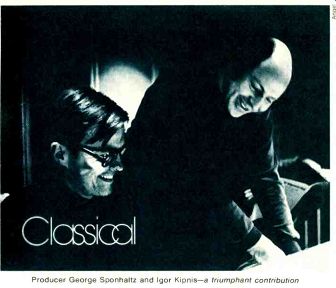

above: Producer George Sponhaltz and Igor Kipnis--a triumphant contribution

BACH: Italian Concerto, S. 971; French Overture (Partita in B minor), S. 831. Igor Kipnis, harpsichord. [George Sponhaltz, prod.] ANGEL S 36096, $6.98.

Though it was Bach himself who first linked these seemingly unrelated works, as Book II of his monumental Clavierdbung series, the only other current disc coupling seems to be Ralph Kirkpatrick's magnificent 1961 Archiv disc (198 032). Thus the way is wide open for Igor Kipnis, his grand Rutkowski & Robinette double-manual harpsichord, and engineer Carson C. Taylor to make a major contribution to the Bach discography-and that's exactly what they do, triumphantly.

There have been many fine recordings of the Italian Concerto showpiece, among them Kipnis' own earlier one (originally for Epic in 1967, now on Columbia M 30231), but his new version demonstrates dramatically how richly he has grown in interpretative maturity as well as in technical authority and pliancy. Yet it is Kipnis' performance of the larger -scaled, more imaginative, and far more profound B minor Partita (both in its expansive opening Overture and in the delectable variety of little dances that follow) that is one of the outstanding achievements, if not the outstanding achievement, of an already outstanding career. R.D.D.

BARTOK: Concertos for Piano and Orchestra, Nos. 1 and 3. Stephen Bishop-Kovacevich, piano; London Symphony Orchestra, Colin Davis, cond. PHILIPS 9500 043, $7.98.

Comparison: P. Serkin, Ozawa / Chicago Sym. RCA LSC 2929

These two piano concertos. Bartok's first and last, are separated by almost twenty years, and the differences are considerable.

The First Concerto, completed in 1926. is a percussive, rhythmically driving, and at times sharply dissonant composition. Texturally and formally it shows the com poser's preoccupation with baroque key board music: lean, linear writing with a pronounced hint of the eighteenth-century concertante style. (Interest in eighteenth-century music was, of course, widespread in the 1920s. But in Bartok's case it is particularly significant. as he brought out editions of keyboard music by Couperin and Scarlatti, as well as transcriptions of works by a number of other baroque composers.) The Third Concerto is a very different matter. One of Bartok's last works, com posed in 1945, it displays a remarkable delicacy. In place of the brusqueness of the earlier concerto is a lyrical serenity that pervades the entire composition. Formal balances are almost classical in nature, and the keyboard writing features gentle figurations that cover much of the piece with lacy filigree.

Bishop-Kovacevich and Davis seem more in tune with the later work, which they per form with unusual sensitivity and musicality. Especially striking is the opening dialogue between strings and piano in the second movement, which, though taken quite slowly, is beautifully sustained.

(Bishop-Kovacevich plays his responses pianissimo, thus matching the dynamic level of the strings, although Bartok calls for piano: but I personally find the result quite satisfying.) The First Concerto is less good, mainly because it lacks the aggressive rhythmic quality the score demands. Yet there are some marvelous moments (again, the slow movement is especially fine), and the general level of playing, both orchestral and pianistic, is good.

An interesting comparison for this coupling is the Peter Serkin/Ozawa /Chicago Symphony version on RCA. The performances there are much more individual than the present ones: The playing is more differentiated, and the textural components, especially in the orchestra, are more clearly separated. Tempos are a bit slower, which results in some heavy-handedness in the Third Concerto. But in the First, despite the more relaxed pacing, Serkin and Ozawa achieve more rhythmic bite than do Bishop Kovacevich and Davis. R.P.M.

reviewed by:

ROYAL S. BROWN ABRAM CHIPMAN R. D. DARRELL PETER G. DAVIS SHIRLEY FLEMING ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN KENNETH FURIE HARRIS GOLDSMITH DAVID HAMILTON DALE S. HARRIS PHILIP HART PAUL HENRY LANG ROBERT LONG IRVING LOWENS ROBERT C. MARSH ROBERT P. MORGAN JEREMY NOBLE CONR AD L. OSBORNE ANDREW PORTER H. C. ROBBINS LANDON HAROLD A. RODGERS PATRICK J. SMITH SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

BEETHOVEN: Sonatas for Piano: No. 30, in E, Op. 109; No. 31, in A flat, Op. 110. Maurizio Pollini, piano. [Rainer Brock, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 645, $7.98.

As might be expected from Pollini, these performances are remarkable in their sheer musical and technical control. Some might think that control at times too great, but I am fascinated by the occasional signs, particularly in Op. 109, that Pollini may be loosening his ironclad self-containment.

In the Prestissimo second movement of Op. 109, taken at a commendably spanking clip, one immediately discovers some bending of the rhythmic pulse for the purpose of intensifying harmonic and structural felicities. This device has been used to splendid effect by such great artists as Schnabel, Fleisher, and Toscanini, and I am particularly happy to hear Pollini relenting from his accustomed microscopically exact translation of every ratio and note relation ship.

----

Explanation of symbols

Classical

Recorded tape:

Budget

Historical Reissue

Open Reel

8 -Track Cartridge

Cassette

------------

Surrounding this superbly energetic scherzo are a first movement made arresting by a less contrasted difference than usual between the opening tempo and the adagio that follows in the secondary thematic group, and a set of variations whose tempo remains a good, swiftly flowing con moto. Pollini's clarity in the fugal variation and in the treacherous final variation with the trills, leaps, and runs is every bit as impressive as Charles Rosen's ac count (Columbia M3X 30938) and far more colorful and natural sounding than in that formidably intellectual but mostly prosaic rendering. Not a conventional Op. 109, then, but one of all-round distinction that should give lasting satisfaction.

Op. 110 is not quite as stimulating, but it too shows a bit more passion and color than Pollini's Carnegie Hall account two years ago. The opening movement, as in Graffman's recent recording (Columbia M 33890, September 1976), is supremely disciplined and intelligent, yet slightly too businesslike. The scherzo is more strongly characterized than Graffman's, with big contrasts and full, galvanic fortissimo chords. The difficult rising legato octaves in the bass line are consummately smooth, the silent bars as precisely gauged as Graffman's but with an added touch of vehemence. The recitativo, however, is disappointingly glib. The first arioso is better than the second, in which Pollini sounds too healthy at the points where Beethoven indicates a lessening of energy. The fuga is even faster than Graffman's, which I al ready thought uncomfortably brisk, but the return is fairly impressive. Pollini gives more stress and activity to some of the sub ordinate accompanimental voices at the end than he did at Carnegie Hall, and there is more nuance and color than in that performance or in Graffman's recording. If not the ultimate Op. 110 (among recent recordings I prefer Ashkenazy's, London CS 6843, and Brenda Philips 6500 762), it nevertheless is a strong contender.

DG's sound is solid but disquietingly plangent in the treble. Also, to judge from the central trio in the second movement of Op. 110, Pollini is joining that company of moaners, singers, grunters, and heavy breathers. H.G.

BERLIOZ: Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14. Orchestre National de l'ORTF, Jean Martinon, cond. [Rene Challan, prod.] ANGEL S 37138, $6.98 (SO -encoded disc). Tape: 4XS 37138, $7.98.

Though this Fantastique yields in virtuos ity, clarity, and sonics to the remakes of Karajan (DG 2530 597, February 1976) and Davis (Philips 6500 774, May 1975), its probity and musicianship carve a niche very near the top of the list.

Martinon makes the same textual choices as Klemperer (Angel S 36196): He uses the supplementary cornets in the second movement and observes the first -movement re peat (but not that in the " Marche au suppuke"). His way with the score, however, is more akin to Monteux's than to Klemperer's. He favors a sedate, magisterial lyricism that is quite capable of erupting into impressive force. The occasional impetuous speedups in the basically steady " Marche au supplice" and "Witches' Sabbath" particularly recall Monteux's no nonsense flexibility of tempo. The unsentimental ardor of the symphony's opening, the unpretentious phrasing of the fermatas in "Un bal," and the rugged shaping of the "Scene aux champs" also recall Monteux's splendid and lovable musicianship. (The "Scene" is unfortunately split between sides, just after the appearance of the Wee fixe-the rather deliberate tempos probably left little choice.) Regrettably, Martinon also follows Monteux in eschewing the ghoulish woodwind glissandos at the be ginning of the last movement.

There is nothing wrong with the playing of the Orchestre National; it is simply out classed by Karajan's Berlin Philharmonic and Davis' Concertgebouw (whose E flat clarinets are unsurpassed for raunchiness in the "Witches' Sabbath" transformation of the idee ft/re). The rather high-pitched chimes are powerful, the drums excellent.

The sound is generally round and attractive, but a shade too much ambience inhib its articulation, rendering the bass line a bit amorphous and making the low brasses overly reticent in the " Marche." The high brasses, however, are just fine in the "Witches' Sabbath."

- H.G.

Burzsvent The Airborne Symphony. Orson Weiles, narrator; Andrea Vets, tenor; David Watson, baritone; Choral Art Society; New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein, cond. [Thomas Z. Shepard, prod.] COLUMBIA M 34136, $6.98.

Whatever happened to Marc Blitzstein? Time was when he stood in the forefront of American composers, when his name was mentioned in the same sentence as Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson. Since his death in 1964, he has been (like Leo Ornstein) forgotten. If he is remembered at all, it is for his stage works: The Cradle Will Rock (1937), Regina (1949), and especially his adaptation of the Weill -Brecht Three-Penny Opera. Now, out of the blue, Columbia releases in its "Modern American Music Series" one of Blitzstein's least -known works, The Airborne Symphony, newly re corded with Orson Welles and Leonard Bernstein, who gave the piece its world premiere on April 1, 1946, participating.

In 1943, when Blitzstein was a sergeant in ...

--------

Critics’ Choice

The best classical records reviewed in recent months.

BACH: Concertos for Harpsichord(s) and Strings. Leppard. PHILIPS 6747 194 (3), Dec.

BACH: Concerto Reconstructions (ed. Hogwood). Marriner. ARGO ZRG 820/1, Dec.

BACH: Violin Partite No. 2; Sonata No. 3. Chung. LONDON CS 6940, Oct.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 7. Ferencs k. HUNGAROTON SLPX 11791, Dec.

BEETHOVEN: Triple Concerto. Suk, Chuchro, Panenka; Masur. SUPRAPHON 1 10 1558, Oct.

BEETHOVEN: Violin Concerto. Suk; Boult. VANGUARD EVERYMAN SRV 353 SD, Oct.

BEETHOVEN: Violin Sonatas (10). Suk, Panenka. SUPRAPHON 1 11 0561/5, (5), Oct.

Bair: Carmen. Troyanos, Domingo, Van Dam; Solti. LONDON OSA 13115 (3), Dec.

BRAHMS: Piano Sonata No. 2; Paganini Variations. Arrau. PHILIPS 9500 066, Dec.

Bauman: Requiem in D minor. Beuerle. NONESUCH H 71327, Nov.

CHOPIN: Preludes, Opp. 28, 45, posth. Perahia. COLUMBIA M 33507, Nov.

CHOPIN: Preludes, Opp. 28, Pollini. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHONE 2530 550, Nov.

DEBUSSY: Etudes. Jacobs. NONESUCH H 71322, Oct.

Dvorak: Quartets, Opp. 96, 105. Prague Qt. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 632, Dec.

FELDMAN: Various Works. Various performers. ODYSSEY Y 34138, Dec.

GERSHWIN: "Gershwin Plays Gershwin." RCA VICTROLA AVMI-1740, Dec.

Grieg: Orchestral Works, Vol. 1. Abravanel. Vox QSVBX 5140 (3), Nov.

Leharr: Merry Widow Ballet. Lanchbery. ANGEL S 37092, Nov.

MOZART: Haffner Serenade. De Waart. PHILIPS 6500 966, Nov.

Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition; B flat Scherzo; Turkish March. Beroff. ANGEL S 37223, Dec.

NIELSEN: Saul and David. Christoff; Horenstein. UNICORN RHS 343/5 (3), Nov.

ORFF: Carmine Burana. Casapietra, Hiestermann, Stryczek; Kegel. PHILIPS9500040, Dec.

Schubert: Sonata for Piano, D. 850; Landler (4). Ashkenazy. LONDON CS 6961, Dec.

SCHUMANN: Frauenliebe and Leben.

SCHUBERT;BRAHMS: SONGS. Baker, lsepp SAGA 5277, Nov.

Strauss, R.: Horn Concertos. Damm; Kempe. ANGEL S 37004, Nov.

CARUSO: Legendary Performer. (Soundstream re-processings.)

RCA RED SEAL CRM 1-1749, Nov.

----------------

... the Eighth Air Force stationed in England, he got the idea of writing a large symphonic work evoking the history of human flight.

The Air Force liked the idea and commissioned him to write it. He began the work in London, and by the time he was almost through he was suddenly recalled to the States--so suddenly that he forgot to take the score with him. It was supposed to follow him by mail but didn't. Meanwhile, he played part of it from sketches for Bernstein and got a commitment for a performance. So he began rewriting The Airborne.

"When I had completed three-fourths of the score for the second time," Blitzstein later wrote, "the original score arrived one fine day in February 1946. To my amazement, I found that the new score was precisely at the same point at which the original had been when I left Europe. And I did feel that the second version was better than the first." The Airborne met with a cordial reception from the press. Writing of the premiere in the New York Times, Olin Downes re ported: "Not often has a new symphony had such an approving reception in this city. The work gripped the audience by its subject and its musico-dramatic treatment." In 1977, only thirty years later, the work sounds like an antique. The text is embarrassingly pompous and melodramatic, echoing the bombastic style of Norman Corwin's radio shows. Was there really a time when this sort of adolescent enthusiasm genuinely gripped us? These days, I doubt that many people will be stirred by The Airborne. But if you listen to it as a period piece, as an echo of an earlier time, it may evoke those days when a phrase like "Open up that second front!" had both meaning and emotional impact. I L.

BRAHMS: Ballades (4), Op. 10; Fantasies (7), Op. 116. Emil Gilels, piano. [Gunther Breest, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 655, $7.98.

BRAHMS: Piano Works. Bruce Hungerford, piano. [Joanna Nickrenz, prod.] VANGUARD VSD 71213, $6.98.

Ballade in D minor, Op. 10, No. 1 (Edward); Capriccio in B minor, Op. 76, No. 2; Intermezzo in A, Op. 76, No. 6; Rhapsodies (2), Op. 79; Intermezzo in B flat minor, Op. 117. No. 2; Pieces (6). Op. 118.

The Gilels disc may be the first installment in a cycle of Brahms's smaller piano works (I am sorry to see Kempff's DG series disappearing from the catalogue): the Hungerford program is a generous sampler that serves to remind us that this Beethoven specialist can play other composers as well (a Chopin recital, VSD 71214, was reviewed in December 1976).

The two pianists share a certain tempera mental--or perhaps tonal--kinship. Neither is particularly interested in the comfort able, broad, expansively sonorous approach to Brahms exemplified by the late Wilhelm Backhaus. With these artists, nervous tension is more highly prized, along with a tonal palette that might be likened in culinary terms-to rare, lean steak. There is a bright edge, a distinctness of inner voices. Moreover, the slender framework, while not slighting harmonic structure, tends to be tilted less toward the bass register. Hungerford inclines more to sanguinary wildness in his readings, with a use of fiery rubato and thrusting accent to drive his many points home. Gilels, though certainly not tame, is a shade more detached emotionally, more content to let the music speak without altering or intensifying the rhythmic patterns. I found Gilels particularly impressive in the ballades, which have a smoothness of texture and warmth of feeling not always found in his work.

Deutsche Grammophon's piano reproduction-sleek as well as cutting--has it all over Vanguard's, which again sounds like a close pickup overlaid with artificial reverberation.

- H.G.

BRITTEN: Sinfonia da Requiem, Op. 20. Peter Grimes: Four Sea Interludes, Op. 33a; Passacaglia, Op. 33b. London Symphony Orchestra, Andre Previn, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.] ANGEL S 37142, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

A greatly matured Previn demonstrates what better justice he can now do to Britten's early Sinfonia do Requiem than he was able to do in his 1964 Columbia recording with the St. Louis Symphony (a version incongruously coupled with Copland's Red Pony Suite, as it still is in the Odyssey Y 31016 reissue). But probably just because he is trying too hard to prove his new powers (as indeed Britten himself was trying too hard in 1940 when he wrote so ambitious a score), this far more authoritative orchestral performance only intensifies the lugubrious and melodramatic aspects of Previn's reading.

The present couplings are far more appropriate than before: the Peter Grimes "Sea Interludes" and "Passacaglia," which were so influential in establishing Britten's fame worldwide, but which seem to have been somewhat neglected in recent years.

They too are somewhat over-insistent and portentous at times, though Previn is successful in dramatically evoking the mood and pictorial potentials of these salty wind blown scenes.

As. interpretations, the composer's own still remain unchallenged: the Sinfonia on London OS 25937 of 1965, the Peter Grimes excerpts either in the complete opera set of 1960 or separately on London CS 6179. But Previn's versions benefit incalculably, in both scoring authenticity and atmospheric effectiveness, from present-day technological advances, which ensure arrestingly vivid and wide -range sonics in stereo-only playback, even more expansive and evocative magic in quadriphonic play back. R.D.D.

Bruckner: Symphony No. 7, in E. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Jascha Horenstein, cond. UNICORN UNI 111, $6.98 (mono) [from POLYDOR originals, re corded 1928] (distributed by HNH Distributors, Box 222, Evanston, Ill. 60204).

The Bruckner Seventh Symphony has be come fertile ground for antique collectors.

Hard on the heels of Oskar Fried's acoustical recording (Bruno Walter Society BWS 719) and Oswald Kabasta's 1942 Munich Philharmonic recording (EMI Odeon 1C 053 28981) comes Unicorn's reissue of Jascha Horenstein's 1928 Berlin version, the first electrical recording of a complete Bruckner symphony. (Fortunately the Seventh has no serious textual problems to disqualify the older performances.) Despite severe sonic limitations-considerably better orchestral definition was being achieved in 1928 in Amsterdam and Philadelphia--the work of the young Horenstein warrants careful attention, and the imagination will fill in the gaps in the (pleasant enough) sound.

Horenstein drew from the Berlin Philharmonic playing that is always gracious and warmly musical, and in each phrase he knew exactly where he had come from and where he was going. Some modern tastes will have to adjust to the abundant portamento, yet there is nothing heavy, cloying, or pompous here. The first movement, too often made episodic by clumsy gear changes, is seamlessly unified in conception, yet without undue sense of hard-driving forward pressure. The Adagio is deep and long -breathed in its serenity and humanity. The last two movements are light and mercurial. Already in 1928 the conductor displayed the qualities that would much later win him broad recognition as a profoundly serious artist who abhorred sensational effects and allowed music to unfold simply and with unobtrusive refinement.

Unicorn has taken great pains over this LP transfer, corralling 78 copies from all over the world to pick the quietest surfaces for each side and hunting down former Berlin Philharmonic players to determine the orchestra's 1928 tuning pitch. The sound that emerges is un-gimmicked and authentic, and the 78 side breaks are smoothly handled. Unfortunately the LP break comes at an exceedingly awkward mid-phrase point (bar 137 of the Adagio), which was not even interrupted on the 78s. One need only move a few measures in either direction to find a better break.

It should go without saying that this is not meant to serve as one's only Bruckner Seventh. Rosbaud's (Turnabout TV -S 34083), rather like Horenstein's in its shy fervor, is easily the best buy in stereo, though it too falls short of the highest technical standards of its era. For an uninterrupted Adagio, one must turn to the three-sided versions, among which the most ex citing and authoritative performance is Haitink's (Philips 802 759/60, with the Te Deum), which is impressively recorded as well.

-A.G.

CHERUBINI: Quartets for Strings. Melos Quartet. [Andreas Holschneider and Rudolf Werner, prod.] ARCHIV 2710 018, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Quartets: No. 1, in E flat; No. 2, in C; No. 3, in D minor; No. 4, in E; No. 5, in F; No. 6, in A minor.

In a quiz contest, this recording would test the most discriminating ears, but puzzles almost as great would remain if the composer's name were revealed.

It is impossible to range Cherubini's quartets in any definite category, because this earnest and reserved composer never permitted any style or trend to dominate him. Born one year after Handel's death, and dying when Schumann was composing his First Symphony and Wagner his Flying Dutchman, during his long life he experienced the great stylistic changes from rococo to Romanticism and was personally acquainted with Gluck, Haydn, and Beethoven, as well as with many of the early Romantics. He watched and studied everything, then went his own way. We might say that his magnificently fluent and never bookish counterpoint found its point of departure in baroque polyphony, but his strong architectural sense and his basic musico-dramatic gifts are perhaps closest to what we call the Viennese School.

Cherubini's main field was church music and opera, which in those days formed one great family of dramatic music. His chamber music he wrote late in life. The first of the quartets, recorded here, dates from 1814, his fifty-fifth year and, significantly, after his stay in Vienna; the second followed fifteen years later; and the sixth and last one he wrote at the age of seventy seven. All of them are masterfully com posed; from Haydn to Schumann every composer, even cantankerous Beethoven, had only boundless admiration for Cherubini's craftsmanship, notably for his luminous part-writing, for indeed he was a composer's composer.

That, of course, has its drawbacks. Except for his church music and some of his operas, Cherubini is not immediately accessible to the layman, as the music often impresses more by its impeccable design than by its communicative force. He likes a rhapsodic style, inserting many small epi sodes in his sonata structures-some of them a bit too long, but almost always coerced into an organic form. This procedure is in fact a personal style, and the op position and/or juxtaposition of contrasts in pace, melody, harmony, and rhythm never fails to fascinate musicians.

The quartets have strong cyclic unity, and Cherubini often bases an entire work on the slow introduction to the first movement. The manipulation of the motivic material, the bold modulations, and the ever changing dynamic shadings are continually interesting, and though his dramatic nature is always in evidence, so is his stylistic sense; everything is always in chamber music terms. (The one exception is the Second Quartet, which is a transcription of his only symphony, a fine work that does not come off as well reduced to chamber music.) At times one is a little impatient with this enigmatic loner: either he does not know when to end a movement, which is unlikely, or he is so eager to nail down the tonality unequivocally that cadence follows cadence and the closing formulas are repeated beyond their desert. Also, while he has many engaging Italianate melodies and he is no stranger to French piquancy, many of the melodies are cool, though all of them are admirably suitable for development.

Cherubini's vitality is amazing. He was seventy-four when he composed his Third Quartet, in D minor, one pf the best in the lot, but the next three are uneven; the invention begins to lag, and he falls back on his prodigious technique. In the last quartet (1837), the aged composer, by now oblivious of the world and writing just for him self, obviously tries what so many composers after him have tried: to make sense of and come to terms with Beethoven's last quartets. Like almost all the others, he could not rise to those hallucinatory heights.

The Melos Quartet consists of able and well-trained musicians who can take the considerable virtuosity demanded by these compositions in their stride, but their approach is a bit too aggressively muscular - propulsive. Wilhelm Melcher, the first violinist, often slides, a practice that, aside from being an annoying mannerism, hurts the articulation of a nice melody. However, the quartet plays with genuine enthusiasm, the ensemble work is good, and so is the sound. Archiv has filled a lacuna with this release, and since the scores are readily available (Eulenburg), inquisitive music lovers will benefit from the study of these interesting works. P.H.L.

GIBBONS: Madrigals and Motets-See Recitals and Miscellany: Consort of Musicke.

GLUCK: Operatic Arias. Janet Baker, mezzo soprano; English Chamber Orchestra, Ray mond Leppard, cond. PHILIPS 9500 023, $7.98. Tape: 00 7300 440, $7.95.

Orfeo ed Euridice: Che puro ciel, Che faro senza Euri dice. La Rencontre imprevue: Bel inconnu; Je cherche a vous faire. Alceste: Divinites du Styx. Paride ed Elena: Spiagge amate; Oh, del mio dolce ardor: Le belle imma gini; Di to scordarmi. Iphigenie en Aulide: Vous essayez en vain.... Par la crainte; Adieu, conservez dans votre ame. Armide: Le perfide Renaud. Iphigenie en Tauride: Non, cet affreux devoir.

Anything that Janet Baker chooses to record is an occasion for joy, and, if my own rapture is just a little modified this time, this is at least partly because Gluck's operas (as Burney sagely remarked) do not lend themselves to being excerpted. The whole neoclassical ideal embodied in his "reform" operas is so concerned with balance, shape, continuity, and contrast that a single aria, even so famous a one as "Che fare?", inevitably loses much of its effect by being taken out of context.

To some extent the planners of this record have tried to compensate by providing contrasts of their own: The big arias from Armide (the forsaken enchantress' farewell to life and love), from Iphigenie en Tauride (in which the heroine proudly rejects her sacrificial duties), and from Al ceste (in which she resolves to sacrifice her life for her husband) are separated by the more lyrical pieces from the other Iphi genie. On the second side the two charming little airs (originally sung by different characters) from the last of Gluck's French op eras-comiques are followed by a group of four of Paris' arias from one of the least-known of his mature Italian operas, and his last collaboration with Calzabigi, Paride ed Elena.

The tragic purity of Orfeo and Alceste recovers in Paride ed Elena something of the baroque sensuousness of Gluck's earlier Italian operas, perhaps in response to the Ovid-based text, and these arias were for me the real revelation of the disc; indeed, they make me wonder whether the opera doesn't deserve a complete recording, preferably with Dame Janet as Paris, in spite of the dramatic weaknesses that have kept it off the stage. In the absence of a complete version, though, it is good to have these four arias so exquisitely sung, even if it means that "Spiagge amate" has to be given an ending Gluck never wrote in order to round it off satisfactorily. (In the opera Paris is interrupted by a Spartan messenger before he can finish.) There is no such excuse, though, for presenting Orpheus' rapt vision of the Elysian Fields in a version that is true neither to Gluck's music (in either the Vienna or the Paris versions) nor to Calzabigi's text. If Dame Janet prefers to sing the Paris version as rewritten by Berlioz for Pauline Viardot, she has every right to, of course; great singers' whims deserve respect. But why do it in the late -nineteenth-century retranslation into Italian, particularly since she has already shown how good her French is? And although I entirely concur with her use of the extended Paris ending of "Che faro?" even in an Italian performance (it is an improvement), I do wish she had pronounced the heroine's name correctly, and not with a nasty German "Oy" sound for its first syllable.

Raymond Leppard and the English Chamber Orchestra accompany as sympathetically as one would expect, though once or twice (notably in Armida's and Alcestis' great scenas) I felt that the music was being taken too slowly in the determination to wring every drop of expression out of it.

The voice's natural tessitura is perhaps a shade too low for these roles, and occasion ally this results in a slight edge to the timbre, but how many mezzos are there around who can cope equally well with the tragic grandeur of Armida's farewell and the pert flirtatiousness of Balkis or Amine? Truly a remarkable singer, and I only hope that this record will, instead of pre-empting the market, encourage some company to cast her in a complete recording of one of Gluck's operas.

-J.N.

HANDEL: Organ Concertos (16). Lionel Rogg, organ of the Abbey St. Michel de Gaillac; Toulouse Chamber Orchestra, Georges Armand, cond. [Eric Macleod, prod.] CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CSO2 2115 (Nos. 1-6, 13, 14) and 2116 (Nos. 7-12, 15, 16), $13.96 each two-disc set (SQ-encoded, manual sequence).

After a long dry spell for the Handel organ concertos, what a sudden wealth of choice! Juit as the long-standard Biggs/Boult recordings of 1958-59 were being given new life by Columbia as D3M 33716, Telefunken released its purist version-authentic period instruments throughout-of Opp. 4 and 7 by Herbert Tachezi and the Vienna Concentus Musicus under Nikolaus Harnoncourt (36.35282, March 1976). And now, as I listen to the new Rogg/Armand set (released domestically by Connoisseur Society even before Pattie Marconi's French issue), two highly promising sets of all sixteen concertos await U.S. issue: Daniel Chorzempa with Jaap Schroder con ducting for Philips. and George Malcolm (on organ and harpsichord) with Neville Marriner conducting for Argo.

While a detailed comparative survey is not yet possible, it's already evident that there are two basic approaches. One uses an actual period or replica organ and period or replica orchestral instruments-mostly oboes and strings, occasionally also horns all tuned about a half tone lower than to day's 440 A to approximate practice of the baroque period (although there was a considerable range of variation in those non-standardized days). In this group are the Telefunken recordings, the recently with drawn 1967 Muller/Wenzinger Archly set, and the forthcoming Philips.

The other approach admits the use of modern instruments (except, of course, for the solo organ and the continuo harpsichord) and the present-day pitch standard, while still insisting on a greater or lesser degree of baroque -era stylistic authenticity in the use of improvised passages, ornamentatains. etc. The new Rugg set falls into this group. where it strikes me as likely to be come the must admirably satisfactory--and stimulating--of all. (The Argo set will not compete directly. since it presents two of the concertos in harpsichord versions and uses three different British organs in the others.) The present release has the economic convenience of allowing purchase of one album at a time: and also includes Peter Eliot Stone's valuably informative notes on the works' complicated origins, metamorphoses. and plagiarisms (of others' as well as I lamlel's own works). All that's lacking are building/restoration dates and stop specifications of the Abbey organ itself.

Handel specialists may argue about the appropriateness of Rogg's choice of organ, editorial details. etc. What delights me is his ability to make the best of both worlds.

Despite--or because of--the absence of period orchestral instruments (and of the sometimes niggling eccentricities of their intonation and timbre coloring), the over all sonorities and the authoritatively idiomatic readings not only are immediately entrancing, but seem to be superbly evocative of the spirit of baroque -era ideals. Above all, the Swiss master excels here by the aptness and seeming spontaneity of the many passages left open for the soloist's own improvisation. Without score-checking, it is well-nigh impossible to decide just where Rogg takes over from Handel and just where Handel returns.

Yet even the infectious relish and arresting authority of these performances hardly could achieve the spellbinding effect they do if they had not been so magically re corded in the reverberant ambience of the Abbey of St. Michel de Gaillac-one thrillingly impressive in stereo only, even more gloriously expansive in quadriphonic play back. R.D.D.

HAYDN: Piano Works. For an essay review, see page 106.

HAYDN: Trios for Violin, Cello, and Piano: in A flat, H. XV:14; in G, H. XV:15. Beaux Arts Trio. PHILIPS 9500 034, $7.98.

I wish musicologists did not find it necessary to apologize on behalf of Haydn's piano trios for their not being string quartets.

Apart from the fact that the medium itself is essentially a less contrapuntal one, there is nothing in these two pieces, both written about 1790 when Haydn was at the very height of his maturity, to suggest that he was writing down for young lady amateurs, as the writer of the liner note seems to imply.

In No. 14 the unusual key of A flat certainly seems to have brought out a particular vein of gentle lyricism in him, but there is nothing in the least insipid about the quality of his invention, with its adventurous exploration of mediant key relation ships, both within the first movement itself and in the relation of the E major (F flat) Adagio to the outer movements. This piece was apparently published as a sonata "for harpsichord or pianoforte with violin and violoncello accompaniment," but, although the piano certainly takes the lead at the start, the violin comes fully and indispensably into its own in the songlike slow movement, taken here at a perfectly poised tempo.

The other trio in this record is brisker.

sharper in character, at least in its outer movements, with a witty rhythmic surprise reserved for its very last measure. Since it was first published as a trio for piano, flute, and cello, I have been trying to imagine how it would sound with a flute in place of the violin but really can't think it would work as well: There is a rhythmic incisive ness about Isidore Cohen's playing that I can't imagine the best of flutists matching.

Bernard Greenhouse has to show his artistry largely through discretion, since even in these late works the cellist has very little to do beyond pointing up the bass line; it says much for him that he manages to per form so unglamorous a task with unfailing vitality. But the central role in both these pieces is the piano's, and Menahem Pressler assumes it with completely persuasive leadership, always ready to let his partners make their contribution and to relish his dialogue with them.

The recorded sound is beautifully balanced, and the surfaces, on my copy, impeccable. J.N.

MAHLER: Das Lied von der Erde. Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; James King, tenor; Concertgebouw Orchestra, Bernard Haitink, cond. PHILIPS 6500 831, $7.98. Tape: APO 7300 362, $7.95.

Among today's great virtuoso ensembles, there are several with a special Mahler identification, but only in Amsterdam, I feel, do they make precisely the sound, in quite the cultivated way, with quite the lightness and crispness and translucency, to realize all the pictorial poignancy of the instrumental canvas of this great song sym phony. If the Concertgebouw's third re corded Das Lied does not entirely duplicate the splendors of its first, Van Beinum's magisterial mono account (last available domestically on World Series PHC 2-011, rechanneled), it is a magnificent achievement in its own right.

Van Beinum's first oboe and trumpet remain unequaled, and his horns managed the off -beat triplets of "Von der Jugend" (bars 66-68 et seq.) with a rustic yet aristocratic quality lost under Haitink-though this may have something to do with the closer, perhaps overdose, miking of the new Philips. Yet there are ample compensations. Listen, in the first song ("Das Trink lied vom Jammer der Erde"), to the stretch from Nos. 25 to 34: The élan and smooth ness of the flutes' flutter-tonguing and staccato eighth notes, the violins' pure yet decisive attacks are among the many highlights.

The clarinets do marvelous things in "Der Abschied" (e.g., No. 4 and, later, beginning five before No. 55). "Der Einsame im Herbst" is filled with a high level of limpid first -desk artistry, as is the closing page of "Von der Schonheit."

In the best chamber-music tradition (and many people have commented on the intimate scoring of Das Lied), it is obvious that the Amsterdam players listen to each other and are welded into a coherent and compatible ensemble personality. And Haitink's interpretive contribution is noteworthy. The first song has a forward impetus and gnarled tension I haven't heard since the 1936 Vienna concert performance under Walter (Seraphim 60191).

Haitink brings a broadly reflective quality to the second song ("Der Einsame im Herbst"), without disrupting its ebb and flow of tension. If there are no startling in sights brought to the remaining tenor songs, neither are there interpretive improprieties.

Haitink's "Abschied" has a grand over-all stride to it, as well as plenty of breathing space for the ineffable stillness and desolation of the music to achieve its crushing yet uplifting effect.

Many of us have long awaited Janet Baker's participation in a Das Lied recording. Judging from earlier performances that have circulated in the underground (including a late -Sixties broadcast with Szell), some may feel that the wait was too long, given the current state of her vocal equipment. It is hard to deny that floating a softer tone even in the upper middle register can nowadays be a rather perilous undertaking for her. (Note the wobbly e sustained on "O sieh" between Nos. 4 and 5 of "Abschied.") But all executant problems aside, she brings to these songs a level of comprehension and skill that is almost unfailingly eloquent. In "Der Einsame im Herbst" she sounds utterly remote at "ein halter Wind"; she is all warmth and passion at "Ich weine viel in meinen Einsamkeiten." In "Von der Schonheit" her reading of the word "Sehnsucht" (No. 18) calls to mind the shadings of Ferrier (Richmond R 23182). In "Abschied" there is all the white tone-lessness called for at "Erstieg vom Pferd" after the interlude, yet "Ich suche Ruhe" is a profoundly felt cry of anguish. In the final "ewigs," marked pp and ppp, Dame Janet's tone virtually melts away into the infinite.

A performance of this caliber undoubtedly deserves a tenor more distinguished than James King, though he does little to really offend. The voice and manner are neither as ringingly heroic as some would like nor as malevolent as I would (cf. Patzak on the Ferrier/Walter). But King sings cleanly and even pays a little attention to a few more word meanings since his last try, with Fischer-Dieskau and Bernstein (Lon don OS 26005), a performance otherwise worthy of serious competitive consideration.

Philips' new Das Lied clearly belongs in the select company of classic recordings of this intoxicating masterpiece. Among avail able modern recordings with female soloist, it goes straight to the head of the class.

- A.G.

MASSENET: Esclarmonde. Esclarmonde Parseis Roland Eneas A Byzantine Herald Bishop of Blois A Saracen Envoy Phorcas Cleomer Joan Sutherland (s) Huguette Tourangeau (ms) Giacomo Aragall (1) Ryland Davies (t) Graham Clark (t) Louis () wilco (b) Ian Caley (b) Clifford Grant (be) Robert Lloyd (be) Finchley Children's Music Group, John Alldis Choir, National Philharmonic Orchestra, Richard Bonynge, cond. [Michael Woolcock, prod.] LONDON OSA 13118, $20.94 (three discs, automatic sequence). Tape: Ov OSA5 13118, $23.85.

Esclarmonde is one of Massenet's large-scaled operas, written for the youthful Sybil Sanderson and premiered at the 1889 Paris Exposition, where it was a huge success and ran all summer; the public adoring the combination of eroticism and lavish Byzantine settings. After a few years, though, it sank from sight, and the 1974 San Francisco Opera revival, transferred in 1976 to the Metropolitan--which involved most of this cast-was the first in modern memory.

There has been an amount of received opinion that opines that Massenet could write small-scaled works but not grandiose ones. This opinion will doubtless still be heard, but Esclarmonde is no dead dodo of an opera, even though the plot is better off comprehended through Esclarmonde's veil.

It is a gloss of a chivalric romance (and as such fits into the vogue for grand opera that characterizes French opera through the centuries) and involves a mythic kingdom, a princess with magic powers, a Hero Lover, a magic island, burning cities, a wicked bishop, exorcism, a tournament and lots of musicalized sex. It has a happy ending.

At the time of its composition Massenet was accused of writing in Esclarmonde like Wagner and a dozen other composers. Massenet, however, was too accomplished a composer to indulge in imitation, although if you listen closely enough you may hear some echoes (less of Wagner, except in the chromaticism and the use of an outsized orchestra, than of Berlioz). The one opera, strangely, that Esclarmonde most strongly suggests to me was not written until after Massenet was dead: Richard Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten. This is because of the fairy-tale aspect and wide range of scenes in both works, and because the musical motif of magic powers that Massenet uses in Esclarmonde is very similar, in rhythmic shape, pitches, and, primarily, orchestration, to the Keikobad motif.

George Bernard Shaw scoffed at Massenet's use of motifs as thoroughly un-Wagnerian, and he was largely right. Massenet uses them in a rather simplistic way, as ostinato accompaniment patterns, similar to their use in Meyerbeer or in later (and today unknown) French opera composers such as Ernest Reyer. It can be argued that Strauss harked back to this method in his manipulation of motifs in Frau.

But what is central to Esclarmonde is not the repetition of motifs or the grandiosity or the ever-plush harmonies, but the contribution that Massenet made and that no one else can duplicate: the "phrase Massenetique." This is the creation of an undulating musical line which seems to unwind for ever-a line which demands that the singers observe (with an innate freedom) minute instructions as to phrasing, breathing, and dynamics. When correctly performed, by both orchestra and singer, the music allows the text to become musical declamation of extreme expressivity. This opera, in part because of the vocal abilities of Sybil Sanderson, abounds in such music-listen to Sutherland's ariosos at the beginning and end of Side 5.

What is distinctive about this recording apart from the presentation of an opera worthy of being reconsidered-is the evidence that Sutherland and Bonynge have done a lot of hard work. Bonynge, probably because of his conducting of ballet scores, has learned how to phrase with a flexibility that enlivens Massenet's writing, and Sutherland follows his lead. Her voice is, frankly, not the ideal one could imagine in the role, for it lacks the sensuous languor it should have, but she is properly ardent and who else could get up with such ease to the D's, F's, and even a G in alt? Her enunciation is dramatically improved, and her French is leagues better than Giacomo Aragall's.

Aragall is a better Roland on records than he was on-stage, but the voice is rather stiffly produced and he really cannot--or does not want to-sing softly. The rest of the cast is quite good, especially Louis Quilico's Bishop and Huguette Tourangeau's Parseis. Her duets with Ryland Davies are properly classically cool, to be set against the ardor of the principals.

The score is, if never deep, nonetheless full of varieties of beguiling music (in keeping with the magical elements) in Massenet's best vein. This music may be diffused on spectacle rather than concentrated, as in Manon and Werther, on character, but Massenet here was not interested in character portrayal. As such, Esclarmonde is entirely typical of a type of spectacle opera we only rarely encounter today.

Bonynge makes several cuts in the score, none extensive. The recording has presence and definition as to voice and solo instruments, but the big climaxes and the choral moments are muddy and diffused.

-P.J.S.

MASSENET: Thais. Thais Athanael Nicias Palemon Crobyle Myrtale Albine La Charmeuse A Servant Beverly Sills (s) Sherrill Ines (b) Nicola' Gedda (t) Richard Van Allan (bs) Ann-Mane Connors (s) Ann Murray (ms) Patricia Kern (ms) Norma Burrowes (s) Brian Ethridge (b) John Alidis Choir, New Philharmonia Orches tra, Lorin Maazel, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.] ANGEL SCLX 3832, $21.98 (three SQ - encoded discs, automatic sequence). Tape: 4X3S 3832, $23.98.

Comparison: Motto, Bacquier, Carreras, Rudel RCA ARL 3-0842 After Anna Moffo's Thais, Beverly Sills's comes as a distinct relief. Whereas Moffo in the RCA set is scarcely able to sustain her place in the score, Sills, as always thoroughly professional, sings with the basic competence that is surely a minimum requirement for any recording.

Always at her very best--or so it seems to me--in French opera, where beauty of tone and emotional spontaneity are less important than nuance and dramatic liveliness, Sills phrases a lot of this music with real psychological insight, especially in those places where pathos or lighthearted voluptuousness is called for. In the exchange with Nicias that follows upon her entrance in Act I, she sounds positively bemused by sensuality. She makes something vivid, too, out of the middle section of the Mirror Aria, where the courtesan, grown suddenly pensive, expresses her fears about aging. Her characterization of the heroine at the oasis-bleeding, exhausted, and contrite--is sensitive.

That all of this doesn't add up to a great deal more is due, I think, to the quality of Sills's vocal production, which, as usual these days, is un-pleasingly fluttery. Unlike Moffo, she has all the notes. The trouble is she doesn't have them very satisfyingly.

Quite apart from the moments of aural pain (what, I wonder, can have possessed her to try for the high alternative-a D in alt-to the B flat at the conclusion of the Mirror Aria?), the voice in general sounds tired, unsteady, and shallow in tone. "L'amour est une verturare," neither high in tessitura nor excessively demanding in technique, gets lost in the all-pervasive tremolo that now seems basic to her vocal production.

What a pity that this recording could not have been made ten or even fifteen years ago, when Sills's voice, un-fatigued by Roberto Devereux, Maria Stuarda, and the like, was still charming to listen to.

The same, as far as I'm concerned, is true of the other two principals. Certainly the Sherrill Milnes I first heard in the mid-Sixties possessed an instrument of extraordinary beauty and magnificence, which overemphasis and a too eager desire to knock the audience cold reduced fairly quickly to the merely loud and strong. As Athanael, Manes is tireless, aggressive, and un-fascinating. Though his French, like everyone's in this well-prepared cast, is good, he doesn't really know how to make language help him shape the music expressively and he soon becomes monotonous.

Moreover, like Sills, he now has an uncontrollable tremolo, though it is as yet mostly confined to anything below forte.

In full voice Milnes is often, of course, awesome, but there is no trace of elegance or smoothness in his work, largely because the tone remains unfocused and woolly. In his anxiety to impress, he has sacrificed too much in the way of vocal control. Now, I notice, he is scanting short, unstressed notes in his seeming eagerness to get to the big, long, important ones. Gabriel Bacquier in the RCA set, while clearly beyond his vo cal prime, is an Athanael of much greater persuasiveness, a vocal actor with a highly developed sense of verbal inflection and tonal coloration, a fanatic whom we can empathize with and in the end feel pity for.

And for all his discomfort in climactic pas sages, he is on the whole a far smoother singer than Milnes.

By comparison with Jose Carreras, RCA's Nicias, Nicolai Gedda is a model of dramatic responsiveness: Carreras does virtually nothing but sing beautifully, whereas Gedda, intelligent artist that he is, shows unflagging awareness of every nuance in the character's relations with Thais. Unfortunately Gedda's performance doesn't really work. The voice is now too inelastic and dry to suggest-as Carreras, for all his dramatic blankness, does-the careless self-indulgence of youth. Gedda sounds too neurotic and calculating, a furtive nail -biter rather than a heedless young voluptuary, Strauss's Herod rather than Massenet's Nicias.

The remainder of the cast, with one exception, is more than satisfactory, and Norma Burrowes, who sings the tiny role of La Charmeuse in the lengthy ballet sequence that Massenet added to the score after the premiere, is excellent. Technically fluent-her staccatos, runs, and trills are beautifully clean-she is also graceful and expressive. The exception to the general, high standard is Richard Van Allan, whose Palemon, the leader of the group of Ceno bite monks to which Athanael belongs, is something of a trial, his tone being mushy and unpleasant.

Lorin Maazel conducts with assurance, if not complete conviction. I find his tempos too slow in many of the big lyrical scenes, particularly the opera's finale, where the mood of near-hysterical ecstasy eludes him. In addition to conducting, Maazel plays the solo violin in the famous "Meditation" that Massenet puts to such full use in this opera. Maazel's fiddling is certainly proficient, though not quite accurate enough in intonation. Having recently heard the concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony, Jacob Krachmalnick, play this music for the San Francisco Opera's Thai's (starring Sills and Milnes) with sweet, round tone, beautiful phrasing, and perfect intonation, I find myself less enthusiastic about Maazel's versatility than I might otherwise be. Where Maazel excels is the ballet music, whose brilliance and exoticism he projects very persuasively.

The recording is clear. I could have done without the wind machine in the second scene of Act III, even though the libretto tells us that "in the distance the simoon wind is howling." Fortunately we are spared the other atmospheric effects called for: "Jackals yelp and lions roar from the depths of the forest." Notes, libretto, translation.

-D.S.H.

MESSIAEN: Quatuor pour la fin du temps. Tashi (Richard Stoltzman, clarinet; Ida Kava fian, violin; Fred Sherry, cello; Peter Serkin, piano). [Max Wilcox and Peter Serkin, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1567, $6.98.

Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time, composed within and inspired by the bleak surroundings of a German stalag where the composer was imprisoned in 1940, has be come one of the staples of the modern chamber repertoire. I have even heard the final movement, which is for violin and piano alone, performed as an encore! Beyond the undeniable beauty of the Quatuor, Mes siaen's music in general has a marked non-Western orientation definitely in tune with modern sensibilities, and pianist Peter Serkin and the Tashi group supremely represent these sensibilities.

Scored for the violin, cello, clarinet, and piano available to the composer in the stalag, Messiaen's Quatuor demands both ex pert ensemble work and exceptional solo ability. Three of the eight movements high light a single instrument-in the third the clarinet plays alone, while the fifth and eighth offer, respectively, a cello and a violin duo with the piano. Tashi comes through beautifully in both areas.

While there has never been a bad recording of the Quatuor, Tashi perhaps comes the closest of any group to communicating the often impassioned emotional depths of the work as well as its technical brilliance.

In the all-unison sixth movement, for in stance, not only do the players provide a razor sharp, intensely vigorous performance of the rapidly paced rhythmic and inter-valid convolutions, but they also, at certain moments, produce a rather uncanny resonance apparently at least partially created by some ingenious pedaling from pianist Serkin. Clarinetist Richard Stoltzman, weaving in and out in perfect sync with Messiaen's cyclical waves of musical feeling, from the long thematic meditations to the birdcall intricacies, provides, in the third movement, the disc's solo highlight.

The recorded sound could be brighter and cleaner, especially the piano; but basically it complements Tashi's efforts quite well. R.S.B.

RACHMANINOFF: The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29; Symphonic Dances, Op. 45. London Symphony Orchestra, Andre Previn, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.] ANGEL S 37158, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

RACNMANINOFF: The Bells, Op. 35; Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14. Sheila Armstrong, soprano', Robert Tear, tenors; John Shirley-Quirk, bass -baritones; London Symphony Chorus and Orchestra, Andre Previn, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.] ANGEL S 37169, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc). Previn's EMI Rachmaninoff series continues in its superlative vein.

Though mysteriously neglected by con cert programmers, The Isle of the Dead must surely be one of the half -dozen or so finest tone poems ever written. Shrouded in a kind of subterranean despair, like Bocklin's painting that inspired it, the piece also maintains a long -spanned, singing line that, if properly shaped by the conductor, conveys deep and noble resignation. The com poser's own reading with the Philadelphia Orchestra (available in RCA ARM 3-0295) suffers the dual misfortune of ill-advised cuts and antiquated sonics, but it still stands as an object lesson of tautness and gorgeous playing. Note how the passage be ginning in the middle of p. 38 of the IMC miniature score is sustained as an unbroken lyric line for some sixty measures. Among complete stereo recordings, both Reiner (RCA Gold Seal AGL 1-1523) and Svetlanov (Melodiya/Angel SR 40019 or SRBL 4121) distend and sectionalize that episode. The former is further impeded by opaque sonics, the latter by raucous playing.

Previn's Isle, if not quite as grimly linear as the composer's, is certainly free of gratuitous misshaping and exhibits control over the music's time span and cantabile expression, all with lucidity and sensitivity. EMI's team has unscrambled the somewhat thick orchestral texture in a pleasing way that doesn't sacrifice warmth and atmosphere.

This is certainly the practical recommendation for the work, though it would be challenged by a general commercial issue of the Horenstein/Royal Philharmonic version for Reader's Digest.

There has been no shortage of good recordings of the Symphonic Dances, but Previn imbues the score with a startlingly fresh poetic glow and emotional commitment. Adopting a free, rubato-laden frame work, he glides from the first movement's livelier theme group into the lyrical counter-theme (first introduced on saxophone) in a melting way that tingles with sensuous ness. Previn's lilting hesitation in the second movement (Rachmaninoff originally called it "Twilight"), with the delicacy of the playing and the color and detail of the recording, reveals freshly the pining nostalgia and bitter-sweetness of that music.

The finale is its usual diabolical self, but Previn's accenting and timing of Luftpausen add an immeasurable quality of passionate yearning.

Taken by itself, Previn's Bells is equally fine, though it doesn't run away with the field. There is still much to admire in the Ormandy (RCA ARL 1-0193) and Kondrashin (Melodiya /Angel SR 40114) recordings, which I discussed in June 1974. The weak spot of the new issue is John Shirley -Quirk, whose solo in the last movement (the tolling funeral bells) suffers from general rawness and breathing problems. Tenor Robert Tear is in his best form in the opening movement, while soprano Sheila Armstrong is adequate, perhaps a bit matronly, in the second (wedding bells) movement. RCA's soloists are the most even and assured technically, Melodiya/Angel's the most radiant in their emotional fervor. The London Sym phony Chorus is in splendid form (singing in Russian; Ormandy used the Copeland English translation). Previn bends with the score's lyricism somewhat more freely than Ormandy, though neither possesses the jagged wildness of the Soviet performance.

Unquestionably, the two Western recordings reveal more of what is going on in the score, Angel surpassing RCA principally on occasional bass -line details (tubas and bass clarinets).

Previn's Vocalise is gentler than Ormandy's, more broadly arched than Stokowski's ( Columbia MS 7081 and Desmar DSM 1007, both paired with the Third Sym phony). It's a shade lighter than Johanos' '(the filler to his Symphonic Dances. Turn about TV -S 34145). I can't say which is "best": any maestro not made of stone, and whose string section isn't playing on sand paper, can't help but make the piece heart warming. A.C.

SCHUMANN: Sonata for Piano, in F minor, Op 14 (Concerto Without Orchestra).

SCRIABIN: Sonata for Piano, No. 5, in F sharp, Op. 53. Vladimir Horowitz, piano [John Pfeifer, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1 1766, $6.98. Tape: "we ARK 1-1766, $7.95. 4). ARS 1-1766, $7.95.

RCA calls this "The Horowitz Concerts, 1975/1976" but is purposely vague about specifics. From the spacious auditorium ambience, wonderfully suggestive of the pianist's breathtaking dynamic range, it seems most likely that these performances are composites from a number of live concerts. What really matters. however, is not how these recordings were made, but that they were made, that they sound marvelously true, and that the playing is -even for Horowitz -quite exceptional.

Though Horowitz has three times re corded the slow movement of Schumann's Concerto Without Orchestra--the introspective set of variations on a theme by Clara Wieck--he has been long in coming to the whole F minor Sonata. Now he feels, quite rightly, that the variations make a much stronger impression as part of the larger work and vows to play only the complete sonata. With his pianistic wizardry and marvelous sense of color, he makes the thickly scored, disjunct writing spring to life in a way that few have managed.

This is not to say that his is the only way to play this music. The excellent Engel performance (in Telefunken 46.35039), for ex ample, is strong and full of structural integrity--German music --making in the best sense and perfectly idiomatic Schumann.

Horowitz offers a more agile, varicolored sonority, infinitely more exaggeration and electricity, and, in the end, greater tender ness and complex poetry. Engel, incidentally, plays the three-movement version but adds both of the omitted scherzos as an appendix; like most of his colleagues on record, Horowitz uses the text that restores one of the scherzos.

Horowitz has always been the Scriabin pianist par excellence, and his reading of the Fifth Sonata deserves to take its place alongside his versions of the Third, Ninth (two very different accounts, both incredible), and Tenth and Vers la flamme. He gives the sonata a brilliant, febrile, and mystical account, with full value to all the cross-rhythms and neo-jazz zaniness. I have not heard the new Ashkenazy recording [Royal S. Brown turns thumbs down on the Fifth Sonata in his review this month. -Ed.], but Horowitz safely outdistances all the others. H.G.

Scriabin: Sonatas for Piano: No. 3, in F sharp minor, Op. 23; No. 4, in F sharp, Op. 30; No. 5, in F sharp, Op. 53; No. 9, in F, Op. 68 (Black Mass). Vladimir Ashkenazy, piano. [Ray Minshull, prod.] LONDON CS 6920, $6.98. Comparisons: Laredo (No. 5) Conn. Soc. CS 2032 Kuerti (No. 4) Mon. MCS 2134 Horowitz (No. 9) Col. M2S 728

This disc captures Scriabin at the end of his Romantic period, moves through both the sonatas of the brief but marvelously rich transitional period, and concludes in the icy yet multicolored mysticism of the final visions. I have yet to hear a pianist equally at home in all of these phases (Ruth Laredo comes closest), and that includes Vladimir Ashkenazy. He plays both of the transitional sonatas (Nos. 4 and 5) in such a choppy, superficial, and un-sonorous manner that the music seems gasping for air most of the time. And while No. 9 fares better, Ashkenazy performs it too much as a virtuoso piece, ignoring contrasts (and many dynamic indications) and showing little interest in the otherworldly, visionary quality of certain passages. The work does not necessarily call for Horowitz's steely coldness, although his approach works beautifully, but it needs a lighter, more ethereal touch than Ashkenazy brings to it.

The Third Sonata, however, receives one of its best recorded performances. The dramatic, often patetico energy, the quiet fadeouts into passages of a sweet and yet sad tenderness, the rich, chordal dynamism-all of these elements of Scriabin's elusive first style are expressed in Ashkenazy's sensitive interpretation. To be sure, there is still some breathlessness in the chordal passages, some ponderousness in the quieter sections. But the pianist obviously moves in the same orbit with the Scriabin of the Third Sonata, and the result is exciting and often deeply moving (though the surfaces of my copy were terribly messy).

As for the other sonatas, rely on Kuerti for the Fourth, Laredo for the Fifth (her Ninth on the same disc is also admirable), and Horowitz for an unearthly, chilling Ninth.

R.S.B.

TCHAIKOVSKY: The Nutcracker, Op. 71. St. Bavo Cathedral Boys' Choir ( Haarlem), Concertgebouw Orchestra, Antal Dorati, cond. PHILIPS 6747 257, $15.96 (two discs, manual sequence).

Antal Dorati first came to prominence out side Central Europe as a ballet conductor. From 1934 to 1937 he was with Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, from 1938 to 1941 with Original Ballet Russe, and from 1941 to 1945 with Ballet Theater (now American Ballet Theater), for which company he was also music director. During these years he devised several distinguished ballet scores to pre-existent music, among them Michel Fokine's Bluebeard to Offenbach and David Lichine's still popular Graduation Ball to Johann Strauss.

This information is worth imparting, I feel, for two reasons. First, the notes on Dorati included in this album are sketchy and inaccurate-they credit him with having been for five years the Director (sic) of the National Ballet, New York, a company that never existed outside the imagination of Philips' copy writer. Second, Dorati's practical experience with music for dancing needs emphasizing, because that doubtless is the explanation for his faultless grasp of Tchaikovsky's theatrical intentions.

Though I have a long-standing affection for the wonderfully graceful, though slightly cut, Nutcracker by Ansermet and the Suisse Romande (London CSA 2203) and for the more recent Bonynge performance (London CSA 2239), Dorati seems to me to realize the work more fully, all in all, than anyone else on records. I suppose it's a bit late in the day to commend Tchaikovsky, but I find it hard to refrain from doing so in the case of The Nutcracker, since what is most frequently heard, the Op. 71a Suite, contains the weakest part of the score-skillfully made music, and with brilliant strokes of orchestration, but lacking the individuality and the radiance that warm the many great pages of the work as a whole: the Act I scene in which the Christmas tree grows enormous; the finale of this same act, with its transformation of the Nutcracker into a handsome prince and the journey he and ^,lara take through a snowy forest; the prelude to Act II and the arrival of the travelers in Konfiturenburg; the adagio movement of the climactic pas de deux. Those who know only the suite can have little conception of Tchaikovsky's genius as a ballet composer, of the grandeur he could achieve, and of the depth of feeling he could reveal. All of this Dorati under stands and transmits.

His previous recordings of the complete ballet, with the Minneapolis Symphony and the London Symphony, were excellent.

The new one is even better. The advance in recording technique and Philips' silent surfaces are distinct improvements, and so decidedly is the warmth and mellowness of the Concertgebouw.

The notes, as I've implied, could be improved. Apart from their inadequacy on Dorati, they offer only three un-illuminating paragraphs on the ballet and a listing of numbers far too un-detailed to be of any real use.

- D.S.H.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Symphony No. 5, in E minor, Op. 64. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond. [Michel Glotz, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 699, $7.98. Tape: MI 3300 699, $7.98.

Readers of my July 1975 survey of Tchaikovsky symphony recordings will re call that neither Herbert von Karajan nor the Fifth Symphony drew much praise.

With this extraordinary new record, the most exciting performance of the Fifth I have heard since the (quite different) Koussevitzky/Boston Symphony performances of four decades ago, I must eat at least some of those critical words.

Karajan's way with Tchaikovsky has not in the past been an especially happy one. His earlier DG Fifth (139 018, 1968) was matter-of-fact in approach, distant in ambience. The subsequent Angel recording (S 36885, 1972) went to the other extreme: miked rather closely, interpretively literal and tense, even aggressive. The new recording is totally different, beginning with the engineering, which is more forward than the earlier DG but not as close as the Angel.

This rather matches the new interpretation, in which the drama of the symphony is heightened, but without the crudity of the Angel version.

The intensified rhetoric is never allowed to break continuity; despite the frequently slow tempos and liberal use of superbly calculated pauses, Karajan consistently maintains the long musical line. In the Andante especially he builds impressively from the opening horn solo, following it with increasing variety of development and building climaxes of exceptional power. He foes not gloss over what I would consider the score's basic defects. Where Tchaikovsky's climaxes are feverish and overblown, Karajan follows explicitly, neither underplaying nor exaggerating. He responds throughout with honesty, expressive commitment, and superb musicality, including amazingly precise observance of detailed dynamic and tempo markings that yet never leaves the impression of pedantically dotting i's and crossing t's.

Obviously a major glory of this record is the sheer sound of the Berlin Philharmonic, whose tonal balance and blend at all tem pos and dynamic levels are above criticism.

Moreover, that sound is captured here with a realism and sensuous beauty that put little between the original and the listener.

Indeed, were I not put off by the Fifth Sym phony's basic banality of conception, I would place this recording alongside Furtwangler's great Pathetique in the discographic pantheon. For that legion of listeners with no such misgivings, this should be an indispensable recording for years to come.

P.H.

TIPPETT: Symphony No. 1; Suite for the Birthday of Prince Charles. London Symphony Orchestra, Colin Davis, cond. PHILIPS 9500 107, $7.98.

A welcome side effect of Tippett's belated recognition as one of the major figures on the English musical scene has been the fresh attention it has brought to some of his earlier, half-forgotten works. Not that any of them are all that early, since Tippett, a slow and self-questioning developer, rejected everything he had written before his mid -thirties; as Bayan Northcott reminds us in a notably well-informed liner note, he had turned forty when this symphony was completed in 1945.

It is an eager, strenuous, attractive work, which nevertheless poses certain problems to immediate comprehension that are found neither in predecessors like the Concerto for Double String Orchestra nor in the more "liberated" works that followed the opera The Midsummer Marriage, works in which Tippett began to discard the formal apparatus of musical dialectic in favor of a more instinctive, gestural style. When the First Symphony was first given in England, critics were quick to point out the difficulty of reconciling a highly contrapuntal idiom with the structural demands of a relatively conventional four -movement symphonic form, and to some extent this is still a stumbling block. In the first movement the contrapuntal texture, combined with Tippett's characteristic loose-limbed phrase lengths, distracts the ear from the large-scale thematic and tonal argument, and even in the slow movement, an extended passacaglia, the proliferation of detail tends to impede the momentum of what should, after all, be the most inexorable of forms.

So much, though, only by way of explaining why this symphony has taken so long to come into its own-something that Colin Davis' splendid reading of it will surely achieve. Under his committed guidance the sprung rhythms spring as they should, yet there is no loss of thrust or over all direction, even in the most densely polyphonic passages. The fleet rhythms of the scherzo (the most Stravinskian movement of the four) are beautifully precise, and the powerful double fugue in the finale leads with irresistible energy to the strange but completely convincing ending: The dance spins away and dissolves, leaving only the irregular pounding of a low E. the dominant, as if the source of so much energy were still unexhausted.

It was an imaginative gesture on the part of the BBC to commission a work from Tippett to celebrate the birth of an heir to the British throne three years later; even then he was not an obvious composer of occasional music. Lighter in mood than the sym phony, the suite is still far from insubstantial. Its five movements all make use of traditional tunes-the Scottish hymn -tune "Crimond," a plangent French lullaby, an Irish reel, an English carol, and many more in the final quodlibet-but they are used with an energy and imagination that take them far beyond the scope of mere arrangements. The recorded sound is well and naturally balanced, if a little too reverberant for all the polyphonic detail to tell.

-J.N.

-------------------

VERDI: Macbeth.

Lady Macbeth Gentlewoman Second Apparition Third Apparition Macduff Malcolm Macbeth First Apparition Banquo Doctor Servant to Macbeth Murderer Herald Shirley Verrett (ms) Stefanie MalagO (ms) Maria Fausta (s) Massimo Bodoloth (boy s) Placido Domingo (1) Antonio Savastano (t) Piero Cappuccilli (b) Alfredo Giacomotti (b) NicolaGhiaurov (bs) Carlo Zardo (be) Giovanni Foam (bs) Alfredo Menotti (be) Sergio Fontana (bs)

---------------------

La Scala Chorus and Orchestra, Claudio Ab bado, cond. [Rainer Brock, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 062, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Tape: fiFe 3371 022, $23.94.

Comparisons: Rysanek, Warren, Leinsdort Vlctr. VICS 6121 Nilsson, Taddel, Schippers Lon. OSA 1380 Souliotis, Fischer-Oleskau, Garden' Lon. OSA 13102

---------------

Of all the early Verdi operas, Macbeth has been the most frequently recorded--and with justice, for despite its obvious crudities and banalities, it contains passages (even whole scenes, arias, finales) of unforgettable musico-dramatic power and is one of those pieces that, in a reasonably successful performance, draws the audience into an almost tangible psychological atmosphere entirely its own.

DG's is the fourth complete recording, all in stereo. (There was also an abridged German--language performance featuring Elisabeth H iingen and Matthieu Ahlersmeyer, released domestically on Urania.) Like the other three, it is basically the revised (1885) edition of the score. It offers the complete ballet music in the apparition scene (as does the Gardelli/London version, but not the others) and includes from the early (1847) edition the death scene for Macbeth (as does the Leinsdorf/Victrola version). Like the Leinsdorf/Victrola, it is based on a stage production (La Scala 1975 in this case, Metropolitan 1959 in Leinsdorf's).

I find the new performance a solid, generally recommendable one. Yet it seems lacking in profile, and for this reason I find little impulse to return to it, as I sometimes do to the Leinsdorf and Schippers performances. (Gardelli's has profile, all right, but one that is marked by the ragged scars left by two of the more inappropriate casting choices in the combined histories of wax, shellac, and vinyl: the Macbeth of Dietrich Fischer Dieskau and the Lady of Elena Souliotis.)

Claudio Abbado's conducting is firm, vigorous, balanced, and well grounded in the score even on the several occasions when it strikes my ear, at least, as a bit on the quick side. The playing of the Scala orchestra is never less than good, at some points extraordinary. This might be characterized as a very well-executed, straightforward reading that trusts the music and never sacrifices the proportion of a section to an immediate effect. In the "Biechiarcani" ensemble at the end of the Banquet Scene, for example, I at first felt that Abbado was underplaying the off -beat accents in the chorus too much but, at the arrival of the heavily beat climactic phrases, realized he had shaped the section as a whole more effectively than most conductors do.

Sometimes, too, a color will be caught that seems dramatically just right, as in the chorus of Banquo's murderers. But while I was initially impressed by the reading-by its logic and by its execution--I discover, when I close the score and sit back for a more subjective contact with the performance, that this sort of flavor emerges all too seldom. Passages flow by, quite well performed, without much engaging one's emotional attention. It's a little hard to put the finger on, and perhaps I can best express the problem by saying that the performance sounds to me like one that has come about from the top down and the outside in, as the result of decisions made off the page rather than in the give-and-take of exploration among performers. This is possibly an odd outcome for a recording based on a stage performance; but at that, I have latterly seen many a live production that gave me just this feeling-though seldom realized with this high competence. I respect this reading, but I would rather listen to Schippers' (even with its extensive cuts) and, at moments, to Gardelli's, which is inconsistent but at times quite gripping. (If you wish to hear a case made for the ballet music, for example, you are better off with Gardelli, who secures far more color and creates a much clearer picture of the scenario-we realize the sequence can be made theatrically apropos.)

Abbado's principals convey much of this same sense of slightly generalized expertise. (In fact, they do much to create it-per haps I have fallen into current critical cliché by placing conductor ahead of singers in an early Verdi opera.) The two leading roles are infamously difficult, largely because of the range of expression called for. Lady M. is perhaps the more trouble some of the two because it is the less convincingly written. Much of the part is set persuasively, but in some rather important spots it tends to fall back into musical gestures of rather simplistic psychological value-"Vieni, t'affretta" and its cabaletta are especially hard to integrate, I think.

I hope it doesn't sound snide to say of Shirley Verrett's performance that it is most successful in just those moments when the writing becomes relatively "vo cal" and mono -toned, and, most especially when the vocal demands are chiefly for high -intensity output. The "Vieni, t'affretta" is in fact quite excitingly done, and her contributions to the big ensembles and to the "Ora di morte" duet after the ap parition scene make an impact. "La luce longue," on the other hand, sounds "figured out" rather than wholly performed, and the Sleepwalking Scene more or less slips away, despite some nice moments and re strained choices.

I should make it clear that there is nothing in the music Verrett cannot sing respectably. And in some important respects, her taut high -mezzo voice is a good fit for the role; her technical strengths and weak nesses tend to complement those of the sopranos Nilsson and Rysanek. She manages some fair high decrescendos and even thins out the mix for the high D flat, though a constricted one. As we might expect, though, there is not much sense of real ease or float behind the upper fourth in the voice. She very noticeably darkens vowels in the middle, where the voice sounds somewhat "covered," then switches to a brighter, edgier conformation around the upper F, which she drives at from the underside up to B and C. She gets there with it, but we are not put at ease; it's all a bit up side-down. This technical question, I think, underlies her partial success with sections like the Sleepwalking Scene or the Brindisi (where, however, she's in plenty of company), those sections where real elasticity and buoyancy of the lighter sort are called for. Bearing in mind that no one since the young Callas (who can be heard only on noncommercial discs) has completely en -

-------------

La Scala Chorus and Orchestra, Claudio Abbado, cond. [Rainer Brock, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 062, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Tape: 3371 022, $23.94.

Comparisons: Rysanek, Warren, Leinsdort Vlctr. VICS 6121 Nilsson, Taddel, Schippers Lon. OSA 1380 Souliotis, Fischer-Oleskau, Garden' Lon. OSA 13102

-------------