The Perilous Path to Soprano Superstardom

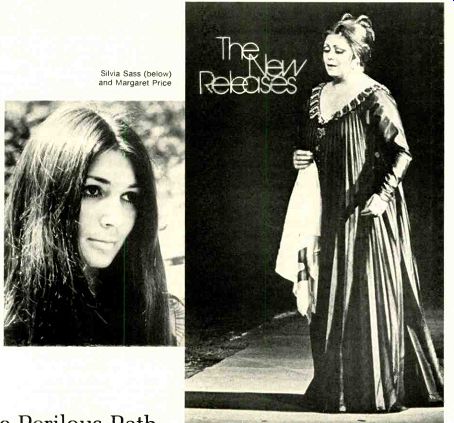

Mozart recitals by Silvia Sass and Margaret Price document the promise and problems of two of our fastest-rising sopranos.

above: Silvia Sass (below) and Margaret Price

by Dale Harris

A GREAT DEAL of Mozart's vocal music, especially that designed to display the skills of specific artists, presents real problems for contemporary singers. Nearly everything in the pair of recently released Mozart recitals by Silvia Sass (Hungaroton) and Margaret Price (RCA Gold Seal) calls for a combination of line, weight, and agility-not to mention style-that is only rarely encountered these days.

The number of times one has heard a Donna Anna who could sing with genuine facility the concluding florid measures of "Non mi dir" is small indeed. A technically proficient Idomeneo Elettra is even rarer. And if in the last generation there have been several Constanzes who could negotiate the technical difficulties of Martern oiler Arten," the reason is that, as with the Queen of the Night, the role is almost invariably entrusted to a piping soprano leggiero rather than to a singer with the amplitude of tone implied by the music and the dramatic situation.

Price and Sass, however, are exceptional in that both have sizable voices-the former is a Desdemona, the latter a Tosca-and yet can handle with ease all the fioriture demanded of them by this music. Price simply sails through the allegretto section of "Non mi dir" and dispatches Constanze's aria without turning a hair, while Sass makes Elettra's bravura vengeance aria seem like child's play. (Each of them, incidentally, can lay claim to that increasingly rare accomplishment, a recognizable trill.) No wonder that they are among the most highly touted young singers of today.

Nevertheless, I fear that my admiration for them as artists falls somewhat short of my appreciation of their nimbleness. In the case of Price there are insurmountable barriers to my enjoyment of her skills, chief among them being the whiteness and hootiness of her tone. However, in light of her worldwide renown I realize that mine is a personal reaction, and for those who do not find such straight, fluty tone objectionably un-sensuous this recital may, of course, prove rewarding.

Even so, the breathiness of Price's vocal production (listen, for example, to the sound of air escaping as she attacks the top A on "Pein" in the Entfiihrting aria) might be adjudged a drawback by others be sides myself. The same could be said for her frequent recourse--discreet but damagingly evident--to the intrusive aspirate as a means of getting from note to note in slow music. Another problem is the blandness of her interpretations, though I would say this is the concomitant of her vocal method, which, admit ting of little coloristic variety, has the consequence of making the Countess. Susanna, and Cherubino (or, if you like. Donnas Anna and Elvira) all sound much the same.

Whatever the reason, Price's lack of vocal personality becomes all the more evident as soon as one turns to the Sass recital, where one immediately hears a more distinctive and interesting voice, though I would not call it a particularly attractive one. Sass, however, will be twenty-six this year and is therefore about a decade younger than Price. Thus she is in the early stages of what could he a highly successful career and is still, I suppose, capable of developing.

Her gifts right now are considerable. She has a good stage presence, great physical attractiveness, and a voice not merely engaging and flexible, but also powerful. I have no idea when this Mozart recital was recorded. (How I wish record manufacturers would offer such information!) But the voice is very much fresher and more malleable than the one I heard-with, I must confess, a certain amount of mis giving-last summer at Aix-en-Provence in Tr(' viato.

Here Sass sounds fluent and poised. Apart from the noteworthiness of her agility, she is also impressive when it comes to legato singing, an especially fine ex ample of which may be heard in "Ch'io mi scordi di te" at the words "mancandova," where she binds all the notes of a long descending phrase into a seamless whole.

None of the latter skill was evident at the live performance I attended, and even in the present recital there are obtrusive weaknesses in Sass's technique that give one pause. Above all, her tone is excessively covered and she shows, possibly as a result of this, a disturbing lack of ease in the top register. (Like Price, she is weak at the lower end of the staff.) Despite her youth she already seems to have difficulty in producing high tones unless these are either very loud or very soft. Her soft high notes, moreover, are not really securely supported and lack color. Whether this is eradicable (or even whether Sass is aware of the problem) I don't know, but I find it disconcerting to think of so young and technically vulnerable a voice embarking on roles like Tosca (her Met debut) with Norma and Elisabeth de Valois to come next season (at Covent Garden and Hamburg, respectively).

In both recitals the often elaborate accompaniments are well played. Hungaroton offers texts, though only in Italian, and helpful notes. RCA Gold Seal offers no texts and deplorably thin notes.

MOZART: Operatic and Concert Arias. Silvia Sass, soprano:

Hungarian State Opera Orchestra, Ervin Lukacs, cond. [Janos Matyas, prod.] HUNGAROTON SLPX 11812, $6.98.

Idomeneo: D'Oreste, d'Ajace. Concert Arias: Ah, lo previdi. K. 272; Ch'io mi scordi di te. K. 505 (with Andras Schiff, piano); Bella mia tiamma, K. 528.

MOZART: Operatic Arias. Margaret Price, soprano; English Chamber Orchestra, James Lockhart, cond.

RCA GOLD SEAL AGL 1-1532, $4.98.

II Re pastore: L'amer6 sar6 costante. Idomeneo: Idol mio. Die Entkihrung aus dem Serail; Martern alter Arten. Le Nozze di Figaro: Voi the sapete; E Susanna non vien Dove sono: Giunse elfin it moment° Deh vieni, non tardar. Don Giovanni. In qua eccessi . Mi tradi; Non mi dir. La Clemenza di Tito: Parto, parto.

Heroic Voices from Pioneer Days

Willem Mengelberg's incomparable 1928 recording of Strauss's Ein Heldenleben is vividly restored (or improved?) on Victrola.

by R. D. Darrell

----------Willem Mengelberg and Richard Strauss in the late Forties

ONE OF THE transcendental musical experiences of my youth was hearing Mengelberg lead the New York Philharmonic in Richard Strauss's Ein Heldenleben, a score dedicated by the composer to "Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam." And it was only a few years later that I had the opportunity of reviewing the Mengelberg/Philharmonic recording in its original Victor 78-rpm edition.

That review-in the March 1929 Phonograph Monthly Review-was so enthusiastic, and the imprint of Mengelberg's eloquence so deeply embedded in my mind, that I'm undoubtedly still biased in evaluating the new RCA Victrola reissue. The reading en thralls me all over again with a dramatic conviction and continuity unmatched for me by any later recording, even in such deservedly admired versions as those by Krauss (1952 mono, just reissued in Lon don's Treasury series as R 23209), Reiner (1954), and Beecham and Ormandy (both 1961). And I must doubt that any of the accounts I haven't yet heard by Hail ink (1971), Kempe (1974, as yet available only abroad), Karajan (1975, the first in quadriphony), and Solti (just announced)--are likely to change my mind, at least as far as interpretations are concerned.

Yet the real point is not Mengelberg's reading as such, but how well his original recording has been transferred to LP-a question clouded and complicated by annotator Irving Kolodin's jacket-note statement that, through "new methods of computerized recovery of ... latent values, Ethel veritable sound of the Philharmonic-Symphony has been recreated as it did not exist in this recording's first is sue: Victor album M 44." Does this mean that the digital processing system invented by Thomas G. Stockham Jr.--which I had assumed was devised primarily. if not exclusively, for acoustical rather than electrical recordings-has been used as it was in the recent reissues of Caruso and Gershwin acoustical recordings? Regrettably. I have never heard the 1957 Camden LP reissue, but I have been provided with an even better means of comparison: the recent British RCA reissue, SMA 2001 (which bears a 1972 publication date, although it was not actually released until the fall of 1975). Insofar as my impressions of original sound are dependable--and I rely more on my printed words than on aural memory-the British edition strikes me as a shade truer to the original qualities, especially in string-tone warmth and over all dynamic range, both of which were considered exceptional by 1929 standards and remain impressive even today. However, despite my purist skepticism about computerized re-creations of anything not in the original recording, the American reissue does indeed suggest at least some closer approximation to what Mengelberg's Heldenleben must have sounded like in the December 1928 Carnegie Hall recording sessions.

Relative to the British LP, there is slightly but definitely more brazen bite and impact to the fortissimos, a slightly wider dynamic range, more weight to the very low frequencies, and occasionally some increase in resonance. Perhaps such qualitative differences may seem unnaturally spectacular to some listeners. But I can't honestly say that I can muster any serious objection to their enhancements of the dramatic force of both the music and the Mengelberg performance.

Whether you accept the Victrola reissue on its own merits (or for its budget price) or search out the British version, you'll be mightily impressed by the minimization of the original noise elements (now evident mainly behind the unaccompanied solo violin pas sages). the authentic Carnegie Hall acoustical ambience. the lucidity of score details (surprising only to youngsters unfamiliar with the technological achievements of 1928 engineers at their best), and beyond the incomparable Mengelbergian magic it self-the caliber of the orchestra in its first year as the combined Philharmonic-Symphony.

You may not he surprised by the earlier excellence of such familiar first-chairmen as timpanist Saul Goodman (in his rookie year), trumpeter Harry Glantz, clarinetist Simeon Bellison, and bassoonist Benjamin Kohon. But who remembers the legendary concertmaster Scipione Guidi and hornist Bruno Jaenicke? There were giants-players, conductors, engineers--in those days! If this reissued Heldenleben can't convince today's young listeners of that, nothing can.

STRAUSS, R.: Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40. Scipione Guidi, violin; New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Willem Mengelberg, cond. RCA VICTROLA AVM 1-2019. $3.98 (mono) [from VICTOR 78s, recorded December 11-13, 1928).

-------------

(High Fidelity, Apr. 1977)

Also see: