New Equipment Reviews (Jan. 1977)--A CONSUMER'S GUIDE

----------------

Preparation supervised by Robert Long and Harold A. Rodgers Laboratory data (unless otherwise noted) supplied by CBS Technology Center

--------

Luxman T-110, a Tuner with a Mission

The Equipment: Luxman T-110, an FM tuner in rosewood case. Dimensions: 19 by 4 1/2 inches (front panel); 10 inches deep plus clearance for controls and connections. Price: $525. Warranty: "full," three years parts and labor. Manufacturer: Lux Audio, Japan; U.S. distributor: Lux Audio of America, Ltd., 200 Aerial Way, Syosset, N.Y. 11791.

Comment: Lux Audio is a specialist in sophisticated separate components, and the T-110 impresses immediately as a sophisticated separate. Its sleek styling, its unconventional dial grille through which the pointer's illumination shows (and flashes a warning when you're not tuned to a station), the two tiny buttons and one huge tuning knob that are its only front-panel controls beside the on/ off button, its rich rosewood case-all proclaim this to be an extraordinary tuner. And it is.

There are some other controls, of course-on the back panel, since all apparently are conceived of as esoteric functions that you won't need to alter in normal use. One is only arguably of that type: the antenna attenuator.

Since the manual suggests that it be switched in only by listeners who are close to transmitters-and who still might want to switch it out to "reach for" a weak station (hence the arguableness of its placement)-the tuner was tested with the attenuator switched out. The de-emphasis switch (with one position for Dolby, one for non-Dolby broadcasts) seems even more arguable, since more stations all the time seem to be offering Dolby transmissions, while no broadcast community we know of has gone all-Dolby.

Considering both the nature of the remaining controls and the performance characteristics of the T-110, it strikes us as a tuner that, above all, is exceptionally well adapted to listening in the suburban and exurban areas neither next door to transmitters nor really remote from them-where the vast majority of the FM listening is done today. The ubiquitous high-frequency blend used to de-noise weak stereo signals is conspicuously absent. And the muting (which cuts in at 16 dBf, just about 2 dB below the point at which the tuner's attempts at stereo reception cease) rejects mono signals while they still boast signal-to noise ratios in excess of 50 dB. (The muting can be disabled, of course, and the tuner can be manually switched to mono.) The usable sensitivity (“usable" defines a quieting point at which any unit sounds about as good as a CB radio) measured at CBS labs is competitive with that of other fine tuners, but more germane to ordinary listening levels are the superlative harmonic distortion, IM distortion, and signal-to-noise ratio figures. Capture ratio is 1 dB, so multi-path interference is held well in check. (Note that there are outputs on the back panel for oscilloscope analysis of multipath, should it still prove a problem.) Similarly, the alternate-channel selectivity (72 dB) effectively suppresses strong stations that happen to be near the tuned frequency. Stereo separation is extraordinary and remains well in excess of that required of broadcasters all across the audio band.

The only mole we could find on the cheek of the Luxman T-110 is the slight rolloff in audio-frequency response from about 100 Hz down. While not unusual in FM equipment, and just detectable audibly in A/ B tests with a tuner that some consider the finest on the market, it is one point on which we must stop short of complete enthusiasm.

For the listener who is seeking to wring the last bit of quieting out of the tuner with signals of only marginal strength, the T-110 also was audibly a notch below its more expensive stalking horse in the A/ B tests, though it is better than most in this respect as well. All this means is that, though it is not the ultimate tuner for hayseeds, it is among the ultimate tuners for the in-town sophisticates with whom its over-all personality would seem most at home.

--------------

Luxman T-110 Tuner Additional Data

INPUT IN MICROVOLTS

MONO FM RESPONSE

Spectro-Acoustics' Rugged Power Amp

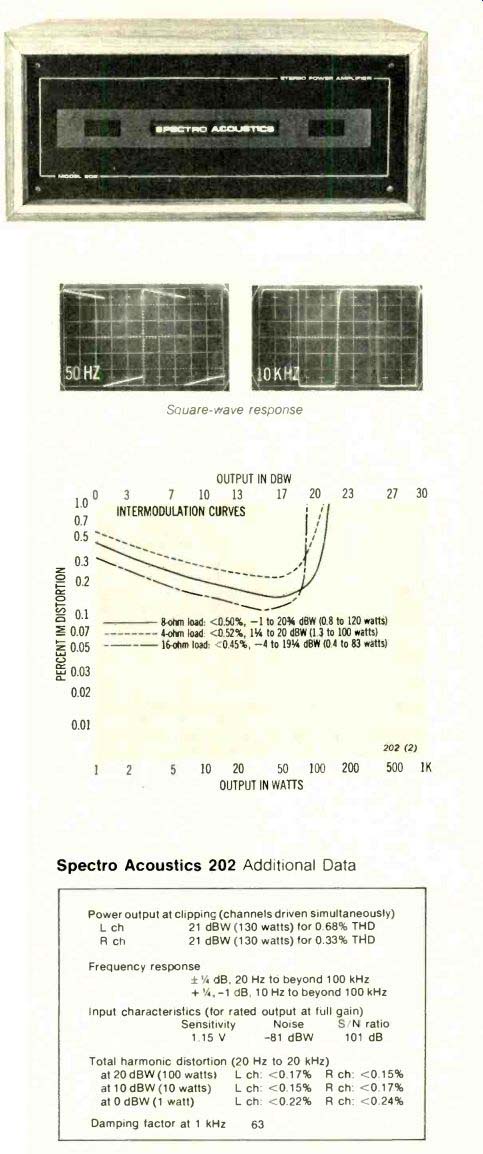

The Equipment: Spectro Acoustics Model 202, a stereo power amplifier in optional wood case. Dimensions: 15 by 6 inches (front panel): 11 1/2 inches deep. Price: $375; optional wood case, $40. Warranty: "limited," three years parts and labor. Manufacturer: Spectro Acoustics, Inc., 1308 E. Spokane St., Pasco, Wash. 99302.

Comment: The light-heavyweight division of power amps-19 to 21 dBW or so-is becoming rather densely populated these days, and this new entry from Spectro Acoustics has the requisite muscle for a contender (20 dBW, or 100 watts per channel) in addition to ruggedness and reliability. Each channel of the Model 202 is a self-contained amplifier module (called SCAMP by the manufacturer) that can be replaced in a few minutes with only a screwdriver if a malfunction occurs. The generally heavy-duty construction suggests, however, that such occurrences will be rare.

The amp has no control features (on/off switching is to be done via a preamp), and the front panel is simplicity it self. The manufacturer's logo is illuminated when the unit is on, and a light for each of the two channels flashes to indicate clipping.

According to data taken at the CBS Technology Center, the 202 has about 1 dB of midband headroom above rated power with both channels driven. Total harmonic distortion measurements are very good-in fact all are below the manufacturer's 0.25% spec with comfortable margins at the higher power levels. IM distortion is not equally low.

The figures for the neighborhood of 1 watt (where the amplifier often will be driven in normal listening) are somewhat higher than we are accustomed to seeing in an amplifier of this class and increase as power output drops. In this area they exceed the 0.25% spec. It is difficult to say whether or not IM of this magnitude noticeably impairs the amp's listening quality. When we compared the sound of the Spectro Acoustics 202 with that of an amplifier of similar ratings (but less IM), the differences we noted were subtle indeed-although the model with lower distortion won out by a whisker.

Frequency response is very good; performance with respect to noise is excellent. Sensitivity measures 1.15 volts in for 20 dBW out-a good match to typical preamp outputs. Damping factor is high. Though the lab measures it at barely half the manufacturer's rated value, it is well into territory where further increases can't be expected to make any audible difference.

Listening to the Spectro Acoustics 202 confirms a higher regard for the product than for its rather optimistic specs; the amp sounds just fine. It controls the loudspeakers well and does nothing audible to draw attention to itself. This amp can effortlessly pour out clean audio all day long. And its ruggedness and ease of repair (if something does go wrong) are worthwhile plusses.

--- Square-wave response

Spectro Acoustics 202

Additional Data

Power output at clipping (channels driven simultaneously) L ch 21 dBW (130 watts) for 0.68% THD R ch 21 dBW (130 watts) for 0.33% THD Frequency response

A Super-Subtle Pickup from Supex

The Equipment: Supex SD-900/E Super, a stereo moving-coil phono cartridge with elliptical stylus. Price: $150. Warranty: "limited," one year parts and labor.

Manufacturer: Supex Audio Products, Japan; U.S. distributor: Sumiko, Inc., P.O. Box 5046, Berkeley, Calif. 94705.

Comment: Of all cartridges, moving-coil types are among the most exotic and fussy. In addition to their relative rarity (they are made by just a few companies and are not widely distributed), they typically require high tracking forces, produce minuscule output voltages (requiring the use of a step-up transformer or extra preamplification), and must be returned to the factory for stylus replacement. Yet they are in many respects quite impressive, and a significant number of listeners find enough virtue in moving-coil cartridges to pay premium prices for them.

The Supex SD-900/E Super is unusual even among moving-coil designs, for its range of tracking force, while narrow at 1.2 to 1.7 grams, is fairly light and its output voltage (0.072 millivolt per centimeter per second, as measured at CBS) is such that it can very nearly be used in direct connection with a quiet, high-gain preamp. In our experience, however, the pickup's high output is put to better use in improving the signal-to-noise ratio that can be obtained with a transformer or pre-preamp.

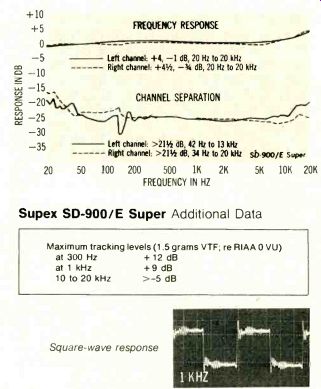

The CBS labs verified that the unit is capable of tracking full-range sweep tones at the minimum tracking force. The remainder of the tests were carried out at the recommended value of 1.5 grams. Published response (10 Hz to 50 kHz, ±3 dB) also was verified within our test range.

Measured midrange separation is very good at around 25 dB; though some other pickups may produce slightly better numbers in this test, a higher number should not be expected to produce audibly improved performance. More important to us, the separation is consistent, remaining at 20 dB or better from 40 Hz all the way up to 20 kHz. Low-frequency resonance (measured in an SME tone arm) is close to the ideal frequency at 10 Hz, and, as one would expect, we experienced no problems with warped discs or heavy modulation at low frequencies.

The stylus tip is an elliptical diamond that, under the microscope, measures 16 by 8.6 micrometers (0.7 by 0.4 mils), and in this examination it reveals excellent symmetry, geometry, polish, and alignment. Though (as the stylus shape suggests) the SD-900/E was not designed as a CD-4 cartridge, its response was checked out to 50 kHz with the JVC test record the lab uses for such cartridges. This test confirmed that the rise toward 20 kHz in our graph does not represent the high-frequency resonance, which appears to be above 45 kHz. In fact both response and separation in this range are comparable to those of many CD-4 cartridges; more important, the resonance of the pickup is (as the importers claim) well beyond the audible range.

In the square-wave test the SD-900/E Super shows a fast rise with moderate overshoot and some ringing, but only in inaudible ultrasonic regions. The other lab data re veal figures typical of most high-quality phono cartridges.

Whether the extremely low output impedance of this pickup (3.5 ohms) has anything to do with its sound is a matter of conjecture. We suspect that it contributes to a better interface between the cartridge and the preamplifier into which it works.

The sound of the Supex is without a doubt exceptional, but not in a way that seizes one's attention at first. On the contrary, the unit possesses a rare subtlety. Upon first acquaintance, the listener is tempted to simply accept it and think, "Yes, that is the way music sounds." But after listening to a familiar record for a while one begins to notice the precision (or lack of it) in musical ensembles-because the transients that result when the various instruments make their attacks are separately reproduced rather than smeared together. Also unusual is the ability of the Supex to keep soft instruments clear when loud ones are playing.

Polyphony is reproduced as an interplay of voices rather than a wrestling match, with one voice dominant at a time and the others struggling for space. In short, the listener and not the cartridge decides what features of the music are worthy of attention. We were amazed to find recorded textures that had previously struck us as excessively dense and reverberant now airy and well defined. Nothing is spectacular; it is all simply there.

Without entering the great debate over principles of transduction, let us say that we find this to be one terrific phono cartridge. It has its fussy side, but what virtuoso hasn't? Perhaps most squarely in the virtuosic tradition, the Supex Super makes it all seem easy.

CHANNEL SEPARATION

Square-wave response

Nikko's Best Receiver Yet

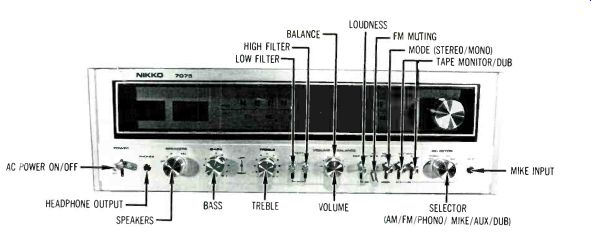

The Equipment: Nikko Model 7075, an FM/AM stereo receiver in wood case. Dimensions: 19 by 4 1/4 inches (front panel); 13 3/4 inches deep plus clearance for controls, connections, etc. Price: $399.95. Warranty: "limited," three years on parts, two years on labor, transportation not included. Manufacturer: Nikko Electric Mfg. Co., Ltd., Japan; U.S. distributor: Nikko Electric Corp. of America, 16270 Raymer St., Van Nuys, Calif. 91406.

Comment: The Nikko components we have examined in the past seem to have fallen into two categories. Most have been budget models, with all that the term implies; at least one has been an attempt at something grander in which the more striking features were accompanied by others of much less merit. The 7075 is another matter. It is a good mid-priced receiver, designed from stem to stem with an eye for features and performance levels that are consistent with that price point. Therefore-and though it is by no means the fanciest Nikko we've assessed (there are in fact two more powerful and expensive models in the current line)--the 7075 is the most consistent, capable, and attractive Nikko we've reviewed to date.

The controls are well-organized and functional. They include both high and low filters (the former must De used to cancel FM multiplex noise, since there is no "blend" feature) and an FM-muting switch. Monitoring-and dubbing--with two tape decks is provided for. The tone controls have calibrated detent stops for repeatable settings.

And--perhaps most important--handsome lever switches are used in place of the pushbuttons that we find irksome because they are difficult to label unequivocally, and hence to use. With the 7075 you are left in no doubt about the control settings.

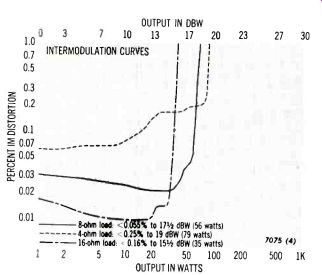

The amplifier section's output rating (38 watts or 16 dBW per channel) puts it in the class that might be characterized as ample for one speaker pair and adequate for two, under typical home conditions. Actually the CBS tests show this rating, and the related 0.5% distortion ratings, to be conservative. The amp can pump out about 3/4 dB more power before clipping, and distortion still stays somewhere around one-tenth of the rating point at that power level. And even at 20 dB below rated power both harmonic and intermodulation distortion remain in the 0.05% range or better.

Noise measurements are good (numerically not quite as low as the published specs, though with our worst-case, full-gain test method this is normal), as is phono overload.

The only feature in the amp/ preamp area that we don't think much of is the (mono) mike input. After having made similar statements about virtually every receiver so equipped that we've reviewed, we can only repeat that per haps a receiver is just not the place for a mike input. That on the 7075 can't be mixed with other inputs (as it can on most mike-input models), though it can be fed to the regular tape-recording jacks (which is unusual). It therefore is appropriate for public-address use and for mono speech or other recordings not requiring mixing-neither of which strikes us as having much to do with high fidelity.

The tuner section is comfortably good. An exception to that description is the excellent channel separation in stereo, but the emphasis here-as in the rest of the de sign-is on keeping performance bobbing buoyantly above the mainstream of the acceptable, not on taking wing into any airy heights. Some might call this level of competence "unspectacular," but that would be missing the point. The 7075 does well exactly the job it is designed to do; that is a valuable faculty and one that should find a ready market.

------------

Nikko 7075 Receiver: Additional Data

A High-Definition Pre-Preamp from Mark Levinson

+

The Equipment: Mark Levinson JC-1DC Moving-Coil Cartridge Preamplifier, a pre-preamp in metal case. Dimensions: 5 3/4 by 7 1/2 inches plus clearance for connections (top); 2 inches high plus clearance for controls.

Price: $100. Warranty: "full," five years parts and labor. Manufacturer: Mark Levinson Audio Systems, Hamden, Conn., 06514 USA.

Comment: Moving-coil phono cartridges (such as the Supex model reported on in this issue) characteristically have low output and impedance, preventing them from being used effectively in direct connection to a normal 47,000-ohm phono input. The conventional solution to this problem for a long time has been the use of a transformer that steps up the voltage and impedance and thus provides a better match. This approach works quite well, but since transformers possess irreducible nonlinearities larger than those of active amplifying devices (such as transistors) some audio designers thought that an extra high-gain stage would improve performance with respect to distortion. They were right, although early pre-preamps (so called because their outputs are delivered to a normal phono preamp) had too much noise. More recent refinements appear to have this difficulty under control.

The Mark Levinson JC-1DC is described as a low-feedback Class-A design with high slew rate and open-loop bandwidth. As such, it would be expected to show very little harmonic distortion, and this is in fact the case. Even at the extremely high signal levels (200 millivolts output) used by CBS labs (and the manufacturer) to provide re liable data, the pre-preamp produces barely half of its rated 0.1% THD at 20 kHz and even less elsewhere. IM distortion (measured at 100 millivolts output) is likewise well Frequency response is flat out to 20 kHz falling off by a mere 1 dB at 40 kHz. The unit shows a slight rolloff (only 3/4 dB) at 20 Hz and reaches -1 dB at 16 Hz. The gain of the JC-1DC is adjustable via a two-position switch; the high position gives a nominal 47 dB (49 measured), the low position 30 dB (31 1/2 measured). Although the lower gain is adequate for all but a few moving-coil cartridges, all lab data were taken at the high setting.

Measured noise performance (-69 1/2 dB re 1 millivolt in put, input terminals shorted or open.-70 dB with 30-ohm source impedance) is excellent for such low signal levels.

The manufacturer claims about 10 dB better performance, but it should be borne in mind that noise measurements at these low levels are sensitive and that small differences in technique can have large effects on the results.

With a cartridge connected to its input and its output connected to a phono input, the noise that the Levinson delivers to a speaker is slightly less than that produced when a standard magnetic cartridge is connected directly to an identical phono input.

In putting the JC- 1 DC to use, a few caveats are in order.

The unit is sensitive to hum and (as the instructions suggest) must be placed well clear of power transformers and motors. Our sample is slightly microphonic and so should be kept away from loudspeakers as well. Since power is provided by four D cells (alkaline types are recommended) and there is no pilot light (that would take far too much current), you must remember to switch it off (turn the gain down first!) when you're finished listening or you will be buying a lot of D cells. In normal use, one set is good for about a year.

But the bottom line for a fairly exotic piece of audio hard ware such as this has to be its sound-although all we have to comment on in this case is the lack of it. We were not able to detect any audible "effects" that we could trace to the Levinson. It is quieter than all but a few phono stages, which is remarkable considering the high gain, and its definition should beat any transformer hands down. If your low-output phono cartridge is looking for a work partner, the JC-1 DC is one you should consider.

-------------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1977)

Also see:

The Parallel Careers of Edison and Bell; James A. Drake; Geniuses in sometime contact--and conflict

Equipment Reports (March 1977)