The key to buying is Power: How much do you want and how much do

you need?

Before you actually get down to the buying, you must have a clear idea not only of what you want but of what you need in terms of output power.

By George Tlamsa

FOR at least a dozen years, the receiver has been the most popular electronic high-fidelity component. Only recently has there been a revival of competition from the "separates"--tuners and amplifiers as separate units-that were once the only form in which hi-fi was readily available. The likeliest reasons for the receiver's original popularity were its relative compactness, its simplicity of installation, and (certainly not least) its economy. In addition, many people appreciated the fact that it reduced two or even three equipment choices (the separates approach) to one, thus reducing the number of life's difficult decisions.

But that was yesteryear. Times change, and the receiver has changed with them in many ways.

The number and variety of receivers available today is great, and so are the perplexities facing consumers who try to choose among them all. Furthermore, the receiver is no longer exclusively the physically and economically easy entry into high fidelity. There are units today whose size and weight prohibits their being mounted on anyone's bookshelf and whose cost may be well over $1,000. In respect to the usual performance specifications, the biggest and best receivers can match all but the most ambitious ensembles of separates point for point. But one of the best things about receivers-their economy remains much the same. Single-chassis construction and common power supplies provide inevitable cost benefits, and the very popularity of the component results in volume-production discounts.

And, as receiver specifications (at least for the more expensive units) increasingly find themselves in the same ball park as those of separates, the real distinction-cost aside-between the two product categories becomes more and more one of convenience. The receiver makes it possible to have an all-in one electronics center as opposed to the separates' flexibility in trading up and in obtaining repairs on one unit without shutting down the whole system.

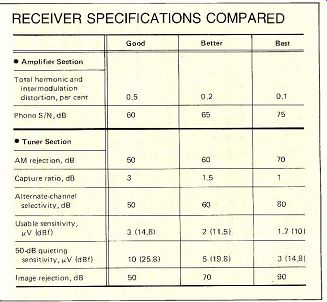

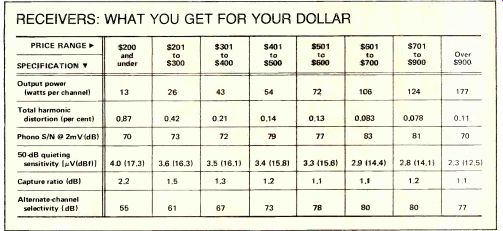

Of course, as the price of a receiver goes up, so does the level of its published specifications. To get an idea of what your dollar can buy, we will examine six common receiver specifications--three for the amplifier section and three for the FM section-and see how they correlate with price. The numbers given will be those quoted by the manufacturers rather than figures verified by independent test, but be assured that the figures quoted by today's name-brand manufacturers are to be trusted.

---------------

Amplifier Section

As a rule, the power-output rating of a receiver is the greatest single determinant of the unit's price: the more watts you want, the more money you pay. A complete power-output specification, as required by the Federal Trade Commission, includes the continuous per channel maximum in watts, the resistance or impedance to which this can be delivered (the "load") in ohms, the frequency range in hertz (Hz) over which the power is available, and the total harmonic distortion (at this power level) in per cent. A typical form for such disclosures is: "x watts per channel, minimum continuous (or rms) power output into y ohms from 20 to 20,000 Hz, with no more than z per cent total harmonic distortion." [The term "rms" in reference to power is used in correctly, but it is meant to be synonymous with "continuous power" meaning power that can be delivered continuously for an indefinite period, as opposed to some higher power level the receiver might be able to sustain for some brief period. The "load" is the impedance of the speaker (or the resistance of a resistor used to simulate the speaker in testing) to which the power is to be delivered. The most common load is 8 ohms, although 4-and even 16-ohm ratings occasionally appear. A 4-ohm rating will tend to be higher and a 16-ohm rating lower than the usual 8-ohm power specification.

Because power-output specifications-and the test procedures that verify them-are standardized by the FTC, you can compare the figures given for various makes and models of receiver with reasonable confidence. Of course, such comparisons won't help you much with the crucial question:

How much power will you actually need? For some discussion of this, see the accompanying box titled "How Much Power Do You Need?" as well as this month's "Audio Basics" (page 36). In the meantime, let's see just how much power your receiver dollar can buy in today's market. Keep in mind throughout that the prices given in this discussion are manufacturers' guidelines and do not reflect discounts that may be available from individual dealers.

Power and Dollars

At $200 and under you will find power output pretty low: the average is about 13 watts per channel, and in some cases the power (at the specified distortion rating) is not available over the full 20- to 20,000-Hz range. As you move into the $201 to $300 range (where there are a lot of units available-about forty) you'll find 26 watts per channel is average. In the $301 to $400 price class there is a significant jump to about 43 watts on the average.

The $401 to $500 class offers an aver age of 54 watts per channel, and the $501 to $600 class 72 watts per channel.

When you reach the $601 to $700 price range, you're getting into "super power" territory (for receivers, at least), with 106 watts per channel being the average rating. In the decidedly luxurious $701 to $900 range you get an average 124 watts and for over $900, 177 watts per channel. In the over-$900 category you will find receivers rated as high as 270 (!) watts per channel (the Pioneer SX-1980, for example, which has a "suggested value" of about $1,250).

Harmonic Distortion and S/N

Two other important specifications for the receiver's amplifier section are the harmonic-distortion rating, and the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of its phono preamplifier circuits. Let's look at distortion first. For $200 and under, the average harmonic distortion rating is about 0.87 per cent. Since receivers are commonly available with distortion well under one-tenth of this, what does such a figure mean? First of all, remember that the "rated distortion" is at full power output and that at moderate listening levels it will be much lower. Second, keep in mind that there is no agreed-upon standard for the audible threshold of amplifier distortion. Psychoacousticians, who deal with such matters, agree that distortion of about 0.35 to 1 percent be comes audible on certain program material, such as solo flute. However, actual listening tests have shown that, with much more complex music as the signal source, distortion can be as high as 6 per cent before it is noticed. The point is, don't be scared off by a "high" distortion rating of 0.87 per cent-you'll probably never hear it.

The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) in the $200-and-under category is 70 dB on the average. This is a thoroughly respectable figure, and with most speakers you would have to have your ears fairly close to the grille cloth to hear the hiss.

As a matter of fact, 70 dB is better than the S/N available on a lot of disc recordings and FM broadcasts.

In the $201 to $300 class, the average total-harmonic-distortion rating is about 0.42 percent and the S/N improves, on the average, to 73 dB. In the $301 to $400 price range distortion is 0.21 per cent on average and the S/N is unchanged. :n the $401 to $500 bracket, distortion averages 0.14 per cent and the S/N 79 dB. Distortion falls to 0.13 per cent on the average in the $501 to $600 class, with little or no change in average signal-to-noise ratio.

In the $601 to $700 price range the average distortion rating falls below 0.1 percent--to 0.083 per cent. The average signal-to-noise ratio improves to a high 83 dB. Between $701 and $900 you will find harmonic distortion averaging 0.078 per cent and S/N still in the low 80's. In the over-$900 range there is little or no significant improvement in these figures (S/N, in particular, being very close to its theoretical maximum), most of the increased cost going into power output. However, note that the figures given here are averages, and deviations for better and worse will be found in individual products.

Tuner Section

The tuner section of the receiver usually incorporating both AM and FM, though in some cases having FM only-has a large number of specifications associated with it. Three that are worth looking at closely are the 50-dB quieting sensitivity, the capture ratio, and the alternate-channel selectivity.

In general, the "sensitivity" of a tuner refers to the smallest possible input from the antenna required for a specific signal-to-noise ratio in the audio-output signal. Often you will see the "IHF us able sensitivity," which means the in put in microvolts (µN) or dBf necessary to achieve a S/N of 30 dB. In reality, this is too noisy to be very "us able" at all. The 50-dB quieting sensitivity is the input necessary to achieve a 50-dB SIN (or 50 dB of "quieting").

The lower this figure is, the better; any thing below 4 µV is good, and below 3.5 µV is excellent. Remember, though, that if you live in a city where you are close to the FM transmitters, sensitivity is not all that critical, but capture ratio may be.

A tuner's capture ratio is the smallest difference (in decibels) between the strengths of two broadcast signals of the same frequency at which the tuner is able to suppress the weaker one by 30 dB (that is, it "captures" the stronger). The capture-ratio rating is obviously important in areas (usually between two cities) where reception from two different stations broadcasting at similar or identical frequencies is possible.

It is also important in places where multipath distortion is a problem. Multipath occurs when two "competing" signals come from the same station, the direct signal as well as its delayed re flections (off buildings or other obstacles) meeting in your receiver and interfering with each other. The smaller the capture-ratio number the better.

Capture ratios of 1 dB are commonly quoted now, and this is close to the theoretical limit of performance. For some top-of-the-line FM tuners you will find capture ratios of less than 1 dB specified, although these are difficult to confirm repeatably under test. Keep in mind, however, that a good FM antenna can be a major factor in achieving hi-fi FM; if you have multi-path problems, a good directional antenna will be of more help than a fractional improvement in capture ratio.

The selectivity of a receiver is also of interest; it gives you some idea of how strong the signals on neighboring channels can be before they start to interfere seriously with the signal on the channel you're interested in listening to. Selectivity is given as the ratio (in decibels again) between the strength of the potentially interfering signal and that of the desired signal at the point where interference from the undesired signal is 30 dB below the desired signal's level. Whether the neighboring channel is adjacent (one channel away) or alternate (two channels away) makes a big difference; the commonly published specification is for alternate-channel selectivity, and the larger the figure the better. A common figure is 60 dB, and you will find values surpassing 90 dB in some higher-price receivers.

Quieting Sensitivity

In the $200-and-under price class, the 50-dB quieting sensitivity is 4 µV on the average. It improves quite a bit in the $201 to $300 range, where it averages 3.6 V. For the next $200 increment the average change is marginal: 3.5 µV in the $301 to $400 bracket and 3.4 µV in the $401 to $500 bracket.

There is another small improvement to 3.3 µ V in the $501 to $600 price range.

The average sensitivity is about 2.9µV within the $601 to $700 range, and in the $701 to $900 class the average is also 2.9 µV. In the over-$900 class, however, the 50-dB quieting sensitivity improves to a very low 2.3 uV on the average.

Capture Ratio

While the average 50-dB quieting sensitivity shows obvious improvement with increasing price, the capture ratio changes much less dramatically.

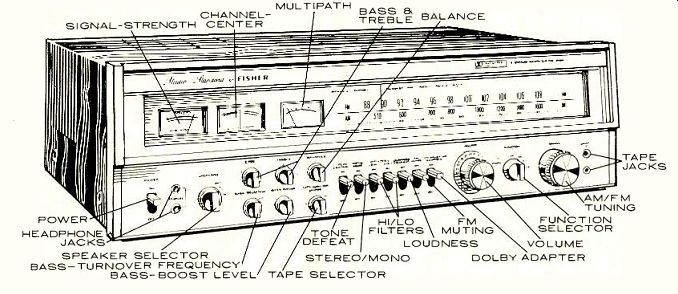

above: THIS MONTH'S COVER: A satisfied buyer poses with his new receiver acquisitions (top to bottom): Nikko NR-1415, Hitachi SR-2004, Kenwood KR-9600, Marantz 2500, Rotel RX-1603, and Pioneer SX-1980. At the frontispiece of this article is a Fisher unit.

In fact, in all but the lowest price class ($200 and under) the most commonly found value for this specification is 1 dB (which is excellent). The improvement of the average value with price is there, but it's slight. In the $200-and-under price class capture ratio is about 2.2 dB on the average; in the next four price ranges, spanning the interval be tween $201 and $600, the average cap ture ratios are about 1.5, 1.3, 1.2, and 1.1 dB, respectively. The average re mains at 1.1 dB for the $601 to $700 class, and changes very little at higher price points. Thus the capture ratio hovers at about the same value over the entire price spectrum, and its change with price does not appear to be very significant, at least as far as the manufacturers' quoted specifications are concerned.

Alternate-channel Selectivity

The alternate-channel selectivity does improve significantly with price.

At $200 and under it averages 55 dB, and it improves to about 61 dB in the $201 to $300 price class. In the $301 to $400 bracket there is a major improvement to an average of 67 dB, and in the $401 to $500 bracket there is another leap to an average of 73 dB. In the $501 to $600 class we're beginning to approach the upper limit (available on receivers, that is), with the average selectivity being about 78 dB. Average selectivity is 80 dB both in the $601 to $700 class and in the $701 to $900 class.

In the uppermost price range the most common figure is 80 dB.

Everything considered, it appears to be possible to get a receiver with excel lent overall specifications in both tuner and amplifier sections for between $200 and $300. As was mentioned earlier, what your money is primarily paying for (from the standpoint of specifications) is power output, which increases regularly with price. So try to keep all the other specifications in perspective as you make your buying decision. The difference between budget-price and state-of-the-art is not all that great in today's market. And remember that some manufacturers tend to rate their products more conservatively than others, so that in practice an apparent small difference in a quoted specification such as capture ratio may not really exist.

Operating Features

Of course, specifications are not the entire story for most purchasers. Operating features are also an important element, and as you go up in price you will find more and more features that make a receiver more flexible and easier to use. In fact, on some of today's state of-the-art receivers it is possible to find exotic control features that were avail able only on high-price separates (if on those) not too long ago.

For $200 and under, you generally get only the most basic features and controls. Receivers priced at this level have a single tuning meter (these days usually a channel-center meter, but sometimes a relative-signal-strength indicator), simple bass and treble tone controls, and provision for connecting one record player and one tape ma chine. One feature that is sometimes found here (and at higher price levels) is microphone mixing: this feature consists of a front-panel jack for a high-impedance microphone along with a control for mixing the microphone with the other inputs. Most $200-and-under low-power receivers can comfortably drive only one pair of speakers at a time and therefore don't provide for speaker switching.

----------------------

HOW MUCH POWER DO YOU NEED?

ROOM VOLUME (CUBIC FEET)

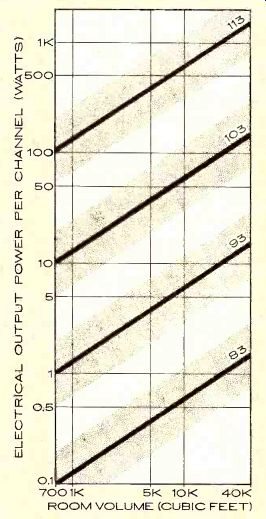

Power vs. room-volume curves for an inefficient speaker (82 db/W/m).

The shaded area around each line shows a range of uncertainty in the power values.

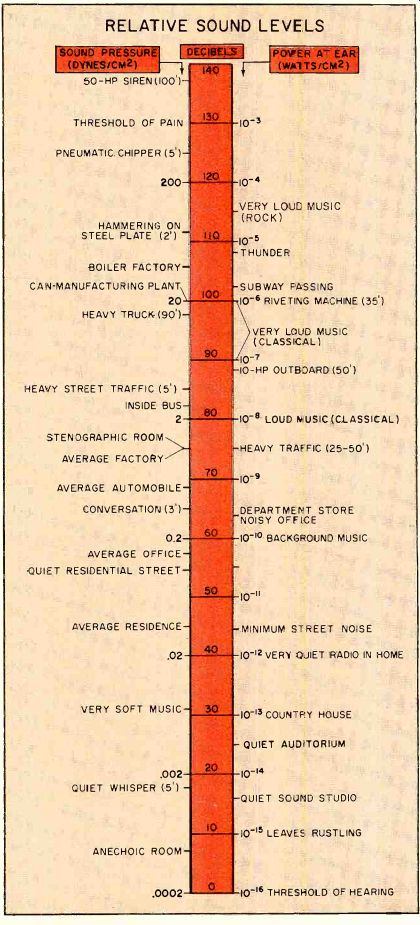

AMPLIFIER power costs money, so it's worth considering just how many watts you'll really need from your receiver. To understand the factors involved, you should understand how the human ear perceives loudness--and how amplifier power output relates to that. In de scribing sound levels we generally use the decibel (dB). In music, the smallest level change readily audible to anyone with normal hearing is about 3 dB, and a 3-dB change in sound level always results in about the same subjective loudness change, regardless of whether the change is from 70 to 73 dB or 90 to 93 dB. How ever, small as such a change is to the ear, it is substantial in respect to demands on the amplifier.

To increase a sound level by 3 dB means doubling the amplifier power output--and a 10-dB increase means multiplying the power by ten (it's logarithmic). Some peaks in recorded music are likely to ask your amplifier for a sudden 15- or even 20-dB in crease in sound level for a short but significant period of time--in other words, up to a hundred-fold increase in amplifier output. Although the problem is not as severe as it may appear at first glance (since the average power used may be no more than 3 or 4 watts), it is easy to drive an amplifier into "clipping" by trying to get more power out of it than it is capable of delivering.

How much loudness you get out of your speakers for the watts you put into them is affected by several factors, including the characteristics of your listening room. The internal surfaces of a room tend to contain the sound and reflect it to the listener.

Therefore, sound levels do not fall off at a precipitous rate with every step you take away from the speaker (as they would in the open air). How well your room reflects--whether it has many sound-absorbing surfaces, in other words--will make a big difference. So will the physical size of the room. If you have a "live" room with a lot of reflective surfaces, you'll need considerably less power than if you have a "dead" room with heavy carpeting, overstuffed couches, soft armchairs, and so forth. But keeping the room "live" to reduce the power demands made on the amplifier is not the way to go, be cause the music will sound raucous, shrill, and echo-y.

The efficiency of your speakers is the important factor. If it takes a large power input for the speakers to produce a given sound level, you've got "inefficient" speakers, and you'll need more power than someone with "efficient" speakers that produce a large output for the same input power. Speaker efficiency is often given in the form of "sensitivity" ratings which state the sound output of the speaker (measured at a 1-meter distance) when driven by 1 watt of power by the amplifier. Using this sys tem, 82 dB per watt per meter (dB/W/m) is decidedly inefficient; 93 dB/W/m is comparatively efficient.

Many speakers available today produce in the neighborhood of 90 dB at 1 meter for a 1-watt input.

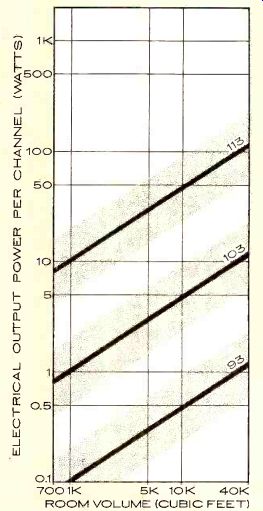

THE accompanying graphs will help you establish (very approximately) your power needs. They show the electrical output power required per channel as a function of room volume for various sound-pressure levels: 83, 93, 103, and 113 dB ("soft" to "very loud"). There are curves for an efficient speaker (93 dB/W/m) and an inefficient speaker (82 dB/W/m).

Note the large difference in power required by these two types of speaker.

For example, the power required by the efficient speaker for 83 dB is too small to be shown on the graph (it is below 0.1 watt).

These curves are based on rooms with proportions of about 1:1 1/2:2 (height: width: length) and with an "average" reverberance (not too live and not too dead). They also assume that the listener is positioned about 10 feet from the speaker. To use the graph, first find the volume of your room in cubic feet on the horizontal axis and then travel up (vertical axis) until you reach the bar corresponding to the sound level you hope to achieve. Then travel horizontally along that bar to the left-hand vertical axis to read the range of powers in watts likely to be required. For example, to achieve a level of 100 dB in a room of 20,000 cubic feet with the efficient speaker will probably re quire anywhere from 3 to 12 watts. In practice it could require even more (or Less), depending on such factors as the absorptive qualities of the room and its furnishings, the location, configuration, and directional characteristics of the speaker, and may others (see this month's "Audio Basics" for further observations on this subject).

FOR speakers whose efficiencies do not correspond to the two examples given, approximate solutions can be found by transposing the bars over a 2:1 power ratio for each 3 dB of difference. For example, a speaker rat ed at 90 dB/W/m would theoretically require between 6 and 24 watts to achieve a 100-dB level-twice what the more efficient speaker would need. A rating of 87 dB/W/m would mean 12 to 48 watts. Considering the great variations likely to be introduced by real rooms and real speakers, it is probably not worth trying to estimate your power requirements any closer than to the nearest 3-dB increment.

------------ Power vs. room-volume curves for an efficient speaker (93

db/W/m). The shad ed area around each line represents a range of uncertainty

in the power values.

-----------------------------------

Between $201 and $300, the number of features available does not change very much overall; most of the improvement, as noted above, is in the area of specifications, and this improvement is quite great. You will find two tuning meters virtually standard here. Low- and high-frequency filters-if of dubious effectiveness become fairly common also (they are available on some receivers in the below-$200 price class, but not many).

As you move into the $301 to $400 price range, features really begin to appear. Tone controls are more flexible, and a number of units offer mid-range controls in addition to bass and treble;

some have only bass and treble controls but have separate controls for each channel. Marantz, in its receivers from $310 up, has mid-range controls as well as separate controls for each channel. Some receivers in this price range have detented potentiometers for their volume controls instead of the conventional pots (this feature becomes quite common in the higher price brackets). Audio muting controls, which attenuate the receiver's output for brief listening interruptions, also begin to appear. Yamaha's CR-620 ($350) permits you to adjust the volume level and the loudness compensation separately. Tape facilities are more flexible, with a good many receivers accommodating two tape decks and permitting dubbing from either one of them to the other.

The most noticeable addition to tuner facilities is the appearance of an "FM de-emphasis" switch on the front panel; this permits you to change the tuner's de-emphasis from 75 to 25 microseconds so it can, in conjunction with a Dolby processor, properly de code Dolby-FM broadcasts. And, for

$350, Sony's STR-4800SD provides you with a built-in Dolby processor.

There are a few other tuner niceties.

For example, Akai's AA-1150 ($400) has a control for adjusting the tuner's noise-muting level. This lets you set the level at which the tuner rejects the interstation noise but not weak stations. Many receivers have an FM muting switch, which merely defeats the This chart gives an idea of the subjective "loudness" of different sound-pressure levels in terms of everyday sounds. Note the wide range of levels the ear responds to tuner's interstation-noise muting circuits. One other interesting feature available in this price class is the totally separate power supplies for the two channels in Harman Kardon's 430 ($280).

------------ RELATIVE SOUND LEVELS SOUND PRESSURE (DYNES/CM^2)

--------------------

Between $401 and $500 you can find receivers with fairly exotic tone controls. Consider JVC's JR-S300II ($430), which has a full five-band equalizer with slider controls (it also has power meters). You also begin to find receivers that have switchable turnover frequencies for their tone controls, such as Fisher's RS-1056 ($450). Along with this comes the appearance of "tone de feat" switches that permit you to switch the tone controls completely out of the signal path.

A NUMBER of receivers in the $401 to $500 bracket have two (separate) tape-monitor circuits. This is a handy feature, since you can not only control two tape decks but also use one monitor circuit to handle an equalizer or other accessory. Onkyo's TX-4500 ($480) has switching for three tape decks. Optonica offers an interesting tape feature on its SA-4141 ($430): a test tone for setting the levels on your recorder be fore taping an FM broadcast. The Rotel RX-7707 ($480) and the Tandberg TR-2025 ($465) permit you to preset up to five FM stations and later tune them in (electronically) at the touch of a but ton. One other convenient feature that becomes more common in this price bracket: inputs for two record players.

By the time you reach the $501 to $600 class, there aren't too many basic features available that you can't find for less money, but there are a few: receivers in this price class are more likely, for example, to have switching for as many as three pairs of speakers. You will notice more receivers with preamp-out/power-amp-in jacks on their rear panels, and this is certainly a plus; not only does it permit you to connect a signal processor into the signal path, but it makes your all-in-one receiver a bit more flexible, as you can now use its preamp/tuner and power amp separately. You will find quite a few receivers here that have provisions for plug in Dolby decoder modules as well.

"Tape-through" switching circuits become common in this price class (though this feature is also available in the $350 Yamaha CR-620); these permit you to dub from one tape deck to another while using the receiver to play a third program source. Power-output meters are quite common too, and some receivers even have switchable meter ranges. High- and low-frequency filters become more sophisticated, with Yamaha offering switchable turnover frequencies on its CR-1020 for $560.

The filters provided on the more expensive receivers usually have sharp "slopes" (expressed in decibels per octave); the slope of a filter tells you how rapidly it attenuates signal level with frequency. In the realm of FM, you can get a digital tuner readout on Heath's AR-1515 (kit price: $580).

As you go beyond $600, you will find all sorts of special features, many of which are downright luxurious. Some receivers, like Rotel's RX-1203 ($750), offer controls for adjusting .the phono input sensitivity and impedance (the former feature is useful for setting the gain of the input stage of the phono preamplifier to achieve maximum signal-to-noise ratio). Yamaha's CR-2020 ($750) even has a high-sensitivity pho no input for a moving-coil cartridge.

Interesting tuner features abound as well, with some manufacturers offering sophisticated tuning aids: Rotel has multipath meters on its RX-1203 and 1603 ($840 and $1,100, respectively) and Marantz goes so far as to include an oscilloscope on the front panel of its model 2500 (for $1,850), this being the best means of monitoring multipath distortion. Some receivers have a hi-blend feature, which is used to reduce the audible hiss that accompanies weak stations. Nikko even offers switchable i.f. bandwidth on its NR-1415 ($850), giving you the option of achieving better selectivity at the cost of a bit more "conventional" distortion. If you'd like to use your receiver for short wave or other non-commercial-band broad casts, check Tandberg's TR-2025MB multiband receiver ($665).

Other niceties include LED power indicators (which can be set to read peak as well as average power), as on the Lux R-1120 ($895), and front-panel warning LED's that indicate amplifier overload, as on the Setton RS-660 ($880). Where price is no object you will find a number of receivers that are not only endowed with a full array of features but also very distinctively styled. Bang and Olufsen's Beomaster 4400 ($695) is a good example of this, having a novel front-panel design and featuring electronic touch-contact switches-switches that require merely the touch of a finger to be activated.

------------ RECEIVER SPECIFICATIONS COMPARED

---------- RECEIVERS: WHAT YOU GET FOR YOUR DOLLAR

Overall, it appears that useful special features really begin to show up on receivers priced at over $300. In the $300 to $500 price range there is a dramatic improvement in the number and useful ness of such features. For below $300 (and even for $200 and under) it is possible to get a very serviceable receiver; it will, however, have only the most basic operating controls (which are all many people ever use) and, as we said earlier, it will have a modest power out put. For over $500 you find lots of extra features and output power-and a strict application of the law of diminishing returns as well. As you go up in $100 increments you are getting ever smaller increments of improvement; the "performance improvement per dollar" is not as great at the high price points as in the below-$500 bracket.

One other aspect of the receiver market merits discussion at this point: four-channel. At this time, while the FCC is considering the question of standards for quadraphonic FM broad casts, a lot of audiophiles are wondering whether four-channel is dead. You might be interested to know that there are still some quadraphonic receivers available, and there are many more stereo receivers with either four-channel adaptability or some form of synthesis. Sansui and Pioneer both have four-channel receiver offerings. The Sansui units, models QRX-9001 ($1,100) and QRX-8001 ($900) deliver 60 and 40 watts per channel (four channels driven), respectively. Pioneer's QX-949A ($750) is rated at 40 watts per channel, four channels driven. A variety of four-channel-simulation circuits is also offered in the stereo receivers of several manufacturers (among them Lafayette, Realistic, Superscope, and Sherwood). Sherwood offers a special tape-monitor circuit for a four-channel adapter on its S-9910 ($700), and all Marantz receivers have jacks for a four-channel adapter.

Buying

Before you actually get down to the buying of your receiver, you must have a clear idea not only of what you want but of what you need in terms of output power. Approximating your power requirements will all by itself trim the field down to a relatively small and therefore manageable price spread. After that basic step, determine what features you must have-assuming some special features are important to you.

Also, if you are cramped for space or move frequently, it would be a good idea to check carefully the dimensions and weights of whatever units interest you; today's higher-power receivers can be very large and heavy.

If you follow through on these at home preliminaries, you'll narrow your choice enough to cut down substantially on your shopping time. Though a listening test in the store can't tell you too much about a receiver's total performance capabilities, it will permit you to get to know the product, its appearance, flexibility, and "feel." Keep in mind that the prices quoted in this article are "nationally advertised values." In many cases they will be higher than the price you actually end up paying. Obviously the discounting policy of every retailer is likely to be different. But remember that maximum discount usually goes hand-in-hand with minimum after-sale service.

And finally, though this is not a how to-buy-a-speaker article, we would be doing less than our duty if we didn't warn you about the "system-package" ploy used by some dealers. These systems usually include a name-brand receiver and a no-name or house-brand pair of speakers. The "package price" usually offers an apparently enormous discount on all the components, but in truth the discount is large only on the receiver. The dealer makes his profit on the house-brand speakers, which are usually priced with an excessively high markup. The result is that the consumer, believing he is getting a fantastic discount, buys a top-quality receiver to be played and heard through mediocre-or worse-speakers.

AFTERWORD

WE have not discussed many of the proprietary circuit features or the special design approaches used in receivers since we are not in a position to evaluate the practical significance of such features without extensive laboratory and/or use tests. When Julian Hirsch per forms such tests they usually appear as a laboratory report in STEREO RE VIEW. An index listing the receivers (and all other, products) tested since 1965 is available for 25 cents / and a stamped, self-addressed long envelope. Write:

STEREO REVIEW, Dept. TRI, One Park Ave., New York, N.Y. 10016.

Although we have not tested most of the receivers now on the market, those that we have tested give us confidence in the component as a category. While it is al ways possible to pick nits with any product, we are pleased to be able to report that it is really very difficult to make a wrong decision in receivers these days.

--------

GLOSSARY OF RECEIVER TERMINOLOGY

AM suppression: a measure of how successful an FM tuner section is in suppressing the noise-producing amplitude variations in the incoming signal. A high figure (in decibels) is desirable.

Amplifier section: the part of a receiver devoted to accepting the in puts of the various program sources, adjusting them in level and tonal characteristics by means of designated front-panel controls, and amplifying them for the loudspeakers.

Capture ratio: the difference in strength between two incoming FM signals of the same frequency that is necessary if a receiver is to "cap ture" the stronger and reject the weaker. A low figure (in decibels) is desirable.

De-emphasis: the equalization introduced by an FM tuner section for proper reproduction of an FM broad cast which has been pre-emphasized by the broadcaster in a complementary way. The U.S. has two FM equalization characteristics in regular use:

75 u-sec (microseconds) for standard broadcasts and 25 u-sec for Dolbyized transmissions. Many receivers provide both.

Dolby system: a dynamic noise-reduction system employed in some tape machines (particularly cassette machines) and some FM broadcasts.

Proper reproduction of Dolbyized broadcasts requires a Dolby processor and a different tuner de-emphasis characteristic (see above).

Distortion: spurious additions made by a receiver to a signal it is processing. Two types of distortion are regularly specified: total harmonic distortion (THD) and intermodulation distortion (IM).

Equalization: deliberate frequency-response manipulation of a re corded or broadcast signal, usually intended to improve its signal-to noise ratio. Special circuits within a receiver "undo" the equalization to restore flat frequency response while retaining the signal-to-noise benefits.

Filters: switchable circuits that re duce the level of low and /or high frequencies to subdue noise such as rumble or record-surface noise. A 6-dB-per-octave filter is barely worth while; a 12-dB-per-octave filter is preferred.

Frequency response: a specification indicating the frequency range over which a receiver has useful out put, as well as the degree of deviation from absolute uniformity tolerated over that range.

Interstation-noise muting: a circuit (often switchable) that automatically silences the output of an FM-tuner section when it is between stations, thereby eliminating interstation noise. An audio muting switch, found on many receivers, simply reduces the output of a receiver by a large amount to accommodate brief listening interruptions such as telephone calls.

Loudness compensation: a circuit that works in conjunction with a receiver's (or amplifier's) volume control to boost low (and sometimes high) frequencies progressively as volume is reduced. The intent is to compensate for the ear's normal loss of sensitivity to these frequencies at low listening levels.

Multipath: an undesirable condition in FM radio reception arising when the same signal reaches the receiving antenna via different "paths." The interference of these signals at the antenna imparts a fuzzy or rasping quality to the sound.

Selectivity: a measure of how much stronger than the desired station another station broadcasting on a nearby frequency can be before significant interference takes place.

Sensitivity: measures a tuner's ability to provide a quiet, undistorted output from a weak signal input.

There are two sensitivity specifications for FM: usable sensitivity (the minimum signal strength, in dBf or microvolts, necessary for the signal to be 30 dB stronger than the noise and distortion) and 50-dB quieting sensitivity (the minimum signal necessary for a 50-dB signal-to-noise ratio).

Signal-to-noise ratio: indicates to what degree noise (hiss and hum) is below the receiver's maximum signal level (a S/N of 80 dB means that noise is 80 dB below the signal).

Spurious-response rejection: the ability to reject a variety of signals that are generally distant in frequency from the station to which the tuner section is set. (Image rejection and i.f. rejection are both facets of spurious-response rejection).

Tape monitor: a switch-activated circuit that permits comparison of a tape an instant after it is recorded with the original signal going onto the tape. A three-head tape machine is required.

Tuner section: accepts FM (and often AM) signals from the antenna, demodulates them (turns them into audio), and generally puts them into a form suitable to be processed by the receiver's amplifier section.

-----------------

Also see:

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)