In May, 1947, a magazine called Radio was superseded by another with editorial

content devoted to "the sadly neglected audio engineering field." This

new publication, appropriately called Audio Engineering, was created to cover "developments

in sound engineering as it relates to commercial broadcasting, transmitter

and receiver manufacturing, sound-on-film equipment, recording (disc, wire,

and tape), public address, industrial sound, and acoustics," Editor John

H. Potts commented in his introductory column.

Recording itself, which Potts found drew little journalistic attention, would also be covered.

Moreover, he chose to include record reviews, "unique in a technical magazine." After introducing his record critic, one Edward Tatnall Canby (who also covered recordings for the Saturday Re view of Literature, albeit from a less technical viewpoint than he would adopt in this new journal), John Potts moved on to the subject destined to become the publication's focus. "No discussion of audio engineering gets very far before the matter of fidelity is brought up," he commented.

The State of Audio When Audio Was Born

When the May, 1947 issue of Audio Engineering appeared, the seeds of home hi-fi had already been planted across America.

In a small New York City factory, Avery Fisher was turning out expensive, high-performance radio phonographs. The previous year, these had caught the attention of Fortune magazine, which surveyed the state-of the-art and singled out the Fishers as "best...in price and performance." In the little Texarkana town of Hope, Arkansas, not far from the spot where Jim Bowie is said to have forged the first of his eponymous knives, speaker pioneer Paul Klipsch was beginning to carve out his own future in high fidelity with an innovative corner horn speaker.

On the West Coast, a former signal corps major named John T. Mullin was demonstrating the magnetophon, two of which he had dismantled and shipped home from Germany at the war's end. Harold Lindsay of Ampex, who was to become project engineer for the firm's magnetophon--based tape recorder, had already heard the remarkable German machine. Singer Bing Crosby, whose radio show Mullin would soon be taping for delayed broadcast, was about to audition it as well.

NEW MAC Management

In March, 1949, John Potts died, and the editorial helm at Audio Engineering was assumed by Managing Editor C.G. "Mac" McProud. McProud proceeded to produce more and more content geared to the "audio buff," the dedicated hobbyist who, he later recalled, "might be a surgeon, dentist, lawyer or college student during the major part of his day." By that time, the AES was up and running. "The first 'feeling out' of readership on an Audio Engineering Society was in the form of a 'planted' letter" in Audio Engineering early in 1948, McProud noted in a retrospective article penned for the magazine's 20th anniversary issue. Moreover, "Audio Engineering was represented on the steering committee that did all the early work, and later on the board of governors." McProud himself became Vice President of the AES in 1951 and President the following year.

For some time, Audio Engineering also carried a regular section that served as the first Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. As the AES grew larger and more self-sufficient, its Journal became a stand-alone publication, one which McProud felt was better-suited for highly technical articles than its mother magazine. Audio Engineering, he felt, could now serve "to furnish good reading, accurate technical information, and general help to the dedicated audio buff." On the March, 1954 cover, McProud's pride carried a new logo with the word Audio dominant.

Under it, in much smaller type, were three terms Engineering, Music and Sound Reproduction-that together defined the new editorial direction.

There's No Business Like Show Business

In the late 1940s, no one could have predicted that high fidelity would become a household term. However, as the seminal 1946 Fortune article indicated, America's ears were open to developments in audio.

Audio Engineering's staffers were determined to take advantage of the fact. To do so, they ventured beyond print and conceived the first-ever public hi-fi exposition. In 1949, Harry N. Reizes, the magazine's Advertising Manager, presided over the first of a series of Audio Fairs at Manhattan's Hotel New Yorker. The event's official sponsor was the AES, and the show was held in con junction with the group's first convention.

For hi-fi manufacturers like Avery Fisher, who always valued customer contact, such exhibitions were more than product showcases-they were market research. "We learned a great deal from them," the man whose name now appears on one of New York City's two major concert halls later recalled. "We didn't have to send out a bunch of college boys with questionnaires to find out what we should be making. I was able to speak to the actual consumers, or potential consumers, to find out what they liked about our present products and what they would like to see in our future products." For Audio Fair attendees, these events afforded personal contact with equipment designers and manufacturers. They were rare opportunities to meet and speak with the men whose names graced the name plates of components owned or coveted.

"For them to be able to come into our rooms and talk to the man whose name was on the product meant a great deal to them," Fisher commented in a 1990 Audio interview. "They felt they were talking to headquarters, and they were." In May, 1952, an Audio Fair opened in Chicago, and in February, 1953, a similar event was held in Los Angeles. By 1954, the concept had reached Japan. From November 27 to December 5 of that year, the Nippon Audio Association sponsored an event that featured 49 manufacturers, all of whom manned booths at Matsuya, one of Tokyo's largest department stores.

The '54 Tokyo Audio Fair included a three-channel stereo broadcast for which radio stations JOKR, JOFR and JOQR joined forces. The stereocast was made on standard broadcast frequencies, and it was conveyed to Japanese show-goers by means of three receivers and loudspeakers spaced around a listening room.

An Audio correspondent reported on the Japan Fair in the February, 1955 issue.

Given 20/20 hindsight, some present-day readers would find hints in his story (an attendance figure topping 55,000 was one) to suggest the influence that nation would later assert on hi-fi.

===============

HI-FI Bug BITES IN JAPAN

In his February, 1955 report from Japan, Warren Birkenhead noted that LP discs had begun "to emerge in quantity from the pressing plants of certain Japanese record companies" just a year earlier. He went on to state that more than 50,000 "hi-fi sets" were assumed to be in use there. Though their cost was estimated at $90 each on average, the fact that "more than 95 per cent of the Japanese hi-fi enthusiasts build their own amplifiers and assemble their own hi-fi systems" coupled with the much lower price of parts in that nation put the average system value at "several times that figure." "In the Kanda area of Tokyo," Birkenhead marveled, "one can browse through more than a hundred retail stores that sell hi-fi parts.

Loudspeakers, amplifiers, amplifier parts, pickup cartridges, turntables, preamplifiers and equalizers are all in abundant supply ...and are hawked... throughout the day and night." "One enterprising Kanda hi-fi [merchant] has set up a coffee shop on the second floor above his establishment. There, prospective hi-fi customers, while drinking coffee, may listen to LPs reproduced through the various [components] on sale in the store below." "There is always a demand in Japan for parts and equipment made in the United States," the writer observed. "If a store manager can display a Stateside item, he can always be sure of a higher price and a quick turnover. For this reason, there is a tremendous temptation to market Japanese-made articles with a Stateside label. This practice is definitely deplored by the Japanese government and stopped when detected." That deception, Birkenhead added, was bound "to remain a factor until the Japanese-manufactured components of Japanese de sign are more widely accepted by the Japanese themselves." The last observation merits a foot note. While the role Japan's own engineers and corporations have since played in hi-fi history is formidable, American equipment's most avid fans continue to include Japanese aficionados.

In recent years, our nation's industrial community has faced mounting criticism, much of which has been directed at mediocre product quality.

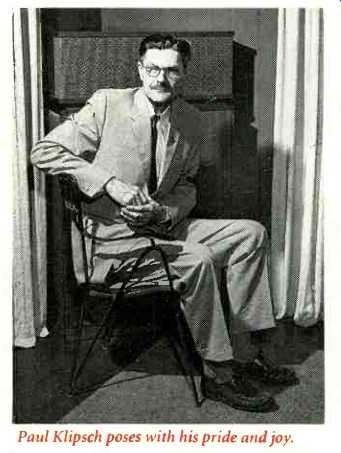

Yet American high fidelity equipment has never reflected mediocrity, largely because love, as much as or more than money, has been its principal impetus. As Paul Klipsch, one of hi-fi's founding fathers, put it just a few years ago, "audio was a hobby and then a profession, but I still consider myself an amateur in that an amateur is one who practices his art for love."

==============

MAN WITH A HORN

Even in the company of his fellow hi-fi pioneers, strong-minded individualists driven by a passion for music and good sound, Paul Klipsch stands out. A cross between Ben Franklin and Daniel Boone, the six-foot-three-inch speaker maker has, for the last half century, holed up in the southwest-Arkansas town of Hope. He was sent there by the army during World War II and, in 1946, purchased a 3,000 square-foot building from the government to manufacture a horn loudspeaker of his own design.

Musical instrument makers have long known that horns, for the sake of compactness, can be curled. Klipsch folded the horn in his speaker into segments connected by acute angles. He also split the horn into two lengthwise sections that rejoin at the mouth. And, by specifying that it be placed in the corner of a room, he effectively ex tended his horn. All this makes the Klipschorn extremely efficient.

------- Paul Klipsch poses with his pride and joy.

Today, in an industry where an annual crop of new products springs up as inexorably as crabgrass, the venerable Klipschorn lives on, an audio evergreen. Not unlike its creator. Though Klipsch sold his company to a cousin three years ago, he still appears there nearly every morning-in spite of the fact that he turned 88 in March.

Paul Wilbur Klipsch favors martial music, oxymorons, trains and vintage planes.

For much of his life, he has tracked gold mining stocks and other economic data, making notations in ledgers kept for that purpose. An instrument-rated pilot (who gave up flying only at age 77), Klipsch is known for travelling with three watches, one set to the time at his destination, one to the time at home and the third to Greenwich mean time. Friends and associates recall his crack marksmanship with small bore weapons, and many in the industry remember his typical reaction to extravagant hi-fi claims. He would expose a small button pinned underneath a lapel.

On it was printed a single word: Bullshit.

Many who live there think of Hope, Arkansas as the source of the world's largest watermelons. In the 1930s, legend has it, a local farmer grew one that weighed just under 200 pounds. He called it the Hope Triumph. But that was before Paul Klipsch came to town. Clearly this audio industry original, who named a speaker Heresy then sold it to churches, has since earned the right to that title.

---- In 1951, Audio columnist Bert Whyte was a Concord Radio sales

executive.

Testing

Then and Now Even Audio's first Equipment Reports (the ancestors of today's comprehensive product reviews), published during the early 1950s, were illustrated by graphs containing performance data. Producing such graphs was a lot harder in those days than it is now.

Users of early test gear, made avail able by Heath and, somewhat later, Boonton, had to make measurements at various frequencies by doing individual calculations at each. Then, every graph had to be plotted point by point and drawn manually. Today, an audio tester can generate 15 or 20 graphs and laser-print them in the time it once took to produce just two or three.

More importantly, today's measurements can be as much as 100 times more accurate. There is a downside, of course. While a 1950s lab might have cost a few thousand dollars, today's state-of-the-art facility requires an in vestment closer to the six figure mark.

One crucial piece of equipment not always considered in the early days of hi-fi testing was the ear. However, as Gene Pitts, this magazine's Editor since 1973, points out in his Epilogue, Audio has always advised that listening and measuring go hand in hand.

WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO THE FINIAL TURNTABLE?

It was designed to play LPs with a laser beam so as not to harm them. Its production price, we were told, would be relatively high but acceptable to serious hobbyists.

The months came and went, but the incredible light-bearing Finial turntable never went into production.

The time was the late 1980s, and the LPs that Finial's rainbow was to play were becoming an endangered species. This very fact probably saved the machine, which is now in limited production in Japan. Not as a hobbyist diversion but as an archival tool.

Its cost is that of a mid-priced Japanese sports car. High but acceptable to serious archivists.

Some Daring Young Men & Their Hi-Fi Machines

--------- Thomas Alva Edison: Giving shape to the 20th century

--------- Peter Goldmark shows off the new 33'% RPM LP record.

--------While still a college student Ray Dolby (3rd from left) helped develop the video tape recorder.

---------C Robert Fine and Wilma Cozart Fine were the forces behind Mercury's now- legendary Living Presence series of recordings.

-------Henry Kloss: Fusing others ideas into innovative hi-fi products

In the late '40s and beyond, Paul Klipsch and his fellow audio entrepreneurs worked diligently to distill better sound from their components, widening frequency response and lowering noise and distortion an increment at a time. Though many feared it would happen, hi-fi fever never broke out among the large manufacturers of the era. (If it had, they could have pummeled the smaller firms into the ground.) One notable exception was a development that occurred at General Electric: the invention of a phono cartridge that reduced tracking force, previously in the range, to just five grams.

The variable reluctance cartridge was conceived by William Bach man, who worked at GE during World War II. At that time, company engineers spent their days on projects with military goals while nights were devoted to endeavors the company hoped would result in saleable postwar products.

Bachman's name is associated with another late-1940s innovation crucial to the growth of high fidelity. From GE, he moved to the slot of Chief Engineer at Columbia 30 gram Records Research Laboratories and worked with Peter Goldmark of CBS Laboratories (a sister research facility) to develop the LP.

The 33 1/3 RPM vinyl record soon became the fountainhead of high fidelity sound and continued to spew music for some four decades before being capped by the Compact Disc.

Bachman's patent on the variable reluctance cartridge was later invalidated due to the existence of prior art, but this detracts neither from his creativity nor his importance to hi-fi. Edgar Villchur's patent on the acoustic suspension speaker was also invalidated after the Acoustic Research co-founder lost a suit against rival Electro-Voice in the late 1950s. (In this instance, a court cited disclosures by Harry F. Olson, who was granted over 100 patents in his life time.) Yet it was Villchur's company that actually produced a high fidelity speaker small enough to make stereo viable in the home.

In discussing Villchur's suit, his former partner, Henry Kloss, has underscored the importance of those who hammer the ideas and inventions of others into work able product formats. Kloss's own remarkably prolific career in audio illustrates this point dramatically.

Villchur first described his acoustic suspension speaker to Kloss when the latter, then serving in the Army Signal Corps at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, was en rolled in a New York University night course in high fidelity that Villchur taught. Kloss already had a small speaker cabinet manufacturing facility in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He also had two friends, Malcolm Low and J. Anton Hofmann, who kicked in $2,500 each and joined him and Villchur as founding partners in Acoustic Re- While Villchur labored at his home in Woodstock, New York, Kloss worked at the company's Cambridge facility, first on low-frequency driver designs for the AR-1 and, after that, the smaller AR-2. After parting ways with Villchur and going on to found KLH Research and Development with Low and Hofmann, Kloss designed the legendary KLH Six. Later, at his third company, he produced the Advent loudspeaker, another best seller.

It was Hofmann, a physicist (and son of acclaimed piano virtuoso, Josef Hofmann), who codified the key variables of acoustic suspension design-bass response, box size and efficiency-deriving formulae that governed the low frequency response of sealed-box speakers. Kloss delineated what he called "Hofmann's Iron Law" in the March, 1971 issue of Audio, stating that he could, and would, "make perfectly rigorous statements of proportionality which will permit us to precisely predict the performance of any new speaker as a function of the change in parameters of a prototype speaker."

Kloss later built products that stemmed from ideas other than those of Villchur (or Olson). In 1960, KLH introduced his Model Eleven, a portable stereo record player with detachable speakers that folded together to form its own carrying case.

This was one of the first successful audio industry products to employ transistors.

In 1967, Kloss heard about Ray Dolby's noise reduction system, initially intended H for professional applications. It was Kloss who pushed for a consumer version of Dolby, which he originally saw as a boon to home open-reel users. Somewhat later, he linked the system with a previously unsuccessful DuPont product, chromium-dioxide tape. Thanks to the magi cal midwifery at which Henry Kloss excels, these inventions helped make the Philips cassette, introduced for dictation purpose's, a music storage medium that went on to surpass the LP in sales.

FAST FORWARD

Sidney Harman is the hi-fi industry's Re naissance man. He founded Harman-Kardon 40 years ago and today serves as Chair man and CEO of Harman International Industries, parent of JBL, Infinity, Harman Kardon and several other companies. (At press time, Wall Street analysts who follow the stock estimated Harman International sales for fiscal 1992 would total approximately $600 million.) He has an earned doctorate from The Union Institute, was for three years President of Friends World College, a worldwide experimental Quaker college, and served as Deputy Secretary of Commerce of the United States in 1977 and 1978.

Below, Dr. Harman comments on the future of the industry he helped mold.

I grew up in an era when the forecasts of David Sarnoff, the fabled Chairman of RCA, were awaited with the excitement now reserved for Academy Award night.

Those predictions were invariably of products and services which he alone could visualize. And numbers of them were ultimately realized. I leave that kind of pre diction to others. It is the way in which we proceed into the future that I would emphasize.

------- Sidney Harman

This is a new world-a different world.

The emphasis cannot be on product visions but on consumer needs and it cannot be mere rhetoric. This industry can surge if we behave as marketing anthropologists respectful of the differences in markets and cultures and mindful that our job is to respond to real consumer needs.

The view that a confluence of computers and home entertainment is inevitable may be correct, but we had better make sure that it is a vision which resonates with real consumer needs rather than being only an expression of what we are able to do technically.

The old Barnum saw that "there is a sucker born every minute" was a reference to the consumer. If we don't have our wits about us, the sucker may prove to be us.

WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO ELCASET?

Or for that matter, the 8-track cartridge and open reel? The lowly Philips cassette, introduced as a dictation medium, was improved enough to replace both those formats in the home and car. It also made the Elcaset (a mid-70s development that, for improved fidelity, employed a speed of 3.5 ips and, like a video cassette, pulled the tape from its shell during play) redundant even as it was being introduced.

Now, precisely 50 years after the first trial production run of magnetic recording tape spun off the machines at BASF, many wonder whether Philips' newest development, the digital compact cassette (DCC), will become the next home recording medium of choice. Or if a recordable optical medium (such as Sony's new mini disc) will relegate tape to museums.

Stay tuned.

WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO SQ, QS AND CD-4?

In the early 1970s, many industry forecasters predicted the demise of two-channel stereo. One problem was that a trio of four-channel systems vied for attention. RCA touted a discrete system called CD-4 while recording industry rival CBS beat the drum for its SQ technology, which matrixed signals. At the same time, Sansui promoted its own QS.

THE FUTURE OF AUDIO

"High fidelity is a serious hobby to those who pursue it," Mac McProud wrote in conclusion to his 20th anniversary retrospective, published a quarter century ago in these pages. "These audio buffs put a lot of time and money and heart and soul into it, and they expect a lot of satisfaction in return. We at Audio have the same hobby, really, and we enjoy being of whatever help we can to our fellow hobbyists. So we pledge...to carry on in the same vein improving whenever we can, but always trying to help the reader." To this, on the occasion of our 45th, we add a sonorous Amen.

WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO KITS?

"The innovations which came after our 15th anniversary [in 1962] include some marvelous improvements in kit packaging," editor C.G. McProud recounted in a long, retrospective article published in 1967 to mark Audio's 20th. At that time, McProud pointed out, Harman-Kardon took to employing "some pretty fancy cardboard-box containers which made it easy for the novice to identify the parts in the order in which they were to be used. Scott led with instruction books in which the actual colors of the wires appeared in the diagrams" while "Fisher's innovation appeared in the form of a soft plastic bag packed with a number of bits and pieces which would be used for the steps on a given page of the instruction book." Exactly 30 years later, in 1992, the audio kit industry experienced a cataclysm so momentous that it was commemorated not in a hobbyist journal but on the front page of the New York Times. Heath, long a leader in the business, closed its doors.

EPILOGUE

by Gene Pitts III, Editor

Gene Pitts (left) has been Audio's Editor since 1973.

Very few magazines last as long as 45 years, and I believe it is a gauge of the strength of our industry (or is it our collective mania?) that Audio is so much stronger now than when we began. Still, we are a relatively esoteric magazine, and the peculiar language we speak-half science and at least one quarter a jargon specific to our cult-is the price of admission.

Oddly, for us at least, there is at least as much joy in the equipment as in the music it makes. There is, as well, a curious pride of ownership of very physical and expensive pieces of electronics, which are ultimately judged in a very personal way, despite what the measuring meters say.

Audio's first Editor, John Potts, said it quite appropriately: If it measures well and sounds good, it is good. But if it measures well and sounds bad, it is bad. I would add only this--that we put science in the service of listening. Because it's all too easy to listen with our dreams and not our ears.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Sept. 1992)

Also see:

Listening and Experience (Aug. 1992)

The Audio Interview--Goddard Lieberson--A Classic at Columbia (Sept 1992)

= = = =