The New Releases:

Reopening the Meyerbeer Case, Patrick J. Smith; Of Fiddles and Fiddlers, Irving

Lowens/Shirley Fleming; Wagner's Roman Colossus, David Hamilton

Bringing Prophete to life: Henry Lewis and Renata Scotto

Columbia Reopens the Meyerbeer Case

The vitality of Henry Lewis' conducting and the conviction of Renata Scotto's singing help bring Le Prophete to life.

by Patrick J. Smith

THE GRAND OPERAS of Giacomo Meyerbeer are one of the last major outposts of unrecorded nineteenth century opera. We have had only a good, if equivocal, performance of the most famous of them, Les Huguenots, from Richard Bonynge (London OSA 1437, January 1971, still in the catalog). Le Prophete (1849) stands between Huguenots and L'Africaine; despite a lot of listenable music, it is the weakest of the three. Columbia's new recording, however, should win the composer some converts, for it is a generally strong, and definitely recommendable, rendition.

Scribe's libretto tells of the Anabaptist uprising in the 1530s in Germany, centering on the false prophet, Jean. The plot, however, has little to do with the historical facts, and is history tailored to the nineteenth century grand-opera sensibility. Thus Jean is a simple, God-fearing innkeeper, who loves his mother and his fiancée (in that order), and who is used as a pawn by a trio of bogus "monks." Jean is one of Scribe's best-drawn characters (although his mother love stifles the libretto), shown as an honest bourgeois inflamed into action by the injustice and cruelty of the nobility and manipulated by opportunistic power-mongers. He continually has doubts as to his actions and the rightness of his cause, but his coronation brings him to the point that he believes that he is really the son of God-at which precise moment, in the theatrical masterstroke of the opera, his mother recognizes him. He then realizes the sins of his pride and his lust for fame, and destroys himself and his enemies in a final conflagration.

Scribe fills out this portrait of Jean (a forerunner of Mussorgsky's subtler false Dmitri) with his usual flair for the grandiose in terms of scenic splendor and theatricality, building his work through a series of "numbers"-arias, duets, and ensembles-to its dramatic high point in the fourth act, as in Huguenots. In addition to Jean, there are three other characters: the Anabaptist trio (a three-headed exemplar of sleazy evil), his fiancée Berthe, and his mother Fides. Fides, rewritten and expanded for Pauline Viardot-Garcia, is one of the major mother figures in all opera, and her sentimental aspects are constantly to the fore. In deed, this feature of the libretto is today the most dated, for what was of considerable power in the nineteenth century is now not only sentimental but lachrymose, threatening to turn Jean into a mama's boy and his mother into an annoying kvetch.

Which brings us to the music. There is no question that Meyerbeer is of prime historical importance as a composer. To listen to any one of his later works is to realize the extent of his influence: His ideas were stolen by almost every subsequent opera composer of the century. The range of his musical effects is extraordinary-time and again his response to the musical or dramatic demands is arresting.

Why, then, have his operas never moved into the repertory? Not, I submit, because there are no singers today to do him justice, although that is a factor. Op eras of other composers-Verdi and, pre-eminently, Wagner, to cite two-can be put across without top notch singers. But Meyerbeer lacked that final ounce of talent-that final ounce that a lesser musical mind like Donizetti had.

Meyerbeer's music is essentially short-winded, in the span of his musical ideas and in the span of his imagination. Many of his individual "numbers" are good, and some are outstanding, but the underlying feel is of a craftsman carefully shoring up his talents rather than a genius profligately spreading his around. Also, his ideas (as Wagner noted) do not have the breadth and depth that the form of grand opera required. Quite often the tunes seem rooted in opera comique, and if they have more character and muscle than, say, the tunes of Auber, they do not except in certain instances, such as the classic fourth act of Huguenots--assume an overriding importance of a kind that even Donizetti could command. As with Liszt, the intellectual reach was greater than the musical grasp-and, as with Liszt, there was added an element of pandering to a public.

Le Prophete, no less than any of his grand operas, is a fascinating documentation of Meyerbeer's strengths and weaknesses. Take the trio bouffe in the third act-a drinking song out of opera comique whose verse text exults in the slaughter the Anabap tists will wreak when they capture Munster. Yet the circumstances of the scene and the hypocrisy of the Anabaptists (portrayed in the vocal line) combine with the insouciance of the music to make a highly ironic statement (one that did not escape Verdi when he wrote Ballo in maschera). On the other hand, the "big tune" of the fourth-act ensemble of recognition and rejection-the high point of the opera-while sticking in the mind is a tune of utter triviality. It destroys the moment: Something far stronger is needed, and Meyerbeer's superior craftsmanship will not suffice. Further, the fifth act is a distinct letdown too long and musically undistinguished to follow the fourth.

What keeps Meyerbeer's operas moving is the constant rhythmic vitality (rather than any melodic sweep) of the numbers. Meyerbeer loves to use ac cents, short motifs, notes separated by rests and such musical devices as a kind of Scotch snap to give the music a verve and sparkle. The justly famous Patineurs ballet scene contains an unbroken stretch of Meyerbeer at his best. And here Henry Lewis con tributes to bringing Meyerbeer's music to life, for his steel-sprung reading propels the music forward. It is a rather fast performance (a bit heavy-handed in the ballet music), but one that does justice to the score. I liked certain of his ideas, such as performing the familiar Coronation March not as an expansive pre Aida processional, but as a clangy, circusy event (en hanced by close-miking), perfect in its tinsel superficiality for the entrance of the false prophet.

The best singing comes from Renata Scotto as Berthe, which may be paradoxical in that Berthe has always been thought the weakest drawn role. But Scotto sings with an ease and familiarity with the music that is amazing, given its infrequency of performance. She shapes the phrases with an unerring rightness and controls her sometimes hard-edged soprano so that it becomes a French-sounding instrument of lovely focused tone, yet with plenty of vocal reserve for the climaxes. Her duets with Marilyn Horne are the vocal high spots, and her fiery "cabaletta" in the Act IV duet (which strongly reminds me of the Rigoletto "Si, vendetta" duet) is electrifying.

Her one weakness is a habit of gliding over words in order to phrase, although when she does, for dramatic purposes, choose to enunciate, her French is exemplary. I hope she can be persuaded to sing more of the French repertory.

Horne sings Fides with a clarity of tone and an ac curacy of pitch that mercifully mitigate the pathos of the role. The voice, however, no longer has that rich ness it once did, and it must be said that, although she sings her big set pieces very well, they lack an urgency of communication. Next to Scotto, Horne seems a little distant.

James McCracken's tenor has always been a problematic instrument, and it is here in rather parlous condition. His singing is throughout effortful, of little beauty, as if pushing the notes past an unwilling throat. McCracken's tremolo now borders on a trembling, and the voice is incapable of legato (as the demands of the Act H pastorale attest) or of singing under a forte. Because of, this latter fault, he resorts to a type of head-tone falsetto for some passages.

Since the sounds produced are never integrated with the rest of the voice, this singing results in some very weird and unworldly effects. The best that can be said is that McCracken does project a forcefulness, even though it is one that calls attention to McCracken's difficulties rather than elucidating the role of Jean.

Of the three Anabaptists Jerome Hines, who has the most to sing, displays a spread tone and a gruff ness that work pretty well in his big aria (a rerun of Marcers"Paff, poff" in Huguenots); I wish he could have recorded the part a decade or so ago. Jean Dupouy should be singled out as a first-rate character tenor, and the chorus is fine.

The opera is presented substantially complete, the major cuts being of the second verse of the pastorale and in the shortening of the chorus in the final scene The sound on the review acetates is very rever berant, with some pre-echo.

MEYERBEER: Le Prophete. Berthe Fides Jean de Leyden Renate Scotto (s) Marilyn Home (ms) James McCracken (t) Jonas Jean Dupouy (t) Zacharie Jerome Hines (bs) Mathisen Christian du Plessis (bs) Count Oberthal Jules Bastin (bs) Ambrosias Opera Chorus, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Henry Lewis, cond. [David Harvey, prod.] COLUMBIA M4 34340, $27.98 (four discs, automatic sequence).

+++++++++++

Of Fiddles and Fiddlers (and Friends)

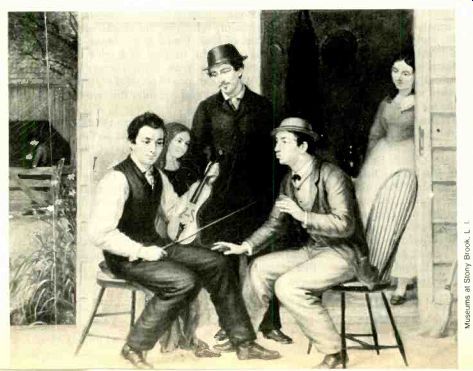

I. William Sidney Mount's "Cradle of Harmony": Is this any way to build a fiddle?

by Irving Lowens

FEW MUSIC-LOVERS are familiar with the name of William Sidney Mount (1807-68), but it is very familiar to connoisseurs of American art, who cherish his scenes of antebellum American life and consider him one of the finest of our early painters. Except for frequent visits to New York City, Mount spent his entire life in or about the village of Stony Brook, Long Is land, and about three-fourths of his known work may be found in and about museums in his home town.

Almost matching his passion for the paintbrush was his passion for the violin and for fiddle music, a fact known to the public not at all, but very well known to a few multidiscipline specialists. Among the latter is music and art critic Alfred Frankenstein, who has spent many years of his life investigating Mount's and who provides the illuminating brochure included with Folkways' recording of fiddle music.

Throughout Mount's adult life, he delighted in playing the violin for country dance parties and for home entertainment. He also assembled an enormous collection of fiddle music, most of it in manuscript. But of even greater interest is the novel, extraordinarily sonorous new type of violin that Mount designed, an instrument he poetically named "The Cradle of Harmony." His own description of his creation, as set down in his patent application of June 1, 1852, cannot be improved upon: "The nature of my improvement consists in the peculiar form in which I construct the back of the instrument, or that part which receives the strain of the strings when they are tightened in the process of tuning the instrument. In the construction of all stringed instruments heretofore made, the form of the back has either been convex or flat, and hence in the process of tuning the instrument by tightening the strings the effect has been to strain or bend the back, and also, as an inevitable consequence, so to compress the fibers of the wood composing the sounding board in front as to alter, interfere with, or impair its sonorous and vibrating qualities.

"To overcome this difficulty, I constructed the back of the instrument, or that part which is strained by the tightening of the strings. in a concave form, so that a convex surface is presented in front toward the strings. By this form of construction when the strings are strained in the process of tuning, the effect is to lengthen instead of shorten the lower line, and thus, while the back of the instrument is relieved from the strain to which it would otherwise be subjected, the compression of the wood composing the sounding board is entirely avoided.

"Constructed in this manner, the back and sides of the violin, by reason of the concavity, receives the strain of the strings when tightened, and the greater shortness of the sound post increases the vibration of the sound board, making the tone of the instrument more sonorous, rich and powerful." Just so. And increased power was very important to Mount, since a lone fiddler, playing for country dances in an atmosphere of stamping feet and shouting merrymaking, needed all the volume he could get.

William Sidney Mount's oil painting Catching the Tune (also known as

Possum up a Gum Tree, after the folk tune) shows the fiddler holding

an instrument designed and made by Mount himself.

Mount's Cradle of Harmony remains extant in only three exemplars: the Patent Office model manufactured by James H. Ward, a New York City carpenter, now on display in the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C.; another made by James A. Whitehorne, who was (like Mount) a painter by trade; and a third fabricated by Mount's nephew Thomas Shepard Seabury, who worked in a carriage factory. No Cradle of Harmony was ever built by a professional instrument-maker.

The Seabury instrument, dated 1857, is the one used by Gilbert Ross in this recording of thirty-five fiddle tunes selected from among the thousands Mount copied and collected from printed and oral sources. He developed the habit of exchanging tunes with another nephew, Robert Nelson Mount, who later became a professional fiddle-player, but, oddly enough, Mount does not seem to have composed many tunes himself. The collection includes only a single Mount original, "In the Cars, on the Long Is land Railroad." On the manuscript, he wrote: "Stony Brook, Dec. 4th & 5th, 1850, by Wm. S. Mount." What is the correct way to' play these tunes? Mount describes his method in a letter written on February 4, 1841, to his nephew Nelson: "Take out your old box and go at it, pell-mell.

Some parts of the strains you must play softer than the others, particularly the Minores, they are beautiful. Play some of the strains in octaves above and below, at leisure. In shifting, slide your fingers up and down. You know what I mean. Let your two first fingers work up in playing the whole set. You can make var[iations] as you play it." That's almost exactly what Ross does. Ross, by the way, is much better known as a concert violinist than as a country fiddler. A pupil of Leopold Auer, he was the founder and for more than twenty years the first violinist of the University of Michigan's Stanley Quartet. "The classical violinist does not forget his Bach and Mozart, his classical indoctrination," Ross says. "[He] only lays them aside for the moment and succumbs unabashedly to the spirit of Stony Brook's Thursday night parties. He 'hauls a tune now and then in the old-fashioned way,' as Mount wrote, and tries to heed (though not too literally) Nelson Mount's advice to his brother: 'Until then you may saw away.' " Altogether, this is a fascinating exploration of a little known byway in the history of American mu sic, beautifully performed, intelligently chosen, and succinctly described. And I might mention that Frankenstein's William Sidney Mount: A Documentary Biography should be in print (from Abrams) by the time you read this. I've been waiting for it to appear for about fifteen years, and "The Cradle of Harmony" has sharpened my appetite considerably.

This is surely one of the most delightful curiosities spawned by the Bicentennial.

THE CRADLE OF HARMONY: William Sidney Mount's Violin and Fiddle Music. Gilbert Ross, violin. FOLKWAYS FTS 32379, $6.98. Willet's Hornpipe; 'Tis the Last Rose of Summer; Waltz; Merry Girls of New York; Yellow Hair'd Laddie; Stony Brook Moonshine; Yankee Hornpipe; Birks of Invernay; Brown Polka; In the Cars, on the Long Island Railroad; twenty-five more.

++++++++++++++++++++

II. Bach's violin-and-harpsichord sonatas: What exactly do you play them on?

by Shirley Fleming

LAST SEPTEMBER in these pages I discussed the Eduard Melkus/Huguette Dreyfus Archiv release of the Bach sonatas for violin and harpsichord and deemed it a respectable, uncolored presentation and just a bit dull. My vote at that time went to Menuhin, partly because of his personal persuasiveness in the music, partly because he assigned a viola da gamba to reinforce the bass line, as Bach directed.

Now the plot thickens, in the form of three new versions that are, in a sense, mutually exclusive:

None really lends itself to comparison with the others because each uses different tools for the task. On Columbia, Glenn Gould-accompanying Jaime La redo-employs a piano and dismisses the need for the gamba (a "superfluous" requirement in any case, the Columbia annotator assures us). On Orion, Endre Granat and Edith Kilbuck stick to the harpsichord but also reject the services of a gamba. On Tele funken (a set issued as Vol. 1 of Bach's chamber mu sic), Alice and Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Herbert Tachezi include a gamba and also announce that they are using "original instruments"-which, since their harpsichord was built in 1973, must mean that in addition to seventeenth-century violin and gamba, the violin bow as well as the gamba bow is a curved one. That, at any rate, is the way it sounds, though no indication is given in the album notes.

Let me say at the outset that I would throw out of court any version of these works that does not include the gamba-an essential component not merely in terms of color, which is important enough, but also in terms of line: There is too much of significance going on at the bottom of Bach's three-part writing to risk losing it when the texture gets thick overhead. With that proviso, let us step "out of court" for a moment and consider the two no-gamba versions.

Laredo and Gould provide a very strange experience indeed, one that at times seems so far removed from Bach that one literally squints at the score to see if the ears deceive. Gould seems to be pristinely bent on making the piano sound like the harpsichord it ought to be, and his solution is a jabbing staccato in all those left-hand even-sixteenth-note figurations that punctures the fabric of the music like so many bullet holes. In the fast movements this is less notice able, but in the adagios it is bizarre. Laredo's sweet violin sings its song benignly, but he sounds almost like a stranger who has wandered into the wrong room.

Gould's dominant presence also expresses itself in great freedom in embellishment, in which he indulges more liberally than any of the other keyboard players under consideration. At times this seems acceptable but not necessary, as in the opening measures of the first movement of Sonata No. 2, where he fills in elaborately around a dotted half note (the harpsichordists on other discs simply sustain it unadorned); at times it is incredibly distorting, as in the opening movement of Sonata No. 3, where a lavish series of upward-sweeping arpeggios dispels any semblance of the basic sixteenth-note pacing and creates a kind of rumba rhythm that must have the Kapellmeister spinning in his grave. These chords are arpeggiated by other performers but in a much tighter formation.

Well, there is no need to belabor the point. A musician of Gould's caliber does not fall into things of this kind idly, and one can only conclude that he must have something in mind that one fails to understand.

When he is unencumbered by the necessity of creating a unified ensemble sound and is free to go it alone, as in the Adagio for solo keyboard in Sonata No. 6, he is firm and clear in delineation of line and succeeds in turning the piano into a reasonably Bachian instrument.

The Granat/Kilbuck set falls into the general category to which I assigned the Melkus/Dreyfus al bum-straightforward, competent, not exceptional.

In violinistic terms Granat's playing is less polished and less nuanced than Laredo's, and he sometimes fails to hold a melodic line together so cohesively. In short, the tendency here is toward the dry side, in concept and execution. (It should be noted that the Orion set includes, in addition to the standard S. 1014-19 Sonatas, four alternate movements for those works and two more sonatas, S.1021 and 1023, for violin and continuo.) The Harnoncourt/Tachezi version, complete with viola da gamba, is something else again-an unusual exposition of these sonatas that takes a little getting used to but yields bright rewards in liveliness, in a sense of unfailing forward flow, and in rhythmic zest. The effect of the curved bow, which lacks bite on the downstroke attack of a note and lets the full sound swell in the middle, gives a quite different color to the proceedings, one which grows more at tractive as the ear adjusts to it. Harnoncourt/Tachezi are also believers in the baroque practice of playing some patterns of equal notes as if they were un equal-as in the first and third movements of Sonata No. 1. I have some reservations about the stylistic appropriateness with which Alice Harnoncourt conceives of certain note-groups, pressing ahead to the climactic note in a somewhat rhapsodic manner and underemphasizing the notes along the way; Men uhin, for one, pays more deliberate attention to each note in the pattern. But the Harnoncourt way, unde niably, creates momentum and vitality and, to my ear, produces one of the most interesting versions of these works on the market.

BACH: Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord (6), S. 1014-19. Jaime Laredo, violin; Glenn Gould, piano. [Andrew Kazdin, prod.] COLUMBIA M2 34226, $13.98 (two discs, manual sequence). Sonatas: No. 1, in B minor; No. 2, in A; No. 3, in E; No. 4, in C minor; No. 5, in F minor; No. 6, in G.

BACH: Works for Violin and Harpsichord. Endre Granat, violin; Edith Kilbuck, harpsichord. [Giveon Cornfield, prod.] ORION ORS 76213/5, $13.96 (three discs). Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord (6), S. 1014-19 (plus four alternate movements). Sonatas for Violin and Continuo: in G, S. 1021; in E minor, S. 1023.

BACH: Chamber Music, Vol. 1: Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord (6), S. 1014-19. Alice Harnoncourt, violin; Herbert Tachezi, harpsichord; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, viola da gamba.

TELEFUNKEN 26.35310, $15.96 (two discs, manual sequence).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Wagner's Roman Colossus

Rienzi enters the catalog in a performance that suggests the potential of Wagner's foray into Paris-style Grand Opera.

by David Hamilton

Rienzi was Wagner's first big success. By the time it was staged, in Dresden on October 20, 1842, he had already moved on to other things: Der fliegende Hollander was completed, and the foundations of the Tannhauser libretto laid out. But Rienzi's acclaim led directly to the presentation of Hollander in Dresden the following January, and to Wagner's appointment a month later as Kapellmeister to the Royal Saxon Court. For a short while, everything seemed possible; it was a turning point in the composer's career-one that stubbornly refused, however, to turn the way he wanted it to, for the Dresden audience didn't take to Hollander, nor later to Tannhtiuser, and the frustrations of the job eventually led to Wagner's participation in the abortive 1848 rebellion and his subsequent long exile from Germany.

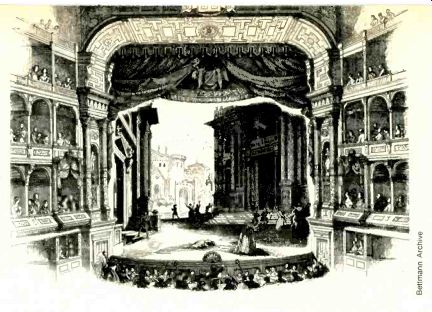

---- An old line cut shows the last scene of the fourth act

of Rienzi in progress during the work's premiere at the Konigliches Hoftheater

in Dresden.

Even Rienzi only made its way slowly beyond Dresden-a fact that is no reflection on its original success; censorship (revolution was a touchy subject in those days, as was the political role of the papacy), length, requirements of stage spectacle, and the demands of the title role all conspired against it. Eventually, of course, Wagner's later works stole the limelight, and Rienzi, along with most of the essentially Parisian tradition to which it belongs, passed into theatrical limbo, despite occasional revivals in Germany and Italy. By the time this review appears, a production will have taken place in San Antonio but prior to that Rienzi hadn't been heard in America since 1923, when a touring German company put it on in New York.

Now Rienzi joins such fabled works as Rossini's Guillaume Tell and Meyerbeer's Le Prophete [subject of a review on page 87-Ed.] and Les Huguenots in the phonograph's repertory of Grand Opera. The reasons for its early favor are not hard to discern. The music fairly bursts with energy, and it never lets up. Much of it is four-square, in the manner that Wagner didn't really beging to shake until after Lohengrin. Much of it is conventional, leaning heavily on diminished-seventh chords, string tremolos, and other stock devices of Romantic opera's lingua franca. Much of it is deriva tive, not only of the Parisian models, but also occasionally of Beethoven's Fidelio, of Mendelssohn and Schumann (the solo Messenger of Peace), of Bellini (Adriano and Irene frequently course in thirds and sixths). Some of it is inevitably tedious on records, without the visual spectacles that the repetitive mu sic was intended to accompany.

The substance of Rienzi is rhetoric and show, grand effects deployed on a grand scale. The libretto is laid out, not to present a character study of a fourteenth-century Roman visionary who sought to restore the city's great past, but to "wow" the audience with unexpected thrills, dazzling stage spectacles, and heroic vocal displays. Bulwer-Lytton's novel (not to mention historical fact) is drastically simplified, and even the principal characters are but stock figures: Rienzi the heroic champion of the people, Irene his faithful sister, Adriano Colonna the young man torn between duty to his father and love for Irene.

Through the five acts, they march in and out, responding predictably to the seesawing turns of the plot, hardly ever revealing any inner life. The subsidiary figures are totally indistinguishable, mere step-outs from the chorus. The whole thing is basically a machine to generate situations: marches and battles, proclamations and celebrations, interruptions and confrontations, benedictions and maledictions, an enormous and tedious ballet, and just about any thing else you can think of, up to the burning of the capitol with Rienzi and Irene inside it.

And yet it works, it moves along with drive and exuberance. For all that Rienzi isn't an opera I'd want to hear often, a really slap-up performance in the theater ought to be one hell of a show. Our chances of seeing such a performance are slim enough: It would be hard to cast (how about Janet Baker as Adriano, for starters?), a real challenge to keep rhythmically vital James Levine could do it), and al most prohibitively expensive to produce in proper grand style-strictly a festival proposition. Which is perhaps a roundabout way of coming to this point:

Don't let what you hear of Rienzi in this recording lead you to underestimate its potential impact or its role in Wagner's development. (He never wrote an other such work, but the Grand-Opera techniques are an essential element in later works, from Tannhauser to Parsifal.) The first of my reservations about the new recording concerns completeness; although the historical essay in Angel's booklet mentions the cutting that Wagner undertook before and after the premiere, it makes no statement about the version recorded.

Rienzi is a long opera, and Wagner enthusiastically acceded to abridgements for practical reasons; a copy made under his supervision and sent to Ham burg for consideration omits somewhere between 15% and 20% of the original, and the first printed score of 1844 is still shorter. (These revisions entail not only cuts, but also rewriting and re-orchestration.) Logically, either of these versions is a candidate for recording; both of them can claim to come from the hand of the composer at a time when he was still involved in the work. Equally authentic, of course, would be Wagner's original full-length score-except that it hasn't been seen since 1945 (when it was the property of Adolf Hitler), and there is no other surviving source for the orchestration of certain pas sages. A new edition of the full score, now being published by Schott, will present all the relevant material, including the surviving vocal score of these passages. (By orchestrating them, Edward Downes and Ernest Warburton prepared the text for a BBC broadcast last summer that was probably even more complete than the Dresden premiere.)

But EMI didn't have access to all this material when its recording was made, so it settled for a simpler alternative: This recording corresponds (barring a few minor vocal variants and the omission of indicated literal repeats) to the Farstner edition of 1899 (published in miniature score by Eulenburg). Pre pared, it seems, by Cosima Wagner and the Bayreuth chorus master Julius Kniese (although no editorial credit appears on the title page), this edition is, at the very least, controversial-and in any case does not stem from Wagner himself. There isn't space here to explore this matter in any detail (and, until the new edition and its critical report are completely avail able, we won't know enough of the facts), but among its numerous omissions is one that is greatly to be deplored: a somber ensemble of lamentation in the third-act finale. True, Wagner himself cut this in later Dresden performances (much to the distress of Tichatschek, the original Rienzi, who admired it greatly)-but only for reasons of time, which should not have kept it out of the recording. There is nothing sacred (or "authentic") about the cuts Cosima and Kniese made long after Wagner's death, and it defies common sense to devote an entire side to some of history's more perfunctory ballet music (though not even all of that, in fact) while omitting this superb piece of concerted writing.

Not that this version of Rienzi is brief. It runs to 1,184 pages of miniature score, including passages probably not performed in many decades (recent stage productions have tended to omit nearly half the score); some of them are not even in the singular pirate set circulated a few years back, which spliced together material from six live-performance tapes in its search for completeness (including material not in the Angel set, notably the aforementioned third-act ensemble). Two recent European sets are put out of the running altogether: Top Classic's issue of a 1942 Berlin broadcast (H 657/8) and Eurodisc's publication of a 1974 Berlin concert performance of limited distinction (88 619 XDR). Two discs each, these could hardly be described as comprising more than "high lights." Not only is Angel's performance more complete than those, it is more listenable. Its besetting sin, to my ears, is that it sounds like a studio job, a reading rather than a "real performance." Heinrich Hollreiser is a perfunctory conductor, rarely investing Wagner's striding and soaring tunes with much lift (try the figure in the orchestra that enters with Cecco in the first-act finale, or the melody that opens the second act-they're just played, not characterized). It's all decent and orderly-the orchestra copes fairly well and the chorus bears up impressively under Wagner's extensive demands--but the vitality and variety of the score are muted.

Similar comments apply to the singing; even when technically satisfactory, much of it is on the neutral side. Despite his pronounced beat on sustained notes (and not only on high ones), Rene Kollo is a bearable Rienzi-and that's saying quite a lot, for the writing is murderous, rising constantly to high A flats and A's, much of it very exposed, declamatory stuff. With experience, I'm sure Kollo would find more variety in the part, rather than bulling his way through it at full tilt, which is wearing for us as well as for him. Only the circumstances of modern studio recording allow him to do it this way; for a stage performance he would have to learn how to save his strength, and that might force him to vary his approach-or risk instant suicide for a voice that even now shows signs of ill use and faulty technique.

The young Adriano is a travesty part; Wagner realized that next to Rienzi a second tenor would be impossible. Janis Martin is the most committed and in tense member of this cast, but her pitching is often unreliable. She's an elevated mezzo, and I've heard her sing soprano parts rather satisfactorily, so the inference I draw is that she didn't have time to work out all the problems in this elaborate, high-lying role (most mezzos take Adriano's aria down a tone or more, but she sings it as written). Siv Wennberg makes a potentially exciting sound, but the bulk of her work is marred by alarmingly poor intonation, perhaps for the same reasons. When these three principals join in a triple cadenza in the second-act finale, the effect is simply excruciating.

Except for Gunther Leib (Cecco), the various lower voices are passable, and Peter Schreier's Baroncelli is the most distinguished, distinctive piece of work in the whole set.

The sound is respectable enough, although the off stage material tends to sound boxy. Aside from a few patches of crowd noise, there's little effort at "production," and the sword-on-shield banging that Wagner scores into the coda of the Battle Hymn has simply been omitted. The ballet music, given a side to itself, is brought to a full close, spoiling the effect of the interrupting dissonance. which here lamely be gins the subsequent side. Another clumsy break comes on the brink of Adriano's aria.

Finally, on my copy of Side 8 (from a G3 stamper), the fourth act's final pages are chopped off in mid-phrase, twelve measures before the end. Presumably this will be corrected in due course; in the meantime, caveat emptor--i.e., check Side 8 before purchasing.

WAGNER: Rienzi. Irene Siv Wennberg (s) Adriano Colonna Janis Marto (s) Messenger of Peace Ingeborg Springer (s) Rienzi Rene Kona (t) Baroncelli Peter Schreier (t) Cecco del Vecchio Gunther Leib (b) Paolo Orsini Theo Adam (bs-b) Steffan Colonna Nikolaus Hulebrand (bs) Raimondo Siegfried Vogel (bs) Leipzig Radio Chorus, Dresden State Opera Chorus, Dresden State Orchestra, Heinrich Hollreiser, cond. [David Manley, prod.]

ANGEL SELX 3818, $35.98 (five SQ-encoded discs, automatic sequence).

----

The Corrected Rienzi

The Side 8 editing error noted by Mr. Hamilton has indeed been corrected, but not before first-production copies were shipped to dealers. (The review set was in fact store-bought.)

For those who find that they have bought un corrected copies, Angel promises to replace the disc containing Side 8. Write (a postcard will do) to the Consumer Relations Dept., Angel Records, 1750 N. Vine St., Los Angeles, CA, 90028.

----------------

-------------

(High Fidelity, March 1977)

Also see: