outstanding accounts of Die Meistersinger, each with distinctive strengths.

by David Hamilton

-----------

How WONDERFUL to be confronted with two fine recordings of Wagner's rich and searching comedy at once--and how frustrating! Wonderful, because both of them seem to me markedly superior to any recording of the score made in the last two decades. Frustrating, because this circumstance inevitably means they have had to be heard, and must be written about, in tandem, as in some sense competitive, each coloring one's impressions of the other, raising questions, pointing up deficiencies. And frustrating also, I must add-in fairness both to the recordings and to myself-because each has taken time from further hearing of the other, further hearing that might have made me more confident about expressing my conviction as to which would be more likely to go with me to that desert is land the BBC used to maintain for record reviewers, complete with gramophone and a shelf just wide enough for ten records.

To devote half of such an allotment to a single work may seem extravagant, and in truth I would be hard put to decide between Meistersinger and Tristan, right up to the departure of the boat (although for Tristan, at least, there would be no problem about which recording-the Furtwangler, naturally). But since the boat isn't leaving just now, I'm not about to "check rate" one of these two new Meistersingers. (If you're in the "best buy" market, how ever, the Knappertsbusch set, Richmond RS 65002, would be my strong recommendation-mono sound, not always well balanced, and a trying Walther, but fine work from Gueden, Schoeffler, and Minch, plus Dermota's still unsurpassed David and genial pacing from the venerable maestro.) The Jochum recording followed performances at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, with Placido Domingo and Catarina Ligendza, among others, imported for the sessions. Perhaps for this reason, it has an easier, more natural sense of being played as a drama; there is a spontaneity and warmth here that is less of ten evident in Solti's more concert-like version. The latter's strengths are in the big scenes-especially the gathering of forces in the Festwiese-and, through out, in the orchestral playing. The Berlin orchestra, unfortunately, just isn't as good as the Vienna Phil harmonic-notably a frowsy first horn, intermittently troublesome at the start of "Am stillen Herd," in the Fliedermonolog, and in the Act III prelude. In all fairness, though, most of their work is accomplished enough, full of style and spirit.

Surprisingly, Jochum is usually more successful than Solti at keeping the piece moving; his tempos, chosen down the middle of tradition's road, are less often and more subtly modified. Take the Sachs/Walther dialogue in Act III: Both conductors start off with a nice swing, but with Solti the poco ritenuto at the end of Sachs's first speech assumes major pro portions, the contrast between his genial music and Walther's less active material so overdrawn that by the end of Walther's third speech ("ich filrchr ihn mir vergeh'n zu seh'n") motion has almost entirely disappeared. The scene goes on like this, and cannot help but seem fragmentary, whereas Jochum merely distends his basic tempo slightly and lets the contrast that Wagner has already written into the material do most of the work.

On Jochum's side, too, is a slightly drier, cleaner sound for the orchestra, allowing the rhythmic activity to speak more effectively; the little episode be tween Sachs and David just before the Fliedermono log is a good example of this, with very little musical difference between the two performances-yet the Jochum sounds steadier, more focused, because the repeated rhythms in the orchestra are more explicit (in truth, the snappier delivery of Dietrich Fischer Dieskau plays a role in this too).

On the other side, though, are such matters as the rich, warm Vienna brass, who help Solti make some thing ravishing and memorable out of the Act III prelude, the superb winds of the end of Act II, the full panoply of virtuosity pulled out for the interlude and final scene, where Solti's wonted vigor is very much in evidence and very relevant. The Berlin chorus is quite fine, but the Vienna one is better, while Solti boasts the additional refinement of a boys' choir for the apprentices--and very good they are.

But before totting up pluses and minuses in earnest, we had better consider the casts. The most newsworthy aspect of these recordings is the appearance of Fischer-Dieskau as Hans Sachs, so let me say right off that it seems to me a very great success. Not,

------ Eugen Jochum-warm, characterful conducting.

... of course, in the tonal tradition of Schorr and Bockelmann; he doesn't have the right resources for that. I suspect he has been studying the part for a long time, for it’s a fully formed, highly detailed performance, every line "read" with understanding, every phrase sharply and accurately limned. The voice is light, to be sure, but is used with great skill, so that the climaxes really do count, and the delicate moments are unforgettable: Surely the Midsummer Eve passage in the Wohnmonolog has not been sung as beautifully in decades (the orchestral playing here is really delectable in its lightness and wit, too). He's very much "with" Jochum's rhythmic approach to the score, aiding and abetting the conductor's swing and keeping the textures precise and clear.

London's Sachs is Norman Bailey, a thoughtful and sensitive performer whose voice is, I fear, simply not a very attractive instrument: a thewy, constricted sound that never succeeds in getting free of some apparent jugular impediment. Most of the time, the notes are there, although he fails my standard test phrase for intonation, "stinge dem Vogel nach" in the Fliedermonolog with its alternating Gs and G sharps (need I say that Dieskau passes this with flying colors?). And the delivery of lines is warm, intelligent, if not as detailed as that of the native-German-speaking baritone; on-stage, Bailey is an always interesting performer in this part-but on records he is only partially successful.

Perhaps the greatest surprise is DG's casting of Placido Domingo as Walther, and I think this justifies itself. Even though he did not sing-and never has sung-the part on-stage, he evidently knows quite well what it's all about; he never blunders into a line so that you think of John Culshaw's anecdote about the novice Jago who, halfway through a recording, inquired, "What's all this about a hand kerchief?" The German is oddly formed at times, with over-trilled r's and "Quell" pronounced as "kwell" rather than "kvell," but this is a small price to pay for such firm tone, accurate musicianship, and often elegant phrasing. By contrast, Rene Kollo's por tamentos and scoops grow rather trying, and he seems to be driving his voice even harder here than in the second Karajan recording (Angel SEL 3776, December 1971). There are few complete failures in these casts, but I'm afraid that DG's Ligendza is one of them; this blowsy sound simply isn't an Eva voice, and she de tracts from every one of her scenes by singing pretty consistently out of tune; the quintet is thus rendered fairly excruciating. When reviewing the Varviso/ Bayreuth set last year (Philips 6747 167, April), I suggested that Hannelore Bode's "flatness at the beginning of the quintet could doubtless have been avoided in a studio recording"--and the London set proves it; she makes a much more effective Eva here, if not quite up to the historic heights of Muller (with Furtwangler in 1943, EMI Odeon 1C 181 01797/801, September 1976), Schwarzkopf (with Karajan in 1951, Seraphim IE 6030), and Gueden.

Both Beckmessers own rather imposing voices, not at all the buffo sounds that we have sometimes been offered. DC's Roland Hermann actually sings every thing in the role full voice, without resorting to falsetto even for the top A, and London's Bernd Weikl also eschews most of the traditional squeaks and squawks. I'm all for Beckmesser looking-and sounding-like a fairly normal exemplar of the human race (else how would he have become town clerk?), but Hermann plays it so straight that the choral amuse ment upon his mere appearance for the song contest becomes scarcely credible. Weikl offers just enough spluttering rage in the exchanges with Sachs to sug gest that the deep end is well within Beckmesser's reach. "Lug und Trug! ich kenn' es besser" in Act III, Scene 3, is a good test line; Hermann isn't nearly apoplectic enough, Weikl gets the right tone.

The rich sound and apt conversational tone of Peter Lagger (DG) promise well for Pogner's address, but a severe wobble invades his voice above middle C, and the honors go to Solti's very solid Kurt Moll.

Conversely, DC's Gerd Feldhoff makes an acceptable Kothner, London's Gerd Nienstedt an unpleasantly out-of-tune one.

And that brings us to the below-stairs couples.

Horst R. Laubenthal, Jochum, and the Berlin orches tra among them give such a loving, lovely account of the modes that Adolf Dallapozza's merely efficient David is left far behind, and although the Magda lenes, Christa Ludwig and Julia Hamari, are not easy to choose between in most of the part, DC's Ludwig is the one who can really deliver in the riot scene.

This episode is well done in both recordings but sonically articulated with greater clarity by DG--you can actually hear a startling number of the solo lines-and Jochum saves a little extra for the climax, when the Midsummer's Eve motive soars out in the orchestra, making it overwhelming instead of merely exciting.

As I've suggested, I prefer the DG sound for its clarity, which is enough to compensate for a characteristic bias in favor of the voices by comparison with London's balance. London's stronger bass register is often a plus factor, save when it reproduces all too clearly what seems to be the stamping of Solti's foot.

I don't find any credits for tile players of Beckmesser's lute, but the anonymous DG lutenist, with a gut stringed instrument, discovers some touches of humor in this part that have escaped all his predecessors, as well as his new rival, whose metal-stringed instrument is less attractive and less audible.

One minor matter: The London Nightwatchman, billed as "Werner Klumlikboldt," proves to be two people: Kurt Moll at ten o'clock, Bernd Weikl at eleven. The name, as Alan Blyth in Gramophone has pointed out, is an anagram of the two. If you want to explore their work in these parts further, Moll sang the entire role in the second Karajan recording, Weikl in the Varviso.

Most of the side breaks are standard, and reason ably chosen, but I prefer DC's choice in Act II (after the Nightwatchman has sung and sounded his wrong note) to London's (after his first note, but before the new key to which it pivots has been established). Both booklets include interesting illustrations based on the original 1868 Munich production; as usual, London's printing is poor enough to reduce their value, though fortunately not bad enough to render illegible a fine introductory essay on the opera by the late Deryck Cooke, more detailed and searching than the interesting but briefer one by Martin Cooper in the predictably handsome DG booklet. Peter Branscombe's good translation, al ready used by Angel and Philips, turns up again for DG. while London offers a new, un-credited one (not the same as that produced in 1967 to go with the Richmond reissue of Knappertsbusch); I haven't had time to vet it thoroughly, but a quick check has turned up no major absurdities. Neither company, strangely, includes a word about any of the numerous performers.

From all of this, it’s doubtless evident that I find Jochum's reading the more characterful, the more genial--but I could quite understand an honest preference for Solti's more reserved and magisterial approach. Both are remarkably fine accomplishments.

---------------------

WAGNER: Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg.

(1) (2) Eva Catarina Ligendza (s) Hannelore Bode (s)

Magdalene Chnsta Ludwig (ms) Julia Haman (ms)

Walther von Stolzing Placid Domingo (t) Rene Kolto (t)

David Horst R Laubenthal (1) Adolf Dallapozza (1)

Kunz Vogelgesang Peter Maus (t) Adalbert Kraus (t)

Balthasar Zorn Loren Driscoll (t) Martin Schomberg(t)

Ulrich Elselinger Karl-Ernst Mercker (t) Wolf Appel (t)

Augustin Moser Hans Sachs Martin Vantin (0 Michel Senechal (1)

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (b) Norman Bailey (b)

Sixtus Beckmesser Bernd Weikl (b) Roland Hermann (b)

Fritz Kothner Gerd Feldhoff (b) Gerd Nienstectt (bs-b)

Veit Pogner Peter Lagger (be) Kurt Moll (bs)

Konrad Nachtigall Roberto Bariuelas (b) Martin Egel (bS) Hermann Ortel Klaus Lang (bs) Helmut Berger-Tuna (bs)

Hans Schwarz Ivan Sardi (be) Kurt Flydl (be)

Hans Foltz Miomir Nikolic (be) Rudolf Hartmann (be)

Nightwatchman Victor von Halem (be) "Werner Klumlikboldt" (1) Chorus and Orchestra of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, Eugen Jochum, cond. [Gunther Breest and Hans Weber, prod.]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2713 011, $39.90 (five discs, manual sequence).

(2) Gumpoldskirchner Spatzen, Vienna State Opera Chorus, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Georg Solti, cond. [Ray Minshull, prod.]

LONDON OSA 1512, $34.90 (five discs, automatic sequence).

Tape: 41 OSA5 1512, $39.95 (four cassettes).

--------------------

New Life for Louise

by Conrad L. Osborne

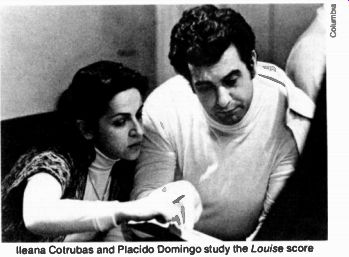

----- Ileana Cotrubas and Placid() Domingo study the Louise

score.

Columbia restores Charpentier's treasurable working-class drama to the catalogue with Placido Domingo aptly cast as Julien.

IT HAS BEEN a pleasure to encounter again this lovable and touching opera. The present recording has its drawbacks as well as some important strengths; the real point is that it puts a sonically up to-date, complete performance of Louise into the catalogue.

Louise is the only successful example of French verismo, if by this term we mean to identify not only works of realistic background and psychological truth-to-life (Carmen would certainly qualify) or shock-operas whose dramatic outlines and musical gestures remind us of Cav and Pag (La Navarraise), but works that seek to dramatize the conditions and aspirations of very ordinary people, and to convey these concerns in a language of popular immediacy.

There is much about Louise to remind us Americans of our own socially committed theater of the 1930s, and it has been the opera's recent fate to fall victim to some of the same careless habits of thought we tend to apply to plays of that genre: We see them as bound to the social and political specifics of their time, to a tract mentality, and to an expressive naiveté we enjoy looking down upon. And so some of them are. But (as I was reminded last spring by the McCarter Theater's superbly cast and directed revival of Awake and Sing) the best of these works are grounded in a truly sensitive observation of ways of human interaction which, if not "universal," are certainly common to cultural donnees we have by no means sloughed off.

Thus, Louise is in part about the lot of the urban workingman; in part about a young woman's difficulty in establishing an identity vis-à-vis restrictive parents or a dominant lover; in part about the over whelming nature of the modern city, whose powers of magnetism and alienation seem so tightly knit together; in part about the qualities of what we now call the nuclear family and the patterns of tyranny and rebellion we so often see as native to it; and in part about the very perplexing question of just what does constitute personal "freedom." The circum stances of the piece could well be directly translated to those of the contemporary conservative blue-collar family whose daughter vanishes into SoHo with a self-styled poet for a lover.

And Charpentier deals with these circumstances in a way that is concrete and specific, and that allows for the ambiguity of the arguments. The ways of life represented (the narrow domestic routines of the poor family, shown in Acts I and IV; the marginal existence of the street inhabitants and the work life of the dressmaker's sewing girls, shown in Act II; and the subculture of the Bohemians, represented in Acts II and III) are all sketched in precise, selective detail.

And though it’s clear that the author/composer shares Julien's belief in "the sovereignty of love," and that "Every being has the right to be free/Every heart has the duty to love," the conflict between children and parents is seen as a genuine emotional problem.

The basic conflict is the classic one of father vs.

suitor for the love and loyalty of a daughter. To sharpen it, Julien is represented as an outsider to, and rebel against, the world of the parents, someone they cannot understand and who does not meet their canons of "respectability." In the early scenes, the father is shown to be capable of some tenderness and understanding; he is a man of feeling, who acts as mediator between Louise and the mother, who is quite unsympathetically shown (her overriding in tent is the preservation, by harsh means, of a ritual familial togetherness). We appreciate the touches of delicacy and humor in the father's character, sympathize with his bitterness over an aging laborer's lot, and feel that the love between him and Louise is genuine.

But because the father's feelings are accessible, it’s he who finally drives Louise from the house, de spite the mother's efforts to calm him (she even calls him "Pierre" twice-the only time in the opera that anything so personal as a first name passes between the parents). Along with Louise's rightly famous aria "Depuis le jour," long stretches of the father's role ("Les pauvres gens peuvent-ils etre heureux?," "Voir naitre une enfant," and the moving Berceuse) contain the most deeply felt music in the opera, and the last confrontation between father and daughter can be wrenching.

It’s always interesting to observe where a plot stops. In this case, it’s at the point where Louise vanishes into the city night, and the father, stretching out his fist at the suddenly extinguished mirage of noises and lights that has lured her away, despairingly names his true antagonist: "0, Paris!" For the city, with its "apotheosis of light," its variegated and anonymous ways of existence, its sensuality, is a metaphor for the life of choice, of adulthood. And we are reminded we have watched only the first exciting but terrifying step of Louise's life, for which Julien is merely the catalyst. To this point, she has simply substituted his catechism for her parents': She can do no better than to answer her father's arguments by quoting Julien, and the "freedom" which Julien claims for her against the father is that of "electing the master of your destiny." So, while Julien is the bold and flattering first lover who lends Louise the courage for her necessary first step, it’s inconceivable to us that her growth should stop here. Finally, the father is right-it is not so much Julien she chooses, but the "Paris" of infinite possibilities, pleasant and otherwise.

Living stuff for our audiences, I should think. And Charpentier's score has such a wealth of harmonic and orchestral color-as descriptive theater music, it’s truly expert and sometimes magical. While the melodic spans are generally short, their employment as motivic devices is shrewd and often haunting. This is true not only of the vendors' cries that recur to such atmospheric effect (and almost always avoid the cliché moment for doing so), but of such simplicities as the little flourish for the goat-herd's flute, which at first seems purely a daub of primitive hue, a la Cante loube's orchestrations of Auvergne songs, but then quite unexpectedly puts a breathtaking crown on Louise's first confession of love ("... je serai to femme! Julien! mon bien-aime," near the end of the first tableau in Act II), wonderfully sweet and melancholy.

The vocal writing is always competent from a technical point of view (though challenging), but is uneven in its effectiveness. In dialogue exchanges, especially of the more vehement sort, the composer tends to fall back on solutions that are not quite convincing either as "unending melody" or as "extended speech"-these passages have a dogged, forced air that reminds us all too much of more recent works.

But in sections of a more tender or charming nature, we are reminded, in a most positive way, of the Massenet heritage, and when Charpentier sets himself his biggest challenge-the latter portion of the Act III love duet with the city visually and aurally present, a dangerous concept-he rises to it thrillingly.

The choral setting is splendid almost throughout: The Bohemians have exhilarating moments with their raucous song in Act II, and again in the full blown march and pompous presentational music of the Coronation of the Muse. I have also come to value the loving musical drawing of a chatty work day at the dressmaker's, which at one time seemed quite banal and incidental to me.

Discographically, there is not much to report about Louise. The touchstone recording, dating from the early 1930s, is an abridged version (extended excerpts, really) made by Columbia in Paris. Well con ducted by Eugene Bigot, and featuring three admirable French artists (the soprano Ninon Vallin, tenor Georges Thill, and bass-baritone Andre Pernet), it should be heard by anyone who loves either Louise or French lyric art; but with its cuts and its tubby sonics it’s hardly satisfactory as a complete performance of the opera. Once available on LP in the Entre series, it has more recently been imported as EMI Odeon 2C 153 12035/6. A complete performance (actually embracing a few cuts totaling perhaps six or seven minutes) was released here on Epic in the mid-Fifties. It had a solid conductor (Jean Four net), good French veterans as the father and mother (Louis Musy and Solange Michel), and strong work in some of the small roles. But it also had edgy, cramped mono sound and lead singers who were scrappy but rather fatiguing to the ear.

The current recording is thus the first in stereo, and the first to take on an international aspect in its casting and provenance (it was recorded in London, with English orchestra, chorus, and supporting singers). I cannot summon much real enthusiasm for either performance or recording, but I am sure it’s good enough to convey the essential qualities of the work; its failures are largely those of omission.

I suppose it’s futile to pine over the absence of forces that have Louise in their blood-even in France, the piece has dropped from the repertory, and the international houses no longer tackle it (though the New York City Opera revives it from time to time, and to good audience response despite mediocre casting and production). Still, it’s clear that what is missing from this production is the kind of grasp that goes with familiarity.

A good conductor can study and master a score technically, a good orchestra can read it and get on top of its notes, good singers can learn roles and sing them in vocally, and a producer can look through a score and come up with casting that approximates its requirements, and all this will add up to a good, professional start on an opera. The lessons learned from the experience, the flexibility gained from repetition, the adjustments made after the initial fact-all these constitute the very real strengths of "tradition," of classical repertory, and they pay off disproportionately in a special piece like Louise. Contemporary recordings seldom have the benefit of such a history, and it's becoming a scarcity in the theater too.

The one real casting inspiration is Placido Domingo as Julien-the role and the voice are made for each other, and he gives a splendid first performance.

He is in his best voice here, and the music is perfectly set up to take advantage of his rich middle and ringing G-to-B-flat top, where he tirelessly pours out ex citing, refulgent sound. The role demands little of the delicacy of most French writing-a good romantic/ heroic voice and a decent basic legato will produce a big effect in the part, and Domingo certainly obliges.

It’s clear it's not under his skin yet, for he does little with the character, with words or real finish of phrase-there is hardly a change from his declarations of love for Louise to those of his contempt for her parents and back again. That will come with direction and stage performance, in the unlikely event that ever happens.

Ileana Cotrubas is a new artist to me except by reputation-I hadn't caught up to her previously, live or recorded. She has a pretty lyric soprano voice with a warm, floaty timbre in the middle. Like so many modern voices of this type, it’s rather weak in the lower-middle area, and somewhat restricted in color, so that the over-all effect in this demanding role is a bit careful, though attractive in a general way. A basic musical sensitivity comes through, but not much individuality or dramatic vitality. Like most sopranos (including Vallin), she is extended by the final scene, and happier in the purely lyric portions. Altogether, an equivocal impression, though by no means an entirely negative one.

Gabriel Bacquier and Jane Berbie are obvious choices for the father and mother, but in the event neither turns out especially well. Bacquier is a fine artist still, but has been recorded late in this role, which poses major singing demands. The casting of the father has a strange history, ranging from the lightest of French baritones (e.g. Fugere, Gilibert) to true basses (Pinza, Rothier), with a number of the French light bass types in between (Vanni-Marcoux, Dufranne, Pernet) as well as more straightforward medium-weight baritones (Musy, Brownlee). The singer is expected to have clarity and strength in the occasional high stretches, but to spend most of his time below middle C; what is suggested is a baritone with a classically French lucidity of tone in the lower range, the sort that will carry without becoming weighty, or else a bass with an unusually easy and commanding top.

Bacquier is a baritone, but one whose top has grown increasingly chancy and whose tonal color has become prevailingly dark; he has the drawbacks of the bass without the advantages. He sings the role gently and makes a lovely expressive effect at such moments as the conclusion of his pleas to Louise in Act I ("O mon enfant, ma Louise!") or at the opening of "Voir naitre une enfant"; at these points, his artistry tells. But he hasn't really the solidity or bite to bring the stronger side of the character to life, and he evades the top at several key points. Musy, recording the part at a comparable stage of his career, was more able-bodied.

Berbie is another good artist who doesn't seem at her best. The voice sounds a bit stiff and narrow, and does not sit comfortably on the low-lying tessitura.

She rather forces the more vehement declamations, but makes a better effect with the plea to Julien at the end of Act III. Among the army of supporting singers, the out standing impression is made by Michel Senechal in his double assignment. For the King of the Fools, one could wish for a little more vocal heft, but he brings an easy expertise to both parts. In general, the men make a somewhat better impression than the women, for the simple reason that almost all the fe male parts require projective strength in the lower range, and are cast with singers who don't have it -- they're singing in the cracks. Eliane Manchet, the Camille, sounds charming until required to sing above the staff near the end of her song. Meriel Dick inson and Shirley Minty make positive effects as the Forewoman and Gertrude.

The men are also cast on the light side, but get away with it better. The very important role of the Ragman, f or example, should be a true bass-this is suggested by the nature of the character, by the tessi tura he sings, and by the constitution of the accompaniment (brass and low woodwind). John Noble is a lightish baritone, but colors and inflects well enough to be acceptable. Still, Epic's casting of Gerard Serkoyan demonstrates the difference, and in fact the older recording has a greater general rightness in these roles than the new one.

Georges Pretre, whose reputation has fallen on evil days, is nevertheless an interesting and often effec tive conductor who has been responsible for some excellent recordings. He is erratic, however, and a re current problem seems to be a reluctance to trust the music rhythmically in more subdued or sustained passages. For me, for instance, he seriously compromises the opening of Act II by adding a stringendo to the crescendo in the fifth bar of the awakening motif (an andante tranqui/lo e maestoso, and both those qualities are effectively banished, for no good musical reason that I can see). Throughout, there is a tendency to skate impatiently through such moments without giving them time to unfold, to assume their proper weight.

On the other hand, he is one of the few contemporary conductors with an ear for lushness of color, a sensitivity to the textures of this sort of music, and as a result there are some quite gorgeous moments. The more vital, extroverted passages have some real excitement, and he secures a lovely delicacy and transparency when needed. The orchestra plays very well for him, and the choral singing is first-rate.

The recording of course captures more of the score's color and fullness than do the older ones, but it’s only fair by current standards, missing any real breadth or weight of sound. I don’t at all care for the runny textures and strange balances of the street scene-the vendors' voices don’t sound off, but only separate (the same is true of the supposedly distant chorus in Acts III and IV), the worst instance being that of the Carrot Vendor: The whole point is that he is crying out at the top of his lungs, but at a consider able distance (f, suggests Charpentier), whereas he is clearly not more than two feet away, crooning. All the staging here sounds more like mixing, and it's pretty unconvincing. Some detail is dropped out entirely--the sound of the sewing machines in Act II, Scene 2, is hardly distinguishable, for instance. Too much electronic sophistication, too little dramatic and musical common sense.

The accompanying booklet offers a stilted translation and sketchy notes; if you can, dig up Epic's, with a stilted translation and far more complete notes, including a very good biographical essay by:

Jean Desternes.

CHARPENTIER: Louise.

Louise Camille Irma The Mother Julien Ileana Cotrubas (s)

Bane Manche1(s)

Lyliane Guitton (ms)

Jane Berbie (mS) Placid() Domingo (t)

The Noctambulist. The King of the Fools Michel Senechal (1)

The Father Gabriel Bacquier (b)

The Ragman John Noble (b)

(plus numerous smaller parts)

Ambrosian Opera Chorus, New Philharmonia Orchestra, Georges Pretre, cond. [Paul Myers, prod.] COLUMBIA M3 34207, $20.98 (three discs, automatic sequence).

+++++++++++++++

How Do You Like Your Liszt?

Carlo Maria Giulini's conducting and the pianism of Horacio Gutierrez, Gyula Kiss, and Lazar Berman highlight a worthy crop of concertos.

by Harris Goldsmith

WE HAVE AN EVENT surely worthy of some note: three new discs that include the Liszt First Piano Concerto, all warmly recommendable.

The new contenders are: from Angel, Horacio Gu tierrez and Andre Previn (with the Tchaikovsky First Piano Concerto as coupling); from Hungaroton, Gyula Kiss and Janos Ferencsik (with the Liszt Totentanz); and from Deutsche Grammophon, Lazar Berman and Carlo Maria Giulini (with the Liszt Second Concerto). The young Cuban-American Gutierrez deserves pride of place, since he is making his recorded debut.

He sounds like an impressive virtuoso, with a lean, silvery tone, an acute sense of line, and, when appro priate, caressing rubato. His tempos are generally brisk, but there is much expressive leeway too.

The Liszt concerto gets an interpretation in the best conventional manner. The Tchaikovsky concerto is trim, elegant, often exciting, and pleasingly (not sloppily) expressive. The octave passages carry a demonic energy reminiscent of Horowitz, in that electricity and edge, rather than bronzen weight, ani mate them. This is a most impressive introduction to a new artist, and I look forward to hearing Gutierrez in other literature. He seems to have grown immensely since I heard him in recital at Hunter College some years back.

Previn supports both concertos admirably: The London Symphony's work is supple and finely nuanced, and all I can cavil at is a tendency for rhythm to go slack. This is most apparent in the second movement of the Tchaikovsky, which Previn molds according to casual "tradition" rather than ac cording to the composer's Andante semplice marking. Angel's sound is of the moderately distant variety, but clarity and detail are not harmed by the reverberant ambience.

The Hungarian Gyula Kiss is a more Beethoven oriented sort of Lisztian. Particularly in the concerto's slow movement, he gives the music a kind of passionate vehemence and angularity, and in general his approach seems to be harmonically oriented--in other words, he maintains a firm underpinning in stead of going wherever a melodic flourish leads him.

It works well, for Liszt did indeed have a certain rigor in his musical makeup, deriving from Beethoven and leading to Bartok. The Kiss/Ferencsik Totentanz is interesting: a strong, clean-limbed interpretation lacking the breathtaking velocity of the Watts/Leinsdorf (Columbia M 33072) but with a compensating sober intellect that is, in its way, equally persuasive.

Hungaroton's recording is easily equal to that of the others in this group-a firm, plangent, mellow piano; closeup instrumental perspective (the triangle, very close, has unusual body as well as brilliance); and silent surfaces. My only criticism, which applies to the Angel as well, is that the piano occasionally blots out an important woodwind solo, though never to a musically offensive degree.

With all due respect to Berman, who plays both Liszt concertos with taste, color, and superb every note-in-place command, it’s Giulini's orchestral contexts that give the new DG disc its strong character. One does not think of Giulini as a Lisztian, and it’s therefore a pleasure to hear how explicit his direction is. Tempos are rather slow, with a firm, constant pulse taking precedence over garish outbursts. Both concertos as a result emerge in a dignified, structural manner suggestive of the best Klemperer. The instrumental detail is marvelous, the result of musical in tent rather than merely skillful microphoning. The Vienna Symphony is not the glossiest of orchestras, but it gives its utmost under Giulini's inspired guidance.

It’s unusual to hear conductor-dominated performances of the Liszt concertos, but when the piano-playing is so accomplished and put to such good use, the adjustment is quickly made. Nevertheless, I must note that Berman's pianism seems a shade stolid, lacking that last touch of magic that Richter and Vasary, to name just two of the really memorable recorded interpreters of these concertos, achieved.

Perhaps some of the constraint is due to the recorded sound. While very clear, it has a problem rather opposite to that of the Angel and Hungaroton engineering: The piano seems to have been artificially limited to prevent its swamping orchestral instruments at climaxes.

Still, whatever the cavils, all three of these records warrant attention for the seriousness and quality of both playing and recording.

LISZT: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 1, in E flat.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 1, in B flat minor, Op. 23. Horacio Gutierrez, piano; London Symphony Orchestra, Andre Previn, cond. [John Willan, prod.] ANGEL S 37177, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc). Tape: WO 4 XS 37177, $7.98.

Liszt: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 1, in E flat; Tot entanz. Gyula Kiss, piano; Hungarian State Orchestra, Janos Ferencsik, cond. [Janos Matyas, prod.] HUNGAROTON SLPX 11792, $6.98.

Liszt: Concertos for Piano and Orchestra: No. 1, in E flat; No. 2, in A. Lazar Berman, piano; Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini. cond. [Gunther Breest and Werner Mayer, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 770, $7.98. Tape: 3300 770, $7.98.

-------------

(High Fidelity, Feb 1977)

Also see: