by Rosalyn Tureck

[On October 11 at Carnegie Hall, Rosalyn Tureck, celebrating her fortieth anniversary this year as a concert artist, will play Bach's Goldberg Variations on both harpsichord and piano. In June, she became the fourth American woman to receive an honorary doctorate in the history of Oxford University.]

BACH'S INVOLVEMENT with the piano was brought to light in recent years by way of an incontestable document: a voucher dated May 9, 1749, recording the sale of a Silbermann "Piano et Forte" to Count Branitzky of Bialystok for 115 Reichstaler. The receipt is signed with a confirmed signature of the salesman-Johann Sebastian Bach! This significant discovery was first revealed in the Polish music journal Muzyka ten years ago. In the July 1971 Musical Quarterly, Dr. Christoff Wolff brought it to the attention of a wider group of scholars. Yet I find that many professional musicians as well as the international music public are not aware of it.

It is high time that Bach's relationship to the piano was more widely known.

He was thoroughly familiar with the pianoforte.

This fact was rather lengthily documented in a news report in the Spenersche Zeitung of Berlin, May 11, 1747, which recorded Bach's famous visit to Frederick the Great four days earlier. It is well known that Bach tried and played several pianos Frederick possessed, but his knowledge of the pi and extended over many years previous to this visit. His pupil Johann Friedrich Agricola wrote of Sebastian's interest in Silbermann himself. And the following excerpt from notes from a 1768 treatise on the organ and other instruments by Jacob Adlung (translated by Arthur Mendel) includes an account of Bach's acquaintance with Silbermann's pianos:

One of them was seen and played by the late Kapellmeister Johann Sebastian Bach. He had praised, indeed admired, its tone: but he had complained that it was too weak in the high register, and was too hard to play. This had been taken greatly amiss by Mr. Silbermann, who could not bear to have any fault found in his handiworks.

He was therefore angry at Mr. Bach for a long time. And yet his conscience told him Mr. Bach was not wrong. He therefore decided-greatly to his credit, be it said-to think all the harder about how to eliminate the faults Mr. Bach had ob served.... He worked for many years on this.... I myself heard it frankly acknowledged by Mr. Silbermann. Finally when Mr. Silbermann had really achieved many improvements, notably in respect to the action, ... he had the laudable ambition to show one of these instruments to the late Kapellmeister Bach and have it examined by him; and he received in turn complete approval from him.

Too much attention has been paid to Kapellmeister Bach's criticism of the piano and too little to the final sentences of this excerpt, in which it is so definitely stated that the Silbermann piano received his approval. Yet, not only is recognition of Bach's connection with the piano gradually impressing it self upon contemporary scholars, but more attention is being given to his connection with composing styles that extend well beyond the varied stages of the baroque. Besides discussing Bach's acting as a sales agent for the Silbermann piano, Dr. Wolff establishes from external and internal structural evidence that the keyboard part of the Musical Offering was conceived and originally composed not for the harpsichord, but for the piano. In the July 1976 issue of the Musical Quarterly, Dr. Robert Marshall of the University of Chicago presented some convincing material about Bach's adoption of the more advanced keyboard composing styles, as evidenced in the Goldberg Variations.

From my studies of original written sources and Bach's structural styles, I have always been fully convinced that he understood sonorities of every type, including the piano, and that his branching out in composing styles embraced not only those considered advanced in his time, but clearly further into the future. The G sharp minor and B mi nor Preludes of The Well-Tempered Clavier (Book II) are closer in style to Mendelssohn's piano writing than to any facet of the "baroque." Arnold Schoenberg once told me that "Bach was the first twelve-tone composer," referring to the B minor Fugue of Book I.

Reproduction of antique instruments in the twentieth century has been very beneficial in increasing our knowledge of historical performance practices. It has also contributed greater insight into the type of sonorities native to the keyboard instruments, strings, winds, and brass of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The increasingly refined art of recording has been of inestimable value in bringing performance on these instruments to the international public. But while these areas of activity must continue to spread in sight into the world of antique sound, they have fostered a habit of thinking that specific instruments and their sonorities are indispensable to the reproduction of a musical style. Although this focus is regarded by many as an absolute standard, it represents a contemporary and not an eighteenth-century attitude. I find it amusing that while today's "sophisticated" concertgoer may look a skance at Bach played on the piano, he accepts with enthusiasm the same music played on a Moog synthesizer. (I have joyfully performed Bach on electronic instruments myself. But when I do, I do not go electronically haywire, but perform with the original structures and textures in mind.) Bach's own works show that he did not think in terms of stamping an exclusive sonority upon his music. Substitution of instruments was a standard practice in his day. The study of his cantatas, of the orchestral or solo concertos, and even of the solo instrumental works demonstrate irrefutably that Bach's flexibility in envisioning and performing the same music with widely differing instrumental timbres and textures was virtually limit-less. Norman Carrell has enumerated in great detail the many and varied types of instrumental, vocal, and choral transfers in his admirable book Bach, the Borrower.

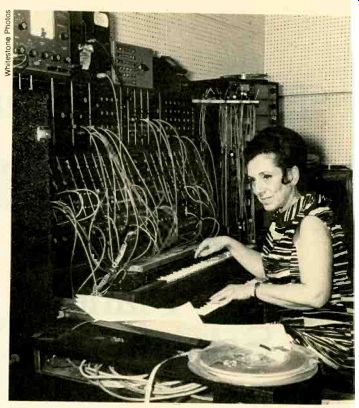

----------- Before a concert at the Library for the Performing Arts

at Lincoln Center, the author, obviously relishing the prospect, poses

at a Moog synthesizer upon which she is to play Bach.

Among the hundreds of such examples is the famous D minor Clavier Concerto. Its first and second movements appear in the first two movements of Cantata No. 146, "Wir mussen durch viel Triib sal," with a solo keyboard setting for the organ.

The first movement is virtually identical in both works. The solo part in the second movement of both is also unchanged, except for a few minor variants of embellishment, but in the cantata Bach superimposes a four-part choral setting over the organ part. This addition does not alter his treatment of the solo material for the organ despite the fact that the cantata movement's over-all sonority, texture, volume, and tonal balance with the orchestra, organ, and chorus is entirely different from that of the concerto with solo harpsichord and orchestra. We are quite sure that a setting for solo violin was made, though no manuscript is extant, and we cannot know for which instrument the original was composed; but any violinist can spot extensive sections of passagework in the outer movements that utilize the violinistic technique of alternating stopped notes with the open E, A, and D strings. A violin version again presents a totally different set of solo and interacting sonorities, textures, and general tonal balance. No more greatly differing techniques and their aural results can be conceived than those of organ, violin, and harpsichord. Does this frequent practice of Bach's bespeak the intention on his part to as sign to a composition the sonority and texture of a single instrument? If the realization of his intentions were so confined, he would not have continually set fresh versions in opposing sonority groupings.

It is equally revealing to consider the most famous of Bach's collections for solo instrument The Well-Tempered Clavier. For well over a century this title was wrongly translated into English as The Well-Tempered Clavichord. For a long time the error produced the impression in the minds of teachers and performers that the forty eight preludes and fugues were conceived specifically for the clavichord and that they should be played in imitation of its intimate style. Unfortunately too little was known about the true nature of the clavichord's touch and subtle tonal qualities. The result was frequently a drearily simplistic performance style of very complex music. Alternatives ranged from varying degrees of Romantic pianistic approaches to pedantically dry and stiff performance. In more recent times it has been fashionable to think that the "clavier" in the title means the harpsichord. "Clavier" is a generic term, which simply means "keyboard." In Bach's era interchanging clavichord and harpsichord was commonplace-and still was in Mozart's time. Mozart himself performed on either the harpsichord or the piano, but he was the last major composer and performer to do so. Musicians of his period were already imprisoning themselves in single minded instrumental approaches to both composition and performance.

One of the chief concerns of the nineteenth century was the development of color and timbre in association with musical structure. When a com poser conceives motives of a work in colors and timbres and his entire structural organization is built within these color relationships, the musical mind-whether of composer, performer, or in formed listener-loses the capacity to separate the colors from the motives and organization. The contemporary composing mind tends to base its motivic structures and musical organization al most entirely on color, timbre, and their rhythmic combinations. It is difficult-perhaps impossible for many musicians to dissociate structure from color. But this association is one upon which Bach was not dependent.

We tend today to insist too narrowly on the use of the harpsichord for all of Bach's keyboard mu sic. The clavichord has been greatly neglected chiefly because it is a most impractical instrument for use in the current ambience of public performance. Our concert halls are too large for its fragile tone to be heard. Recording has brought harpsichord tone successfully to everyone's ears, but the clavichord still presents problems. Another difficulty is the nature of clavichord tone production:

The instrument requires vibrato touch. Modern performers too often eschew this indispensable type of touch, or they exhibit too little skill in the subtleties of finger and hand vibrato. On the clavichord gradations of tone are not only possible, but required within single notes as well as phrases.

Thus the entire style of playing Bach is altered, when performed on the clavichord, to one of acute sensitivity to every nuance and degree of tonal quality. The harpsichord is mechanically regulated in its changes of color and texture. A skilled harpsichordist can make some fine differentiations with the fingers, but essentially the instrument is dependent for its differentiation of volume and quality on mechanical means, either by transfer of the hands from one keyboard to another or by the use of registration. The organ is similar in this respect. The clavichord alone is wholly receptive to and dependent on the fingers' touch. And it is unarguable that the clavichord is very closely related to the eighteenth-century piano.

On the subject of the interchangeability of key board instruments, C.P.E. Bach says in his Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments:

"Every keyboardist should own a good harpsichord and a good clavichord to enable him to play all things interchangeably. A good clavichordist makes an accomplished harpsichordist, but not the reverse." His comment on clavichord touch also applies to piano touch: "Those who concentrate on the harpsichord grow accustomed to playing in only one color and the varied touch which the competent clavichordist brings to the harpsichord re mains hidden from them." Thus it is clear that musicians expected variety of touch and dynamics, regarding them as the most desirable devices of performance style. This variety is the keystone of pianism. I cannot forget the misguided comment made by one member of the audience after a piano recital of Bach: "Isn't it wonderful how he can play for almost two hours and make it all sound the same!" The great fault lies, then, not with the instrument itself, but with the musical attitudes, techniques, and aesthetic vision of performers. I have heard un-stylistic performance on clavichords and harpsichords as well as on pianos. The solution to authentic performance lies not in the medium employed, but in the totality of deeper factors. The fulfillment of Bach's intentions must be the product of the individual's historical knowledge and instrumental skills combined with an artistic achievement that derives from psychological identification with Bach's musical orientation.

==============

(High Fidelity, Oct. 1977)

Also see:

The New Releases--A Window on Lully's Operatic World; Heinz Holliger: Now That's Charisma