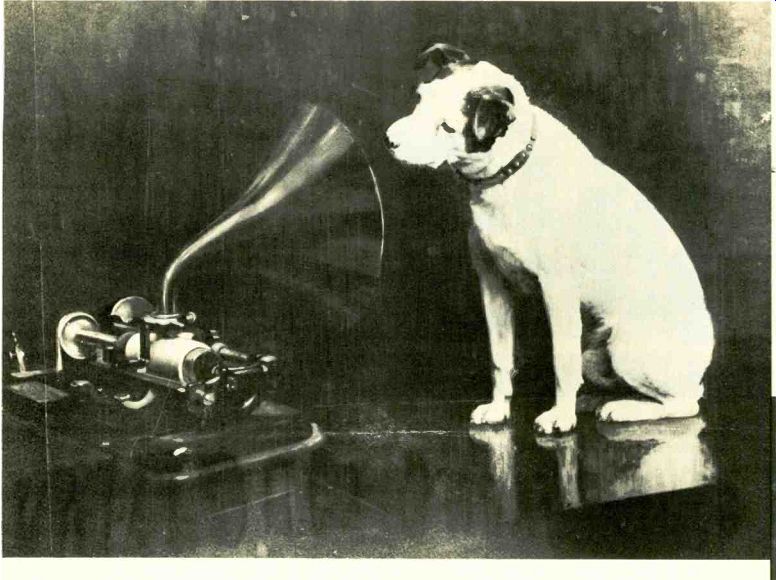

The Original Painting of Nipper--His Master's Voice first came from a cylinder

by Oliver Berliner.

NIPPER, the world's most famous dog, was a mischievous terrier with a considerable

amount of bulldog in his ancestry, accounting for his broad chest and extraordinary

strength. Mark Barraud, a scenic designer of French -Huguenot background living

in England, acquired the pup shortly after his birth in 1889. The Barraud children

promptly named him--"nipper" being British slang for a young child.

On his master's death, Nipper went to live with Barraud's brother Francis (1856-1924),

an by Oliver Berliner How his master's brush created-and revised-His Master's

Voice artist with a penchant for detail whose works had hung in the Royal Gallery

but whom fame had eluded.

The brothers Barraud were the only masters Nipper had, and neither of them ever made any recordings. But Nipper was an inquisitive dog and would sit for long periods of time, one ear raised and head cocked at an angle, studying whatever it was that caught his eye ... or, more likely, his ear.

Francis Barraud later acknowledged that seeing Nipper pose for a photo to be taken by another brother, Philip, a professional photographer with a studio in Liverpool, inspired the now -famous painting. In 1893 Francis moved to Kingston-on-Thames, where Nipper died of a stroke in September 1895 and was buried under a mulberry tree at the back of Mayall's Photographic Works.

Few people are aware that Barraud's original painting was of Nipper listening to a cylinder phonograph, not a disc record. The player in the original was a cylinder machine of the type called an Edison Commercial Phonograph, sold in Brit ain by the Edison-Bell Consolidated Phonograph Company in the 1890s. No one knows exactly what year the painting was created, although it seems to have been 1893 or 1894. Barraud tried in vain to sell it to Edison - Bell. After that the painting lay around his studio for several years. In 1899, after filing a copyright application on February 11, he found another opportunity to sell it.

The year before, my grandfather, Emile Berliner, inventor of the disc gramophone, had sent William Barry Owen to England to form the Gramophone Company, Ltd., as an offshoot of his own Berliner Gramophone Company of Philadelphia. One day, Barraud went to Owen's office bearing a print of the photograph taken earlier for copyright purposes, captioned by the painter with the words "His Master's Voice." A friend had suggested that the Gramophone Company might be willing to lend Barraud a brass "trumpet" to re place the ugly japanned -black horn on the cylinder machine, for he was never happy with the looks of the original. Owen, sensing the potential value of the painting, went further. He asked the artist to replace not just the horn, but the entire cylinder machine with the disc gramophone. A price of £50 was set for the painting, plus £50 more for sale of the copyright.

On September 18 Barraud received a Berliner gramophone to use as his model. At three o'clock on October 4, Gramophone Company representatives came to his studio to view the painting for the first time. They were pleased with it and accepted it; it was duly delivered to them on October 17. It hangs today in the board room of EMI (Electrical and Musical Industries, Ltd.), the British conglomerate. If you stand to the left of the painting, you can easily detect the cylinder phonograph over which Barraud painted the disc gramophone.

The painting is surely not great art by any standard. But it has a certain charm, and its history and impact are awe-inspiring, considering that it is virtually symbolic of an entire industry rather than of any single company. Trademark rights are now owned by various firms in their respective areas RCA in the Americas, EMI in most of Europe and Australasia, Japanese Victor (JVC) in Japan. Un confirmed rumor has it that during World War II an artist was commissioned to paint a replica, right down to the cylinder machine beneath the gramophone, to hang in place of the original for the duration, the Barraud work having been sequestered in a vault and insured for more than a million dollars.

The painting was reproduced immediately, appearing in December 1899 as an eye-catching window display in Gramophone's company -owned stores. So great was Nipper's impact that the company's name was obscured, and the firm came to be known popularly as His Master's Voice--or HMV. A lithograph of the painting caught the eye of Emile Berliner on a visit to HMV in 1900, and he quickly understood the significance of Nipper to his business. Upon his return to the U.S. he registered the design as a trademark here.

Francis Barraud earned a comfortable living painting copies of his original, including a couple of delightful watercolors. (In addition, a British Gramophone Company director, upon learning how little Barraud had received for his original work, arranged an annual pension of £250--later increased to £350-to sustain the old gentleman in his later years.) Of all his renderings, however, only the first bears the imprint of the cylinder ma chine beneath the top layer of paint.

Recently the photograph of the original painting was discovered at the British Patent Office, to which Barraud had submitted it with his application for copyright. It is reproduced here for the first time in an American consumer publication.

-------------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1977)

Also see:

The Parallel Careers of Edison and Bell; James A. Drake; Geniuses in sometime contact--and conflict

Link | --Link | --100 Years of Sound Reproduction--A chronological history

Pioneer HPM 200 loudspeaker (ad)