by CHARLES R. DOTY, Sr.

IT WAS JUST ABOUT this time ten years ago when stereo discs became a commercial reality. Amidst intra industry wrangling about which system to adopt, a record company (Audio Fidelity) jumped the gun and produced a stereo record based on the Westrex 45° /45° system, as attendees of the New York high fidelity show at the end of '57 might recall. Shortly thereafter, the Westrex system was adopted by the Record Industry Association of America (RIAA), and the stereo disc and stereo disc playback equipment entered the main stream of America's home entertainment scene.

The single-groove stereo record spawned single-stylus phono cartridges with two internal elements.

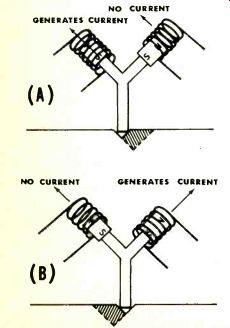

The playback system, as we know it today, is based on a stylus following the undulations of a record groove which is cut with groove walls at a 90° angle to each other, each 45° from the horizontal, as shown in Fig. 1. The motion that the stylus makes while in a stereo record groove is transformed into two distinct signals. Of course, it is impossible for a playback stylus to move in separate 45-deg. directions simultaneously. Actually, signals are generated according to the resultant of two vector forces, as illustrated in Fig. 2. So unlike mono records, which employ grooves that cause styli to move laterally, stereo records induce styli to move both laterally and vertically.

Fig. 1-Drawings show how movement

of a stylus in a stereo record groove can cause an output in a phono cartridge's

right channel (A) or left channel (B). NO CURRENT GENERATES CURRENT (A) NO

CURRENT GENERATES CURRENT

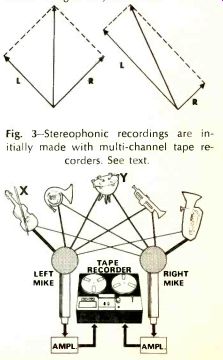

Some basic stereo system setup pointers are recapitulated here for new readers. Figure 3 shows the principle of stereo reproduction. In this mode of operation the sounds are picked up by a microphone on the left and a microphone on the right of the musicians. More than two microphones are often used to feature certain instruments, but the principle is the same. The violin on the left, marked X, is nearest to the left microphone. The left microphone will therefore pick up more sound energy from the violin than the right microphone. In the case of the drum, marked Y, equal sound intensity will be picked up by both the left and right microphones as it is located midway between them.

The sounds picked up by the left and right microphones are passed through separate amplifiers and recorded on magnetic tape. At a subsequent time the tape data is transferred to a master disc. By ingenious use of a combination of lateral and vertical motions, the master disc cutting stylus engraves both information channels in the side walls of a single V-shaped groove. Each groove wall is engraved at a 45 degree angle with respect to the disc surface.

When the finished records are played, the stereo cartridge stylus will respond by producing two independent outputs which are identical to the sounds heard by the left and right microphones during the recording session. These sounds are amplified (by separate amplifiers) and fed to left and right speaker systems, the combined output of which produces the stereo effect. Violin X will be heard on the left and drum Y will be heard midway between the two speakers. Other instruments will assume their relative positions due to the difference in sound intensities picked up by the left and right microphones during the recording session. The result will be a sound pattern emitted by speakers which is identical to the sound field picked up by the microphones.

The mere fact that a stereo record is being played on stereo equipment does not necessarily mean that one is getting the full impact of its potentialities. (Nor does it imply that it is high fidelity sound.) Certain rules must be followed to obtain the best reproduction, as follows:

Speakers are potentially one of the most important units in a high fidelity stereo sound system. They must be installed properly if best results are to be obtained.

Before trying speakers in various positions in the room to determine the location where they sound best, they should be phased so that their cones will move in and out in unison.

A good check on proper phase is to position the speakers a few feet apart, facing toward you, and play a passage from a mono organ record containing low pedal notes. Controls should be set to "MONO" or "A+B." Note the intensity of the low notes and then reverse the two connecting wires to one of the speakers and play the same passage a second time. The wiring arrangement which produces the loudest low note is the in-phase condition. Once established, these connections should remain the same for the tests to follow and thereafter. The wires should be marked to insure that they can be reconnected to the proper terminals of the amplifiers and speakers at any future time.

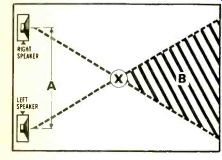

Fig. 4-Yardstick guide to setting up stereo speakers. (A) is distance between

speakers; (X) is same distance, between speakers; (B) is the area where stereo

effect is most pronounced.

Next, the sound output of the speakers should be balanced. This can be accomplished by standing several feet in front of the speakers, midway between them (location X, Fig. 4 is recommended) and, listening to a mono record, manipulate the balance control until the sound appears to come from a point directly in front of you.

Next, try the speakers in different locations. They should be spaced between six and ten feet apart, depending upon the size of, the room and the distance from the listening area.

Placing the speakers in the corners of a long narrow room may be found to stimulate room resonances, producing a booming sound. Placing them away from the corners of a long wall may result in an undesirable loss of bass. The location of the speakers which is judged to produce the most natural sound is the one to use, ' assuming that it does not create havoc with room decor.

After the speakers have been located, the tone controls may be touched up to compensate for less than-ideal room acoustics.

Fig. 2--A stereo cartridge's stylus cannot be in two places at the same moment, of course. The stylus makes one resultant motion. The drawing at left shows the sum of equal left and right signals as a vertical motion line; at right, a strong left signal added to a weak right signal produces a diagonal stylus motion.

Fig. 3--Stereophonic recordings are initially made with multi-channel tape recorders. See text.

(Audio magazine, Jan. 1968)

Also see:

Stereo Discs: 10 Years Old Stereo Disc Cutting, by Albert B. Grundy

= = = =