Ultra High Fidelity Recordings Sounding Off -- An Interview With Bob Carver

Of Carver Corporation

By Gordon Brockhouse

It's unlikely that any audio designer alive has more innovations to his credit than Bob Carver, forty-five year-old president of Carver Corporation, which he founded in 1978. Virtually every product offered by the Lynnwood, Washington, company contains an unusual circuit with an unusual name: The Sonic Holography generator, the Magnetic Field power supply, the Digital Time Lens, and the Asymmetrical Charge-Coupled FM Detector are among the most well known.

Among high-end audiophiles, Carver is as notorious for his two "T-mod" projects as his products. Accounts of his work have appeared in two "underground" publications: The Audio Critic and The Stereophile.

For both projects, Carver modified his own amps to sound like much more expensive high-end models; these were, in the first case, a Mark Levinson ML-2 mono solid-state amp (costing $6,300 a pair at the time of the test) and, in the second, a Conrad-Johnson Premier 5 mono tube amp ($6,000 a pair). In each instance, reviewers admitted they could hear no differences between the modified Carver and the "target" amps, and a null (output-difference) test confirmed the similarity.

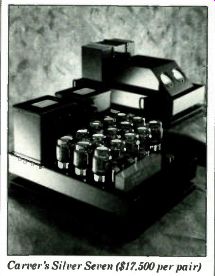

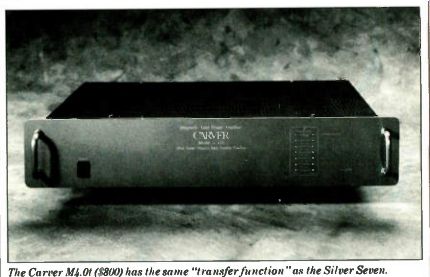

Both challenges resulted in commercial products: the M1.5t and M1.0t power amps, which incorporate the modifications developed during the tests. Since then, Carver has designed his own tubed giant, the Silver Seven, selling for $17,500 a stereo pair. He says he has duplicated its sound in the solid-state M4.0t.

GB: How did the Audio Critic and Stereophile challenges come about?

BC: In each case, I was talking with the editor and said I could make my amp sound like any amplifier, regard less of how it's constructed--whether it's made of grass or glass or tubes.

GB: Is that still your claim?

BC: Oh, absolutely.

GB: What did you actually do in these projects?

BC: First of all, I sat at the lab bench and measured everything about the target amp I could think of, literally hundreds of things. Those measurements can be reduced to an extended mathematical expression that tells me the relationship of the output signal to the input-what is called the transfer function.

Now that I've done it so often, it's almost trivial to replicate all those things in the transistor amplifier. I've done it twice publicly but many times privately. Before the first test, for Audio Critic, I had done it once or twice. The Stereophile told me they'd be using a vacuum-tube amp, so I T- modded a number of tube amplifiers for practice.

GB: Specifically, what did you do to the transistor amp to replicate the transfer function of the high-end unit?

BC: I changed a lot of parameters. I changed the input impedance as a function of frequency. I changed the real and imaginary components of the input impedance. I changed the output impedance of the amplifier and the damping factor as a function of frequency. I changed its gain. I changed its open-loop response and closed-loop response. I modified various bias settings. I changed phase margins and phase shifts. I modified the distortion spectra. In the case of the Conrad-Johnson, I forced the transistor amplifier to generate "large" amounts of benign second-or der distortion components.

My job was not to judge what was making the amp sound the way it did, or even to say which parameter causes what subjective quality. My job was simply to identify all of them, put them all in-all at once-and then to check whether the amps indeed sounded the same.

GB: Given the characteristics of tube-amplifier circuits, some of the changes you made to your amplifier presumably weren't salutary.

BC: Absolutely. A tube-amp output transformer itself has a negative effect. A large part of the circuitry was devoted to mimicking the transfer characteristics of an output trans former. It took op-amps to do this. I had to come up with a circuit that mimicked a transformer's leakage inductance, its distributed capacitance, and the magnetization associated with low-frequency currents in its output.

GB: Did these projects result in changes to the production versions of your products?

BC: With both projects I incorporated the changes I had made-essentially harmless, benign, simple changes- into production-line versions of those amplifiers.

GB: So you added transformer-induced fat, tubey sound to your amps.

BC: In the case of the 1.0t, yes. In the case of the 1.5t, no.

GB: Was that a compromise?

BC: The deal was "warts and all."

GB: The deal for the project. What about the deal for the end user? Does the consumer want warts?

BC: Maybe I shouldn't have done that, but I did. The 1.0t is one of our very best selling amplifiers.

GB: Have you sold many Silver Sevens?

BC: I think I've sold a lot-about fourteen. I can't believe the market that exists for them!

GB: Are you going to duplicate its transfer function in a Magnetic Field Power amp?

BC: We've done it in our 4.0t.

GB: Then what's the reason for having a pair of tube amplifiers that sell for $17,500, when an $800 stereo amplifier can sound the same?

BC: To make a transistor amplifier sound any way I want, I have to have in my possession the transfer function of the target amplifier. So you have to start with something that al ready exists. What I wanted was the world's greatest transfer function.

To get it, I built the Silver Seven. I had come under some criticism for replicating other amps' transfer functions in my products.

GB: That criticism strikes me as spurious. Surely the purpose of any amplifier is to be the proverbial "straight wire with gain."

BC: I felt it was spurious. More than that, I felt it was absolutely beside the point, because the projects began more as an intellectual exercise on my part.

GB: How have the T-mod projects influenced the design of your production equipment?

BC: They've changed some of the things I would normally do if I hadn't been exposed to the T-mod.

GB: What was the fallout of the transfer-function experiments? I gather there was some flack in the high-end press and from high-end amplifier manufacturers.

BC: The people who were upset had a belief system that said this can't be done-it's sacrilegious. People are willing to die for their beliefs. The truth was very upsetting to those belief systems.

GB: The Audio Critic article [which actually is not critical of Carver] implies that the project taught you a lot about high-end sound and the high-end ethos. Is that true?

BC: It was an educational experience. I learned how people think about audio. Something I have found very interesting is how our subjective impressions are developed in our brains and in our hearts and in our souls.

Those subjective impressions may or may not be founded in reality. As a physicist, I feel funny if I don't get a grasp on things, if I can't under stand something from a scientific point of view. It has been important for me to determine what things we hear, how we hear them, when we hear them, how we interpret them.

Part of that is understanding that we hear things that don't exist, or hear differences when they don't exist, and, other times, don't hear differences that are very real.

That subject came up in a late night listening session with one of my friends. ... We were just carried away with the music. I had some Van den Hul silver cables (at $1,000 per meter), but they weren't installed. My friend suggested we install them. We did-and, boy, there was a big difference. We couldn't believe it. The soundstage became wider and deeper. The sound was more lush and more detailed. My friend thought it was great, but I said, "That can't be.

That defies all scientific logic." But there I was-I was hearing it. I said, "Bob, I'm imagining it. You're psyching me into it." And he said, "Nope, it's there," and I had to agree. So I suggested, "Let's unplug them and plug the other cables back in." Sure enough, the sound stage collapsed. It was a little flatter, a little harder, not quite as nice to listen to. And yet, we'd been listening to it all evening and thought it just glorious.

The subjective side of me, my heart and soul, was in a giant battle with my mind. Now, Bob wasn't having that problem. He knew absolutely that the Van den Huls made a big difference. But I knew better. I thought, "What's going on? I know this can't be true." So we changed the cables back and forth several more times. I began not to hear the difference, the difference that scientifically could not possibly be there. He continued to hear the difference as big as life. I said, "I bet you can't hear it if you don't peek at which one is hooked up." So he closed his eyes, and I hooked up the Van den Hul and he listened. And he closed his eyes again and I hooked up the other cables.

Sure enough, he could not tell which one he was listening to.

He was absolutely stunned. He would have bet me a million bucks that he could easily tell the difference. After I had listened to them a couple of times, there was no difference to be heard. Scientifically there wasn't; and subjectively there wasn't.

GB: So what was right: your first impression or your later impression?

BC: My later impression was absolutely the right one. The first one was my imagination at work.

GB: Taking the conversation back to your amplifiers, would you speculate that an audiophile might be more comfortable seeing a great big tube monster than a little transistorized box? And might he let that comfort influence what he hears?

BC: I think that happens sometimes.

But it's so real. It does sound better when you peek at the tubes glowing, or you peek at the Van den Hul cables. It sounds genuinely better.

GB: But those little vibrations in the air are the same.

BC: They're the same.

GB: So it's between the ears where the differences are perceived.

BC: It's between the ears, but it's real. Look, stereo is an illusion any way, and that's a real and important part of the experience. So it's legitimate.

GB: A real illusion.

BC: It's part of the illusion, it's real.

Whatever you need to make the illusion work is legitimate.

GB: Let's talk about your other products. I don't think you have ever brought out a product without some special feature, like Magnetic Field power supply or Sonic Holography or Digital Time Lens. These aren't just technical innovations, they're a great marketing tool, obviously a great help to dealers selling the products. What comes first, the technology chicken or the marketing egg?

BC: The technology chicken. We're basically an engineering-driven company.

GB: I take it that Sonic Holography was the development that put the then-new Carver Corporation on the map. What's the theory behind it ?

BC: One of the reasons a stereo sys tem doesn't sound the same as a live performance is interaural crosstalk.

In real life there are two sound arrivals for each sonic event-one in each ear. Your brain uses those two arrivals to create a sense of location by temporal means, comparing the sounds in the two ears. In stereo you have four sound arrivals--two speakers, two ears. As a result, the temporal cues are confused. Your brain has to ignore them and concentrate only on the amplitude cues to build a soundstage in the mind. The sound stage becomes flattened. If you can somehow get rid of the two unwanted sound arrivals, you create something that's more like real life. It has a sense of depth, space, and temporal reality it doesn't have ordinarily.

Imagine someone coming up and whispering in your ear. You can readily tell that someone's whispering in your ear, because the sound is basically in one ear and one ear only.

If you made a recording of that sound and played it back through a set of speakers, you'd locate it, very accurately, as coming from the left speaker. Obviously that's a tremendous spatial distortion, because it should have sounded like it was coming from outside your left ear. With Sonic Holography, shortly after the sound is launched by the left speaker, the right speaker launches a sound wave that is phased and timed and spectrally adjusted so that it cancels the sound from the left speaker arriving at the right ear. Now all you hear is the sound in your left ear, and you'll hear the whisper as if it were in your left ear.

Carver's Silver Seven ($17,500 per pair)

GB: Surely that can be done for only one room location, though?

BC: If you work out the math, it works as long as the listener-to speaker distance is the same for both channels. As you move in closer, the time it takes for sound to go around your head increases in the same amount as the angle of displacement is changed. But it starts to break up if the listener moves laterally. As you move off the center axis, the illusion of depth begins gradually to collapse.

After a foot, it starts to go away rap idly, back to normal stereo.

GB: Don't good stereo recordings take interaural crosstalk into ac count? Aren't you correcting for something that skilled recording engineers consider?

BC: There's no way that a skilled re cording engineer can make the sound cancel at the other ear. What he can do is make a recording that exploits all the ambience in the hall: use an amplitude-sensitive center mike with outriggers that pick up timing cues.

What the engineer relies on is random cancellations. Just by luck, some of the sonic events and the mike spacing will add in such a way that there will be some partial cancellations.

Some of the finest orchestral recordings do that, and they give a lovely sense of acoustic space.

GB: Have you looked at owners' listening habits? Two years after buying a Carver preamp, is the Sonic Holography button still pushed in?

BC: It depends on the person. Some people have a listening setup where they've really gone to the trouble to make the Sonic Hologram work properly. You have to work at it. To make it work best, the room should be dead end, live-end. The speakers should be pulled away from the back and side walls, because early reflections tend to destroy the Holographic illusion.

And you have to sit between the speakers. The rules are no different from those for normal stereo. The difference is that you have to pay strict attention to them.

GB: Do you need a dentist's chair with a clamp to hold your head in place?

BC: Oh no, it's not like that at all. I de signed it so that you could sit in a chair on the listening axis and have the same freedom of movement as in a chair in a concert hall.

GB: I gather that your receivers, CD players, and car decks are produced offshore, and the rest in the United States. What has been the effect of fluctuating currencies on your company?

BC: We've fallen on hard times. Currencies are not the only factor. The company is doing $27 million now, and that's large enough that we have to change from an entrepreneurially managed company to a professionally managed company. That transition is much harder than I thought it would be.

GB: Do you anticipate moving production of any of your products out of Japan and Germany, back to North America?

BC: About 35 percent of our equipment (in dollar terms) is made in Japan. Right now we're working with our Japanese partner to build in the United States. They are going to make parts kits for us, and we're going to do final assembly. They're going to teach us how to do it the way the Japanese do it-which is fast and furious. We're going to do CD players, tuners, and preamps. We've just recently moved to the old Phase Lin ear building, so we have this 35,000 square-foot building in which we hap pen to make speakers. The other half is going to be this high-speed Japanese-style production line.

GB: Does the yen situation represent an opportunity for North American manufacturers to grab back some of the business they lost to Asian suppliers?

BC: I don't think so. First of all, the Asian suppliers have not raised their prices, and in some cases, they've actually lowered them. Unless they raise their prices a lot, we still wouldn't have the ability to be particularly competitive. You have to re member that the United States has lost the infrastructure that supplies consumer-electronics parts. All that's gone. It took us 20 years to lose it, and it would take another 10 or 15 years to build it up again.

Secondly, the Japanese buy their raw materials on the open market in dollars. What happens is that their materials costs go down as the dollar crashes. The net result is that their costs go down-except for labor, which is only a small component. The greatest cost is moving the product into the American market (commissions, etc.). So their costs go down when the dollar crashes. So it doesn't afford us an opportunity.

GB: What's next for Carver?

BC: This is really an exciting field.

It's why I love audio so much. The stereo systems we listen to today don't present us with a true illusion.

Yet this whole industry's working so hard to do that. We have power amplifiers with essentially zero distortion.

We have loudspeakers whose distortion at any rational listening level is below the human hearing envelope.

The bandwidth of loudspeakers is plenty big. So how come it doesn't sound real? The reason it doesn't sound real is that we're not presenting the proper cues. There are some really smart people working on that. We've seen Yamaha and Bose do some psycho acoustic work. There's not enough psychoacoustic work done, so I have to tip my hat to anyone doing it. What I want to do next is develop a system that will accurately deliver all the proper cues, so that when we close our eyes we can believe we're in the presence of real, live orchestra.

The Carver M4.0t ($800) has

the same "transfer function" as the Silver Seven.

GB: Do you think that's do-able? Can you bring the Berlin Philharmonic home?

BC: It's do-able, with one fundamental limitation: It's not possible to do a facsimile reproduction-meaning exactly the same. If you can forget about facsimile reproduction and concentrate on believable reproduction--so you can close your eyes and say, "That event could have been real," because it sounds real--you can do that.

GB: What do you have to do in the audio chain to make that happen?

BC: I'm not sure yet, because I'm still working on it. But I've been doing a lot of research and I have a lot of ideas.

GB: Such as?

BC: The first thing you have to do is present to your ears the proper timing cues and the proper spectral cues, so that your ear/brain will build this illusion. To do that, you have to get rid of all the wrong cues from your listening room and your speakers.

GB: How do you get rid of them?

BC: A live-end dead-end room is a be ginning, but only a beginning. I'm not sure how to get rid of them all, but I'm working on it. Cancellation techniques perhaps; perhaps live-end dead-end; perhaps the right amount of spectral directionality associated with loudspeaker waveform launch.

After you've gotten rid of all the bad stuff, if you were then to superimpose the proper cues, you could create in the space around your ears a sound field that has what human beings are used to listening to-and it could represent a real, live event.

That's do-able with today's technology. That's the beginning. All of this is just the beginning of really explosive research.

--- Gordon Brockhouse has been an editor of Canadian audio and computer industry trade publications. ---

Also see:

Bits & Pieces -- The real reason to want an 18-bit CD player. (Jan. 1988) DAVID RANADA