The minds and inventions of the two geniuses tended to come into contact -- and even conflict.

by James A. Drake

THE CITY of Mount Clemens in Macomb County, Michigan, lay about a third of the way along the Grand Trunk railway line that, in the middle of the nineteenth century, linked Detroit with Port Huron. One day in August 1862 the three-year-old son of the Mount Clemens station agent, J. U. Mackenzie, was playing on the tracks, unaware that a boxcar for a waiting passenger -freight train was being shunted to the main line from a nearby siding. As the boxcar rolled toward him, he was pulled from its path by a fifteen-year-old candy vendor who had gotten off the train to stand on the platform until the switching was finished. The grateful station agent asked what he could do to re pay the youth. In response, Thomas Alva Edison said he would like to learn telegraphy. Mackenzie put Edison up at his home and taught him the rudiments in a matter of weeks. Within a year, Al-he was known by the short form of his middle name became the peer of any telegrapher along the Grand Trunk line.

In 1863, word reached Mount Clemens about an other exploit of the candy-vendor-turned-telegrapher, then working in his home town, Port Huron. The telegraph cable linking Port Huron and Sarnia, Ontario, across the St. Clair River, had bro ken during an ice jam, and Al Edison improvised an emergency communication system by using a locomotive whistle to send Morse code messages across the river. He was a hero in his hometown, and his name became known all along the Detroit - Port Huron run. In a mere fourteen years his name would be known throughout the world.

A little more than 100 miles east of Port Huron, a Scotch settlement prospered near the city of Brantford, along the Grand River in southern Ontario. One of Edinburgh's most respected families, the Bells, had emigrated there after Scotland's "white plague" of the 1850s. Alexander Melville Bell, the family patriarch, had lost two of his sons to the plague, and he feared for his third son, who had been exposed to the disease but whose health ...

[James A. Drake is collaborating with Edward S. Clute on a book about recording's first one hundred years. ]

... improved because of the more favorable Canadian climate. Alexander Graham Bell II bore the name of his grandfather, one of the most important of the founders of the science of speech pathology.

His first job was as a teacher of "visible speech"- a sign language for deaf mutes invented by his father-to Mohawk Indians in the Brantford area. In the early 1870s, he taught in Boston, but soon his interest turned to the improvement of the tele graph. He tried to develop a workable "harmonic telegraph" by which several messages could be transmitted over the same line. The device he worked on throughout the year 1875 was a tele graph transmitter that could be tuned to a variety of musical pitches, on any one of which the Morse code dots and dashes could be sent electrically. A second device coupled to the first could receive the coded messages, so long as it was tuned to the same musical pitch. In the Charles Williams electric shop at 109 Court Street, where he conducted his experiments, Bell's monastic existence and secretive ways branded him a loner. He had good reason to be secretive about his work; he was one of several experimenters working on essentially the same idea.

Edison, who was exactly Bell's age, was also at work on a variant of the harmonic telegraph, though he was not as absorbed by it as Bell was.

After a five-year stint as a roving telegrapher and experimenter, Edison had finally hit upon what was, in his view, a useful idea-he called it an electric vote recorder. He was granted a patent in 1869, only to see the legislators and representatives he had hoped to serve show almost no interest in the device.

More angry at their cavalier attitude toward efficiency than hurt by their rejection, he set to work on a second invention whose market would be guaranteed. In 1870, not long after his twenty-third birthday, Edison signed a contract with the Gold and Stock Telegraph Company for his universal stock printer, an improved ticker device, and was paid $40,000. It was the first money he made from an invention and a salve to his frustrations. He used the money to build a combination laboratory and production plant in Newark, New Jersey, where he stayed until the spring of 1876. Then he moved to much larger quarters in Menlo Park, a short distance away, where the luxury of time, money, and a handful of assistants enabled him to let his fertile mind wander in the still uncharted territory of applied electricity.

Bell, during the same years, had no such luxury.

His mind was more limited in scope than Edison's, although the two shared much otherwise. Both were almost entirely self-taught in physics and electricity ( Bell had a formal background in acoustics). Both were physically rugged, favored with constitutions needing little or no exercise to maintain. Early in life Edison had conditioned himself to sleep soundly for three or four hours at a time and then to work twelve to sixteen hours or more without any significant break. Bell's periods of sleep were longer, if equally irregular, yet he shared Edison's capacity for exhausting everyone around him. It was during one of these marathon sessions in the summer of 1875 that Bell's assistant, Thomas A. Watson, witnessed the birth of the tele phone. "On the afternoon of June 2, 1875, we were hard at work on the same old job, testing some modification of the [telegraph] instruments," Watson recalled in an address before the Telephone Pioneers of America in 1913. "Things were badly out of tune that afternoon in that hot garret, not only the instruments, but, I fancy, my enthusiasm and my temper, though Bell was as energetic as ever." As was the custom in their experiments, Watson took charge of the transmitters, and Bell manned the receivers in an adjoining room. After tuning the devices, the two would attempt to transmit messages and improve their design in the process.

On that June afternoon Watson was plucking the springs of a transmitter disinterestedly. One spring gave him trouble. "It didn't start, and I kept on plucking it, when suddenly I heard a shout coming from Bell in the next room, and then out he came with a rush, demanding, 'What did you do then? Don't change anything. Let me see!' " On examining the transmitter they found that the spring's contact points had become welded together, allowing a steady electrical current to flow between the transmitter and receiver. The current had carried the faint impulse of the vibrating spring into the receiving instrument Bell had pressed to his ear. As Watson was to say of the event nearly forty years afterward, "The right man had that mechanism at his ear during that fleeting moment and instantly recognized the importance of that faint sound thus electrically transmitted." When Bell was granted a patent on his "speaking telegraph" (the word "telephone" came later), Edison was one of several electricians who had been close to achieving what Bell did. Edison continued his analytical interest in the telephone, and in less than a decade the Patent Office was to grant him nearly forty patents on his improvements for Bell's device.

------------

*This, the traditional view of Edison's sleeping habits, is challenged-at least as it applies to his later years-by Ernest Stevens, his long-time pianist and arranger. in " Edison as Record Producer" elsewhere in this issue.

------------

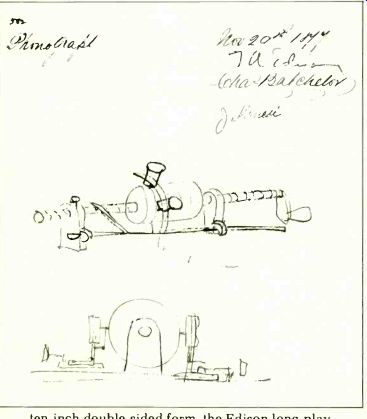

His work on one of these improvements, if his laboratory notes accurately reflect his thought and experimentation, ultimately led him to the phono graph in midsummer 1877. On July 18 he asked his assistants, Charles Batchelor and James Adams, to sign a page of notes titled "Spkg (Speaking) Tele graph," which included a paragraph containing the inventor's usual abbreviated and often idiosyncratic spellings:

Just tried experiment with a diaphragm having an embossing point & held against para finn paper moving rapidly. The spkg vibrations are indented nicely & theres no doubt that I shall be able to store up & reproduce automatically at any future time the human voice perfectly.

By the last week of November 1877 Edison had thought out the concept of recording sufficiently to commit final designs to paper. [For a more detailed account of the interim, see "Recordings Before Edison" elsewhere in this issue.]

----------

above: The photo at far left shows Edison in 1861, aged fourteen, a year before his feat of bravery made him a local celebrity. Alexander Graham Bell is shown as he appeared in 1876, a year after the invention of the telephone.

-------------

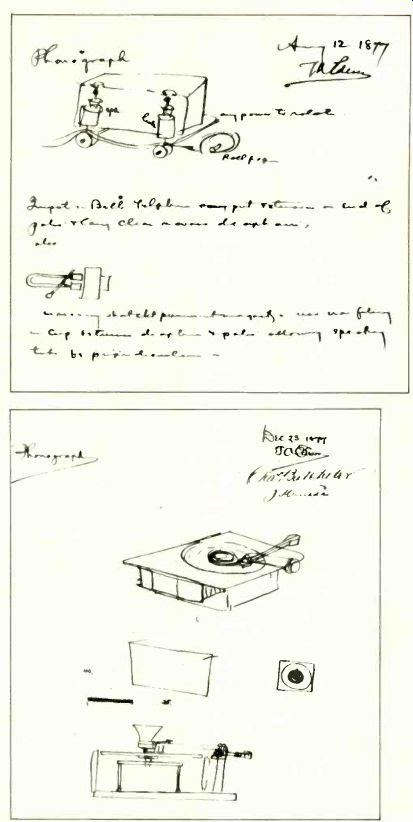

On November 29 he asked Batchelor and John Kruesi, one of his best model-makers and most trusted associates, to wit ness a carefully drawn sketch. Then he instructed Kruesi to make a working model immediately.

Whether Edison worked on the construction of the model is not definitely known, but Batchelor noted on December 4 that Kruesi had made the phonograph and, two days later, that he had fin ished it. Edison put a tinfoil sheet around the ma chine's hollow cylindrical drum, the surface of which had a continuous spiral groove etched into it. The drum was hand -powered by a small crank, the shaft of which had been threaded so that the supports and bearings holding it allowed it to move laterally. On either side of, and at right angles to, the drum were two similar -looking brass housings, each with a diaphragm on its inner face.

Pin-shaped styli protruded from the centers of each diaphragm and could be moved toward the drum and brought into contact with its foil coating by means of a knob and set-screw arrangement.

One of the housings, that for recording, had a mouthpiece attached to it. Edison moved the recording stylus into position against the foil, cranked slowly, and recited "Mary had a little lamb" into the mouthpiece. A series of indentations was embossed into the foil by the sound vibrations. Moments later, after adjusting the reproducing stylus and again turning the crank, he heard the nursery rhyme repeated to him. A year afterward he was to say of the event, "I was never so taken aback in my life--I was always afraid of things that worked for the first time." He was granted a patent on February 19, 1878, seven weeks after he had applied. None of the examiners and staff members had ever seen anything like it. What must have struck everyone in those early years was the utter simplicity of the device.

Reporting on it in March 1878, a Harper's Weekly editor told his readers that "it was rather startling to find in the famous phonograph a simple apparatus, which, but for the absence of more than one cylinder, might have been a modern fluting ma chine." Unlike the telephone, it did not depend on an assemblage of batteries and wires, and unlike most other Edison patents of the same period, it was completely nonelectrical.

The principle of the phonograph was almost as simple as the machine embodying it. Edison's own description of the essence of phonograph recording and reproducing was set forth in his two -page patent application:

The invention consists in arranging a plate, diaphragm or other flexible body capable of being vibrated by the human voice or other sounds, in conjunction with a material capable of registering the movements of such vibrating body by embossing or indenting or altering such material....

In the application Edison clarified the concept and design of the phonograph in more expansive ways than he has sometimes been credited with. In one section he described, for example, a process for mass-producing metal foil recordings using plaster-of-paris molds-a process "valuable when musical compositions are required for numerous machines." This early vision of inexpensive copies of musical performances contradicts the charge usually leveled at Edison: that he was opposed to the use of the phonograph as a medium of entertainment. He also described ways of recording and re producing sounds on discs and on tape, both "by indentations" and "in a sinuous form, .. . laterally

... to the right and left of a straight line." And while he was still thinking in terms of tin foil as the best recording surface, it is apparent that he had thought well beyond the immediate results of his laboratory experiments. During the first few months of the phonograph's existence, Edison wrote an article for the North American Review's June and July editions. It listed a number of potential uses of the phonograph-most of them realized within Edison's lifetime. He saw his phonograph as, first, a means of letter -writing without the aid of a stenographer. He foresaw its use in music boxes and toys, of "phonographic books which will speak to blind people without effort on their part." He saw it as an adjunct to classroom teaching, and especially in the teaching of elocution and foreign languages. He also saw the phonograph being linked with the telephone, "so as to make that instrument an auxiliary in the transmission of permanent and invaluable records, instead of being the recipient of momentary and fleeting communication." Rarely has an inventor been so remarkably far sighted in predicting the future of an idea. He and his phonograph company played a dominant role in the first three decades of commercial recording.

Even after his company's influence had waned, his name was to be associated with the Ediphone and similar dictating equipment. His own Telescribe, one of the early telephone recording devices, was a forerunner of the automatic answering services now in use.

Of Edison's contributions to the evolution of the phonograph, perhaps none is more intriguing than his pioneer work on long-playing records. In the middle 1920s, when the introduction of electrical recording gave the two giants of the industry, Vic tor and Columbia, a gaping lead over Edison in the marketplace, he became fascinated with the prospect of recording music in prolonged, uninterrupted portions. Though he was nearing eighty, his incomparable drive and inventive genius once again yielded a fascinating dividend. Pressed in ten -inch double -sided form, the Edison long-playing discs of 1926 had a listening time comparable to the modern LP-but at 80 rpm, rather than 33 1/2.

------

Edison's note pages in 1877 demonstrate the fecundity of his mind as it expanded the "speaking telegraph" idea of July 18 to encompass cylinder, disc, tape, and even a type of magnetic recording. In the August 12 sketch, a paper tape is embossed by a pin attached to a vibrating diaphragm (marked "spk") while a similar "listen" device picks up and reproduces the sound. That he was still thinking in terms of Bell's telephone is evident from his comment below the sketch: "Input is Bells Telephone. Put extensions on end of poles & carry clear across diaphram." Beneath that is a magnetic concept, with the notation: "in mercury short ckt permanent magnet = use iron filing in cup between diaphram & poles allowing speaking tube be perpendicular." August 12 was also the date on a bogus "original" sketch of Edison's invention. (See "Notes to Future Scholars" immediately preceding this article.) The legitimate first sketch, dated November 29, is reproduced below. Edison's disc phonograph and arm design of December 23 are remarkably like record-players of seventy-five years later.

----------

The secret of this remarkable achievement lay in the ultra -fine 1/400 -inch groove cut by the lathe he designed. But the records were a commercial failure.

Edison's long-term involvement with recording lapsed only once, when, in the autumn of 1878, he turned his full efforts to the development of a practical incandescent lamp. After accounts of the tin foil phonograph's early public demonstrations were printed in the spring of 1878, Mrs. Alexander Graham Bell sent Edison a warm personal letter congratulating him on his new invention. Gardiner G. Hubbard, her father, had been a board member in the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company, and through his involvement she and Bell had been able to follow the phonograph's development from its inception. Relations between the two inventors were amicable from the beginning and remained so until Edison filed a patent application on what came to be called the "compressed lampblack button transmitter" in the telephone industry. Edison's transmitter (the forerunner of the carbon microphone) brought Bell's telephone within practical reach of the public because of the improved reception it made possible. But Edison's patent went to Western Union interests, who set up a telephone system. The infant Bell Company was powerless, lacking the capital and the nation wide network of telegraph lines Western Union boasted when it entered the telephone industry.

Late in 1879 Bell defeated the Western Union interests after a year of patent infringement proceedings. In a signed agreement, to extend seventeen years, Western Union agreed to sell its telephone interests to the Bell Company in return for a royalty on each telephone Bell leased. Companion terms were that Bell Telephone would stay out of telegraphy and Western Union would stay out of the telephone field.

In 1880 Bell began to find the kind of support Edison had become accustomed to. That year the French Academy of Sciences awarded Bell and his telephone its Volta Prize for scientific advancement. A cash award of $10,000 was part of the prize, and with the money Bell founded what he called the "Volta Laboratory" in Washington, D.C.

He took two associates for this new enterprise: his cousin Chichester Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter, an electrician and superb instrument designer.

Whatever other aims Bell and his "Volta Associates," as they came to be called, had in founding the laboratory, the reams of notes the three gave the Smithsonian Institution show clearly that the improvement of Edison's phonograph was one of their first priorities. No one knows whether this was prompted by lingering resentment on Bell's part toward Edison for the button transmitter patent. Once they began their work, it did not take them long to identify the Edison machine's main weakness-its tinfoil recording surface. They found a substitute-beeswax-and tried it on a small Edison machine. The player the three deposited in the Smithsonian on October 20, 1881, had a wax -coated recording drum onto which was impressed Hamlet's line, "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your philosophy," followed by "I am a graph-ophone and my mother was a phonograph." In the summer of 1885, five years after they had begun their experiments, the Bells and Tainter applied for patents on their improvements, which included a more effective loosely mounted "floating" stylus and an electric motor for power. (Their application also called for a disc record, but the Bells never took the idea further.) By the time the patents were granted the three already had a prototype of their grapho-phone ready to go into production. The machine their American Graphophone Company manufactured in its Alexandria, Virginia, factory was a hand -powered model having a removable coated cardboard tube for the recording surface.

Some time after production began, Bell and his partners sent a small group of backers to meet with Edison in the hope that he would want to combine efforts to launch an improved, commercially vi able phonograph. Out of respect for the inventor's basic patent, the Bells and Tainter were prepared to abandon the use of the term "graph-ophone" if Edison would agree to join forces. Various sources describe the inventor's reaction to the proposal as ranging from cool to outraged. At any rate, the three abandoned any thought of working with him.

Edison translated his reactions to the graph-ophone into the form he knew best-sheer hard work. Late in 1886 he renewed research on the phonograph while continuing his work on electric lighting systems. Two years later-at 5 a.m. on June 16, 1888-he emerged from his West Orange laboratory with a prototype. He had worked seventy two hours without sleep or breaks of any kind, and, seeing his model in action for the first time, he called for a photographer to capture the moment.

Taken by the light of the rising sun, the pictures show a weary, unshaven forty-one-year -old Edison seated behind an all-wax-cylinder phono graph powered by batteries. It would be the basis on which he would build the Edison Phono graphic Works, Inc.

The tale of the entangled relationship between Edison and Bell has a paradoxical sequel. In 1888, for an investment of $200,000, the Bells and Tainter ceded to a businessman named Jesse H. Lippincott the exclusive rights to sell graph-ophones in the United States. Hardly had he concluded this deal when he approached Edison, who wanted to begin manufacture of his improved phonograph but lacked capital. Lippincott bought Edison's patent rights for $500,000, but left the manufacturing rights-as he had done with the graphophone--in the hands of the inventor. On July 14, 1888, Lippincott formed the North American Phonograph Company, and set up a series of territorial franchises which in effect controlled the entire talking --machine industry in the United States. Edison and Bell were "cooperating" at last.

The harmony was short-lived. Through a series of administrative miscalculations-combined with an inability to see the phonograph's potential as a medium of entertainment--Lippincott brought North American to the verge of insolvency, and in 1891 relinquished control to Edison. The inventor fared little better with the cumbersome setup, declared North American bankrupt in 1894, and was forced to wait for two years to form his own National Phonograph Company for the manufacture and distribution of his machines. One franchise survived the general wreckage of the combined Edison - Bell interests, and rose, phoenix -like, to a position of eminence in the industry within a few years. The Columbia Phonograph Company, located in the District of Columbia, had gotten its start by distributing graphophones, and was to be a thorn in Edison's side. But that is another story.

-------------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1977)

Also see:

The Life and Labs of Thomas A. Edison; Robert Long; An informal pictorial history