Though unfinished, the underground quarters of the new musical-scientific institute in Paris already has the welcome mat out for the future-minded.

by Roy McMullen

[Roy McMullen, an American resident in Paris for years, is the author of Mona Lisa: The Picture and the Myth.]

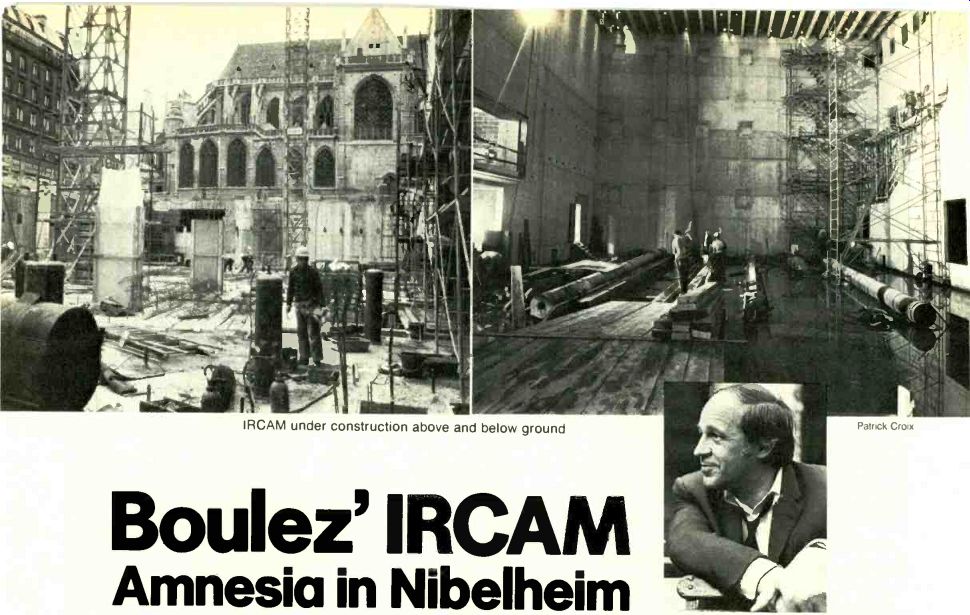

-------- IRCAM under construction above and below ground; Patrick Croix.

IF YOU'RE BORED by anti-modern Calamity Janes, weary of modish jeremiads against science and technology, and in general fed up with pessimism, you should visit Paris this summer. Specifically, you should head for the Right Bank and Pierre Boulez' new Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique-IRCAM in the lingua franca of initials. Here you will find a most stimulating symbol of faith in our cultural future.

You will also find evidence that Boulez has ended his Thirty Years' War with the French musical Establishment. He is obviously determined to develop IRCAM into one of the principal achievements of his career. When his contract with the New York Philharmonic runs out with the current season, he will be free of major conducting engagements except for the one with Bayreuth and will be a Paris resident. In fact, although he in tends to keep his house in Baden-Baden, he has al ready taken an apartment on the thirtieth floor of one of the controversial skyscrapers near the Eiffel Tower, and he has begun to refer to himself, rather emphatically, as an inhabitant of the Fifteenth Arrondissement.

Naturally, IRCAM has its detractors. Since it is attempting an alliance of art with science and technology, it has been criticized as a musical revival of the Bauhaus. Since it will be installed (by June, if the present building tempo is maintained) in a labyrinth below street level, it has provoked derisive allusions to Nibelheim, to Orpheus in Hades, and to an underground ivory tower. More seriously, it has been called a misuse of public money by an elitist minority. Boulez, however, is accepting all the disapproval with the serenity of a man who has at last obtained the tool he has al ways wanted, and who knows exactly what he is going to do with it.

"The creator," he explains, "working with just his intuition, is powerless to provide a complete translation of musical invention. He must collaborate with the scientific research worker in order to envisage the distant future, to imagine less personal, broader solutions. As for the scientist, we are of course not asking him to compose, but to conceive with precision what the composer, or instrumentalist, expects of him, to understand the direction contemporary music has taken, and to orient his imagination along these lines. In this way we hope to forge a kind of common language that scarcely exists at present, while training a staff that will be basically oriented towards musical creation." Extending, ramifying, and marvelously complicating the interdisciplinary aspects is the fact that IRCAM is one of the four components of the huge Centre National d'Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou, which was inaugurated in January. (It is usually referred to as the Centre Beaubourg, be cause of the name of the square on which it stands.) The other parts of the Beaubourg complex are a public library, the National Museum of Modern Art, and a center for industrial design, architecture, town planning, and visual communications.

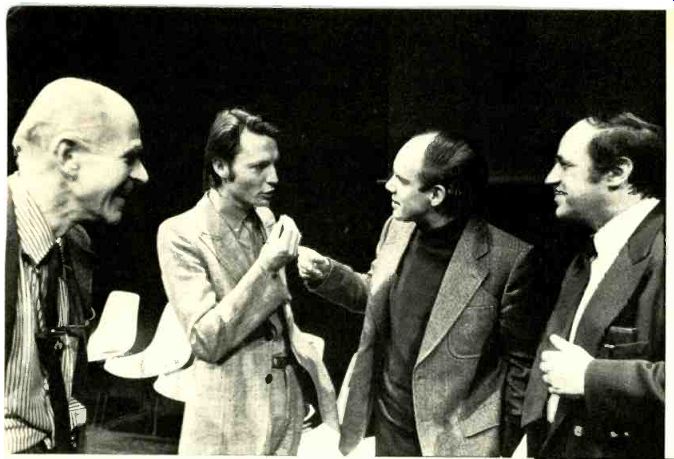

While waiting for the completion of its underground quarters, the institute is open for business in an old building next door. Here the computers are already humming and the major departments organized and functioning. Boulez, as director, keeps an eye of everything. But he is being helped by a remarkable international staff, which will have fifty-four permanent members when the budget limit is reached, of composers, performers, researchers, technicians, and far-out thinkers. Al though many of these people have other commitments to fulfill, from now on they will all be spending a lot of their time in Paris.

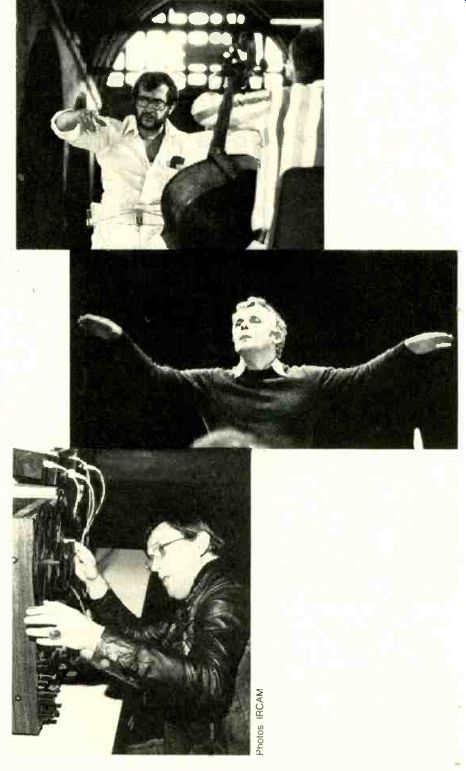

The Instruments and Voice Department is headed by Vinko Globokar, whose frequently facile clowning with his trombone has perhaps obscured his merits as an amusing, knowing com poser, a fantast capable of drawing on nearly anything from the folk music of his native Yugoslavia to some of John Cage's drolleries. The mission of the department is to discover, invent, and disseminate innovations in traditional Western instrumental and vocal techniques; study Asian and other non-Western techniques without condescension and without "colonizing" them; develop new instruments or devices that radically transform old instruments; and investigate the psychology, the physiology, and the role of the performing musician in contemporary society. Globokar hopes to encourage an outburst of "physical and psychic energy" and, finally, a sort of sonic humanism. He believes that conventional musical sounds have become "grayer and grayer" and therefore "no longer capable of communicating a message." The Electroacoustic Department is being run by Luciano Berio, who is thus updating an early phase of his career, when he was a founder, with Bruno Maderna, of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale in Milan. He is charged "with studying the means of processing electronic sound production in real time and introducing digital techniques for generating and processing signals (particularly intermodulation and voltage control techniques)." That may not suggest much in the way of orphic pleasure. But Berio has promised, in less bristling language, that his department "will be as flexible and as open as possible in order that each com poser or research worker can invent, create his ideal studio." And he adds that IRCAM, although interested in analysis, is not "a hospital for sick music." A French information expert and composer, Jean-Claude Risset, is in charge of the Computer Department. His assignment is to do research on sound and the synthesis of sonic material with computers; study the man-machine relationship in the field of music, improve methods for computerized composition; and probe the many psycho-acoustic phenomena that affect our enjoyment of music. His equipment also takes care of IRCAM's general need for scientific calculations, data processing, circuit simulations, trial runs, and automatic controls.

------------IRCAM's cast: at top left, Max Mathews, Jean-Claude Risset,

Gerald Bennett, and Boulez; above, top to bottom, Luciano Berio, Vinko

Globokar, and Michel Decoust.

The American composer Gerald Bennett, formerly director of the conservatory of Basel, heads what is called the Diagonal Department. This, as its odd label implies, slants across the organization chart, coordinates the various branches of re search, and instigates the transplanting of techniques from one department to another. In short, it needles Globokar, Berio, and Risset into remaining aware of each other. It also does some investigating on its own, notably into the links between music theory and other areas of inquiry.

Two years from now, when the IRCAM research has borne usable results, the Pedagogic Department will start to function. It will study ways to train people for a new music and will provide advanced students with the technical facilities they need for becoming familiar with new instrumental techniques and new methods of composition. Boulez hopes that what emerges will have a beneficial effect outside the avant-garde and will eventually help to make all sorts of music-ancient and modern, Western and non-Western, more accessible.

The head of the department will be the French composer/conductor Michel Decoust, who has a brilliant record as the innovating director of a conservatory at Pantin, on the outskirts of Paris.

IRCAM staff members know perfectly well, partly because of unfriendly reminders, that what they are attempting is by no means an earthshaking novelty. After all, people have been inventing electromechanical and electronic musical instruments since the beginning of the twentieth century. Synthesizers will soon be almost as common as pianos. Popular musicians who may never have heard of sine and sawtooth waves are turning out, with the help of record-company engineers, some fascinating new sounds. Similar operations have long been under way in the well-equipped music departments of American universities, in the studios supported by European radio networks, in the research divisions of computer manufacturers, in the laboratories of individual scientists, and so on.

Moreover, in this context Paris was not exactly a backwater when Boulez decided to come home.

Here, in 1948, Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry dreamed up the whole concept of tape music.

Schaeffer's Groupe de Recherches. Musicales is still active, financed by Radio France and under the direction of the imaginative Francois Bayle.

Pierre Barbaud has been quietly working at computerized composition for some twenty years. So, of course, has Iannis Xenakis, who since the early 1960s has been doing a good deal of fundamental musical research with a team of mathematicians and scientists.

In view of all this, isn't IRCAM largely redundant? Isn't it, like the rest of the Centre Beaubourg in many minds, too big and too concentrated? Per haps a manifestation of what has been called, by conservative French critics, I'imperialisme boulezien? Wouldn't the French government have been wiser, and at any rate fairer, if it had distributed its largesse? Boulez has answered such questions over the past year in Paris press conferences and interviews. Other research centers, he argues, are in general too small and too dependent; they are cells grafted onto large organisms with different priorities. For example, the electronic studios attached to radio networks are subject, so far as diffusion is concerned, to program policies that mostly ignore electronic music; and the studios in American universities are subject to the curricular imperatives of standard music departments. Also, he says, these smaller centers tend to isolate disciplines, to be staffed either by musicians or by scientists and technicians. IRCAM, by contrast, is large enough and independent enough to have its own priorities and to assemble musicians, scientists, and technicians under one roof.

Boulez drily denies that he has Napoleonic ambitions. IRCAM; he points out, is getting only 10% of the Centre Beaubourg's budget this year, and there is no plot to annex or destroy other French musical-research efforts. He insists, however, on the need to keep his institute reasonably big.

"Sprinkling government subsidies," he says, "is a technique loved by politicians, for it supposedly keeps everyone happy. But it produces very small results. I'm persuaded that one must concentrate the means available." He insists, too, on the international character of IRCAM. Risset has been able to get his computers going in a useful, musical way largely because of programming material from Stanford University, sent over without payment. Other generous help has come from Michigan State and Columbia.

Nicholas Snowman, cofounder of the London Sinfonietta, has been working with Boulez on concert programs and on the knotty general problem of coordinating the manifold activities of IRCAM.

Particularly valuable on-the-spot assistance in scientific and technological matters has arrived from Max Mathews, research director in acoustics and psychology at Bell Telephone Laboratories, and from acoustics expert Manfred Schroeder, director of the Physikalische Institut of Gottingen and also a Bell Labs man.

More and more foreign musicians and scientists will undoubtedly discover the peculiar, exhilarative charm of IRCAM. Boulez is planning a system of short-term contracts for research that should at tract thesis writers and professors on sabbatical leave.

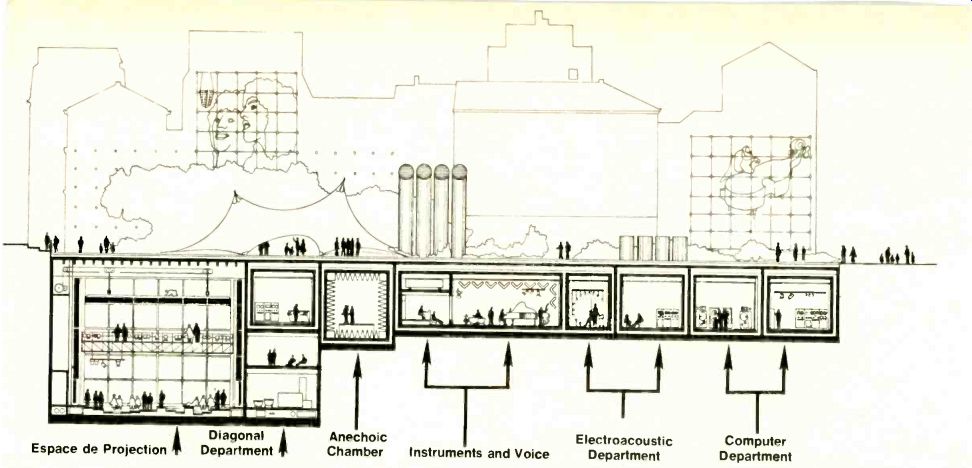

Another major attraction is bound to be the building itself. Designed by the Italian Renzo Piano and the Englishman Richard Rogers, who were the architects for the Centre Beaubourg as a whole, it will be the fanciest, but most functional, structure of its kind. In fact, it is already close enough to existing to permit the present tense. It occupies an area below a piazza between the main Beaubourg building and the Gothic church of Saint-Merri. Its flat dimensions are about those of a football field, and its deepest point is more than fifty feet. The whole structure floats in thick insulating materials that augment the sonic isolation provided by being underground. There are studios, laboratories, offices, and study rooms. A glassed-over zone is supposed to prevent claustrophobia.

The most interesting part is an auditorium called the Espace de Projection that has room for about four hundred people. This, in Boulez' words, is a "unique tool, spectacular in every sense of the term." It's a combination of concert hall, experimental theater, recording studio, and scientific laboratory, as flexible as an accordion and as gadgety as the Concorde. The ceiling goes up and down in three separate sections, metal room dividers roll and unroll, and nearly two hundred pivoting, prismatic elements reflect or absorb sounds as desired. These devices are controlled by an electronic console that eventually will he coupled to a computer, so that the resulting spatial and acoustical configurations can be programmed.

Mobile ladders and bridges for performers, batteries of colored lights, and a wide variety of speakers, tape machines, and whatnots add to the protean potential.

The activities of IRCAM will not be limited, however, to what goes on in its headquarters. A mobile unit, carrying experimental equipment, will have the mission of spreading the good avant garde word, and new music, in the French provinces and soon in other European countries. Its work will be supplemented by a documentation service that will send out specialized publications, tapes, and audio-visual material to anyone who is interested. (Everything will not be free. For details write to IRCAM, Documentation Service, 31 Rue Saint-Merri, F-75004 Paris. Some good papers should emerge from an IRCAM-sponsored symposium on musical psychoacoustics scheduled for July 11-13.) The institute is also functioning, in a surprisingly ambitious way, as an impresario of modern music. With the opening of the Centre Beaubourg in January, it launched a gigantic year-long festival, Passage of the Twentieth Century. In a preface to the program, Boulez explains the purpose of the festival:

Before devoting itself completely and exclusively to research, IRCAM wants to focus, in public. on what exists as an immediate or distant reality and also on what ought to exist in the perspective of the future .... Let us together consider the passage of this century. with the certitudes it has abundantly produced, and the uncertainties it has also produced in profusion.... What we have as our constant aim is the transition from works that have become models to experiments that are courageous and adventurous.

To be performed throughout the year are works of ninety-one composers, ranging in time from Debussy: Mahler, and Schoenberg to the present, and in style from impressionism and expressionism to computerism. Some of the evenings are "ateliers" in which a composer rehearses and explains one of his compositions.

--------A cutaway view of IRCAM. Note the hoists for the Espace

de Projection ceiling, adjustable in three independent sections. The

Instruments and Voice rooms include recording studios, depicted here

during a session. Above the recording console area are vent pipes. The

artist has included ideas for decorating the barren walls that will enclose

the IRCAM plaza.

The concerts are being given in a half-dozen Paris halls by fifty-six soloists, eight. French orchestras or chamber groups, and eleven foreign formations. Among the soloists are Cathy Berberian, Yvonne Minton, Aurele Nicolet, Heinz Holliger, Daniel Barenboim, Maurizio Pollini, Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman, and Mstislav Rostropovich. The foreign ensembles include the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Alban Berg Quartet of Vienna, the Composers Quartet of New York, and the Schola Cantorum of Stuttgart.

Of particular interest are the concerts presented by the Ensemble Inter Contemporain, the new twenty-nine-man orchestra created by the French ministry of culture for the performance of contemporary music. Although Michael Tabachnik is its regular conductor, Boulez is its director. And al though it has no official role in IRCAM, Boulez clearly regards it as another essential tool for his Parisian operations.

A striking aspect of these operations is their consistency with what was going on in Paris about twenty years ago, when the animator of IRCAM was heroically animating his first organization for new music, the Domaine Musical. Except for size, the IRCAM festival is a replica of the series of concerts presented by the Domaine, which also mixed contemporary experiments with twentieth-century works regarded as "models," as points of historical reference. The Ensemble Inter Contemporain resembles the old ensemble and has the same aim of helping young composers to be heard.

Plainly, Boulez has come home to pick up, with more massive means, where he left off. At fifty-two he is a bit mellower, and much more polite, than he used to be; he is no longer what Jean-Louis Barrault once (affectionately) called him: "a cat with all its claws out." Even so, he has not lost his old convictions. One could have expected a weakening of modernist combativeness in a middle-aged man who had spent years as a highly successful conductor of mostly traditional music in London, New York, and Bayreuth. But nothing of the sort has happened.

On the contrary, the combativeness has become stronger, in the sense of taking in more territory.

The Boulez of the old days in Paris was noticeably unenthusiastic about electronic music and about attempts by composers to make use of modern science and technology. In the perspective offered by IRCAM, he was in many ways a conservative musician. Why is he so markedly less conservative now? So interested in what he might have dismissed as naive gadgetism and scientism when he was running the Domaine Musical? A simple explanation is that the gadgets have been improved to the point of providing a previously unsuspected opportunity for a musical imagination. Another explanation is that Boulez has evolved in a predictable way. He was educated, it should be remembered, partly as a mathematician and an engineer. He has always been an uncompromisingly intellectual musician, a believer in structure and precision. And while an analogy between serialism and computerized composition will not hold much water, one can see how a sensibility that was once fiercely responsive to Schoenberg's method could finally become interested in electronic equipment.

And there is a deeper consideration. Boulez has long been preoccupied by the problem of historicism in modern music. Six years ago, in a strangely passionate article on the subject for the French magazine Musique en Jeu, he announced his intention to "praise amnesia." He grants, of course, that composers cannot really forget the past of European music and traditional instruments. But he obviously feels that they can benefit from trying to do so. They can take a fresh, scientific--hence a-historical-look at the fundamentals of their art. They can do what IRCAM is doing.

-------------

(High Fidelity, Apr. 1977)

Also see:

Link | --Link | --The New Releases--The Perilous Path to Soprano Superstardom; Heroic Voices from Pioneer Days

Music in USA--Words into Music

Link |