by Harris Goldsmith

After a delay of thirty-five years, one of the most intriguing portions

of the Toscanini legacy is offered to the public.

THE RECORDINGS that Arturo Toscanini made with the Philadelphia Orchestra in the Academy of Music between November 1941 and February 1942 constitute one of the most interesting, and one of the most controversial, segments of his unique legacy.

Released only now, thirty-five years after the fact (except for the Schubert Symphony No. 9, first issued in 1963), the recordings in RCA's new five -disc set document Toscanini's work with a renowned orchestra meticulously trained (by Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Ormandy) in a tradition antithetical to his own. Moreover, they represent a curious period in his artistic evolution, when his style was evidently midway between the much more elaborately rhetorical, lyrically inflected approach heard in many of his prewar recordings with the New York Philharmonic and the BBC Symphony and the taut, sym metrical manner we know so well from his late NBC Symphony recordings. In addition, the engineering philosophy of the Philadelphia recordings affords us a markedly different orchestral perspective.

In his later years, Toscanini's work was largely confined to one orchestra, the NBC Symphony, and to two performing sites, Radio City's unjustly notorious Studio 8H and New York's justly famous, though still somewhat overrated, Carnegie Hall. Be cause of the NBC/RCA engineers' preference for a sharply detailed, closely microphoned pickup, most of the conductor's recordings in circulation give a lopsided-and perhaps unreliable-idea of "the Toscanini sound."

Toscanini's performances, for all their sinew and clarity, were more impressively massive, more sensual tonally, and often more flexible rhythmically in sum, more interesting-than the recorded counter parts on the NBC Symphony commercial discs. It is, therefore, of crucial importance to get recordings like the Philadelphia series before the listening public.

(Another case in point is the Brahms orchestral cycle that Toscanini led with London's Philharmonia Orchestra a season before his retirement: Those performances have a tonal roundness and a communicative suppleness, as well as a variety of arresting rhetorical devices, not to be heard in the contemporaneous NBC commercial recordings. A hideous-sounding off -the -air transcription was issued recently on Turnabout; would that RCA or EMI were to honor the twentieth anniversary of Toscanini's death by releasing the excellent -sounding "official" tapes.)

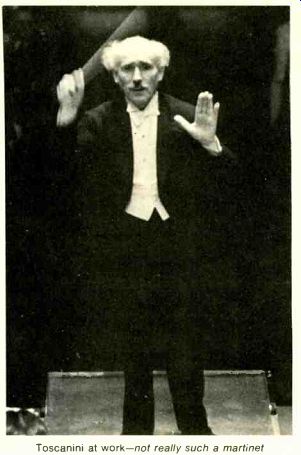

Perhaps the greatest lesson of the Philadelphia performances is that the most celebrated orchestral martinet of all time wasn't really such a martinet.

True, he was demanding, and he had an extremely high-strung temperament. But unlike Stokowski, who succeeded in making every orchestra he con ducted sound like his vintage Philadelphia, Toscanini allowed musicians to retain their own personality once those features essential to the realization of his conception of a work-good intonation, rhythmic accuracy, passionate drive, respect for the com poser's markings-were achieved. "Couture!" he would say, but he was remarkably open-minded about how his players were to "sing," unless they lapsed into willful license or slovenliness of detail.

(Then there would be fireworks.)

For all of Toscanini's well-documented technical skill, his ability to produce near -miraculous results with less than first-rate orchestras after one or two rehearsals, it probably took years of work together to produce the fully sensitized performances in his best work with the New York Philharmonic and the NBC Symphony-witness the 1929 Philharmonic recording of the Midsummer Night's Dream Scherzo, more finished than the basically excellent but rather heavy one made in 1926 for Brunswick.

That adjustment period could sometimes be shortened, with an unusually capable, responsive orchestra, as happened with the Philharmonia. The Philadelphia Orchestra, however, was, in Pierre Monteux's immortal words, "superbly trained to play very badly." Toscanini, though lacking Monteux's twinkling sense of humor, must have felt a similar lack of compatibility with the Philadelphians' style; it would be hard to imagine the orchestra of Stokowski and Ormandy adjusting easily to Toscanini.

In some of these performances, the diverging styles of conductor and orchestra fuse to produce inspired results. At other times, the results are neither ideal Philadelphia nor ideal Toscanini. The collaboration perhaps works best in the Schubert symphony. This performance-richly lyrical, flexible in tempo, hair-raisingly dramatic (quite different from the two later recordings with the NBC Symphony)-is simply the greatest I have ever heard.

The Mendelssohn Midsummer Night's Dream mu sic is almost as distinguished: a miracle of fleet virtuosity and incandescent poetry, far superior to the 1947 NBC recording. There is a tiny burble from the solo horn at the end of the Nocturne, and the extremely winged Scherzo doesn't have quite the unanimous ensemble of the 1929 Philharmonic version (although I prefer its greater lightness and whimsy).

---------- Toscanini at work-not really such a martinet

The Overture and Wedding March, while wonder fully energetic, seem a bit rushed alongside the memorable Toscanini broadcast performance of November 1, 1947, but this is magical music -making, fully worthy of documenting his incomparable way with this gossamer music.

It should be noted that Toscanini plays the suite in an order different from that which he devised for the 1947 broadcast and recording. In addition to the song with chorus (recorded in 1947 but rejected), the 1942 account includes the melodrama leading into the finale; the 1947 version of the finale merely reiterates the opening notes of the overture.

The Berlioz "Queen Mab Scherzo," always a Toscanini specialty, gets a completely characteristic ac count here--much like the NBC broadcast performance of November 10, 1951 (issued first as a self contained excerpt, later interpolated into the commercial release of the 1947 broadcast of the entire Romeo et Juliette). In the Philadelphia version, how ever, the delicate antique cymbals are reproduced sensitively, not like old pots and pans. In the Berlioz work, as in the Schubert and the Mendelssohn, we hear the typical Toscanini sound intensified by greater coloristic sensitivity, but not the customary beefy lushness of the Philadelphians. The maestro obviously appreciated tonal beauty but wasn't content with that alone-shape, direction, clarity were even more important to him.

The Tchaikovsky Pathetique is the one performance in the set about which I still haven't made up my mind. The 5/4 waltz movement and the searing finale are more flexibly phrased and richly nuanced here than in the comparatively matter-of-fact 1947 NBC recording. In the Philadelphia version. Toscanini makes more fuss over the tenuto markings in the central portion of the waltz, a detail I am coming to like more and more. On the other hand, the divergent methods of conductor and ensemble collided head on in this composition.

In B. H. Haggin's The Toscanini Musicians Knew, bassoonist Sol Schoenbach recalls how Toscanini came to the rehearsal and systematically derided the Philadelphian's "traditional" way of playing Tchaikovsky. Right at the outset, Schoenbach proudly paraded his technical accomplishment of playing the opening bassoon solo on a single breath.

Toscanini would have none of it: He wanted a more segmented effect and sang "I-ee love you; I-ee love you" to convey his idea of how that opening should sound. The record shows that Schoenbach adjusted superbly, but later on he became unnerved by another Toscanini demand.

Just before the outburst beginning the development section, there is a soft clarinet solo whose final notes are taken over by the bassoon. Many conductors cheat there and reassign those few bassoon notes to the bass clarinet. Not Toscanini, who wanted the pronounced tonal contrast and insisted that Schoenbach "play as written." "To play that!" Schoenbach writes. "I think it's marked six p's; and with Toscanini it became twenty-six p's; and it be came the biggest feat in the world: I filled my bassoon with absorbent cotton and handkerchiefs and socks!" The passage, played without mishap on the NBC record, does not come off here: The intonation is questionable, and the final low D doesn't speak on time.

There are also many passages where the playing is un-rhythmic by Toscaninian standards. The March begins at a furious clip but loses much of its effectiveness because the cross -rhythms at the beginning aren't accurate; again at bars 302-12 the dotted -note figurations sound casual, almost like triplets. Many passages are played glossily but without much internal shaping, and there are a few awkward transitions (a strange ritard at bar 170 in the first movement, a lurching hesitation at bar 175 of the March--ill gauged side breaks, perhaps?). The Philadelphia version may be more poetic and tonally refined, but the NBC conveys much more of the characteristic Toscanini rhythmic impulse and architectural sense--and the bass drum has much more exciting impact.

I have always found Toscanini's 1950 NBC La Mer and Iberia brilliantly played, stunningly reproduced, and a bit lacking in flow and spontaneity. The Philadelphia Debussy--more flowing in line and animated in tempo, less glaringly harsh sonically--puts the justly renowned later interpretations into better perspective. Though the Philadelphia performances obviously have the surface noise and sonic limitations of shellac recording, for their more spacious acoustics and more comfortable interpretations they must, I think, be preferred from an artistic standpoint.

Anyone who has heard the vibrant, richly colored Toscanini/New York Philharmonic Pines of Rome from the January 1945 pension-fund concert and the eloquently atmospheric Fountains from the memorable NBC broadcast of February 17, 1951, knows that the commercial recordings of those Respighi scores didn't do justice to his re-creations. Now, from Philadelphia, here is a luscious, colorful version of Feste romane, which similarly puts right the faulty impression left by the stiff, inflexible, hard-boiled, and uneventful NBC recording of 1949.

For me the one major disappointment in the set is Strauss's Death and Transfiguration, perhaps be cause I have heard several transcriptions of Toscanini rehearsing the piece with the NBC Symphony, in which he can be heard demanding exact realization of countless details in the score. What he was after is reflected in the 1952 NBC recording, one of his most dramatic and searchingly introspective. In this case, the Philadelphians obviously couldn't adjust to a way of playing so radically different from the Stokowski tradition. The performance has its attractions but cannot match the 1952 NBC--or, for that matter, two roughly contemporary Vienna Philharmonic accounts: Furtwangler's 1950 recording (Seraphim 60094) and Strauss's own 1944 broadcast performance (in Vanguard SRV 325/9).

In frequency response and dynamic range, the Philadelphia recordings are well ahead of their time; in surface noise, they are behind for their period, due to damage inflicted on the masters by wartime processing. According to Haggin, Toscanini rejected some of the sides because of slips in performance and imperfect instrumental balance in the sound. It was assumed that he would remake the offending sides, but the Petrillo ban on recording activities intervened. When the ban lifted in 1944, the Philadelphia Orchestra had transferred its contract to Columbia, and Toscanini eventually re-recorded all these works with the NBC Symphony. With the orchestra safely under the RCA banner once more, and with better historical perspective, it was decided to make the Toscanini/Philadelphia legacy available to the public at long last. In addition to the surface noise, there is some pitch waver in the MSND finale and the Wedding March begins flat, as if the cueing device hadn't hit full speed when the transfer was made. There is also (due to mishaps in the electro plating plant) a peculiar powdery, blasting quality in some of the heavily scored passages. But even at their worst, these recordings are never less than eminently listenable.

This set (whose five records are offered for the price of four) offers uniquely enjoyable performances of some great music plus priceless and thought-provoking documentation of one of the less-known facets of the Toscanini personality. The cliché "better late than never" emphatically applies.

--------------------------

ARTURO TOSCANINI AND THE PHIL ADELPHIA ORCHESTRA. Philadelphia Orchestra, Arturo Toscanini, cond. [Charles O'Connell, prod.. John Pfeiffer, release prod.] RCA RED SEAL CRM 5-1900, $27.98 (five discs, mono) [recorded 1941-42].

Romeo et Juliette: Queen Mab Scherzo. DEBUSSY: La Mer: Iberia. MENDELSOHN: A Midsummer Night's Dream (incidental music), Opp. 21 /61 (with Edwina Eustis and Florence Kirk, sopranos: University of Pennsylvania Women's Glee Club). Remote: Feste romane. SCHUBERT: Symphony No. 9. in C. D. 944 (from LID 2663. 1963). R. Sumas: Tod and Verklarung, Op. 24. TCHalKOVSKY: Symphony No. 6, in B minor, Op. 74 (Pathetique).

-------------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1977)

Also see:

The Parallel Careers of Edison and Bell; James A. Drake; Geniuses in sometime contact--and conflict

Link | --Link | -- Haydn at the Keyboard