Audio Careers

Q. I’m interested in getting a job in audio after. I get out of school. Are there special courses I should take or other things I should know?

A. MOORE; Philadelphia, Pa.

A. You'll probably find all the information you need in the twenty-one-page Guide to Careers in Audio Engineering published by the Audio Engineering Society. According to its introduction, the guide was prepared "to aid men and women who would like to know the nature of the audio profession, how they can become audio professionals, and what a career in audio would mean to them. The Guide suggests why such careers can be deeply satisfying to individuals of wide-ranging talents and interests. It describes the astonishing variety of fields open to the audio professional. For a copy, send $1 to Careers, Audio Engineering Society, Room 449SR, 60 East 42nd Street, New York, N.Y. 10017.

Dead Belts

Q. The service shop handling repairs on my ten-year-old tape deck sent me a note which read: "Rubber belts and tires dead from standing idle. To prolong belt life, recorder should be operated three or four hours per week." I thought this a strange comment. If true, what happens to new recorders kept in storage before sale?

AL Kois; Sacramento, Calif.

A. “Dead" was perhaps the wrong word to use; I think the correct expression would be that they had "taken a set." If a rubber belt under tension is stretched over its pulleys in one position for a long period of time, it could end up permanently deformed, which would probably increase wow and flutter. For a belt this is the equivalent of a flat spot on a rubber idler drive wheel (the "tire" referred to by your service shop).

I suspect that the materials used in the new drive belts are relatively immune to this sort of problem, but older machines that have seen long periods of disuse may indeed suffer from "dead" belts and rubber drive wheels.

Incidentally, anyone seeking a replacement belt, idler, or drive wheel for an old or new tape recorder (or record player) will probably find it listed in the very comprehensive thirty two-page reference catalog published by Projector-Recorder Belt Corp. (Dept. SR, 147 Whitewater Street, Box 176, Whitewater, Wisc. 53190). The catalog costs $1, which is refunded with the first order. And even if your cherished audio heirloom doesn't show up (along with Pentron and Magnecord) in the fine-print listings, all is not lost. The PRB Corporation offers to examine your old belt-if sent along with brand, model, and function in formation-and either supply a replacement from stock or make one up. Prices range from a low of $3 to a high of about $11.

Phono-input Gains

Q. I switch from phono 1 to phono 2 and vice versa on my amplifier, a noticeable difference in music loudness results.

Both turntables use the same model cartridge; however, the turntables themselves are different brands. I'd greatly appreciate a possible explanation for this difference in loudness.

JOE A. HURSON; Medford, Ore.

A. I'm not trying to do myself out of a job, but I suspect that you would have got ten a faster answer to your question if you had consulted the instruction manual of your amplifier! You would have found that when an amplifier (or receiver) has two magnetic phono inputs, their characteristics will frequently differ in some respect. The designer may choose to make one input "more sensitive." This means that a given signal level from a phono cartridge will be amplified more through one input, than through the other.

Since the more sensitive input usually has the smaller overload margin, by providing a choice of two sensitivities the manufacturer makes it possible to use a high-output phono cartridge with the low-sensitivity, low-gain in put and/or a low-output cartridge with the high-sensitivity, high-gain input. A low-output cartridge plugged into a low-sensitivity input will probably not play loud enough, and there may be excessive noise at the high volume-control setting that must be used. A high-output cartridge plugged into a high-sensitivity input will probably cause distortion of high-amplitude record signals. Of course, different gain characteristics do cause difficulty if you want to make rapid A-B comparisons between cartridges, but I suppose that most manufacturers didn't consider the making of such comparisons as the principal reason for having two phono inputs.

Adding Output Metering

Q. I've been wanting to add power-output or VU meters to my amplifier so as to get some idea what my equipment is putting out. Do you have any idea how I would go about connecting the meters?

ALAN PREIST; Denver, Colo.

A. Connection is easy; calibration is difficult. Any a.c.-responding voltmeter can serve as a power-output meter, but to cover the range of, say, 0.1 to 100 watts with an 8-ohm speaker load requires a meter that will indicate legibly over a scale of about 0.9 to 28 volts. Unfortunately, the below-5-watt area where most of the musical action occurs would be crowded into less than a quarter of the scale on such a meter. So, even if you could work out a point-by-point calibration correlation between watts and volts, you would still have the problem of severe scale cramping. In other words, if you simply want a meter needle to wiggle when your music plays, that's easy; if you want a meaningful numerical indication, that's another story.

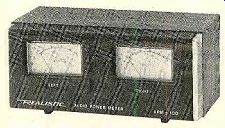

---The Radio Shack APM-100 audio power meter sells for about $20 and connects

directly across the speaker terminals. A switch sets calibration for 4- or

8-ohm speaker impedances.

I'm pleased to note, however, that Radio Shack has recently come up with a small, not-too-expensive product that solves such problems. As shown in the photo, it consists of two meters in a small plastic cabinet. Installation is simple: just connect the unit directly across the speaker terminals of each amplifier channel. No a.c. power source is needed. The meter impedances are high enough that neither the amplifier nor the speaker will know they are in the circuit. The meter scales are calibrated from 0.01 to 100 watts, and when I connected the unit across my rear-channel amplifier's speaker terminals they gave a reasonably accurate indication of the power delivered. The meters are heavily damped and tend to hold the peaks for easier reading.

Reel Static

Q. Recently, while rewinding my reel-to-reel machine, I turned the lights off and noticed static-electricity sparks around the reel. Could this disrupt the magnetic pattern on the tape? If it can, what should I do about it?

JEFF BURGESS; Louisa, Ky.

A. Visible static-electricity discharges occur when there is a large difference or imbalance in ionization between two adjacent substances. When the charges on the materials suddenly equalize each other, sparks are seen. An ion is an atom (or molecularly bound group of atoms) that has gained or lost electrons, thus producing a negative or positive charge. The ion transfer that puts a charge on a material takes place any time two insulating substances are rubbed together. The intensity of the charge depends mostly on the position of the two substances in the "triboelectric series" that lists various materials in order of their affinities for ions of one polarity or another. For example, if you are unwise enough to wear a rabbit-fur coat (very +) over a woven Teflon suit (very-) in a dry environment, the static-electricity charge created could reach tens of thousands of volts.

Obviously, recording tape, unless conductively back-coated, is an insulating material, and in its progress from the supply to the take-up reel it certainly does "rub" over various parts of the recorder. Visible discharges occur when the charge, instead of leaking off slowly, builds up to the point where it is strong enough to arc across an insulating gap of air. I don't think the arc is likely to damage your tapes or the signal on them, but, in any case, why not write to your recorder's manufacturer for his thoughts on the problem--if it is one? (The sparking might be susceptible to an easy fix such as Bounding or a change of lubricant.) In the meantime, if you were to sure that your recorder's static-electricity problem would quickly disappear.

Phono-cartridge Life

What is the life expectancy (in terms of usage or simply time) of a typical magnetic phono cartridge?

M. T. WALSH; Willoughby Hills, Ohio

A. I referred Mr. Walsh's letter to Frank Karlov, manager of electro-mechanical development at Shure Brothers, and here, in part, is his reply:

"The stylus-assembly parts that can be affected by use, misuse, and aging are the diamond tip, the stylus shank, and the elastomer bearing. The diamond tip is worn by playing records; the stylus shank can be bent or bro ken by handling accidents; and certain elastomer bearings can be affected by time, temperature, and various noxious components in the atmosphere. The elastomer material used by Shure, however, is not affected by long term storage or use." It seems clear that, with most cartridges, when you replace a stylus that has a worn diamond tip, then you are simultaneously replacing everything else that is likely to go bad with time. As far as the life of the diamond is concerned, it is very difficult to come up with a definitive number. Wear is determined by a complex of forces too numerous to go into here. Experts agree, however, that, considering all the variables involved, the stylus tip should be checked after every 100 hours or so of use by a reputable dealer.

------

Also see: