The New Releases

A Window on Lully's Operatic World

--- An artist's rendering of a typically spectacular operatic stage setting of Lully's time

---- Jean-Baptiste Lully--engraving by Edelinck

Columbia's recording of Alceste offers great music tied to the trappings of French classic theater.

by Paul Henry Lang

JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632-87), Florentine by birth but as French as escargots with garlic sauce, was one of the most formidable musical personalities in the history of music: head of Louis XIV's musical establishment, absolute ruler of opera in France, the first great conductor (inaugurating disciplined and well-rehearsed ensemble playing), an excellent violinist and founder of the French school of violin playing, an able actor and dancer, and a superbly gifted man of the theater who not only composed and conducted his operas, but was also his own competent stage di rector.

As a composer, he dominated the scene for a hundred years, founding French opera, reforming the ballet, creating the stately French overture and the orchestral suite, the latter eagerly adopted by all musicians, Bach and Handel included. His operas were immensely popular long after his death, and not only Rameau, but even Gluck, a century later, studied them and borrowed here and there.

Yet despite Lully's unprecedented fame, Columbia's new Alceste is the first integral recording of one of his operas. The reason for this curious situation is that, unlike Monteverdi's and Cavalli's even earlier operas, which can be revived successfully for twentieth-century audiences, Lully's pose too many grave problems.

His was the age of Corneille, Racine, and Moliere (all three of them at one time or another Lully's librettists, surely an honor no contemporary can boast), of the classical French theater, and of the supreme literary lawgiver, Boileau. No wonder that to the French, who always begin with literature, the libretto was what mattered most in an opera. They called their music drama "tragedy in music" or "lyric tragedy," not opera, and they expected the libretto to stand on its own as a play to be read.

Also, French opera having among its predecessors the court ballet, which they insisted on retaining in the music drama, the tragedie Iyrique was a sumptuous spectacle to which the French theatre a machines was well adapted. Rousseau, in his Dictionary of Music, says that "magic and the merveilleux be came the foundations of the lyric theater." Unfortunately, no modern theater can duplicate these splendors; of course we do not have a Sun King to foot the exorbitant expenses. It is clear, too, given the extra ordinary importance of the visual and the literary element in the tragedie Iyrique, that no recording could do justice to it.

Lully, a sharp observer and even sharper entrepreneur, studied the dramatic performances in the Comedie Frangaise and gave the French what they wanted: rhetorical recitation (he created the French recitative) of rolling alexandrines, the literary cothurnus of French drama, set to music in which every note and interval was adjusted with unexampled skill to the scansion and inflections of the French language. This narrative melody originated from the inner laws of the French language (Rousseau called it "discourse in music"); it is still alive in Pelleas et Masande. Unfortunately, it can become terribly boring, especially when the words are not those of a great dramatic poet. During the opera war in the next century the partisans of Italian opera called Lully's tragedies "a sort of psalmody." Lully's principal librettist, Philippe Quinault, slipped into the interregnum between Corneille's temporary retirement and Racine's appearance on the scene; he was a minor playwright but thoroughly indoctrinated in the French classical tradition.

Though both Boileau and Racine raked him mercilessly, he was greatly admired, even elected to the French Academy: to us, however, he is merely a manufacturer of correct alexandrines who butchered Euripides' great drama.

His little lyrics for solos, duets, and trios are not bad, and it is here, in these little ariettes, that Lully's music instantly picks up and becomes attractive to us. There are some fine dramatic scenes in Alceste, a great deal of delectable dance music, and many superbly set choruses; Lully may be a little frosty and precious, but he was a great composer.

The long orations, the exaggeratedly formal, pathetic rhetoric of the French national drama, are exacerbated by the profusion of appoggiaturas on which conductor Jean-Claude Malgoire seems to insist, making every little sentence full of soupirs, a mannerism that after a while becomes trying. The twenty-one (!) roles are sung by ten singers, a practice that, though sanctioned by seventeenth-century us age, only contributes to a lack of individual characterizations; in a recording without the visual aid of the stage, it nullifies what little action there is in the drama. The employment of a wind machine and other stage noises adds very little to the scenic feeling.

The singing is generally good. Of the large cast, I should single out soprano Renee Auphan (who takes four roles) and baritone Max van Egmond (two roles); the latter enunciates French beautifully though he is a Dutchman. The chorus is superb, exquisitely balanced, and very well recorded, but the orchestra is mediocre; the overture is a bit messy, and some of Lully's charming vignettes, the ritornels, especially those after the choral numbers, are moribund. Malgoire's rhythm is soft, and his sense of drama and color seem somewhat limited; there is more life in this music than he finds in it.

Malgoire's article in the accompanying booklet (which is not a specimen of the printer's art) is rather unsatisfactory; neither his commentary nor that of Francois Lesure, a distinguished scholar, is well served by the anonymous translator-this sort of near-fractured English is embarrassing. All in all, however, we should be thankful that this landmark opera is finally available, for there is much admirable music in it.

LULLY: Alceste. Alceste Felicity Palmer (s) Nymphe de la Seine, Thetis. An Afflicted Woman. Diane Renee Auphan (s) Gloire. Cephtse Anne-Marie Rodde (s) Nymphes des Thufferies, de la Marne. de la Mer. Proserpine Sonia Nigoghossian (s) Admete Bruce Brewer (t) Lychas, Apollon. Alecton John Elwes (t) Pheres, An Afflicted Man, Pluton Pierre-Yves Le Maigat (b) Alcides Eole Max van Egmond (bs-b) Straton Marc Vento(bs) Licomede. Cleante. Charon Francois Loup (bs) Maitrise Nationale d'Enfants, Raphael Passaquet Vocal Ensemble, Grande Ecurie et Chambre du Roy, Jean-Claude Mal goire, cond. COLUMBIA M3 34580, $23.98 (three discs, automatic sequence).

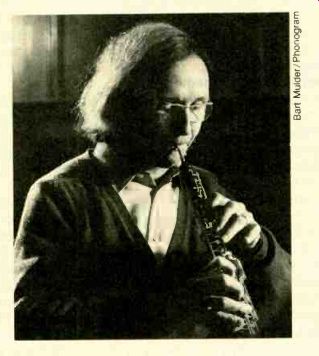

Heinz Holliger: Now That's Charisma

The Swiss oboist's latest Philips disc as usual blends dazzling virtuosity with irresistible personal magnetism.

by R. D. Darrell

A RARE BIRD indeed is the instrumentalist who com bines technical near-perfection with distinctively individual appeal-the mysterious but irresistible magnetism for which the often misused term "charisma" for once applies exactly. The only current one I'm sure about is the extraordinary, not-yet-forty Swiss oboist Heinz Holliger. Everything I have heard from him comes as close as humanly possible to my aesthetic as well as technical ideals, and the present program--deftly accompanied and beautifully re corded (not too closely, but with grippingly vivid presence)--again offers oboe playing and musicianship at its finest. It also represents musicassette as well as disc processing at their current best.

Only the Bellini E flat Concerto, a diverting little curio, is familiar, at least to specialists; Holliger him self has recorded it twice before (for Monitor and Deutsche Grammophon), but those versions date back more than a decade. The other three works are, as best I can tell, recorded firsts, at least on this side of the Atlantic. For that matter, I've never before en countered anything by one (Bernhard Molique) of these three German composers, all of whom are roughly contemporary with Mendelssohn, are more or less influenced by him, and generally share his more classical than Romantic aesthetic orientation.

Moscheles' F major Concertante of 1830, probably inspired by the flute/oboe duo-concerto by his teacher, Salieri, is lightweight but disarmingly lilting when played as well as it is here with Holliger's virile lyricism happily married to the feminine grace of Aurele Nicolet's elegant fluting. The G minor Con certino by the now-forgotten Molique (1802-69) be trays the influence not only of Spohr, but also of Mendelssohn and Beethoven. What gives it distinction is its dreamy Adagio, with a heart-twistingly poignant solo part that might have been written with Holliger's artistry in mind. Yet for me the prime discovery here is the relatively short but prodigally varied F minor Konzertstiick by Julius Rietz (1812-77), with its haunting first-movement arioso, infectiously zestful intermezzo, and vivaciously bravura finale.

There is far more in the music here, to say nothing of the incomparable solo performances, than war rants restriction to specialists' ears and libraries only.

H. Holliger AND Aurile Nicolete---Orchestral Works with Oboe and Flute. Heinz Holliger, oboe: Aurele Nicolet, flute; Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, Eliahu Inbal, cond. PHILIPS 9500 070, $7.98. Tape: 00 7300 515, $7.95.

Bellini: Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra, in E flat. Molique: Concertino for Oboe and Orchestra, in G minor. Moscheles: Concertante for Flute. Oboe, and Orchestra, in F. Rietz: Konzertstuck tor Oboe and Orchestra, in F minor, Op. 33.

==============

(High Fidelity, Oct. 1977)

Also see: