EQUIPMENT TEST REPORTS--Hirsch-Houck Laboratory test results on: the Akai GXC-325D stereo cassette deck, Stax SR-5 stereo headphones, Design Acoustics D-2 speaker system, and Lenco L-85 turntable. By JULIAN D. HIRSCH.

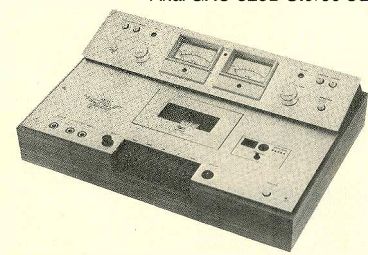

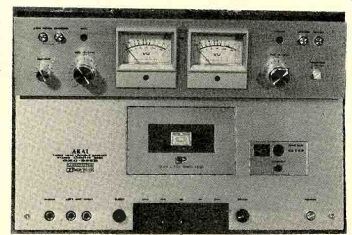

Akai GXC-325D Stereo Cassette Deck

THE Akai GXC-325D is a new member of the slowly growing ranks of three-head cassette recorders. Like some other moderately priced three-head machines, it combines the separate recording and playback heads in a single unit which fits through the single cassette opening originally intended only for a dual-purpose record/playback head. The two heads of the GXC-325D are physically separate, mounted as a unit with a ferrite shield between them to prevent electrical coupling which could dilute the effectiveness of the off-tape monitoring afforded by separate heads.

The alignment between the crystal ferrite heads is fixed at the factory, and because they are so closely spaced there is no likelihood of tape skew between them. The recording-head gap width and playback-head gap width are respectively 4 microns and 1 micron, each optimized for its function. Like other three-head recorders, the GXC-325D has separate electronic sections for recording and playback functions. Since it is Dolby-equipped, there are separate Dolby circuits for the two functions as well as for the two channels-four in all. The electronic circuits are based on discrete components, and the machine has an imposing semiconductor complement of sixty transistors, four FET's, fifty-one diodes, and one integrated circuit (used in its automatic-stop system).

Externally, the Akai GXC-325D is a conventional top-loading machine with the cassette opening in the center of its satin-finish aluminum top panel. The five major transport controls are dished "piano-key" levers along the center front edge of the panel, plainly marked for their functions of stop, play, fast forward, rewind, and record. They are flanked by two round pushbuttons for EJECT and PAUSE functions.

Also located near the front of the panel are the headphone jack, two microphone jacks, and the pushbutton power switch. To the right of the cassette is the index counter, which has a "memory" feature that automatically stops the tape in rewind when the counter returns to a "zero" setting. Next to it is a row of five small amber dots, behind which a moving light indicates tape motion. At normal playing speed, the light travels slowly from left to right, and in the fast speeds it moves rapidly in the direction of tape motion.

In the center of the sloping rear panel section are two large illuminated VU meters with a red PEAK light between them. This is de signed to flash on when momentary peaks of +7 dB or greater occur in either channel. The recording-level controls for the two channels are located to the left and right of the meters.

--------- FREQUENCY IN Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND)

--------- The GXC-325D presents a markedly "clean" appearance, with all controls isolated and clearly distinguished.

Each is a concentric control for separate adjustment of the mixing mic and LINE inputs.

At far left is a single playback-level control affecting both channels. At far right is the MONITOR switch, which drives the line out puts with the input signal or the signal from the playback head.

Along the rear of the sloping panel are two pushbuttons to set bias and equalization for "low noise" (LN) or chromium-dioxide (Cr02) tapes. When both are engaged simultaneously, the recorder is said to be adjusted for ferrichrome (FeCr) tapes. Two more but tons activate the recording-level limiter and the Dolby system. All four buttons have small lights in their centers which glow when en gaged. Amber and red lights on the panel show when the PAUSE and RECORD functions are in use.

The tape transport is completely solenoid-operated, and the keys can be pressed in any sequence without going through STOP. The capstan is driven by an a.c. servomotor with a closed-loop, double-capstan system that maintains the tape under constant tension as it passes over the heads. If the tape stalls, ends, or breaks (or if power is interrupted), the transport shuts off and disengages mechanically. The line inputs and outputs, including a DIN socket, are recessed into the rear of the wooden base. The Akai GXC-325D is about 17 1/2 inches wide x 11 3/4 inches deep x 5 1/2 inches high and weighs 19 pounds. Price: $475.

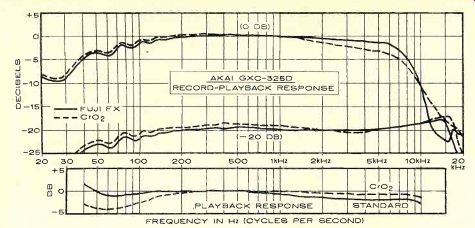

Laboratory Measurements. The playback frequency response of the Akai GXC-325D varied ±2 dB from 40 Hz to the 10,000-Hz upper limit of the test tape. According to the manufacturer, the machine was biased for Fuji FX tape, which we used as the "normal" tape in our tests. For chrome tape we used TDK KR, and the ferrichrome tape was Sony FeCr. At a-20-dB recording level, the Fuji FX tape gave a response with ±2 dB from 80 to 14,500 Hz, with the lower frequencies dropping off slightly. The overall response of ±3 dB from 40 to 17,000 Hz was slightly better than the Akai specifications of 30 to 15,000 Hz. At a 0-dB recording level, tape saturation caused the response to drop rapidly above 7,000 Hz, the-20-dB curve being intersected at 11,500 Hz.

With chrome tape the overall response was ±3 dB from 38 to 19,000 Hz (rated 30 to 16,000 Hz). The 0-dB and-20-dB response curves intersected at 14,000 Hz. The ferri-chrome frequency response was emphasized in the frequency range below 1,000 Hz and generally depressed in the 2,000- to 10,000-Hz range before rising slightly at higher frequencies. Within the ±3-dB tolerance used by Akai to set their specification of 30 to 19,000 Hz, we measured a 37- to 20,000-Hz response with Sony FeCr tape. The 0-dB curve sloped down steadily above 1,000 Hz but remained well above the-20-dB curve all the way to the test limit of 20,000 Hz.

We also made frequency-response measurements with a number of other high-quality tapes in order to judge how critical the match was between recorder and tape. To our pleas ant surprise, the GXC-325D delivered excel lent performance with almost any good tape.

For example, Maxell UD and UDXL and Nakamichi EX II tapes gave almost identical frequency-response curves, similar to the Fuji FX except for a rise of one or two decibels be tween 10,000 and 15,000 Hz. The TDK Audua tape was slightly "hotter" at the high frequencies, but not so much as to audibly color the sound. Akai states that a "normal" tape for this machine is a "low-noise" or premium type, and this was confirmed by the slight roll-off of response above 10,000 Hz with TDK SD and the new 3M Master tape (again, this was not audibly significant).

We do have some reservations about the use of ferrichrome tapes with this recorder, however. Although Sony FeCr tape meets the manufacturer's specifications, the response with it is by no means as flat as with straight ferric (or cobalt/ferric) tapes or with CrO2 tape. The "other" ferrichrome tape, 3M Classic, gave unacceptable results with the recorder's "ferrichrome" switch settings. The average response below 1,000 Hz was some 8 dB higher than the average above that frequency. It was essentially an exaggerated form of the response with Sony FeCr. When the "normal" settings were used with Classic, its frequency response was very similar to that of CrO2 tape.

The "tracking" of the Dolby circuits was acceptable, though not quite optimum. At re cording levels of-20 and-30 dB, the Dolby system produced an increased playback out put of up to 2.5 dB at various frequencies be tween 1,000 and 10,000 Hz.

To reach a 0-dB recording level on the meters, a LINE input of 85 millivolts (mV) or 0.35 mV at the mic input was needed. The microphone inputs overloaded at a reasonably high 62 mV input. The playback output (maximum) was 1 volt with FX and KR tape and 0.83 volt with FeCr. The headphone volume, which was fixed, was too low to be usable with 200-ohm phones. The Dolby calibration mark on the meters was at +2 dB; however, a standard 200-nW/m Dolby tape drove the meters to +3 dB. The meter ballistics were fairly close to VU standards, with a 10 percent overshoot on 0.3-second tone bursts. The limiter began to come into action at-1 dB and was fully effective above 0 dB in preventing distortion due to excessive recording levels. The PEAK light began to glow at +7 dB.

At a 0-dB recording level, the playback distortion with a 1,000-Hz signal was a very low 0.72 percent with Fuji FX tape, 2.1 percent with TDK KR, and 2 percent with Sony FeCr. The recording levels for 3 percent playback distortion were +5, +2, and +1.5 dB, respectively. The unweighted signal-to noise ratio (S/N) referred to that level was 52.5, 52, and 49.5 dB. With IEC "A" weighting, the S/N figures were 57.5, 58, and 56 dB.

Finally, adding the Dolby system improved the S/N to 66, 64, and 63 dB. The noise in creased by an insignificant 1.5 dB through the microphone inputs at maximum gain.

The combined wow and flutter (almost all in the flutter-frequency range) was a very good 0.09 percent (unweighted). In a record-playback measurement it was even lower -0.07 percent, presumably due to some cancellation occurring between the recording and playback processes. In fast forward and rewind, a C60 cassette was handled in approximately 72 seconds.

Comment. The handling properties of the Akai GXC-325D left little to be desired, the transport controls and "feel" imparting a sense of precision that was confirmed by the performance. When we compared the input and output programs using the MONITOR but ton, we were surprised to find that the play back sounded brighter and noisier than the in put signal, This was not consistent with our measurements (even when the Dolby system was not used). However, when the switch was left in its TAPE setting and the amplifier's tape-monitor switch was used for the com parison (as would normally be done), the results were essentially perfect, no difference being heard between the incoming program and the tape playback. The reason for the apparent discrepancy was the slight increase in output level from the recorder (about 1.5 to 2 dB) when switching to TAPE with its own MONITOR switch; this accentuated the residual noise and made the program sound bright.

Although the GXC-325D works well with any good tape, our tests clearly show that it is at its best with a good ferric tape such as Fuji FX (or the others we tried). These tapes not only produce the flattest frequency response and lowest distortion, but give a substantially better S/N as well. The added recording "headroom" afforded by the Fuji tape makes the PEAK light a useful feature, since any level that flashes the light only occasionally will be within the machine's dynamic range. This is not necessarily true with chrome tapes, which may saturate before the light flashes.

++++++++++++++

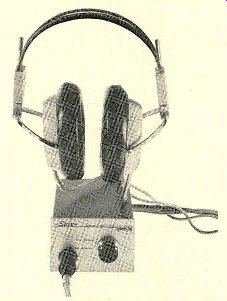

Stax SR-5 Stereo Headphones

STAX, one of the major brands of electro static headphones sold in this country, is imported by American Audioport of Columbia, Mo. The Stax models range in price from very moderate to very expensive, and the SR-5 phones fall in the middle of the price range.

For electrostatic headphones, the SR-5's are atypically light and compact: they weigh a mere 13 3/4 ounces and rest lightly on the ears with their soft, fluid-filled cushions. Although they are circumaural phones (completely covering the ears), they offer little blockage to outside sounds.

Like other electrostatic phones, the SR-5's require a polarizing power supply and step-up transformer driven from the amplifier's speaker outputs. These functions are included in the SRD-6 adapter, a small box measuring 3 1/2 inches wide, 2 1/2 inches high, and 75/s inches deep, which consumes only 0.1 watt from the 120-volt a.c. power line and can be left energized at all times. If the adapter displaces a pair of normally used speaker out puts on the amplifier, the speakers can be connected to terminals in the rear of the SRD-6, and a switch on its panel activates either the speakers or the phones.

SR-5 phones have a braid-covered cord about 7 1/2 feet long, with a special plug that mates with a socket on the SRD-6 panel. They cannot be driven from the usual headphone output jacks of an amplifier or receiver. The performance of the SR-5 system is specified separately for the headset and the adapter, but the most important rating (for the user) is the maximum continuous input of 8 watts at 1,000 Hz (momentary peaks should not exceed 30 watts). Caution is suggested if the phones are to be connected to a high-power amplifier, since they could be damaged by continuous power levels exceeding 15 watts.

The maximum rated sound-pressure level (SPL) from the SR-5 phones is 110 dB, and their frequency response is stated to be 30 to 25,000 Hz. Price: $125, including the SRD-6 adapter.

Laboratory Measurements. As measured on a modified ANSI headphone coupler or "artificial ear," the Stax SR-5 phones had an extremely smooth and flat response through the important bass and mid-range-within ±1 dB from 67 to 600 Hz. The output was "shelved" at lower frequencies, so that the 20- to 45-Hz response was about 7 dB be low the mid-range level. Above 1,000 Hz there was a moderate amount of irregularity in the response curve, though less than we have observed with most phones. Since in this frequency range the coupler dimensions can have a profound effect on the response measurement, it is not easy to determine how much of the irregularity is due to the phones them selves. However, the output remained strong all the way up to the 20,000-Hz test limit, and the overall variation of ± 7 1/2 dB from 20 to 20,000 Hz is excellent for a headphone. The electrical impedance at the input to the SRD-6 was between 15 and 28 ohms from 20 to 8,500 Hz, falling to 7 ohms at 20,000 Hz.

With an input of 2.8 volts to the SRD-6, (corresponding to a 1-watt amplifier output into an 8-ohm load), the SPL from the phones was 102 dB through the flat mid-range region.

We measured total harmonic distortion (THD) at several frequencies, with nominal drive levels of 1 watt and 10 watts. At 1,000 Hz, the THD was between 0.2 and 0.25 percent, varying little with power (the SPL with 10 watts input was a very loud 115 dB). In spite of the extended high-frequency response of the phones, driving them with a 10-watt level at 10,000 Hz produced only 0.23 percent THD. In the bass region, the larger diaphragm excursion results in greater distortion just as it does with a loudspeaker. At 50 Hz, the THD was 1.6 percent at 1 watt and 13 percent at 10 watts.

Comment. As with a loudspeaker, a head phone's sound can best be judged by listening (although its measured response can give some clues as to what it will sound like). The Stax SR-5 listening qualities were completely consistent with our measurements. The sound had the almost indescribable smoothness and clarity that has long been a hallmark of good electrostatic sound, whether from a speaker or a headphone. Although we had no difficulty driving them to very comfortable listening levels from a moderately powerful amplifier (25 watts or more), these phones cannot be expected to produce the ear-shattering levels possible with some dynamic phones. Not only would this require the use of an amplifier capable of at least 100 watts per channel, but the phones would probably be destroyed in the at tempt to drive them to those levels.

Aside from their sound, which is unexcelled, the most striking feature of the SR-5 phones is their comfort. We have often found some of the best headphones (from an acoustic standpoint) to be unwearable for any length of time because of weight or spring pressure on the ears. The featherweight Stax, in sharp contrast, can hardly be felt; the result is a much more realistic musical listening sensation than we have experienced with most circumaural phones.

++++++++++++++

Design Acoustics D-2 Speaker System

FROM all indications, the loudspeakers made by Design Acoustics, Inc. have been engineered to generate a flat power response through the audible frequency range and to radiate more or less omni-directionally or at least hemispherically. The company's first product, the dodecahedral (twelve-sided), eleven-driver Model D-12, certainly met those goals. So, too, did the subsequent Model D-6, despite its conventional-looking floor-standing cabinet.

Next came the D-4, a column-shaped speaker that managed to retain much of its predecessors' open, dispersed sound quality.

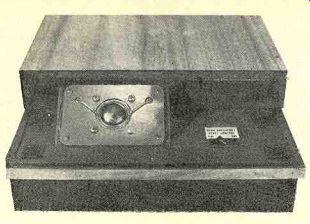

In our published evaluations of these three models (January and September 1973 and January 1975, respectively) we found that they set very high standards for "natural" sound quality. Now Design Acoustics has introduced the D-2, the first of its products that does not employ multiple tweeters. It is a two way system with a single 10-inch long-throw woofer and a 1-inch dome tweeter, crossing over at 1,500 Hz. Like the D-4, the D-2 is also columnar, standing 34 inches high and 121/4 inches square; it weighs 35 pounds. Three of its sides are covered with a black grille cloth; the top is walnut, with a piece of acoustically transparent black foam plastic covering the top-mounted tweeter, which is angled for ward and upward at 30 degrees to the vertical.

A rocker switch next to the tweeter reduces its output (from a designated flat setting) by 3 dB to adjust the system for use in acoustically bright rooms.

The woofer is in a fully sealed enclosure. It has a free-air resonance of 23 Hz, which is in creased to 41 Hz by the air load in the cabinet.

The nominal impedance of the D-2 is 8 ohms, and it is recommended for use with amplifiers rated at 20 to 50 watts per channel. Instead of the more usual loosely defined frequency specification, the D-2 carries a power-response rating of 40 to 18,000 Hz dB.

According to Design Acoustics, the tweeter delivers an essentially flat power response throughout its operating range. Since any single radiator of conventional design becomes directional at high frequencies, the tweeter response on axis has a rising high-frequency characteristic. However, the tweeter's pres sure response 60 degrees off axis (that is, in a horizontal plane around the speaker) is flat and matches the shape of the overall system power-response curve. Angling the tweeter upward provides a more uniform sound field for a listener, and without the "hot spots" that often occur directly in front of a speaker. Price: $150.

Laboratory Measurements. Since our live-room test method is intended to approximate a total power-response measurement, we were interested to see how closely the. D-2 lived up to the claims made for it. With the tweeter level set to "fiat," our composite frequency-response curve was strikingly flat and smooth, with a variation of only ±2 dB from 40 to 15,000 Hz. The extraordinary agreement between our measurements and those used by Design Acoustics to establish their ratings was gratifying, needless to say, especially since they were made under completely different test conditions. It is clear that the D-2 system has a remarkably flat response-not only compared with others in its price class, but at any price.

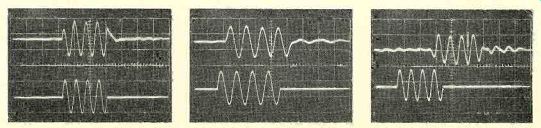

The D-2 has fairly low efficiency, delivering a sound-pressure level of 87 dB at a distance of 1 meter from the front of the cabinet when driven by one watt of mid-range random noise. The woofer distortion, though not excessive, was not particularly low. It measured 1.5 to 2.5 percent down to 50 Hz at-a 1-watt drive level and increased smoothly to 10 percent at 30 Hz. With a 10-watt input the distortion was appreciably higher. It measured 6 to 8 percent down to just below 50 Hz, and 17 percent at 30 Hz. When not overdriven, the woofer sounded as clean as any we have heard. Tone bursts were reproduced cleanly at all frequencies, with virtually no ringing or start-up delays.

------------ The consistently fine tone-burst response of the

D-2 is illustrated in these oscilloscope photos taken at (left to right)

100, 1,000, and 10,000 Hz.

-------- The angled dome tweeter, visible when the foam grille is

removed, provides uniform horizontal dispersion of the higher frequencies.

The tweeter-level switch is at right.

The tweeter-level switch began to attenuate the highs above 1,500 Hz, with a shelved response drop of about 3 dB at most frequencies above 2,000 Hz. The system impedance was 8 to 15 ohms over most of the frequency range, with a broad minimum of about 7 ohms above 6,000 Hz and a bass-resonance peak of almost 40 ohms at 41 Hz.

Comment. In the simulated live-vs.-recorded test, the Design Acoustics D-2 was a virtually perfect imitator of the original sound. Usually the results were more accurate with the highs flat, but sometimes we felt that the-3-dB setting was more accurate.

Throughout the test we were pleased to find that there was no lower-mid-range heaviness to color the sound (a common flaw that frequently prevents a speaker from achieving a top rating in this test).

From this, and from our measurements, we would expect the D-2 to be a very smooth, neutral-sounding speaker. It was all of that.

We preferred to place it well away from the room walls to minimize any tendency toward heaviness that might result from the bass enhancement of such placement. The woofer response is inherently so flat well into the low-bass region that such augmentation could only reduce the natural quality of the sound.

We found that the speaker is, for all practical purposes, omnidirectional in the horizontal plane (the hemisphere into which it faces), and there is no audible vertical directivity un less one stands so close as to approach the tweeter axis. We also found it so easy to listen to (probably because of the lack of coloration) that we speedily forgot that we were listening to a speaker. In our view, the D-2 is certainly one of today's real speaker bargains, and it deserves the most serious consideration if you are interested in a good-sounding, good looking system that takes up no more than a square foot or so of floor space.

+++++++++++++++++

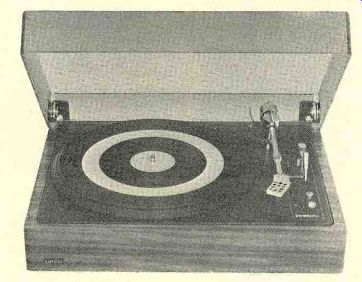

Lenco L-85 IC Turntable

THE Swiss-made Lenco L85 IC is a manual record player that automatically lifts the tone arm and shuts off the motor at the end of a record. The 40-ounce, nonferrous platter is belt-driven at 33 1/3 or 45 rpm by a slow-speed (450 rpm) synchronous motor. Although the speed change is mechanical (accomplished by shifting the belt on a stepped shaft), the motor is driven and controlled electronically and its speed can be trimmed electrically over a range of -3 to +7 percent. The "IC" nomenclature refers to the use of integrated circuitry in the motor-drive/control system.

The tubular tone arm has a lightweight removable cartridge shell with adjustable cartridge position. A template is supplied so that the stylus overhang can be set for minimum tracking error near the inner grooves of a record. Two counterweights make it possible to balance the arm with cartridges of almost any weight. Anti-skating force is applied by a weight hanging on a thin nylon cord. The position of the cord on a notched bar on the arm adjusts the amount of outward torque applied to the arm, and two anti-skating weights are provided to match any reasonable tracking force (recommended settings are given in the instruction manual).

After the arm is balanced, the tracking force is set by sliding a small weight along the arm tube. There are calibration marks at 1-gram intervals from 0 to 5 grams.

The operating controls of the Lenco L-85 IC are grouped at the right side of the motorboard. At the front are the on and off pushbuttons, which operate with a very light pressure. Behind them is the cueing lever, which lowers the pickup when it is pulled forward against a slight spring pressure. When it is re leased, either by a slight push or automatically at the end of a record, it moves abruptly to the rear and the tone arm is lifted.

A small knob shifts the belt on its drive pulley for speed selection, and behind it is a vernier speed control. Stroboscope markings on the beveled edge of the platter are illuminated from below and can be used to monitor or ad just speed while playing a record. The rubber mat has three narrow rings that support the record only at its edge.

The entire record-player mechanism is suspended from its finished wooden base on viscous-damped spring mounts. The springs can be adjusted individually for turntable leveling. The smoky-plastic dust cover is hinged to remain open at intermediate angles, and it can be removed easily. The L85 IC, complete with base and cover, is 18 inches wide, 14 inches deep, and 5 1/2 inches high; it weighs 21 pounds, 10 ounces. Price: $299.50.

Laboratory Measurements. With a good high-compliance cartridge installed in its shell, the arm resonance of the L85 IC was at 8 Hz with an amplitude of 6 dB. The mass of the arm is evidently low enough that almost any currently manufactured cartridge can be used effectively. The actual stylus force was about 0.2 gram higher than indicated at most settings (an insignificant error). The tracking error was less than 0.5 degree per inch at radii from 2.5 to 6 inches, and it was essentially zero over the inner half of a 12-inch record.

The arm wiring and cable capacitance was 235 picofarads per channel, which is about right for most stereo cartridges but too high for CD-4 cartridges.

Comment. We must confess to having a mixed reaction to the Lenco L-85 IC. On the plus side of the ledger, it is an outstandingly fine record player. The arm is low in mass, has low bearing friction, and is easy to handle (though the finger lift comes off too easily when used to push the arm into its rest clip).

The turntable itself is superb-certainly the best belt-drive unit we've seen from the standpoint of rumble (only a couple of direct-drive models have measured slightly better in our tests)-and we have already commented on the outstanding base isolation.

Most of the minor annoyances we have mentioned would not in themselves detract seriously from the fine qualities of the L-85 IC. Our real reservations concerning the turn table relate mostly to quality control. We have tested two units (one was the earlier L-85, sans "IC", but it was essentially identical to the latest version in its performance).

As received, both had the same fault-an inoperative cueing and arm-lift system. Examination revealed that the control linkage had come apart, and a certain amount of delicate bending was necessary to restore it to operation. Also, in both samples a small coil spring was found hanging from a portion of the mechanism-and with no clue to where its other end belonged.

To put the matter into perspective, and to leave no doubt as to our feelings, if the buyer of a Lenco L-85 JIC checks out the unit at the dealer's to be sure that the cueing device functions properly, and if the cartridge can be mounted and positioned by the dealer or someone with a good assortment of mounting screws (the ones supplied are not usable with many cartridges) and a very fine screwdriver (essential for the cartridge-overhang adjustment), he can put the unit into service with the knowledge that he owns one of the best-performing record players on the market.

The turntable speed was independent off a.c. line voltage. The vernier range was from -3 to +9 percent. The turntable was one off the quietest belt-driven units (from a rumble standpoint there was absolutely no audible acoustic noise) we have tested, and in fact surpassed many direct-drive turntables in its freedom from vibration at any frequency. The unweighted rumble was -36 dB including vertical components, -40.5 dB with vertical rumble canceled out, and a very low -60 dB with ARLL weighting. Wow and flutter were each 0.035 percent, giving a combined reading of 0.05 percent at either speed.

As so often happens, the anti-skating had to be set about 0.75 gram higher than the tracking force. The cueing lift behaved quite differently from most we have used. On the L-85 IC, the descent appeared to be well damped and drift-free, but the lift was abrupt and bounced the arm clear of the lift bar, which caused the arm to move toward the outside of the record by a visible amount. A slow movement of the cueing lever did not help, since the mechanism is spring-loaded and operates abruptly when triggered.

The 7-, 10-, and 12-inch index notches on the lift bar worked very well-in fact, too well: we found it difficult to cue the arm to, points in close proximity to the notches with out having it slip into them. However, the supplied lift-bar covering clip solved that particular problem.

The viscous-damped isolating springs were highly effective against external vibration that could cause acoustic feedback. At frequencies between 20 and 100 Hz, the isolation was 10 to 30 dB better than that of most turntables we have tested. Because of the damping, the unit is not, in the least sensitive to ordinary handling shocks, so that we were able to operate it without the "kid gloves" approach needed with some softly sprung but undamped record players.

------------

Also see:

UNDERSTANDING RECORD PLAYERS: What you should know before you go out shopping, JULIAN D. HIRSCH

In the Groove: Close-Up View of Record Wear (Audio, Sept. 1980)

AUDIO QUESTIONS and ANSWERS--Advice on readers' technical problems