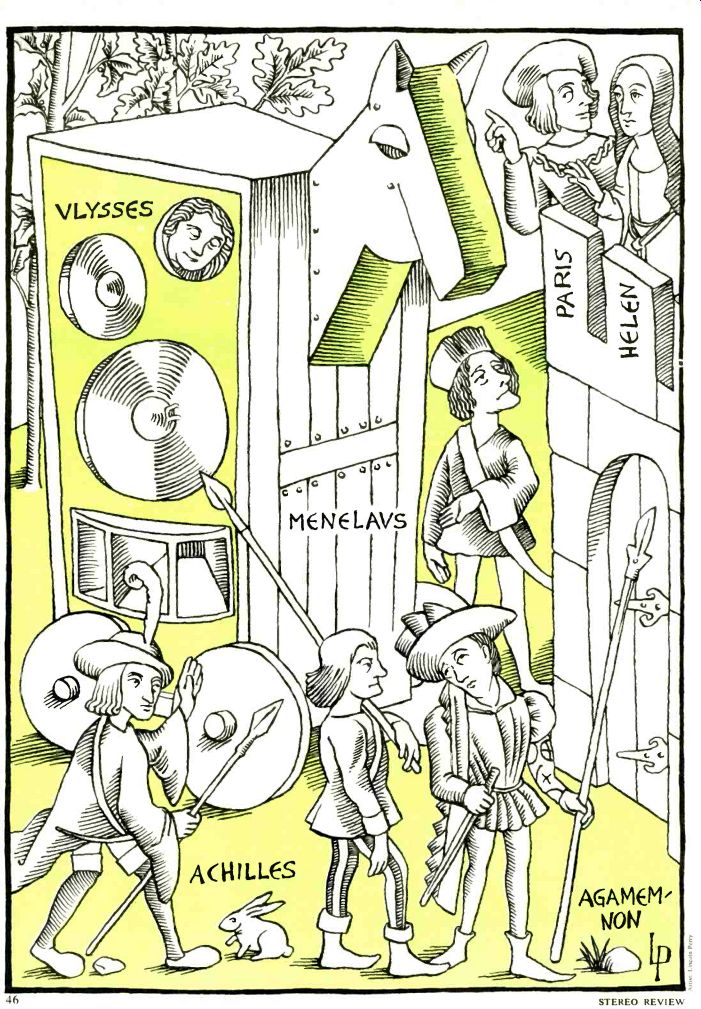

SPEAKER MYTHS---Get rid of that suspect informational baggage before you go out shopping, LARRY KLEIN.

Since speaker design is more mysterious art than exact science, it tends to be a natural magnet for a lot of very fanciful baloney, applesauce, twaddle, and poppycock, which are here exposed by:

Technical Editor, Larry Klein

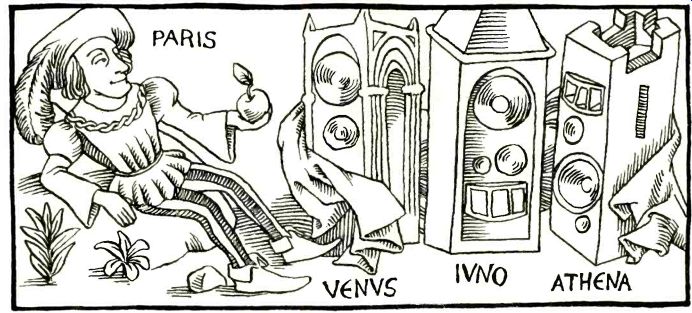

OF all the hi-fi components, loudspeakers offer the audio consumer the very best opportunity to make a bad buy. He not only faces the usual difficult decisions inherent in the purchase of any audio component, but in addition must cope with a hodgepodge of confusions and misconceptions peculiar to speakers as a product category. And even the best intentioned hi-fi salesman is likely to be of little help in separating fact from fallacy because of the probability that he is similarly handicapped by his own treasury of spurious loudspeaker lore. Historically, the attempt to dispel superstition with hard fact has always been a thankless task (consider poor Galileo).

Nevertheless and notwithstanding, I will attempt in the following pages to debunk some of the most well respected, popular (and hence pernicious) myths that make it so difficult for a speaker shopper to arrive at a well-considered choice.

---- I. Everyone hears differently, and that is why people prefer

different loudspeakers.

True, everyone does hear differently; but, Carlos Castaneda to the contrary, we are all listening to the same objective reality. Suppose I set up a microphone and make a perfect anechoic tape re cording of this issue's Reader Service card being shredded by the blades of an electric fan. The tape, when played back (assuming the recording and playback system to be perfect), would, to any listener's ears, sound identical to the original. However, some listeners might nevertheless feel that the reproduction of the card shredding lacks bass, the mid-frequencies have no "presence," or the highs are without "zip." They are certainly entitled to those opinions, but their sonic preferences have nothing whatever to do with high-fidelity--fidelity, that is, to the original sound. The fact that we all do not share the same hearing apparatus therefore has no bearing on our possible disagreement about what constitutes good sound reproduction. This dispute arises because of differences in sonic taste, not differences in perception.

The point is simply this: one is entitled to introduce whatever variations one likes into the reproduction of a sound, but such departures from the original whether produced accidentally or on purpose by a speaker or a tone control--cannot be justified on the basis that "everyone hears differently." The live sound and the reproduced sound are both heard by the same ears in the same way. The two sounds either match reasonably well--or they don't.

II. A bigger speaker is a better speaker.

Some are-but then some ain't. It is usually true that a bigger speaker is a more efficient speaker, assuming that we are talking about a system using conventional dynamic drivers. But isn't a more efficient speaker a better speaker? Yes ... if all other factors are equal-and they very seldom are. It is possible to design a system in a one-cubic-foot cabinet whose bass response goes down lower and comes out cleaner than that of a 15-cubic-foot horn-loaded p.a. speaker.

However, the little unit will not be able to play very loud without severe distortion, and it will perhaps be only 1/100 as efficient as the larger unit. You could drive the big unit to a given sound volume with, say, I watt, while the smaller unit might require as much as 100 watts from the amplifier to reach the same volume level-assuming it could do so with out blowing up. Speaker-system designers who know what they are doing are able to make exactly the compromises they desire, within a given price range, between cabinet size, low-frequency response, low-frequency distortion, and efficiency. The factors are traded off against each other in the final product according to the designer's notion of what the public wants, what he thinks they should have, or some compromise between the two.

III. The more money you spend, the better speaker you get.

The unexpressed assumption behind this myth is that the speaker designers are restricted mostly by cost limitations. If given more dollars to put into the de sign, they will automatically come up with a better product. Oh, would that this were the case! The unfortunate reality is well illustrated by an event that took place in my living room not too long ago.

One evening, at my invitation, manufacturer X brought to my apartment two different pairs of bookshelf speakers: a three-way system selling for about $180, and a four-way job that costs about $40 more. To my surprise, when I went through my usual A-B plus equalizer listening-test procedure, the more expensive and slightly larger four-way system sounded and tested inferior to the three way system.

Seeing that I was somewhat taken aback, the manufacturer hastened to explain that the four-way system was designed as a "step-up." In the jargon of the trade, this means that once the dealer has persuaded a customer to buy a three way Brand X, he might possibly step up the sale by indicating that it would cost only $40 additional to upgrade to a four way system. As my tests revealed--and the designer acknowledged-the price step-up was, in fact, accompanied by a performance step-down--probably be cause of interference between the two tweeters.

The moral to be drawn from the tale is simply this: more is not always better. It is true, however, that a careful and knowledgeable designer can provide legitimate price-point step-ups for the dealer by intelligent manipulation of the design trade-offs discussed earlier. Specifically, the more expensive speaker systems in a given manufacturer's product line should have an advantage in one or more of the following aspects: power-handling capacity (which is related more or less to volume-output capability), efficiency, low-bass capability, high-frequency range and dispersion, or physical appearance (for example, solid walnut trim and veneers rather than vinyl).

It is important to realize that these "trade-offs" in design do not really determine the basic sound of a speaker system. Rather, relatively small frequency-response irregularities in the 70- to 8,000-Hz region are audibly far more obvious and determine a system's specific sonic character ("coloration"). It is the flatness of response in this critical range that to my ear separates the good from the bad-and both of these from the indifferent. The correct handling of the "trade-off parameters" is simply the frosting on the basic cake.

To illustrate: I once spent hours A-B ing a small, two-way, $75 bookshelf sys tem installed atop a nine-driver $600 system, both made by the same company. I proved to my own satisfaction that as long as I kept the volume at a reasonable level, played program material that did not have very-high highs and very-low lows, and listened on-axis, the speakers both sounded excellent-and virtually identical. That is just one good example of proper use of cost-vs.-performance trade-offs.

----- IV. Listening comparison evaluations in a hifi showroom are the

best way to choose a speaker.

This is such an "iffy" proposition that to my mind it qualifies as a myth. First of all, the statement assumes that the listener comes to a showroom with the ability to differentiate between accurate and less-than-accurate reproduction. But even if such a talent is present (actually it's more training and experience than talent), it is frequently very difficult for anyone to differentiate between the inherent performance capabilities of a speaker and the possible peculiarities introduced by the program material or the acoustics of an unfamiliar room. It's not uncommon to have a speaker sound fine in my own living room--and measure well in the lab--yet be sonically disappointing when encountered in some other environment. The reverse has seldom occurred, but it is possible that the choice of program material and/or the acoustic peculiarities of a showroom may by accident (or design) compensate somewhat for sonic aberrations that would be heard as defects under more normal circumstances.

Now that I've shot down showroom evaluation, what is left? That's easy. If you are serious about your speakers and unsure about your ears, the best source of guidance is the speaker test reports in the legitimate hi-fi magazines. Searching out these reports is not as time-consuming a task as it might at first appear since manufacturers who have received good reviews usually have reprints available. Although you will find a certain amount of disagreement on details among the reviewers, to my knowledge none of the legitimate magazines have ever given a really rotten speaker a good review.

Good products, however, for obscure and complicated reasons, do occasionally receive mediocre reviews (elsewhere, of course!).

A note of caution: speaker systems, in general, have improved tremendously over the years. A system we rated as one of the very best five or ten years ago might be judged as simply just another good speaker among many today. For this reason be sure to check the dates on reprints of (or quotes from) speaker re views to avoid being misled. (An index of STEREO REVIEW'S own test reports can be obtained by sending 250 and a stamped self-addressed long envelope to STEREO REVIEW, Dept TRI, One Park Avenue. New York. N.Y. 10016.)

V. The best Way to prepare

pour Self for speaker evaluation is to attend tine concerts.

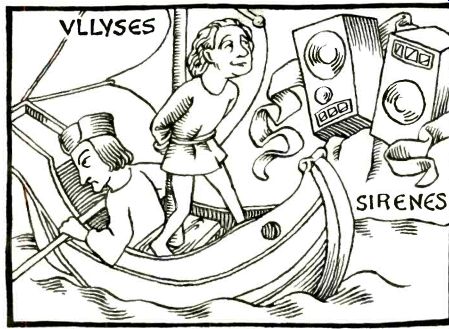

Although I applaud the good intentions of the propagators of this myth, there are several practical things wrong with the idea-aside from the simple fact that recordings only rarely embody the same sound qualities heard in a concert hall. The major flaw has to do, once again, with the nature of auditory perception. Most people hear well enough to make judgments, but they simply do not know what to listen for-even after years of concert-going.

The experienced loudspeaker evaluator consciously or unconsciously divides the frequency spectrum reproduced by a speaker into three general bands: lower, middle, and upper. He then focuses on each frequency band individually and lis tens for typical problems. In other words, he listens for what's wrong, rather than what's right.

In the low band, one should listen for the presence of boom or "barrel effect" on deep male voices. Listen also for weaknesses in the low-frequency range, although this is very difficult to judge except on a comparison basis. For example, a speaker can have a low-frequency peak at, say, 70 Hz and not be able to go much lower, but it will nonetheless sound, on many modern rock records, as though it has better bass than another speaker that goes smoothly down to 40 or 50 Hz (moral: choose your program test material carefully). Such peaked speakers are also usually more efficient than speakers that go down lower and smoother-all of which relates to the design trade-offs discussed in Myth III.

In the mid-range frequencies, listen for a sound quality that's neither too projected (boosted middles) nor too with drawn (depressed middles). The forward type of projection is frequently associated with a nasal, honky quality that shows up in female voices, especially in the middle (rather than soprano) range. A withdrawn quality makes vocalists sound as though they were behind the orchestra rather than in front of it.

In respect to the high-frequency range, I've found a tambourine to be a fine "test instrument": it provides an excellent live standard of comparison.

Note the delicacy, shimmer, and lack of "shatter" in the sound of the live tambourine versus the recording of a tambourine reproduced by speakers. Of course, the phono cartridge and the recording also introduce variables here, but there should be no problem in finding ones that do a proper job. (It should be obvious that I've covered just some of the areas in which speakers can go wrong, but the subtlety of the other effects-and the lack of an accepted terminology--unfortunately precludes verbal description.)

-----VI. The more bass, the better bass.

This myth dies hard, mostly because many speaker manufacturers tend to endorse it, having lost their shirts trying to fight it. For perspective on the question, it's necessary to be aware of the distinction between more bass and lower bass touched on in Myth V. For all of us, the mid-frequencies (roughly 400 to 2,000 Hz) provide a subjective zero-reference point. If this entire range of frequencies were to be boosted, the overall sound would be louder, but there would be an audible loss of highs and lows.

Conversely, if the mid-range were to be depressed, there would be a loss in loud ness and an audible boost in the high and low frequencies. In other words, to the ear it's all relative.

In addition, the amount of bass produced by a speaker system can vary radically in response to its placement and the acoustic character of the room.

Speakers in the middle of the floor or in the middle of a wall produce the least bass. Place them at a floor-wall junction and you have more bass. Install them in a corner and you have the most bass of all. Which is best? Ideally, the level of the bass frequencies should be more or less even with the level of the middle frequencies. In other words, you want a flat frequency response.

But all of this has to do only with the relative amount of bass, not how low the bass goes. The ability--or inability--of a speaker system to reproduce the low bass, say frequencies of 50 Hz and on down, is inherent in its design. The room can either help the speaker realize its low-bass performance potential or pre vent it from doing so. One rough index of a speaker system's low-bass potential is its "in-box" or system resonance specification. Most bookshelf speakers with good low-bass performance have a resonance between 40 and 50 Hz. However, don't confuse the in-box resonance with a woofer's free-air resonance, which is probably specified at under 25 Hz and is not meaningful except to the designer.

VII. There's one best speaker system design, and anyone who learns

enough theory can determine which one it is.

I must confess that this myth is never phrased in language quite this blunt. It is more likely to appear as, say, an oblique question probing into the significance of a specific-and usually novel-driver de sign. Or it may be a question about the relative design virtues of acoustic-suspension vs. aperiodic vs. transmission-line enclosures. In any case, as far as determining how close a particular design concept comes to achieving some ideal of "absolute fidelity" (cost no obstacle), I really can't be of any help since I know of no way to establish the absolute best among the many high-accuracy reproducers we have tested over the years. All we honestly can--and do-say in our test reports is something like "this ranks with the finest speakers available." It may well be that among those "finest" there is one that comes closer to perfection (absolute accuracy) than the others, but we have no way of scientifically making such a fine distinction. More over, in any practical listening situation, differences in program material, the associated audio equipment, the acoustic environment, and room placement will introduce far more variation in the audible outputs of two excellent speakers than might result from the differences in their measured performance.

However, if there were magically to appear on the market a speaker system that sounded and tested as good as "the finest" and was half the price, half the size, and had twice the efficiency, the impossible dream would have been realized--and I would be inclined to judge it the best.

Also see:

SPEAKER PLACEMENT--You cando it yourself because of a nice acoustical reciprocity, ROY ALLISON