THE EAGLES -- "As far as we're concerned, the bottom line is the songs"

"... what we want to do is ... upgrade the lyrics and the appeal of country music."

By Al Parachini

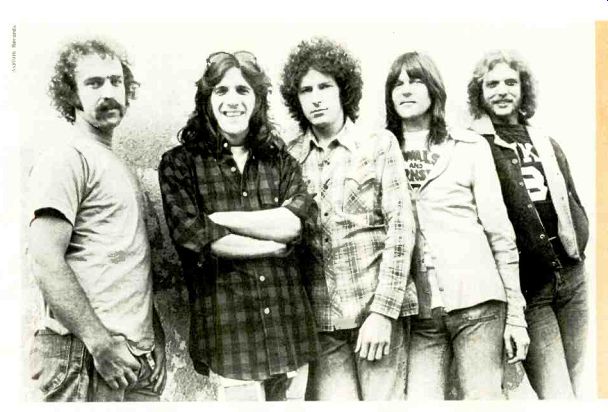

---- The Eagles left to right: Bernie Leadon, Glenn Frey, Don Henley, Randy Meisner, Don Felder

IF there is a new musical messiah coming, he, she, or it is now well over due, and if you happen to be a member of any of the music-industry congregations centered upon Los Angeles, San Francisco, or New York, the anxiety generated by the waiting is by now almost unbearably intense. Truth to tell, rock has been creatively stagnant--at least relative to the appearance within the medium of another starry visitation such as Elvis Presley or the Beatles-for at least five years, and during most of that time many people have been wondering just when the new musical savior will "...what w upgrade appeal o appear, who he will be, and, particularly, what he will be like. But watched pots do not boil, and it is conceivable that simply because so many people have been sit ting around impatiently waiting for it, the second (or third) coming has been indefinitely postponed.

In the meantime, rock has been perpetuating itself through what can only be described as incest. It has become so common for so-called "new" groups to be formed merely by reshuffling the members of older ones that the music industry (on this level at least!) is starting to resemble professional sports, in which players are shifted from team to team by trade, sale, or waiver.

Rock today can be said to be under the domination of third-generation groups that were themselves formed from secondary reorganizations. The Buffalo Springfield, for example, begat portions of Poco and of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. These secondary groups, in turn, produced Loggins and Messina, the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band, and the splintered efforts of the CSN&Y individuals. Another example is the Eagles, a quartet which is at once simply another regrouping of spare parts and something very special: it draws its inspiration quite candidly from the examples of the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, the Beach Boys, and the Beatles, but it adds to it a curious and completely original dimension of technical perfection.

In its first incarnation, the Eagles consisted of Glenn Frey, Bernie Leadon, Randy Meisner, and Don Henley, and it might be well to see just who they were.

Meisner met Richie Furay and Jim Mes sina in Nebraska just before the Buffalo Springfield broke up, then joined them professionally in the early days of sec ond-generation Poco. Leadon emerged professionally in San Diego playing with Dillard and Clark, a group dominated by ex-Byrds, then continued this development with the Flying Burrito Brothers, another part of the Byrds legacy. Hen ley, a native of Texas, met Kenny Rogers on a First Edition tour and ultimately migrated, under Rogers' influence, to Los Angeles, where he played with a group called Shiloh, which evolved somewhat and became the late Manassas, the back-up group for Steve Stills (of CSN&Y, of course, if you are still with me). Frey, the least incestuous of the Eagles, sprang almost miraculously out of Detroit, where he had been profoundly influenced by Bob Segar, whose various bands have been very influential on other professionals even though they have not had much effect on the public.

Anyway, the four fledgling Eagles eventually fluttered separately to Los Angeles, where they landed by splendid accident in the middle of a clique that was fast becoming rock's new dynasty--Messina, Furay, Jackson Browne, and Linda Ronstadt (who is, of course, the former lead singer of a lesser farm-club group, the Stone Poneys). First individually and later collectively, the Eagles-to be met one another through Linda and ultimately became her back-up group.

In 1972 the quartet became officially the Eagles (choosing the name after an at least superficial study of the religion of the Hopi Indians, who revere the eagle as the most sacred of animals), signing on with David Geffen (then an artists' manager as well as the head of Asylum Records), who was as deeply involved in the rebirth of certain ex-Beach/Byrds/ Buffalo/Beatles members as they them selves were.

Geffen sent the Eagles off to England to record under producer Glyn Johns, whose previous clients had included the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Traffic, and the Who. The result was the album "Eagles," Asylum SD-5054. The album produced a hit single, Take It Easy, and was followed in mid-1973 by "Desperado" (SD-5068) and its single, Tequila Sunrise, the instrument with which the group proved itself the most successful of the incest groups. So back they went to England in late 1973 to record their third album, "On the Border" (and, incidentally, to sign on slide guitarist Don Felder as Eagle No. 5). The single Al ready Gone was a sizable hit from that session, as has been, more recently, the ballad Best of My Love.

Glenn Frey gives credit for all this to Glyn Johns: "He's really what made us different and set us apart. It would have been easy for us to stay in L.A. and re cord, but we didn't. First, Glyn's an English producer, and he feels more comfortable technically in the studios over there. But the most important thing is that by going to England we just avoided a lot of distractions. We were able to divorce ourselves from all our usual hang-outs." (The third album was completed in Los Angeles, however, with producer Bill Szymczk at the helm, the "distractions" having proved less distracting, perhaps, with success. Szymcyk is also the producer of the fourth al bum, "One of These Nights," which is reviewed in this issue.) "We're a combination of all kinds of things," says Frey. "We know that we're really a product of the Byrds, the Buffalo Springfield, and others, and that's not necessarily a distinctive thing these days. But by taking our conception of those influences to England and giving it to Glyn Johns, it got refined and became more clear-cut." "Desperado," a concept album, tried to draw a few romantic parallels between the images of the Western outlaw and the rock-and-roll musician. It was a calculated risk, but the group elected not to play it safe: "We could have done another album just like the first one, then put a picture on the cover of all of us sitting in a field with our shirts off," said Frey.

Geffen booked Eagles conservatively, putting them on the road with Procol Harum and Jethro Tull, then getting them top-bill concerts of their own. By the summer of 1973 talk about Eagles was in terms usually reserved for only the most successful of groups, and their flight since has been sustained and strong-though not without the problems success itself brings.

"Some days success is a mind boggle: other days I can put it in perspective," says Henley, who speaks with a soft Texas drawl and is noticeably calmer than Frey and Leadon, both of whom sizzle with nervous energy. "But some times it even gets too much for me," complains Frey. "The elements of the business seem to control you. When you have hit records, people tend to assume you're rolling in money and want for very little. I suppose, though, that the idea of 'taking it easy,' which really came across in that song [written by Frey and Jackson Browne], is that you shouldn't get too big too fast." Perhaps because it is already a unique amalgam of country and rock musical roots, Eagles has not presented itself as a "personality" group in the extra-musical areas of costuming, staging, and the like.

The group prefers jeans and T-shirts on stage, and they say very little to their audiences-except when some brief observation skitters across Glenn Frey's mind and machine-guns out his mouth.

There was a theatrical experiment of sorts in the spring of 1973, when the group performed the songs from "Desperado" in front of a Western-style back drop in Santa Monica and beefed up their sound with a modest string section.

It was effective, probably because it was understated.

"As far as we're concerned," says Frey, "the bottom line is the songs. We work a little bit on stage personality, but it's not our main concern. I think we have a strong image-strong in terms of consistency and in terms of ourselves. If you can retain the music as your bottom line, the audience itself will create your aura and your image." It's a simple philosophy as Frey ex pounds it: he wants Eagles to be remembered for its music, and he wants to make a reputation for himself as a song writer. "Beyond that, I don't really care.

We're concerned with the state of the art [of songwriting], and we don't feel like compromising the music for wider public acceptance.

"Country music today is an insult to the intelligence of the average redneck blue-collar worker," continues Frey, to the accompaniment of encouraging nods from the rest of the band. "There are some righteous pickers in Nashville who don't like the way things are going, but they can't change it on their own. Every body has to help." Frey occasionally gets carried away with his missionary zeal, regretting now, for example, that he once told a University of California audience, "It's about time you hippies took country music away from the straight people." It's the kind of thing you don't want to say too loudly or too publicly, since the traditionally conservative country crowd don't take kindly to sentiments that ring so with the political rhetoric of the long haired left.

"If I had it to do over again, I wouldn't put it quite that way," says Frey. "I don't really want to take country music away from them for good-just for a little while, and then give it back after some of us young people have had a chance to have some influence. We've been walking the line, not making any waves: what we want to do, which is upgrade the lyrics and the appeal of country music, we have to lay on them a little at a time." F the Eagles last, as they seem likely to, they should have lots of opportunity to get a little of this work done. And at least some observers, tired of the messiah watch, have begun to wonder whether the next development in popular music hasn't already occurred.

Rock's new forms have in the past the result, if not of immaculate conception, at least of some form of spontaneous creation. The Eagles' success argues strongly that all that may now be over, that the age of miracles has given way to the age of evolution. That's a net loss in the excitement department, of course, but at least we know the system works.

==============

Also see: