One of America's most quotable composers discusses himself and his music, and our reporter assesses the recordings.

by Allan Kozinn

---Samuel Barber, in one of his last photographs

"I think I'm a country person. Most everything I've composed, I've composed in the country, and the pieces I've written in the city have generally been started in the country. I'm sure you've noticed that I haven't been notably productive since I moved to New York. Like Messiaen, I like birds. And I need the absolute silence of the country.

I need places to walk. Now I can walk through Central Park, but it isn't the same. I've tried to analyze it, but to my mind, it's just not as satisfying. It isn't really natural woods." The speaker was Samuel Barber, one of the most celebrated composers this country has produced. Like Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Elliott Carter, William Schuman, and others of that golden generation that came to prominence during the first three decades of this century, Barber was intent on showing the world that serious composition was not an exclusively European art form. He also firmly believed that new music need not be forbidding, and by writing in a Romantic, accessible idiom, he built a large international audience for his own work and for American music in general.

Barber died of cancer on January 23, a little more than a month before his seventy-first birthday. The comments about city life's dearth of inspiring charms, as well as those that follow, were part of what turned out to be his last formal interview, granted in December 1979. He had by then composed all he was destined to, although he maintained that he would be writing again as soon as he found a way of keeping the intrusive city noise out of his workroom.

The day of the interview, in fact, he had a team of workmen building soundproof walls in his Fifth Avenue apartment, one of several attempts to solve this problem.

Of course, the increasing severity of Barber's illness-which he would not publicly admit was anything serious--took at least as great a toll on his composing as did the lack of country quiet. As he pointed out, his output had indeed been slim in recent years: There were the Three Songs, Op. 45, in 1974; the revision of his second opera, Antony and Cleopatra, in 1975; the short Ballade for solo piano in 1977; and the Third Essay for Orchestra in 1978. The New York Philharmonic, which gave the Third Essay its premiere, had also commissioned an oboe concerto, scheduled for early 1979, but Barber laid this work aside after completing only one movement.

According to an early biography, Nathan Broder's Samuel Barber (G. Schirmer, 1954; out of print), the composer was shy, withdrawn, and moody as a young man; those traits endured, and perhaps intensified, as he grew older. He was, I was told before meeting him, "absolutely brilliant and funny as hell-but an impossible man." I was also told that he did not enjoy long conversations with strangers, particularly journalists. He had, therefore, originally canceled our interview, as well as most of his other appointments, and, was refusing at the time to see anyone but his closest friends. It was one of the latter, pianist and composer Phillip Ramey, who persuaded Barber to keep our appointment.

And so, on a brisk, cloudy morning, Barber turned up at the offices of his publisher, G. Schirmer, looking healthy and apparently in good spirits. He answered questions for about an hour and a half, and then, as we parted, he asked, "What do you think-did I give you any good lines?" If there was one thing the interview had plenty of, it was good lines.

Barber was clearly not given to lengthy and serious rhetorical pronouncements about the meaning and purpose of music; nor was he interested in predicting where current compositional trends might lead. He refused to speak analytically about his music or his style, and when he discussed his work at all, it was in general and usually anecdotal terms.

Otherwise, he seemed happy to sit back and play the role of the cantankerous elder statesman, musing pointedly about the music world's shortcomings.

I reminded him, for instance, of a statement he had made to MUSICAL AMERICA in 1935, when he won his first Pulitzer traveling scholarship. "The present offers fine opportunities for young composers," the twenty–five-year-old Barber had said. "The public seems ready to encourage native talent, and if composers are ready to do their part and offer something worthwhile, American music may surely be expected to make great progress." What, I wondered, did Barber think of the prospects for young composers in the 1980s? "Oh, I think it's much harder. First of all, there were conductors who were interested in American music in those days. Koussevitzky, for example. When young conductors tell me they have trouble putting together interesting programs, I tell them to look at the Koussevitzky/Boston Symphony programs. They were superb-much better than Toscanini's. They had the classics, the Romantics, and almost every program had an American work. He was very enthusiastic about American music, and he played it beautifully. For a composer, it all hinges on enthusiastic conductors. But that's all gone now. Why? Well, don't ask me-why don't you go ask Mr. Muti? He came here to take a nice American post and announced in a New York Times interview that he's never conducted an American work in his life.

Well, that's the end of us in Philadelphia. My hometown. Will he come around once he's on the Philadelphia podium? I rather doubt it. It seems many of today's young conductors are too lazy to learn new things. And it's net only laziness: They are not at all convinced that new music is any good. Therefore, new works only get done when the wives of the composers pressure the members of an orchestra's board to have certain works played. That's why I think all composers should get married as early as possible."

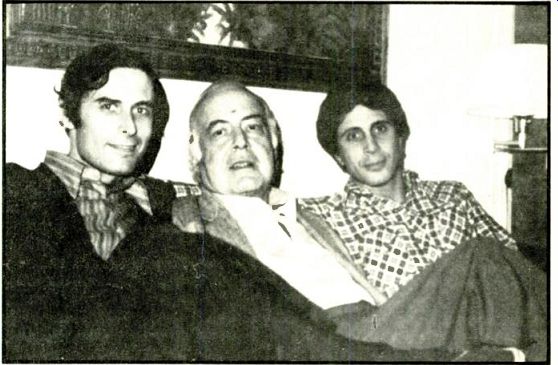

---- Barber at home, Flanked by friends Phillip Ramey and John Corigliano,

American composers of the subsequent generation

Barber himself never married, but his music has found plenty of champions. Virtually from the start, it brought him the popular and financial success that allowed him to forgo academic and other extra-compositional occupations.

In 1928, at eighteen, he entered a violin sonata (unpublished) in a composition contest and won the first of several substantial prizes and grants that put him in the enviable position of being able to spend every summer from his late teens through his late twenties touring Europe and composing. The Philadelphia Orchestra performed his first orchestral score, The School for Scandal Overture, when he was twenty-three, and two years later, in 1935, his Music for a Scene from Shelley was performed by the New York Philharmonic. The same year Barber won the Prix de Rome and made his recording debut as both composer and baritone, singing his Dover Beach for the Victor microphones. In 1937, Artur Rodziski gave the American premiere of the First Symphony with the Cleveland Orchestra, repeating it that summer in Salzburg. And in 1938, Arturo Toscanini added his seal of approval, leading the NBC Symphony Orchestra in the first performances of the First Essay and the work that became not only Barber's best-known score, but one of the most frequently played of all twentieth-century orchestral works, the Adagio for Strings.

The urge to compose hit Barber early. He was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1910, took his first piano lessons when he was six, and began composing at seven. Evidently without much encouragement, his compositional drive flowered quietly until, at age nine, he left his mother a letter that read, "I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now don't cry when you read it because it is neither yours or my fault [sic]. I suppose I have to tell it now without any nonsense. To begin with, I was not meant to be an athleit [sic]. I was meant to be a composer, and will be I'm sure. Don't ask me to try to forget this unpleasant thing and go play football--Please--Sometimes I've been worrying about this so much it makes me mad (not very)."

A closet composer no more, Barber continued his musical studies on his own, attempting an opera when he was ten (called The Rose Tree, to a libretto by the family cook). In 1924, the Curtis Institute was founded, and Barber, then fourteen, went to Philadelphia as one of the conservatory's 357 charter students to study piano, voice, and composition.

There in 1928, he met another composition student, Gian Carlo Menotti, and the two entered upon a lifelong friendship. They traveled around Europe together through the 1930s and eventually (from 1943 to 1974) shared a large woodland estate, called Capricorn, near Mount Kisco, New York. Many of Barber's finest scores were composed in the countrified seclusion of Capricorn, and it was there that he and Menotti collaborated on a couple of stage-works (Menotti supplying the librettos): Barber's first opera, Vanessa (1957), and a ten-minute "chamber opera," A Hand 'of Bridge (1959).

In January 1934, in Vienna, Barber made his debut as a conductor, a sideline he gave up happily in the early 1950s, soon after making a short series of "Barber Conducts Barber" recordings. Why did he stop? "Because on-stage I had about as much projection as a baby skunk. Projection, nerves-and I got bored of rehearsing my own music.

Some composers just adore it, but I don't find it very interesting. There's a lack, in me, of pedagogical talent. And when you're guest-conducting, either you have to have that talent or else you have to have an authority over the orchestra to make them do it right. Guest conductors rarely have that authority, whereas if it's your own orchestra, you can just do what Toscanini did: You can scream, 'Stupid’! Imbecile!', and throw down your watch.

I've seen him do that. But he was Toscanini, and it was his orchestra; they wouldn't dare make the mistakes with him that they did with me.

"Oh, I suppose there's something to be gained from hearing a composer conduct his own work. My tempos could be definitive. But generally, I don't believe composers make very good conductors. Someone who conducts every day can give a technically superior performance. I remember the last work of mine I conducted: my Second Symphony with the Boston Symphony. Not a bad way to end a conducting career. But by the time I got to Boston, I'd conducted it in Denmark and in England, and I knew exactly where the violas were going to he wrong, and where I'd have to make them do it over and over, very slowly. Now how can you remain interested in doing that, whether it's your own music or not?"

Not the gregarious type, Barber was a less vociferous public campaigner for the cause of new American music than Copland, Schuman, and Leonard Bernstein have been. However, he did occasionally take a stand, serving briefly as president of the International Music Council of UNESCO and, in 1952, joining a group of his fellow composers in a successful campaign to win a larger allotment of royalties for serious composers from ASCAI'. Now and then, even came up with a plan to encourage younger composers. One such scheme involved the commission for Summer Music (1956), by the Chamber Music Society of Detroit. He had agreed to set aside his usual fee, accepting instead the proceeds of a "pay what you can" collection among the audience, most of the contributions falling between $1.00 and $5.00.

----- Composer Aaron Copland in discussion with Barber, in a photo by

Ramey

"The idea," he recalled, "was that, if this caught on, music societies around the country would take up similar collections and use the funds to commission young local composers who needed experience and exposure. I made a speech against myself, essentially, telling them it was crazy that they didn't use local composers. It was certainly done in Bach's day. But they didn't like that idea.

They just wanted the same tired old names--Copland, Sessions, Harris, me--so it never got off the ground. Consequently, not only are young composers still not getting the commissions, but the prices for new works are staying rather high. In fact, I've done my best to increase them. Which I guess ruins my story." He was able to increase those fees-to a level that was reportedly the highest in the country-primarily because he was able to produce music that audiences consistently enjoyed. His conception of the ideal American idiom differed considerably from those of his peers, and he seems not to have been touched by the need to keep up with experimental and stylistic trends. In the 1940s, when the predominant American style emphasized the rediscovery of nationalistic musical roots, Barber's major works-the Violin Concerto (1939-40), the Second Essay (1942), the Capricorn Concerto (1944), and the Cello Concerto (1945)-reflected an impulse to continue developing in his own direction rather than turn to folk tunes for raw material.

When the compositional world dove headlong into atonality, serial ism, and a host of other experimental, intellectual forms in the 1950s and '60s, he proceeded along his own lyrical and often intensely subjective path, veering moderately toward a more chromatic, angular, and dramatic language.

Thomson, in his hook American Music since 1910, calls Barber "a reactionary," and that may be. He was not, certainly, the kind of composer we would call a daring trailblazer; yet the widespread impression that all his music aspires to the simplicity of the Adagio for Strings is quite wide of the mark. Of course, his conservatism may be vindicated by the fact that many composers in the two succeeding generations have opted to follow in his neo-Romantic footsteps, some with a good deal of popular, commercial, and even critical success. All the same, one can't help but wonder how Barber was able to witness the intense swirling of styles, forms, and media of the last fifty years without being tempted-as were Stravinsky and Copland-to dabble on the experimental fringes. So I asked him.

"He was Toscanini, and it was his orchestra; they wouldn't dare make the mistakes with him that they did with me." "Ah, I was waiting for this," he replied. "Why haven't I changed? Why should I? There's no reason music should be difficult for an audience to understand, is there? Not that I necessarily address the audience when I compose or, for that matter, the players. Or posterity. I write for the present, and I write for myself. Myself and Helen 'Mrs. Elliott’ Carter. Why Helen Carter? Well, she's the judge. She announced once that all American composers are dead except for Elliott, so we have to take our music to her, and she tells us what to do.

"I think that most music that is really good will be appreciated by the audience, ultimately. I can't say I listen to much new music now, though. I know a few names, I've heard a few recordings; but no, I don't want to suggest which of today's composers will be the big names of the future. I'm not a necromancer, you know. Anyway, this is a question for the musicologists. They know everything."" The Recordings "The recording situation is miserable and getting worse," Barber observed.

"I wish--I think all composers wish--that a certain amount of money could be put aside by foundations for the recording of good first performances of new works. And then those recordings should be distributed well--not just to schools and libraries.

That's not enough. That specialty approach doesn't give the music any exposure. They should be distributed by the major companies, so that people can find them and hear them and so that young musicians can listen to them and decide whether they want to perform the music themselves. There are a lot of things that might be changed in the musical world, if we got down to the nitty-gritty." There are indeed, and Barber's wish seems more remote all the time. But in truth, he could not justifiably complain about his own representation on discs. Of his forty-seven works with opus numbers (some of which he withdrew in fits of self-criticism) and his handful of unnumbered scores, virtually all have been recorded at least once.

The following discography is arranged chronologically within genres, except for the vocal music, where couplings suggested a different approach. Details of the recordings discussed are listed at the end of each section. Where discs contain works by other composers, evaluations are confined to those of Barber.

Orchestral works

The Serenade, Op. 1 (1929), might appropriately have been grouped with the chamber works, since it is designated "for string quartet or string orchestra"; yet all the available recordings present it in its orchestral guise. It is a vibrant neoclassical work in three movements, the last a spirited dance. Vladimir Golschmann and the Symphony of the Air give a thoroughly respectable reading on an all-Barber disc (Vanguard VSD 2083), but the version by Gerard Schwarz and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra (Nonesuch D 79002) is slightly preferable for its more exciting pacing, more sensitive balancing of the string lines, and (digital) sonic transparency. Both accounts move rather quickly, emphasizing the agitation and energy in the score. Nicolas Flagello and the Rome Chamber Orchestra (Peters International PLE 059) take a slower, broader approach, sacrificing vigor in favor of a somewhat exaggerated elegance.

The School for Scandal Overture, Op. 5 (1931), and Music for a Scene from Shelley, Op. 7 (1933), were composed during two of Barber's summer sojourns in Italy and were both inspired by literary works-the overture by Sheridan's eighteenth-century farce, Shelley by Prometheus Unbound, Act II, Scene 5. The overture is the more gripping piece, its insistent tempos and brash, tonally disoriented sections contrasting with moments of quiet, pastoral D major melody, all packed into about seven and a half minutes. Barber was intent on showing his mastery of orchestral hues in this early work, and the brilliance with which he succeeded is best heard on an excellent, budget-priced all-Barber LP by Thomas Schippers and the New York Philharmonic (Odyssey Y 33230). The Howard Hanson/ Eastman-Rochester recording, at mid price (Mercury SRI 75012), is an earnest yet unfocused reading-no real alternative. Shelley is more subdued, both orchestrationally and thematically, and certainly the most introspective and mysterious of Barber's early scores. There are two excellent recordings available: a smooth reading by Golschmann (Vanguard) and a marginally crisper one by David Measham and the West Australian Symphony (Unicorn UNS 256). "Sometimes I get tired of hearing the Adagio for Strings. But I amuse myself during performances because I know there's going to be a mistake somewhere.

Happens every time." Thomson may have had Barber's First Symphony, Op. 9 (1935-36), in mind when he labeled him a reactionary. The only hint that the work was composed in this century is its theme-pure Puccini.

Touches of Tchaikovsky shine through, too, with nothing to suggest that this is the work of an American. To some listeners, all this may sound appealing, and the work is attractive, impassioned in places, and finely crafted throughout. Hanson (Mercury SRI 75012) is sympathetic, but his orchestra plays messily. Much better are the more accurate and incisive Kenneth Schermerhorn/Milwaukee Symphony (Turnabout TVS 34564) and Measham /London Symphony (Unicorn RHS 342) readings.

"Sometimes I get tired of hearing the Adagio for Strings," said Barber about his most famous work, which first appeared as the second movement of the String Quartet, Op. 11 (1936). "But I amuse myself during performances, because I know there's going to be a mistake somewhere; I just wait for it to happen. It's such an easy work, they never bother rehearsing it. And orchestra psychology is rather funny: When they see whole notes, they think, 'Oh, we don't have to watch the conductor.' Invariably, a viola or a second violin will make a mistake.

Happens every time." Splicing technique has shielded us from those errors, by and large, yet the variety of interpretive approaches to this simple work is incredible: If you want merely a facile lushness, you can't go wrong with Eugene Ormandy/Philadelphia (CBS MS 6224). Bernstein, too, basks in a thick string sound, but he takes the work at a snail's pace, leading the New York Philharmonic through a flabby, distended performance (CBS M 30573).

I Musici (Philips Festivo 6570 181) takes it at a more sensible clip, but the string playing is unconscionably rough. The Neville Marriner/Academy version (Argo ZRG 845) is thoughtful and well paced, beginning soft and slow, steadily building in intensity. If you can find it, the historic Toscanini/NBC Symphony rendering from 1942 (RCA I.M 7032) is a gem in every sense; of the available recordings, the Charles Munch/Boston (RCA AGL 1-3790) comes closest both to Toscanini's velvety, flawless string tone and to his brisk, no-nonsense tempo. A sterling Adagio in an all-Barber setting is the Schippers on Odyssey.

The Essays No. 1, Op. 12 (1937), and No. 2, Op. 17 (1942), are among Barber's most immediately engaging scores. Aptly titled explorations of orchestral sonorities, each grows from the simplest kernel of musical thought and moves from a somber, questioning mood through a contrapuntally playful one to a resounding full orchestra climax. The only available recording of the First Essay is the Measham /London Symphony (Unicorn RHS 342), a tight reading that, unfortunately, is not equaled by the performance of the Second Essay on the same disc. Here, Mea sham's detail work-for instance, his emphasis of the woodwind triplets accompanying the melodic exchange between the violas and oboes early on-is often insightful, yet the performance is marred by some awkwardly broad tempos.

The Schippers (Odyssey) is better, if not as sharply detailed, but there is a recording flaw (oxide dropout?) at the climactic Iii, tranquillo. Thus, the best representation of the work is Golschmann's quick-moving, finely detailed performance (Vanguard), almost Wagnerian in scope and well recorded.

Between the two Essays came the Violin Concerto, Op. 14 (1939-40), a work that gave Barber a good deal of trouble. It was commissioned by a soap manufacturer for a young violinist who complained first that the opening two movements were not sufficiently showy, and later that the perpetual motion finale was unplayable. It's playable, of course, and the work as a whole is drenched in a sugary romanticism that certainly supports an emphasis on sweetness of tone, as in the Ronald Thomas/Measham recording (Unicorn UNS 2561. But Isaac Stern's more biting, virtuosic rendering is more to the point. He digs solidly into the strings yet conveys tonal warmth; his passagework is cleaner and more logically phrased; and he benefits from a sharply etched orchestral accompaniment from Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic (CBS MS 6713). From 1943 to 1945, Barber was an Air Force corporal, and he dutifully devoted some of his musical energies to the war effort. The Commando March (1Q43) is a superfluous patriotic foot-lifter, hardly worth bothering with. But if you must, at least go for the bright, brassy sonics of the Frederick Fennell/Cleveland Symphonic Winds digital version (Telarc DG 10043). Barber's other wartime effort is the Second Symphony, Op. 19 (1044). The Air Force commissioned this work, allowed him to work on it at Capricorn, and even flew him from one air base to another so he could gather atmosphere. With greater reliance on dissonance and modernistic rhythmic irregularity than any previous Barber score, the work seemed to signal a new direction. In the early 10'Oc, though, Barber withdrew the symphony, saying only that "it wasn't very good." From the recording he made with the New Symphony Orchestra of London, in 1950 (Everest 3282), it's easy to see why: Although it has its thrilling moments and is, for Barber, adventurous, it's too densely packed and lacks cohesiveness. He discarded the outer movements and published a revised Andante, called Night Flight, Op. 190. The Meacham/London Symphony recording (Unicorn RHS 342) conveys the night flyer's loneliness that informs this bleak tone painting.

Overt lyricism returns in the Capricorn Conc., for flute, oboe, trumpet, and strings, Op. 21 (1944), and the Cello Concerto, Op. 22 (1045), a pair of works that mix the rhythmic and harmonic simplicity of the violin concerto with touches of the Second Symphony's more sophisticated jaggedness. Capricorn is a light-textured work, full of an almost tactile weaving of string and solo instrument lines and containing a few passing nods to Copland's works of the same period, particularly in the last movement. The Hanson recording (Mercury SRI 7504°) serves the score well, hut surely it's time for an alternative release of this delightful work.

The cello concerto, a deeper, more trenchant composition, is available in two authoritative if aging versions-the 1966 recording by the cellist who gave the work its premiere, Raya Garhousoya, with Frederic Waldman and Musica Aeterna (Varese Sarabande VCS 81057), and Zara Nelsova's 1050 disc, with Barber conducting (Decca Eclipse import FCC 707). Barber gave most of his attention in the 1950s to stage works, and when he returned to orchestral writing with the Toccata festiva, Op. 36, and Die Natali, Op. 37 (both 1060), it was with a new outlook. Toccata festiva is a single-movement organ concerto, surging with energy and richly chromatic: the highlight is a tough cadenza for pedals alone. Although the recorded sound of the F Power Biggs/Ormandy recording (CBS MS 6308) is rather dry, the playing is first-rate (and there are no alternatives). Die Natali, on the other hand, is an extended fantasy on Christmas carols and therefore aspires to a certain festive charm. But given the subject matter, the dense scoring seems heavy-handed, and the work, recorded by Jorge Mester and the Louisville Orchestra (Louisville LS 745) is one of Barber's least satisfying.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning Piano Concerto, Op. 38 (1962), shows Barber again in top form. The piano writing in the fast movements is spectacular, and the orchestral accompaniment is often hard-driving, incisive, and brilliantly hued, its acridity set off by stretches of melodic beauty.

John Browning gave the premiere performance, and he had the work solidly in his fingers by the time he recorded it, with George Snell in 1°64-a performance (CBS MS 6638) yet unequaled on disc. The budget price of the competing version by Abbott Ruskin and David Epstein (Turnabout QTVS 34683) may he tempting, but the distantly miked, overly ambient sound is horrid. The Browning/Szell is well worth the difference in price, and if you seek out the British import version (CBS 61621), you can get it coupled with the Stern/Bernstein recording of the violin concerto.

Barber's last finished work was the Third Essay, Op. 47 (1078); it begins with some strong, colorful ideas but soon loses energy and direction, leaving its promise unfulfilled. Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic give a good account of the work (New World NW 300). Of Barber's orchestral works, only the Fadograph of a Yestern Scene, Op. 44 (1071), and the Canzonetta movement (1078) from the unfinished oboe concerto have not been recorded.

In the list that follows, performing groups are indicated with appropriate combinations of P (Philharmonic), S (Symphony), C (Chamber), and O (Orchestra). Where a set includes more than one disc, the number is given parenthetically following the record number.)

VANGUARD VSD 2083-Serenade, Op. 1; Music for a Scene from Shelley, Op. 7; Essay for Orchestra, No. 2, Op. 17; A Stopwatch and an Ordnance Map, Op. 15 (with Robert de Cormier Chorale); A Hand of Bridge, Op. 35 (with Neway, Alberts Lewis, Macro). S of the Air, Golschmann.

NONESUCH D 7°002-Serenade, Op. 1. Los Angeles CO, Schwarz. (Also works by Carter, Diamond, Fine.)

PETERS INTERNATIONAL PLE 059-Serenade, Op. t. Rome CO, Flagello. (Also works by Diamond, R. Green, D. Wilson.) ODYSSEY Y 33230-The School for Scandal Overture, Op. 5; Adagio for Strings, Op. 11; Essay for Orchestra, No. 2, Op. 17; Medea's Meditation and Dance of Vengeance, Op. 23a. New York P, Schippers.

MERCURY SRI 75012-The School for Scandal Overture, Op. 5; Symphony No. 1, Op. 9; Medea, Op. 23: Suite. Eastman Rochester SO, I Janson.

UNICORN UNS 256-Music for a Scene from Shelley, Op. 7; Violin Concerto, Op. 14 (with Thomas); Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Op. 24 (with McGurk). West Australian SO, Measham.

TURNABOUT TVS 34564-Symphony No. 1, Op. 9. Milwaukee SO, Schermerhorn. (Also MAYER: Octagon, with Masselos.)

UNICORN RHS 342-Symphony No. I, Op. 9; Night Flight, Op. 19a; Essays for Orchestra: No. I, Op. 12; No. 2, Op. 17. London SO, Measham.

CBS MS 6224-Adagio for Strings, Op. 11. Philadelphia O, Ormandy. (Also works by Borodin, Tchaikovsky, Vaughan Williams.)

CBS M 30573-Adagio for Strings, Op. 11. New York P, Bernstein. (Also works by other composers.) Penta Ps FESTIVO 6570181-Adagio for Strings, Op. 11. I Musici. (Also works by Bartók, Britten, Respighi.) ARC.O ZRG 845-Adagio for Strings, Op. 11 . St. Martin's Academy, Marriner. (Also works by Copland, Cowell, Creston.) RCA LM 7032-Adagio for Strings, Op. 11. NBC SO, Toscanini. (Also works by other composers.)

RCA AGL 1-3790-Adagio for Strings, Op. 11. Boston SO, Munch. (Also works by El gar, Tchaikovsky.) CBS MS 6713-Violin Concerto, Op. 14. Stern; New York P, Bernstein. (Also HINDEMITH: Violin Concerto.)

TELARC DG 10043-Commando March. Cleveland Symphonic Winds, Fennell. (Also works by other composers.) EVEREST 3282-Symphony No. 2, Op. 19; Medea, Op. 23: Suite. New SO of London, Barber.

MERCURY SRI 7504°-Capricorn Concerto, Op. 21. Eastman-Rochester SO, Hanson. (Also works by Ginastera, Sessions.)

VARÉSE SARABANDE VCS 81057-Cello Concerto Op. 22 (with Garhousova). Musica Aeterna O, Waldman. (Also BRIT TEN: Serenade, Op. 31, with Bressler, Froelich.)

DECCA ECLIPSE ECS 707-Cello Concerto, Op. 22. Nelsova; New SO of London, Barber. (Also RA WSTHORNE: Piano Concerto No. 2, with other performers.) CBS MS 6398-Toccata festiva, Op. 36. Biggs; Philadelphia O, Ormandy. (Also works by Poulenc, R. Strauss, with other performers.)

LOUISVILLE LS 745-Die Natoli, Op. 37. Louisville O Mester. (Also C. ADAM: Cello Concerto, with Kates.) CBS MS 6638-Piano Concerto, Op. 38 (with Browning). Cleveland O, Szell. (Also SCHUMAN: A Song of Orpheus, with Rose.)

TURNABOUT QTVS 34683-Piano Concerto, Op. 38. Ruskin; MIT SO, Epstein.

(Also COPLAND: Piano Concerto.)

NEW WORLD NW 309-Essay for Orchestra, No. 3,0p. 47. New York P, Mehta. (Also CORIGLIANO: Clarinet Concerto, with Drucker.)

(High Fidelity)