Theorists and research investigators in many different areas of human behavior-attitude

change, group dynamics, psychotherapy, hypnosis, and social perception-share

a common interest in understanding the pre-dispositional factors which underlie

responsiveness to one or another form of social influence. While these researchers

have approached the study of pre-dispositional factors from widely different

points of emphasis, many of their findings converge on a few basic variables

which have been designated as "persuasibility factors." Several

studies of personality factors in relation to individual differences in persuasibility

were reported by Hovland, Janis, and Kelley in 1953. Since that time further

studies have been conducted to provide a more systematic analysis of the personality

correlates of persuasibility and also of the course of its development from

childhood through adolescence. . . .

Irving L. Janis and Carl I. Hovland: From Irving L. Janis and Carl I. Hovland, "An Overview of Persuasibility Research," Persondity and Persuasibility (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959), 1-16. Reproduced with permission of the authors and the publisher.

DEFINITION OF PERSUASIBILITY

By "persuasibility factor" is meant any variable attribute within a population with consistent individual differences in responsiveness to one or more classes of influential communications. The meaning of the key terms in this definition will become somewhat clearer if we consider a brief schematic analysis of the communication process involved in successful persuasion.

Whenever an individual is influenced to change his beliefs, decisions, or general attitudes, certain identifiable external events occur which constitute the communication stimuli, and certain changes in the behavior of the person take place which constitute the communication effects. Communication stimuli include not only what is said, but also all of the intentional and unintentional cues which influence a member of the audience, including information as to who is saying it, why he is saying it, and how other people are reacting to it.

The observable communication effects could be said to subsume all perceptible changes in the recipient's verbal and nonverbal behavior, including not only changes in private opinions or judgments but also a variety of learning effects (e.g. increased knowledge about the communicator's position) and superficial conformist behavior (e.g. public expression of agreement with the conclusion de spite private rejection of it). However, our main interest centers upon those changes in observable behavior which are regarded as components of "genuine" changes in opinions or inverbalizable attitudes. This requires observational methods which enable us to discern, in addition to the individual's public responses, those indications of his private thoughts, feelings, and evaluations that are used to judge whether the recipient has "internalized" the communicator's message or is merely giving what he considers to be a socially acceptable response.

We use the term "attitude change" when there are clear-cut indications that the recipient has internalized a valuational message, as evidenced by the fact that the person's perceptions, affects, and overt actions, as well as his verbalized judgments, are discernibly changed. When there is evidence of a genuine change in a verbalized belief or value judgment, we use the term "opinion change," which usually constitutes one component of attitude change. Almost all experiments on the effects of persuasive communications . . . have been limited to investigating changes in opinion. The reason, of course, is that such changes can readily be assessed in a highly reliable way, whereas other components of verbalizable attitudes, although of considerable theoretical interest, are much more difficult to measure.

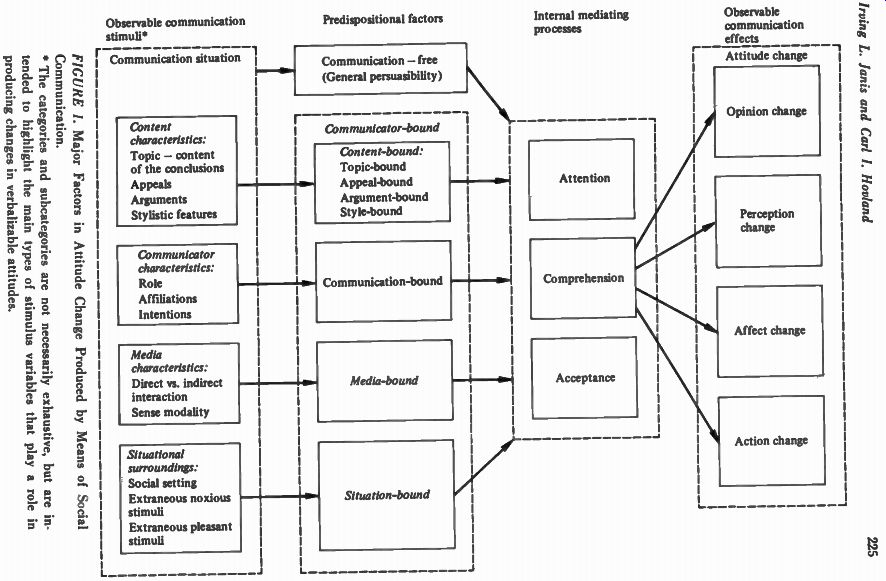

Neither "opinion change" nor "attitude change" is used to refer to those in stances of surface conformity in which the person pretends to adopt a point of view that he does not really believe. Thus, the area of opinion change with which we are concerned includes studies dealing with what has been referred to as "internalization" and "identification," but excludes those dealing with "compliance" (cf. Kelman, 1959) . Figure 1 gives a schematic outline of the major factors that enter into attitude change. The observable communication stimuli and the observable effects are represented as the two end-points of the communication process. These are the antecedent and consequent events that are observable; they constitute the empirical anchorage for two main types of constructs which are needed in order to account for the interrelationships between the communication stimuli and observable effects: pre-dispositional factors and internal mediating processes. Pre-dispositional factors are used to account for individual differences in observable effects when all communication stimuli are held constant. Constructs referring to internal, or mediating, processes are used in order to account for the differential effects of different stimuli on a given person or group of persons. In other words, internal-processes constructs have been formulated primarily to account for the different effects attributable to different types of communications acting on the same people; whereas, pre-dispositional constructs are needed to account for the different effects observed in different people who have been exposed to the same communications.

Hovland, Janis, and Kelley (1953) have reviewed and analyzed the experimental evidence on the effects of low vs. high credibility sources, strong vs. weak fear-arousing appeals, one-sided vs. two-sided presentation of arguments, and other such variations in communication stimuli. From such studies it has been possible to formulate a number of generalizations concerning the conditions under which the probability of opinion change will be increased or decreased for the average person or for the large majority of persons in any audience. Such propositions form the basis for inferences concerning the mediating processes responsible for the differential effectiveness of different communication stimuli.

Mediating processes can be classified in terms of three aspects of responsiveness to verbal messages (see Hovland, Lumsdaine, and Sheffield, 1949; and Hovland, Janis, and Kelley, 1953). The first set of mediating responses includes those which arouse the attention of the recipient to the verbal content of the communication. The second set involves comprehension or decoding of verbal stimuli, including concept formation and the perceptual processes that determine the meaning the message will have for the respondent. Attention and comprehension deter mine what the recipient will learn concerning the content of the communicator's message; other processes, involving changes in motivation, are assumed to deter mine whether or not he will accept or adopt what he learns. Thus, there is a third set of mediating responses, referred to as acceptance. Much less is known about this set of responses, and it has become the main focus for present-day research on opinion change. . . .

---------------

Figure 1

Two major classes of predispositions can be distinguished. One type, called "topic-bound," includes all of those factors which affect a person's readiness to accept or reject a given point of view on a particular topic. The other main type, called "topic-free," is relatively independent of the subject matter of the communication. In the discussion which follows, we shall first make some comments about the nature of topic-bound predispositions and about the more general class of "content-bound" factors, including those referred to as "appeal-bound," "argument-bound," and "style-bound." Then we shall attempt to extend the analysis of pre-dispositional factors by making further distinctions, calling attention to a number of content-free factors that are nevertheless bound to other properties of the communication stimuli. These various types of "communication-bound" factors will be contrasted with the unbound or "communication-free" factors to which our research efforts . . . have primarily been directed.

TOPIC-BOUND PREDISPOSITIONS

Topic-bound factors have been extensively studied by social psychologists and sociologists over the past twenty-five years, and many propositions have been investigated concerning the motives, value structures, group affiliations, and ideological commitments which predispose a person to accept a pro or con attitude on various issues. The well-known studies of authoritarian personalities by Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik, and others (1950) have provided a major impetus to ward understanding attitude change on specific issues, such as racial prejudice, in relation to unconscious motives and defense mechanisms. Some findings which bear directly on topic-bound predispositions have been reported by Bettelheim and Janowitz (1950) : Anti-Semitic propaganda (in the form of two fascist pamphlets) was most likely to be approved by men who either had already acquired an intolerant ideology toward Jews or who had acquired a tolerant ideology but were insecure personalities with much un-discharged hostility. Another pioneering study in this field is that of Smith, Bruner, and White (1956) ; these authors conducted a small series of intensive case studies for the purpose of determining the personality functions served by holding certain flexible and inflexible opinions about Soviet Russia and communism. Many other studies have been made concerning the personality correlates of readiness to accept favorable or unfavorable communications about specific types of ethnic, national, and political groups (Hartley, 1946; Sarnoff, 1951). Some recent studies of topic-bound predispositions deal with relatively general factors that are not limited to the modification of attitudes toward only one type of social group. For instance, Weiss and Fine (1955, 1956) investigated the personality factors which make for high readiness to accept a message advocating a punitive stand toward social deviants. The findings suggest that per. sons who have high aggression needs combined with strong extra-punitive tendencies will be prone to adopt a strict, punitive attitude toward anyone who violates social norms. In order to test this hypothesis in its most general form, it would be necessary to use many different communications to determine whether the specified personality attributes are correlated with attitude change whenever a punitive stand is advocated toward any type of social deviant. If the hypothesis is confirmed, we shall be able to speak of a very general type of topic-bound predisposition.

This example highlights the fact that the difference between topic-bound and topic-free is not necessarily the same as the dimension of specificity-generality.

Some topic-bound predispositions may be very narrowly confined to those communications expressing a favorable or unfavorable judgment toward a specific trait of a particular person (e.g. the members of an organization, after having been embarrassed by the gauche manners of their highly respected leader, would be disposed to reject only those favorable statements about him which pertain to a limited aspect of his social behavior). Other topic-bound predispositions may be extremely general (e.g. certain types of persons may be inclined to accept any comments which express optimism about the future). A topic-bound predisposition, however, is always limited to one class of communications (a narrow or a broad class) which is defined by one or another characteristic of the content of the conclusion.

Similar restrictions hold for some of the topic-free factors. For example, Hovland, Janis, and Kelley (1953) point out that many topic-free factors may prove to be bound to specific characteristics of the communication: Some of the hypotheses concerning topic-free predispositions deal with factors which predict a person's responsiveness only to those persuasive communications that employ certain types of argumentation. Investigations of topic-free predispositions ultimately may reveal some that are associated primarily with the nature of the communicator, others that are associated with the social setting in which the communication takes place, and perhaps still others that are so broad in scope that they are relatively independent of any specific variables in the communication situation.

Thus, for any communication, we assume that there are likely to be several different types of personality predispositions, topic-bound and topic-free, whose joint effects determine individual differences in responsiveness. The essential point is that, by also taking account of topic-free factors, it should be possible to improve predictions concerning the degree to which members of the audience will be influenced by persuasive communications. Such factors have generally been neglected in analyses of audience predispositions.

In the discussion which follows, we shall attempt to trace the implications of the distinction-which we now believe to be extremely important-between topic-free factors that are bound in some non-topic way and those that are completely unbound. A suggested list of bound predispositions is provided in the second column of Figure 1. We shall briefly consider those topic-free factors which are bound to other features of the communication situation before turning to a detailed examination of the unbound, or communication-free, factors.

CONTENT-BOUND FACTORS

The content of a communication includes appeals, arguments, and various stylistic features, as well as the main theme or conclusion which defines its topic.

The effectiveness of each of these content characteristics is partly dependent upon certain pre-dispositional factors which we designate as "content-bound."

APPEAL-BOUND FACTORS. In the content of many communications one finds appeals which explicitly promise social approval or threaten social disapproval from a given reference group (see Newcomb, 1943). Responsiveness to these social incentives partly depends upon the degree to which the person is motivated to be affiliated with the reference group (see Kelley and Volkart, 1952). Personality differences may also give rise to differences in responsiveness to special appeals concerning group consensus and related social incentives (Samelson, 1957). Different types of personalities may be expected to have different thresh olds for the arousal of guilt, shame, fear, and other emotions which can be aroused by special appeals. For example, Janis and Feshbach (1954) have found that certain personality factors are related to individual differences in responsiveness to fear-arousing appeals. Experimental studies by Katz, McClintock, and Sarnoff (1956, 1957) indicate that the relative effectiveness of rational appeals, and of self-insight procedures designed to counteract social prejudices, depends partly upon whether the recipient rates low, medium, or high on various measures of ego defensiveness.

ARGUMENT-BOUND FACTORS. Many variables have been investigated which involve stimulus differences in the arrangement of arguments and in the logical relationship between arguments and conclusions. Cohen, in Volume 1 of the present series (1957, Ch. 6), presents evidence indicating that pre-dispositional factors play a role in determining the extent to which an individual will be affected by the order in which information is presented. Individuals with low cognitive need scores were differentially influenced by variations in order of presentation while those with high scores were not. One would also expect that individual differences would affect the degree to which a person will be influenced by such variations as the following: (1) The use of strictly rational or logical types of argument vs. propagandistic devices of overgeneralization, innuendo, non sequitur, and irrelevant ad hominem comments. (2) Explicitly stating the conclusion that follows from a set of arguments vs. leaving the conclusion implicit. (A comparison of effects for subjects with high and low intelligence is presented in Hovland and Mandell, 1952.)

STYLE-BOUND FACTORS. Differences in social class and educational back ground probably account for some of the individual differences in responsiveness to variations in style-for example, a literary style as against a "folksy" approach. Other variations in treatment that may be differentially effective are technical jargon vs. simple language; slang vs. "pure" prose; long, complex sentences vs. short, declarative sentences. Flesch (1946) and other communication researchers have presented evidence concerning individual differences in responsiveness to such stylistic features.

COMMUNICATOR-BOUND FACTORS

The effectiveness of a communication depends on the recipient's evaluation of the speaker (see, e.g., Hovland and Weiss, 1951-52). The phase of the problem which has been most extensively studied is that concerned with the authoritativeness of the communicator. That personality differences in the recipients are associated with the extent to which particular communicators are effective is clearly shown in a study by Berkowitz and Lundy (1957). Their college-student subjects who were more influenced by authority figures tended to have both higher self-confidence and stronger authoritarian tendencies (high F-scale scores) than those who were more influenced by peers.

The affiliation of the communicator is also an important factor, in interaction, of course, with the group membership of the recipient. Thus the communicator who is perceived as belonging to a group with which the recipient is also affiliated will be more effective on the average than a communicator who is perceived either as an outsider or as a member of a rival group (Kelley and Volkart, 1952; Kelley and Thibault, 1954). When, for example, a speaker's affiliation with a political, social, religious, or trade organization becomes salient to the audience, persons who are members of the same organization will be most likely to be influenced by the speaker's communication.

Finally, the intent of the communicator is perceived differently by different members of the audience, with a consequent influence on the speaker's effectiveness. A number of studies have shown that the fairness and impartiality of the communicator is viewed quite differently by individuals with varying stands on an ideological issue, and this in turn is related to the amount of opinion change effected. For a discussion of this problem see Hovland, Harvey, and Sherif (1957).

MEDIA-BOUND FACTORS

It seems probable that some persons will be more responsive to communications in situations of direct social interaction, whereas others may be more readily influenced by newspapers, magazines, radio programs, television, movies, and mass media in general. (See the discussion by Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet, 1944, concerning the psychological differences between propaganda emanating from mass media and from informal social contacts.) Other media characteristics that may evoke differential sensitivities involve variations in the sense modalities employed: e.g. some people may be more responsive to visual than to auditory media. There is some evidence that individuals with less education may be more influenced by aural presentations (e.g. by radio and lectures) than by printed media (see summary of studies by Klapper, 1949). However, few systematic studies have been made as yet on the relation between predispositions and media characteristics.

SITUATION-BOUND FACTORS

While no systematic studies can be cited, there are indications that some persons tend to be more influenced when socially facilitative cues accompany the presentation of a persuasive communication (e.g. presence of others, applause). The experiments by Asch (1952) and other investigators contain some indirect implications bearing on individual differences in responsiveness to an expression of consensus on the part of others in the audience. Research by Razran (1940) and an unpublished study by Janis, Kaye, and Kirschener indicate that some people are affected by the pleasantness or unpleasantness of the situation in which a communication is received. For example, the effectiveness of persuasive messages was found to be enhanced if they were expressed at a time when the subjects were eating a snack. We might expect to find some personality factors associated with low vs. high sensitivity to extraneous stimulation of this type.

Just as in the case of topic-bound factors, each of the above content-bound, communicator-bound, media-bound, and situation-bound factors may include some predispositions that are very narrow in scope (e.g. applicable only to communications which emanate from one particular communicator) and other pre dispositions that are broadly applicable to a large class of communications (e.g. to all communications emanating from purported authorities or experts). It is the predispositions at the latter end of the specificity-generality continuum that are of major scientific interest, since they are the ones that increase our theoretical understanding of communication processes and help to improve predictions of the degree to which different persons will be responsive to social influence.

PREDICTIVE VALUE OF UNBOUND PERSUASIBILITY FACTORS

Unbound persuasibility factors . . . involve a person's general susceptibility to many different types of persuasion and social influence. We assume that these factors operate whenever a person is exposed to a persuasive communication and that they do not depend upon the presence or absence of any given type of content or on any other specifiable feature of the communication situation. Thus un bound factors are communication-free, and this differentiates them from even the most general of the bound factors.

One long-range product of research on bound and unbound persuasibility factors might be conceived of as a set of general formulae which could be used to predict, within a very narrow range of error, the degree to which any given per son will be influenced by any given communication. The formulae would be multiple regression equations and would specify the personal attributes (X1 ,X2, X3, . . . Xn) that need to be assessed in order to make an accurate prediction concerning responsiveness to a given class of communications ( Y A). More than one regression equation would presumably be necessary in order to take account of the major bound personality factors; i.e. certain attributes might have high weight for one type of communication ( Y A) but low or zero weight for other types ( YD, Y c, Y D, etc.). This way of looking at persuasibility research helps to clarify the essential difference between bound and unbound factors. Un bound factors would enter with a sizable weight into every one of the regression equations, irrespective of the type of communication for which predictions are being made ( YA, Yft, Yz). Bound factors, on the other hand, would have varying weights, ranging from zero in some regression equations to very high weights in others.

The concept of a set of multiple regression equations highlights the descriptive character of persuasibility factors. They are, in effect, individual traits whose consequences are directly measurable by observing changes in verbal behavior and in overt nonverbal behavior. They enable us to estimate the probability that a given individual will change his opinions or attitudes in response to a given class of communications. The unbound predispositions are communication-free factors which permit estimates concerning the probability of change in response to any communication, i.e. they purport to apply universally to all communications.

It should be noted, incidentally, that a given attribute (e.g. degree of motivation to conform to the demands of others) might turn out to be partly bound as well as unbound. That is to say, the attribute may be a communication-free factor because it enters into every regression formula with a substantial weight but, at the same time, it might be partly bound in that the weight may be much higher in a regression equation that applies to one particular class of communications (e.g. those which contain arguments and incentives appealing directly to the recipient's social conformity motives). It should also be borne in mind that a seemingly unbound factor might actually be bound in a rather subtle or unexpected way. During the early stages of research, a given persuasibility factor may seem to be unbound, since it consistently enables better-than-chance predictions for a wide variety of communications differing in topic, communicator characteristics, media characteristics, and so forth. Subsequent research, however, might reveal that the factor is bound to some very broad category (e.g. it may apply to one-way mass-media situations but not to direct interpersonal relationships in which two-way communication takes place). Although more limited in its scope than had at first been apparent, the factor might, nevertheless, remain a valuable predictive attribute for an extremely wide range of communication situations. This example again points to the need for regarding "bound" and "unbound" as end-points of a continuum rather than as a dichotomy, since there may be wide variation in "degree of boundedness." Some bound factors may apply to such small or trivial classes of communications that they are of little value for predictive or theoretical purposes, whereas other bound factors may pertain to extensive and socially significant classes of communication. Certain bound factors may conceivably turn out to be almost as broad in scope as the unbound ones and may permit the formulation of some general laws of persuasibility with relatively few limiting conditions. Thus, the quest to discover unbound persuasibility factors need not be regarded as having failed in its scientific purposes when the investigator discovers instead a set of bound factors. If they are sufficiently broad in scope, they may help to formulate general propositions concerning the type of person who will be influenced by various kinds of social communications.

In line with this conception, we regard the purpose of the persuasibility re search represented . . . to be that of discovering and assessing both unbound factors and bound factors of broad scope. . . .

REFERENCES

ADORNO, T. W., F RENKEL, BRUNSWICK, ELSE, LEVINSON, D. J. and SANFORD, R. N., 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York, Harper.

ASCH, S . E, 1952. Social Psychology. New York, Prentice-Hall.

BERKOWITZ, L. and SANDY, R. M., 1957. Personality characteristics related to susceptibility to influence by peers or authority figures. 1. Pers., 25, 306-16.

BETTELHEim, B. and JANOWITZ, M., 1950. Dynamics of Prejudice. New York, Harper.

COHEN, A. R., 1957. Need for cognition and order of communication as determinants of opinion change. The Order of Presentation in Persuasion, ed., C. I. Hovland. New Haven, Yale University Press.

FLEscH, R., 1946. The Art of Plain Talk. New York, Harper.

HARTLEY, E. L ., 1946. Problems in Prejudice. New York, King's Crown Press.

HOVLAND, C. L, HARVEY, O. J., and SHERIF, M., 1957. Assimilation and contrast effects in reactions to communication and attitude change. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 55, 249-52.

HOVLAND, C. L. JANIS, I . L ., and KELLEY, H. H., 1953. Communication and persuasion. New Haven, Yale University Press.

HOVLAND, C. I ., LUMSDAINE, A. A., and SHEFFIELD, F. D., 1949. Experiments on Mass Communication. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

HOVLAND, C. I. and MANDELL, w., 1952. An experimental comparison of conclusion-drawing by the communicator and by the audience. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 47, 581-8.

HOVLAND, C. I. and WEISS, W., 1951-52. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Publ. Opin. Quart., 15, 635-50.

JANIS, I . L . and FESHBACH, s., 1954. Personality differences associated with responsiveness to fear-arousing communications. J. Pers., 23, 154-66.

KATZ, D., SARNOFF, I ., and MCCLINTOCK, C., 1956. Ego-defense and attitude change. Human Relat., 9, 27-45.

KATZ, D., MCCLINTOCK, C., and SARNOFF, I ., 1957. The measurement of ego defense as related to attitude change. J. Pers., 25, 465-74.

KELLEY, H. H. and THIBAULT, J. W., 1954. Experimental studies of group problem solving and process. In Handbook of Social Psychology, Vol. 2, cd. G. Lindzey. Cambridge, Mass., Addison-Wesley, 735-85.

KELLEY, H. H. and VOLK ART, E. H., 1952. The resistance to change of group-anchored attitudes. Amer. Socio!. Rev., 17, 453-65.

KELMAN, H. C., 1959. Social Influence and Personal Belief: A Theoretical and Experimental Approach to the Study of Behavior Change. Unpublished manuscript.

KLAPPER, J. T., 1949. The Effects of Mass Media. New York Bur. Appl. Soc. Research, Columbia University (mimeo.).

LAZARSFELD, P . F., BERELS014, B., and GAUDET, HAZEL, 1944. The People's Choice. New York, Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

NEWCOMB, T. M., 1943. Personality and Social Change. New York, Dryden.

RAZRAN, G. H. S., 1940. Conditioned response changes in rating and appraising sociopolitical slogans. Psychol. Bull., 37, 481 (abstract).

SAMELSON, F., 1957. Conforming behavior under two conditions of conflict in the cognitive field. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 55, 181-7.

SARNOFF, I., 1951. Identification with the aggressor: some personality correlates of anti Semitism among Jews. J. Pers., 20, 199-218.

SMITH, M. B., BRUNER, J. S., and WHITE, R. W., 1956. Opinions and Personality. New York, Wiley.

Weiss, W. and FINE, B. J., 1955. Opinion change as a function of some intrapersonal attributes of the communicatees. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol, 51, 246-53.

Weiss, W. and FINE, B. J., 1956. The effect of induced aggressiveness on opinion change. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 52, 109-14.

Also in Part 4:

- Communication Theory: Interaction

- The Concepts of Balance, Congruity, and Dissonance

- A Summary of Experimental Research in Ethos

- An Overview of Persuasibility Research

- The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitudes

- The Social Judgment-Involvement Approach to Attitude and Attitude Change

- Processes of Opinion Change

- The Communication