PART ONE: Understanding Television's Structures and Systems

Television's Ebb and Flow

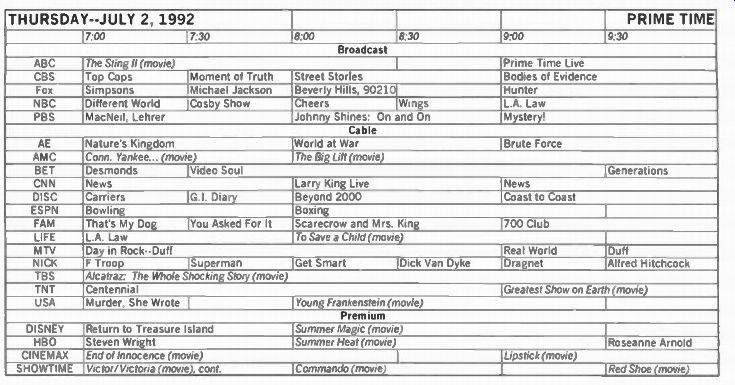

Newspapers and magazines that list television programs often use a grid to represent an evening's schedule. In many of them, the channels run vertically down the left side of the grid, while half-hour time "slots" run horizontally along the top. (Fig. 1 shows one such grid for a summer day in the 1990s.) The reasoning behind this array is obvious. At a glance, we can fix our location in the grid, noting the axis of channel (say, channel 9) and the axis of time (say, 7:00). After figuring that location, we can quickly see what will follow the current program in time (horizontal) and what is happening on other channels at that same time (vertical). Grids such as these may help us understand the basic structure of TV and the experience of watching television. Most listings emphasize programming time slots rather than the individual programs themselves. TV Guide, with a few exceptions, does not describe TV programs separately from their time slots.

Only movies on "premium" cable channels (HBO, Showtime, Disney, and so on) receive special status in this regard.' In addition to noting movies in the listings grid, TV Guide isolates them from other television programs and indexes them, film by film, in the back of each issue. There is no corresponding index for any other type of television program. The editors of TV Guide evidently believe that viewers experience movies differently from other television programs.

The grid in Figure 1 and TV Guide's format illustrate that television pro grams are positioned by network programmers and experienced by viewers as one program within a sequence of other programs in an ongoing series of timed segments. Further, programs are also associated-potentially linked- with other programs by their shared time slot. During the time that a television set is on in U.S. households-7i hours per day, on average-we are carried along in the horizontal current of television time, flowing from one bit of TV to the next. Equally important, we may move vertically from one channel to another, creating associations between concurrent programs. A listing grid depicts visually these two axes of television's structure: sequence (one thing after another) and association (connections among simultaneous programs).

FIGURE 1

We begin with this brief consideration of program listings because it illustrates the fundamental principle of commercial television's structure. As Raymond Williams first argued in 1974, television differs crucially from other art forms in its blending of disparate units of narrative, information, and advertising into a never-ending flow of television.' Although we commonly talk of watching a single television program as if it were a discrete entity, more commonly we simply watch television. The set is on. Programs, advertisements, and announcements come and go (horizontal axis). Mere fragments of programs, advertisements, and announcements flash by as we switch channels (vertical axis). We stay on the couch, drawn into the virtually ceaseless flow. We watch television more than we seek a specific television program.

The maintenance of tele-visual flow dominates nearly every aspect of television's structures and systems. It determines how stories will be told, how advertisements will be constructed, and even how television's visuals will be designed. Every section of this guide will account in one way or another for the consequences of tele-visual flow. Before we start, however, we need to note three of this principle's general ramifications:

1. Polysemy

2. Interruption

3. Segmentation

POLYSEMY, HETEROGENEITY, CONTRADICTION

Many critics of television presume that it speaks with a single voice, that it broadcasts meanings from a single perspective. During the 1992 presidential election campaign, Vice President Dan Quayle singled out the TV pregnancy of an unwed mother--Murphy Brown (Candice Bergen )-as indicative of television's assault on "family values" (a euphemism for a conservative ideology of the family). For Quayle, the meanings presented on TV had systematically and univocally undermined the idea of the conventional nuclear family: father, mother, and correct number of children; the father working and the mother caring for children in the home; and no divorce or single parenthood. Television's discourse on the family had become too liberal-even decadent-according to Quayle and his supporters.

What Quayle failed to take into consideration, however, is the almost over whelming flow of programs on television. Murphy Brown (1988-1998) is but one show among the hundreds that compose TV flow. And its endorsement of single parenthood, if such indeed is the case, is just one meaning that bobs along in the deluge of meanings flooding from the TV set. The many meanings, or polysemy, that television offers may be illustrated by excerpting a chunk of the television flow. Look at the Thursday-night schedule reproduced in Fig. 1.

Let's presume that a typical viewer might have watched The Simpsons, followed by The Cosby Show, then taken some time off to put the kids to bed, and concluded the evening with Roseanne Arnold, departing from broadcast network television for this HBO specia1.3 (Of course, this doesn't even take into consideration the channel switching that might have gone on during a particular program; but for the sake of illustration, we'll keep it simple.) What meanings surrounding the U.S. family, we might ask, do these three programs present? TV Guide describes Roseanne Arnold, the special: "The comedienne comments on women's rights and dysfunctional families in stand-up?' Roseanne, in some respects, exemplifies Quayle's comments. Her publicly available private life, frequently represented in television "magazine" programs such as Entertainment Tonight, illustrates the decay of the conventional family: her acrimonious divorces, her pregnancy while unmarried (and the child she gave up for adoption), her allegation of abuse as a child, and so on. In this special, she describes her family: There's Dad in his greasy T-shirt slopping down a beer and eating a big bowl of Capen Crunch. Mom's passed out on the couch while her horrible little dog licks her sweaty feet. My brother's dressing up like a girl, my sister's dressing up like a guy. I'm stealing food out of the fridge hand over fist, while my younger sister, who weighs all of 80 pounds, is upstairs doing jumping jacks for two hours 'cause she just ate a whole can of green beans and thinks she's too fat.

Thus, one meaning connoted by Roseanne Arnold, the program-and even Roseanne, the person-is that the traditional family is disintegrating, dysfunctional, and oppressive.

As a premium cable service, HBO promotes itself as providing material that is not seen on broadcast television. HBO's programs contain violent and sexual material forbidden by broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC, UPN, and WB). It would be misleading, therefore, to assume that Roseanne Arnold typifies television's representation of the family. For that we must look to The Cosby Show and The Simpsons.

On The Cosby Show the traditional family is far from disintegrating, dysfunctional, or oppressive. Quite the contrary, The Cosby Show illustrates the strengths of the nuclear family--not surprising, considering that producer Bill Cosby has a doctorate in education and uses the program to propound his approach to child rearing. There may be occasional friction within The Cosby Show's family (the Huxtables), but in the final analysis it provides an enclave, a safety zone, of affection and nurturing. In the episode rerun on our sample Thursday, the Huxtables' married daughter, her husband, and their twins are moving out of the Huxtable house. This allows for some joking by the father, Cliff (Bill Cosby), about his pleasure in getting rid of his daughter, but the centerpiece of the episode is a scene in which Cliff babysits the twins alone.

This scene reinforces Cliff's skill with children (echoed in Cosby's commercial work for Jell-O) and emphasizes the importance of the (grand)parent-child relationship. In short, Cliff and Clair Huxtable signify all that is positive about the conventional family structure.

Are Quayle's "family values" associated with our final example, The Simpsons? Yes and no. The Simpsons exists somewhere in the middle of the spectrum that places The Cosby Show on one end and Roseanne Arnold on the other. The Simpsons does chip away at some of the foundations of the conventional family, but in the end it comes to reaffirm those foundations. Homer Simpson, for instance, is a much less satisfactory father figure than is Cliff Huxtable. On this particular Thursday, the Simpson family faces a crisis: The dog is sick and re quires a costly operation to survive. Homer's response-typically ungenerous and self-serving-is to tell the children about "doggie heaven" and prepare to put the dog to sleep. Obviously, this is not the behavior of a caring patriarch such as Cliff. After Marge Simpson (a rather conventional mother figure, except for her towering blue hairdo) calculates a plan to finance the operation, Homer finally agrees to it, muttering, "lousy manipulative dog." By the end of the episode, the Simpson family--Homer included--has rallied around the dog, drawing close, as sitcom families always have. The "family value" of the supportive clan with the nurturing mother is reasserted.

As this small portion of the televisual flow illustrates, television contradicts itself frequently and haphazardly. It presents many heterogeneous meanings in any one night's viewing. This polysemy contributes to television's broad appeal.

With so many different meanings being signified, we are bound to find some that agree with our world view. Does this mean that television can mean anything to anyone? And how are these meanings constructed? Three axioms will guide our approach to television.

Axiom 1. A segment of the televisual flow, whether it be an individual program, a commercial, a newscast, or an entire evening's viewing, may be thought of as a televisual text-offering a multiplicity of meanings or polysemy. When Roseanne describes her family, her words signify, among other things, "my family was dysfunctional”. In its broadest sense, a "text" is any phenomenon that pulls together elements that have meaning for readers, viewers, or spectators that encounter it. Just as we read and interpret a guide's organization of words in sentences, so we view and interpret a television program's sequence of sounds and images. Thus, narrative and non-narrative structures, lighting and set design, camera style, editing, and sound may be thought of as television's textual elements-those basic building blocks that the makers of television use to communicate with their audience. This guide will present ways for students to better understand how these textual devices mount potential meanings for the viewer's consideration.

Axiom 2. The television text does not present all meanings equally positive or strong. Through dialogue, acting styles, music, and other attributes of the text, television emphasizes some meanings and de-emphasizes others.

When the Simpson family gathers around their dog, with smiles on their faces and upbeat music in the background, the text is obviously suggesting that family togetherness and sacrificing for pets are positive meanings. But although television is polysemic, not all meanings are equal. TV is not unstructured or infinitely meaningful. Or, as John Fiske writes, "[Television's] polysemic potential is neither boundless nor structureless: the text delineates the terrain within which meanings may be made or proffers some meanings more than others." The crucial work of television criticism is to analyze the medium's hierarchy of meanings. Which meanings does the text stress? How are they stressed? These are key questions for the television critic. To answer them requires an awareness of the cultural codes of class, gender, race, and such, that predominate a society. As Stuart Hall has noted, "Any society/culture tends, with varying degrees of closure, to impose its classifications of the social and cultural and political world. This constitutes a dominant cultural order, though it is neither univocal nor uncontested." Television always has been a medium encoded with the meanings prevalent in the society to which it appeals. In contemporary U.S. society, many meanings circulate, but some are given greater weight than are others by the dominant cultural order. Correspondingly, although television is polysemic, it must be stressed that it is a structured polysemy. There is a pattern or structure implicit in the meanings that are offered on television.

That structure tends to support those who hold positions of economic and political power in a particular society, but there is always room for contrary meanings.

Axiom 3. The act of viewing television is one in which the discourses of the viewer encounter those of the text. A discourse, in this sense of the term, has been defined by Fiske as "a language or system of representation that has developed socially in order to make and circulate a coherent set of meanings about an important topic area. These meanings serve the interests of that section of society within which the discourse originates and which works ideologically to naturalize those meanings into common sense."' We come to a TV text with belief structures-discourses-shaped by our psyche and social position: schooling, religion, upbringing, class, gender. And the TV text, too, has meaning structures that are governed by ideology and television-specific conventions. When we read the text, our discourses overlay those of the text.

Sometimes they fit well, and sometimes they don't.

Discourses do not advertize themselves as such. The dominant discourse is so pervasive that, as Fiske suggests, it disappears into common sense, into the taken-for-granted. Consider the common presumption that in the U.S. everyone can become financially successful if they work hard. Most Americans believe this to be a truth, just common sense-despite the fact that statistics show that the economic class and education level of your parents virtually guarantees whether or not you'll succeed financially. The notion of success for all, thus, has a rather tenuous connection to the real world of work. However, it has a very strong connection to the discourse of corporate capitalism. If workers, even very poor workers, believe they may succeed if they work hard, then they will struggle to do good work and not dispute the basic economic system. So we may see that the commonsensical "truth" of the Horatio Alger success story is a fundamental part of a dominant discourse. As critics of television, it is our responsibility to examine these normally unexamined ideals.

INTERRUPTION AND SEQUENCE

Up to now we have depicted television as a continuous flow of sounds and images and meanings, but it is equally important to recognize the discontinuous component of TV watching and of TV itself-the ebb to its flow.

On the Thursday-night grid in Fig. 1, we can move horizontally across the page and see, obviously, that an evening's schedule is interrupted every half-hour or hour with different programs. One program's progression is halted by the next program, which is halted by the next, and the next. Within pro grams the flow is frequently interrupted by advertisements and announcements and the like. And on an even smaller level, within narrative programs' story lines there tend to be many interruptions. Soap operas, for example, often present scenes in which characters are interrupted just as they are about to commit murder, discover their true paternity, or consummate a romance that has been developing for years.

The point is that TV is constantly interrupting itself. Although the flow that gushes from our TVs is continuously television texts, it is not continuously the same type of texts. There are narrative texts and non-narrative texts and texts of advertising and information and advice, and on and on it goes.

Furthermore, we as viewers often interrupt ourselves while watching television. We leave the viewing area to visit the kitchen or the bathroom. Our attention drifts as we talk on the phone or argue with friends and family. We doze. And remote-controlled TV sets permit the most radical interruption of all: random channel switching. With a remote control, we choose the speed of interruption and move along the vertical axis of the grid, creating a mosaic of the texts that are broadcast concurrently. We blend together narrative and non-narrative programs, movies, advertisements, announcements, and credit sequences into a cacophonous super-text-making for some occasionally bizarre juxtapositions (as we switch, say, from a religious sermon to a rap video). The pace can be dizzying, especially for other viewers in the room who are not themselves punching the remote's buttons.

All of these forms of interruption--from television's self-interruptions to the interruptions we perform while watching-are not a perversion of the TV viewing experience. Rather, they define that experience. This is not to suggest, however, that television does not try to combat the breaks in its flow. Clearly, advertisers and networks want viewers to overcome television's fragmentary nature and continue watching their particular commercials/programs. To this end, story lines, music, visual design, and dialogue must maintain our attention, to hold us through the commercial breaks, to quell the desire to check out another channel.

SEGMENTATION

Television's discontinuous nature has led to a particular way of packaging narrative, informational, and commercial material. The overall flow of television is segmented into small parcels, which often bear little logical connection to one another. A shampoo commercial might follow a Seinfeld scene and lead into a station identification. One segment of television does not necessarily link with the next, in a chain of cause and effect. In Fiske's view, " [Television] is composed of a rapid succession of compressed, vivid segments where the principle of logic and cause and effect is subordinated to that of association and consequence to sequence." That is, fairly random association and sequence-rather than cause and effect and consequence-govern TV's flow.

TV's segmental nature peaks in the 30-second (and shorter) advertisement, but it is evident in all types of programs. News programs are compartmentalized into news, weather, and sports segments, then further subdivided into individual 90-second (and shorter) packages or stories. Game shows play rounds of a fixed, brief duration. MTV comprises mostly individual music videos that last no longer than 5 minutes. Narrative programs must structure their stories so that a segment can fit neatly within the commercial breaks. And even made-for-TV movies--the TV form that comes closest to films shown in theaters-are presented in narrative segments, mindful of exactly when the commercials are programmed. After all, to the television industry, programs are just filler, a necessary inconvenience interrupting the true function of television: broadcasting commercials.

The construction of these televisual segments and their relationship to each other are two major concerns of television's advertisers, producers, and programmers. For it is on this level that the battle for our continuing attention is won or lost. We should also be mindful of TV's segmental structure because it determines much of how stories are told, information presented, and commodities advertised on broadcast television.

SUMMARY

Televisual flow--Raymond Williams's term for television's sequence of diverse fragments of narrative, information, and advertising--defines the medium's fundamental structure. This flow facilitates the multiplicity of meanings, or polysemy, that television broadcasts.

Our consideration of televisual flow grows from three rudimentary axioms:

1. Television texts (programs, commercials, entire blocks of television time) contain meanings.

2. Not all meanings are presented equally. Textual devices emphasize some meanings over others and thus offer a hierarchy of meanings to the viewer. TV's polysemy is structured, by the dominant cultural order, into discourses (systems of belief).

3. The experience of television watching brings the discourses of the viewer into contact with the discourses of the text.

Televisual flow is riddled with interruptions. TV continually interrupts itself, shifting from one text to the next. And as often as the text interrupts itself, so too do we disrupt our consumption of television with trips out of the room or simple inattention. These constant interruptions lead television to adopt a segmented structure, constructing portions of TV in such a way as to encourage viewer concentration.

The aspiration of this guide is to analyze television's production of meaning.

We set aside the evaluation of television programs for the time being in order to focus on TV's structured polysemy and the systems that contribute to its creation: narrative and non-narrative structures, mise-en-scene, camera style, editing, and sound.

MORE READING:

The basic principle of television flow stems from Raymond Williams, Television: Technology and Cultural Form (New York: Schocken, 1974). This short book is one of the fundamental building blocks of contemporary television criticism.

John Corner, Critical Ideas in Television Studies (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999) devotes an entire section to the notion of flow. John Fiske, Television Culture (New York: Methuen, 1987) and John Ellis, Visible Fictions: Cinema: Television: Video (Boston: Routledge, 1992) both elaborate on the concept, too.

Fiske is also concerned with articulating television's meanings and how they may be organized into discourses. Todd Gitlin confronts television's role in advocating a society's dominant or "hegemonic" discourse in "Prime Time Ideology: The Hegemonic Process in Television Entertainment" in Television: The Critical View, ed. Horace Newcomb (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000): 574-594.

Further discussion of how meaning is produced in television texts may be found in the writings of British television scholars associated with the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies ( University of Birmingham, England). This school of analysis is summarized in Fiske's Television Culture and in his "British Cultural Studies and Television," in Channels of Discourse, Reassembled, ed.

Robert C. Allen (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1992). Students interested in the seminal work in this area should read Stuart Hall, "Encoding/Decoding," in Culture, Media, Language, eds. Stuart Hall, Dorothy Hobson, Andre Lowe, Paul Willis (London: Hutchinson, 1980). The implications of Dan Quayle's comments about Murphy Brown are examined in Rebecca L. Walkowitz, "Reproducing Reality: Murphy Brown and Illegitimate Politics," in Feminist Television Criticism, eds. Charlotte Brunsdon, Julie D'Acci, Lynn Spigel (New York: Clarendon, 1997). Walkowitz is concerned with the ideology of "family values" and the representation of women working in television news.

For thoughts on the erosion of broadcast television, see David Marc, "What Was Broadcasting?" in Television: The Critical View (2000): 629-648. He is one critic who believes the broadcast-TV era has already come to an end.

NOTES:

1. The bulk of TV Guide is comprised of more detailed descriptions of programs than is provided in the grid, but these are also arranged in terms of time slots rather than stressing first the individual programs. In contrast to this generalization, however, the magazine does emphasize eight or nine programs in its daily "Guidelines" feature, but these programs form a small segment of the television day.

2. Raymond Williams, Television: Technology and Cultural Form (New York: Schocken, 1974), 86.

3. Although The Simpsons and The Cosby Show spent two seasons opposed to one another in the same time slot, the latter was shifted to the later time period during the end of its run (Summer 1992).

4. John Fiske, Television Culture (New York: Methuen, 1987), 16.

5. Stuart Hall, "Encoding/Decoding," in Culture, Media, Language, eds. Stuart Hall, Dorothy Hobson, Andre Lowe, Paul Willis (London: Hutchinson, 1980), 134.

6. Fiske, 14.

7. Fiske, 105.