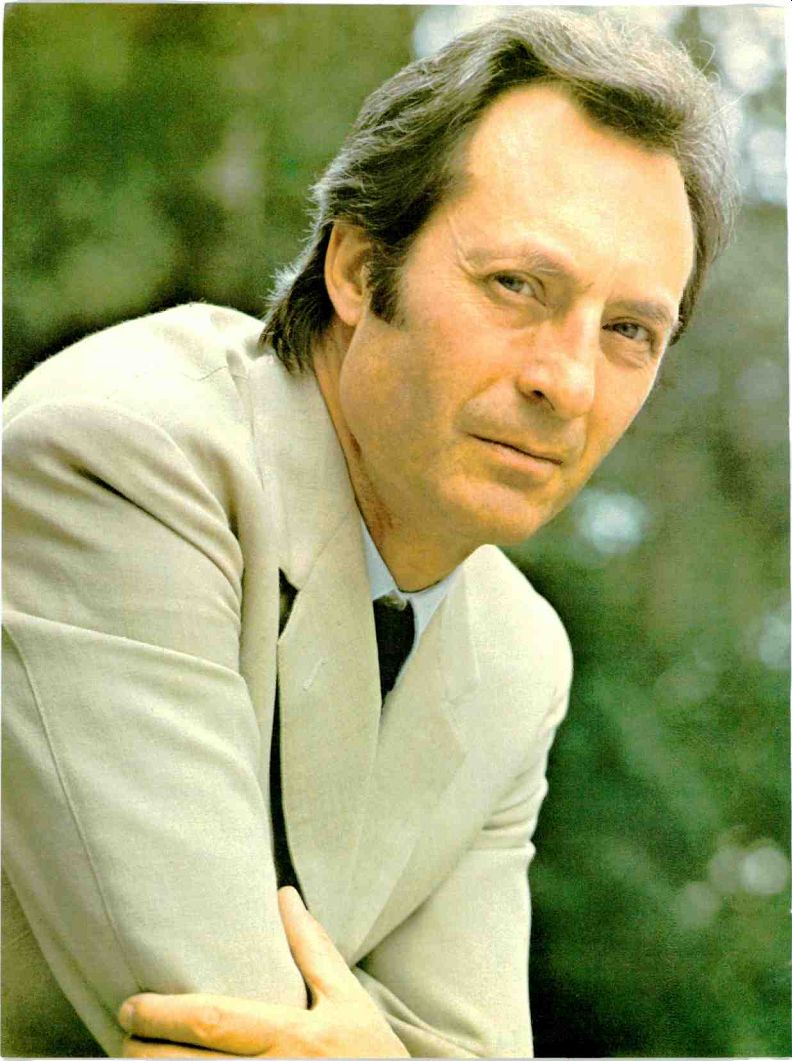

CONDUCTOR CARLO MARIA GIULINI--"The orchestra is not an instrument! It is human beings who play instruments"

"... more and more I find orchestras everywhere can do everything."

By Roy Hemming

AMONG today's major symphony and opera conductors, Carlo Maria Giulini cuts an especially imposing figure. Tall, classically handsome, and with a full head of greying but still predominantly dark hair, he looks much, much younger than his sixty years-an age to which he admits with disarming direct ness. His manner, both on and off the podium. is suave and elegant in an Old World, always gentlemanly way. Other musicians I've interviewed go out of their way to speak of him as one of the most gracious and charming colleagues they've ever worked with. "I adore Giulini," Alexis Weissenberg told me. "Giulini is absolutely marvelous," says Shirley Verrett. Other comments from fellow musicians inevitably end up sounding like a fan-club oration.

Yet Giulini remains something of an enigma on the contemporary music scene. He is as concerned with maintaining a cultivated balance in his personal life as he is with being a world-famous conductor. In an age when most musicians jet here, there, and everywhere week after week, Giulini rigidly restricts the number of engagements he will accept. He shuns big social events and as much of the publicity whirl as he possibly can. When he is not conducting he flees to the privacy of his small-town home in the mountainous region of northern Italy.

Until last year Giulini had steadfastly turned down offers to head major orchestras in both the United States and Europe. The closest he had come was his engagement, dating from 1969, as principal guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Other than that, he had long insisted that he did not want to get tied down to a permanent post with any orchestra. Then, to almost everyone's surprise, Giulini agreed last year to become music director of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra.

How had Vienna gotten him to change his mind? Giulini smiled as he replied to the question during a recent interview in New York. "You see, the title 'music director' is a bit different there than here. It is more like chief conductor.

This is all I really am in Vienna. I am not at all interested in administration. I put this to them very clearly. I want nothing to do with such problems-only with musical problems. For example, if they want me to hear an audition. I do so. Just so it deals with music.

"Another condition I made," he continues in soft-spoken, lightly accented English, "is that I don't want to conduct I find orchestras everywhere very often. Perhaps five or six programs in all the year. Of course, if and when the orchestra goes on tour outside Vienna, I will tour with them as their chief." Does his Vienna contract give him approval of other conductors and pro grams when he's not there? "Yes," he replies, "although arranging everything is a little bit complicated because I prefer not to live in Vienna." Home for Giulini is Bolzano, in the Dolomite Alps, not far from the Austrian border in northeastern Italy. "When I am not conducting I stay there expressly to be quiet, to be in contact with nature." He makes the comment without any of the pretentiousness or 'affectation it might bear coming from another speaker.

"My home used to be in Rome, then Milan, but I don't want to live in big cities any more," he explains. "Cities, I feel, are less and less for human beings.

When I conduct, of course, I am obliged to be in the big cities, because that is where the great orchestras are. But after the concerts I must get away. This is very important to me."

ALTHOUGH Giulini was born in the Adriatic town of Barletta in southern Italy, he grew up in the Dolomites. His father was a lumberman whose work frequently took him into the forests of neighboring Austria. In the peace settlement that ended World War I in 1918, Italy's northern border was extended to include territory that had formerly been Austrian. That's when Giulini's father moved his family to a small town in the newly Italian territory that he had known and liked before the war.

"It was a beautiful town, surrounded by forests," Giulini says, illustrating the comment expressively with his hands.

"We were one of the first Italian families there, so I grew up speaking both German and Italian. I started kindergarten there, and also my first music lessons.

"I think I was about four years old when I first saw a violin. You know the man who goes about the village playing the violin for charity-what is he called in English? Well, never mind. I must have been very taken with his playing, for when my father asked me what I wanted for Christmas I said a violin. So he bought me a starter-size violin. My mother told me later that I was absolutely crazy about learning how to play it and to play everything! "I began taking lessons from an old Bohemian violin master who lived in the village. I will never forget that man. I studied with him until I was twelve.

Then the Italian government set up a new music school in the region under a cousin of the composer Mascagni. He sent a young Italian violinist to our town with a whole new conception of teaching. My Bohemian teacher, who loved me like a son, said to me:

'I am old. Go and start fresh with this new teacher.' How he must have suffered as he said it--but he understood."

When Giulini was fifteen his family realized that their town was too small for further important musical study. So they packed him off to Rome. At the Santa Cecilia Conservatory he studied violin, viola, and composition. By the mid-Thirties he was already playing in a string quartet.

"Each summer I always went back to the mountains. One of my teachers sent me a telegram there, telling of a competition for the last viola chair in the Augusteo Orchestra in Rome. At that time the Augusteo was a really great orchestra.

So I went back to Rome to enter this competition. When they told me I was the winner of the twelfth seat in the viola section, this was for me the greatest joy of my musical life- before or since! "And what an experience it was. We played under all the greatest conductors--Mengelberg, Kleiber, Klemperer, De Sabata, Richard Strauss, Bruno Walter. Sometimes we would play the same Brahms or Beethoven symphony with Walter and De Sabata-two completely different conceptions, and both great conceptions. When you sit there and play with such great musicians-even when you are in the last chair--you can not help but get excited." Giulini's love affair with orchestras has lasted ever since, although it has been from the conductor's podium rather than as a player since the end of World War II. It was Giulini who led the first concert at Rome's Teatro Adriana following the liberation-after he had spent months in hiding from the Nazi police as an anti-Fascist. In 1946 he became a conductor for Radio Italiana, and in 1953 a principal conductor at Milan's La Scala Opera. His American debut came in 1955, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

During the 1950's and 1960's, Giulini was most closely identified with opera.

In those years he was the conductor for some of the great Angel recordings with Maria Callas and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, and he was principal conductor for the Rome Opera's visit to the United States in 1968. Then, amid reports that he was increasingly dissatisfied with the casts he had to work with and with production problems at major houses, he announced in 1969 that he was giving up opera to concentrate on symphonic music--at least for four or five years.

Since that length of time has now elapsed, is he thinking of going back to opera? Giulini answers quietly but firmly: "I have no projects for the opera house. I have no time now for opera, because there are so many symphonic works I haven't performed that I would still like to do. And I really don't want to conduct too much. I don't want to get used to the music I perform. For me, every performance, every rehearsal must be a great event. I do not want it to become routine. That possibility terrifies me.

"I am afraid, I know that I'm afraid, and I know also why I'm afraid. This mystery of music--the mystery of sound that before you actually hear it you first hear it inside yourself- you cannot let this become like a machine. So I perform for three or four weeks, and then I must have three or four weeks to myself-- to study, to think, and to re-study. I find that the more years I live and the more experience I acquire, I must study again and again to try to understand the creative geniuses for whom I would be a servant.

You cannot jet everywhere all year long and do this." Just as he fights the increasingly machine-like "manufacture" of music today, Giulini bridles at impersonal references to an orchestra as an instrument.

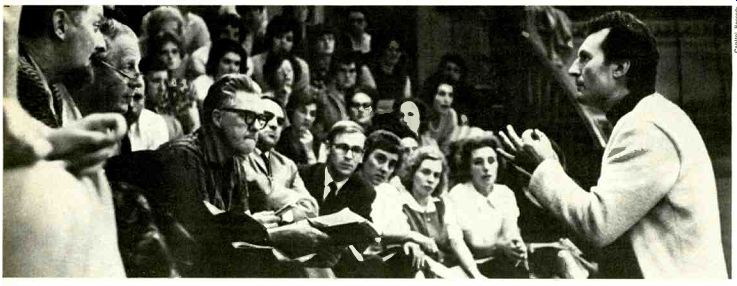

"I hate this," he says. "The orchestra is not an instrument. It is human beings who play instruments. That's a very different thing!" Can orchestra players then, I asked, shape the way a conductor will play a particular work? For example, will Giulini himself play the Brahms First Sym phony differently with the New York Philharmonic than he will with an orchestra in Rome or London because the individual players are different? "Every great orchestra has its own character, its own personality," he replies. "The conductor must understand what that character is, and then try to bring out his sound, his conception. A work that is played in London may sound different because of the character of the orchestra, but the artistic conception, the interpretation of the conductor will be his wherever he conducts." How about a Mahler or Bruckner symphony played by an orchestra in Vienna which has grown up with a certain tradition or identity with these com posers? "Yes, in Vienna there are some charming things that it is impossible for others to imitate," Giulini admits. "It's been with them for so many years. But music is much more than this. And more and more I find orchestras everywhere can do everything. There are no longer borders. I do not believe in borders.

Human beings, I feel, are much the same everywhere. We all have a heart. Some times the outward expression of individual feeling is different. But what is inside us is fundamentally the same--the sorrow, the joy, the tears, the smiles, all these things.

"Sometimes I hear it said in Europe that American orchestras are splendid but cold. I get a bit crazy whenever I hear this. It is not true! Sometimes an American orchestra can play cold, just as a European orchestra can play cold. It is up to the conductor to bring out its heart." There are many who would agree that Carlo Maria Giulini has few peers today in being able to do just that. Maybe it's his ability to pull back from the rush of the modern world that has made it possible for him not only to preserve his own contact with the music that is so important to him, but to serve so well as one of ours.

==============

Also see:

THE EAGLES -- "As far as we're concerned, the bottom line is the songs"