by RALPH HODGES

THE CUSTOMIZED TUNER

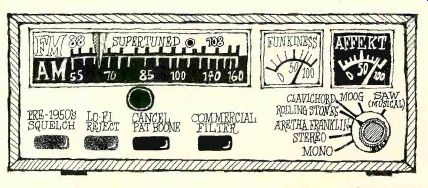

WITH its single main control and easily interpreted meters, the tuner has traditionally been one of the simplest audio components to operate. But of late there has been a realization among tuner manufacturers that complexity in pursuit of better performance is sometimes no vice, and their current products reflect this attitude more and more. In today's tuners (and in the tuner sections of receivers) we're seeing a proliferation of knobs and switches that do things that could not be done with older products. Furthermore, in many cases these facilities can tailor and even augment the audible FM performance (as opposed to providing convenience and ease of operation), and frequently they require a decision by the user as to what compromises he will or will not accept in his reproduced sound. Hence these new controls are-or can be-useful adjuncts to listening pleasure. But before they can be used effectively they must be understood.

Since few of us really know how an FM tuner works (and those of us who do are prone to forget at any given moment), pitching this discussion on the theoretical plane would probably be unwise. Therefore, what follows will be a largely pragmatic treatment of what these sound-altering controls do, and why.

The mode selector (frequently incorporated into the input selectors of receivers) is hardly a new control facility; it is virtually as old as stereo FM. However, its function places it squarely within this category of control. The usual position for the selector is FM AUTO, and in this mode it switches the tuner's circuits automatically between stereo and mono according to what the program is.

Sometimes there is a STEREO ONLY position, in case you hate mono so much you can't stand to hear it even for the brief moment it takes to tune past a mono station (STEREO ONLY causes the tuner to pass up all mono stations).

Invariably an FM MONO position is also pro vided. This is not in case you hate stereo with equal fervor. Instead, the position is there to enable you to switch a weak and noisy stereo broadcast into mono for the purpose of reducing its noise. Combining the two channels of any stereo program source to create a mono signal will electrically cancel some of the noise components and result in a quieter presentation. And in the FM AUTO mode the tuner will in fact switch a hopelessly noisy stereo broadcast into mono automatically. The FM MONO mode gives the user a manual override of this automatic function. It is also useful when the strength of signal at the tuner input varies, causing the tuner to switch annoyingly back and forth between stereo and mono unless FM MONO is activated.

If switching a stereo signal to mono will eliminate a significant amount of noise, switching it only partially to mono should eliminate at least some noise. That is the principle of the high-frequency blend function. At a (presumably) modest sacrifice of the stereo effect, this switch is able to convert the pro gram to mono only over the range of the higher audible frequencies-frequencies at which the stereo noise content is generally fairly audible. A few multi-position blend switches are beginning to appear that will extend noise reduction (and stereo loss) somewhat down into the mid-range.

Muting (of the blast of noise that will otherwise be heard when you tune between stations) is a feature of virtually all high-fidelity tuners and receivers. On most units the muting can be switched off, enabling you to tune in very weak stations that would otherwise be silenced. The muting system's threshold is what determines how weak a station has to be before the tuner ignores it, and hence a vari able threshold (such as is available on some tuners) is a potentially useful feature. In general, the lower the threshold is set, the less effective the muting system will be, but the more stations the tuner will pick up with the muting switched in.

High selectivity is what a tuner has when it is able to reject interference occurring very close to the frequency to which it is tuned. Low distortion is what it tends to have when it will accept a wide band of frequencies above and below the nominal center frequency of the broadcast signal. Both characteristics are desirable, but beyond a certain point of design sophistication either one is achieved only at the expense of the other in current tuners. Usually it is the product's designer who decides the trade-off between these two parameters. But if the tuner has an i.f. bandwidth switch--as some deluxe units do--the user can take a hand in the compromise too. With the switch in the WIDE position the tuner favors low distortion at some moderate sacrifice of selectivity; the opposite is true for the NARROW position. Except under the most difficult reception conditions, WIDE would be the logical position of choice; but NARROW is there when audible interference requires it.

One of the components of a stereo FM (but not a mono FM) broadcast signal is a 19,000-Hz tone that will appear at the outputs of the tuner unless it is somehow removed. Since 19,000 Hz is within the audible range for some people (and within the reproduction range of some loudspeakers), and especially since a tone of this type will play havoc with many tape machines when they try to record from the tuner, eliminating this tone effectively has been a high-priority concern in stereo tuner design. The usual removing agent is the multiplex filter, which attempts to introduce a very steep cut-off slope above 15,000 Hz. But, of course, some filters are better than others, and the majority of them probably have some (slightly) audible "dulling" effect below 15,000 is happy about this situation, because there has recently come into existence a multiplex filter switch that will banish the filter at the punch of a button. Naturally this restores the 19-kHz whistle but, ears and loudspeakers being what they are, there is a good to excellent possibility that you won't be able to hear it. Presumably you will be able to hear a slight in crease in the program's high-frequency con tent. (It is very likely that tape recording will be impossible with most machines when the multiplex filter is switched out, however, and Dolby circuits, when used, will not work properly.)

No single tuner I know of has all the above features (in fact, I've encountered the multiplex filter switch only once, but who knows what will happen next month?). Probably some of the newer features will prove superfluous to most consumers and succumb to disuse in the marketplace. But it would be a shame if they disappeared merely because no one knew how or why to use them.

------

Also see:

TAPE TALK--Theoretical and practical tape problems solved.