by John W. Linsley

Hi-fi enthusiast discusses results of his stereo equipment and installation experiments.

THERE WAS A PLEASANT aftermath to my article, A Purist Tackles Room Acoustics, which appeared in the April 1964 issue of Audio. It put me in touch with audio purists all over the country. The result was like an audio buff's dream come true because I had an opportunity to exchange ideas and to listen to a wide variety of fine hi-fi stereo systems.

Spurred on by so many questions tossed at me about my practical experiences, I continued to search for ways to improve my system. Here are some of the results of my experiments in trying to improve my hi-fi system, as well as observations, if not conclusions, based on them.

I was reasonably satisfied with my own system after hearing many others, though I did admit the need for several immediate improvements.

These included a better crossover for my Ionovac tweeters and a further improvement in a moving-pivot tone arm to reduce vertical and horizontal pivot friction. The arm's pivot now floats on distilled water, as shown in Fig. 1.

For some reason, such as the extreme variation in acoustics or just an inability to be completely unbiased, I found that my own horn loaded speaker system offered me a most enjoyable compromise between four full-range electrostatic speakers, on one hand, and two infinite baffle systems, on the other hand.

Now realize that I am just a dyed-in-the-wool purist who listens for subtle clues that might help me get just a little closer to the substantial feel and delicate clarity of live music.

Conclusions on transducers have to be subjective, naturally. After all, I also heard some irritating sounds in the big horn systems, but I still feel that the horn approach offers me, personally, the best chance of achieving realistic sound.

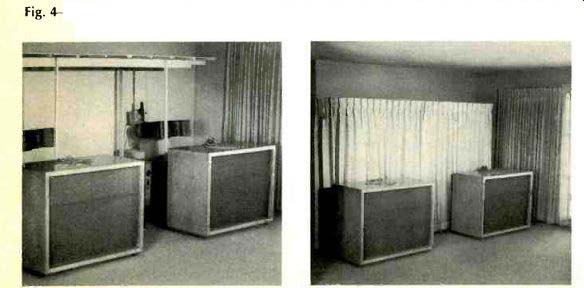

My original hope was that these horns could be projected out on to my back porch with only the mouth and a coaxial mid-range set up so that they project into the listening room. With this in mind, I designed and built two straight exponential horns with a 75 Hz cut-off frequency, a 60 sq. in. throat area, and a 30-in. x 38-in. rectangular mouth (which is almost the 3 foot square theoretical minimum recommended for use at 100 Hz) . Such a horn doubles in cross-sectional area every 13 inches along its axis and comes out to an overall horn and chamber length of 5 feet 8 inches. (As you might suspect, these mouth dimensions were influenced by the width of my front door.) The completed horn, made out of 1 inch thick chip board, weighs about 125 lbs. See Figs. 2 and 3.

I had intended to stop at this point, but I was tempted to test the importance of placing all speaker diaphragms on the same vertical plane to minimize phase cancellation at the crossover points.

As it turned out, it was fortunate that I hesitated to fill my back yard with gigantic 30 Hz horns because the vertical alignment principle proved to be most significant; I would not have been able to locate my mid-range diaphragms over a woofer that was 20 feet out in the back yard. In fact, I am now convinced that this vertical alignment principle is one reason that the 30 Hz horn did not become too popular even in the monophonic era, when only one horn of this size was needed.

Fig. 1--To minimize lateral and vertical pivot friction, the author's moving-pivot tone arm floats on distilled water.

Fig. 2--Dropping a plan to use a coaxial mid-range and tweeter arrangement so that the bulk of each 100to 500-Hz horn extends out from back-porch windows, the author placed all speaker diaphragms on the same vertical plane.

Fig. 3-The 100to 500-Hz horns are made of one-inch thick chip board. Horn and speaker chamber totals 5 ft. 8 in. long; the mouth is 30-in. high by 38-in. wide.

Since all my listening efforts left me content with the horn approach, I decided to find out what would happen if I eliminated the common practice of compromising horn length, straightness, and mouth area below 500 Hz.

As I had no reason for dissatisfaction with the sound of my 15 inch K horn under 100 Hz, I decided to limit my experiment to horns that would be theoretically adequate for use between 100 and 500 Hz, with electronic crossovers at 100 Hz. This arrangement yielded a most natural sounding bass when compared to the other systems so I decided to leave well enough alone until I had first explored the potential of larger horns in the 100 to 500 Hz range.

In a sense, the building of two straight experimental horns for use above 100 Hz was not too difficult, for a straight horn is rather simple compared to the complex construction required for a folded horn. The big problem was in finding enough space to house the horns.

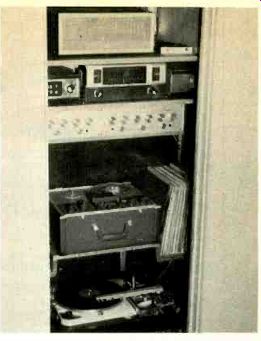

So I moved the horns back into the living room, and placed the midrange horns and tweeters in a vertical arrangement over the woofers. I noticed so much additional improvement that I simply could not give up the vertical diaphragm alignment, even though it makes my stereo setup almost eleven feet wide and six feet deep. See Fig. 4.

Now I fully realize that most people will think that I am just another far-out purist who has listened to so much music that he has started imagining differences that don't really exist. However, I assure you that there has been a good theoretical basis for everything I have heard in the past, only it took years to find the missing conditions that made the theories yield positive results.

For example, all theoretical logic indicates that front horn loading should yield a vast improvement in accuracy and power handling capability. Yet, from the beginning of my hi-fi experience I had heard a certain irritating quality, in the big theater horns that initially led me to try cone-type mid-range speakers and, finally, run my Stephens theatre drivers at a lower level than most people would consider proper.

I still liked the resultant sound better than any other I could hear, but I had to admit that the difference was not as great as theory indicated it should be.

At first I was tempted to blame my source material or the possibility that my compromised horns under 500 Hz were not providing a sufficiently solid foundation for such powerful mid-range horns. Of course, there was some truth in both of these, but my efforts to improve these factors weren't yielding much improvement until I attacked room acoustics.

The rough correction of my room acoustics (by shifting furniture, adding drapes, etc.) smoothed down those mid-range horns and seemed to improve the whole system's performance. I had achieved a most pleasant-sounding system, but it was obvious that I had done this by toning down a sound that still wasn't quite as smooth as it should have been.

My first reaction was to try yet another improvement in the foundation under those big theatre-type mid-range horns. The net result appeared worthwhile at first. However, after a month of listening to those new 100 to 500 cycle horns, I finally had to admit that something was still wrong.

The new horns certainly gave the music a solid richness, but every once in a while I would hear an unnatural peak on a powerful horn passage or an irritating edge on the percussion sounds of instruments such as a vibraphone. Since these all seemed to occur around 500 Hz I thought that my home-made crossover networks were at fault and planned their early replacement.

Fig. 4--Since it was impossible to conceal the big horns fully without making

the listening room seem about 1/3rd smaller, draperies were placed 2 1/2 ft.

back.

Fig. 5--The author's present system includes the following components: ADC

10E stereo cartridge in a special moving pivot tone arm; Thorens TD-124 manual

turntable; Ampex 1260 4-track tape recorder; Marantz mono preamplifiers; Knight

AM tuner; Fisher FM tuner; Marantz electronic crossovers at 100 Hz and 3500

Hz; JBL N-500 crossover networks at 500 Hz; Eico 28-watt dual basic amplifier

above 3500 Hz; Marantz 40-watt basic amplifiers between 100 Hz and 3500 Hz.

The latter drives JBL theatre woofers to 500 Hz and Stephens P-35 theatre drivers

above 500 Hz. A Marantz 40-watt basic amplifier drives an Electro-Voice 15-in. "K" horn:

Ionovac tweeters and JBL high frequency lenses round out the system.

However, as indicated before, I finally decided to test the idea of lining up speaker diaphragms vertically, wherein I discovered that most of those irritating sounds had vanished. In addition, I was also pleasantly surprised to find that the absence of phase cancellation also filled in considerable detail around the 500 Hz range.

I eventually replaced my homemade crossover networks with J.B.L. N-500 professional networks just to see if such high-quality networks might yield a small but worthwhile improvement. They did yield a small but apparent improvement in clarity both above and below 500 Hz.

(Audio magazine, Jan. 1968)

Also see:

Stereo Discs: 10 Years Old Stereo Disc Cutting, by Albert B. Grundy (Jan. 1968)

Audio Pro's at Show Time (Jan. 1968)

= = = =