TURNTABLE BASICS: A little preliminary homework will make you a lot smarter in the market

Julian Hirsch focuses on TURNTABLE BASICS for the component shopper

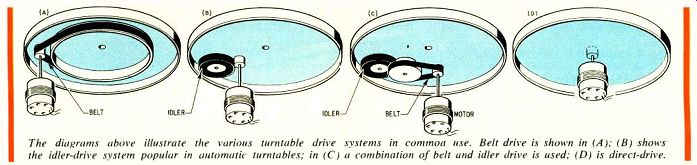

The diagrams above illustrate the various turntable drive systems in common use. Belt drive is shown in (A); (B) shows the idler-drive system popular in automatic turntables; in (C) a combination of belt and idler drive is used; (D) is direct-drive.

GLOSSARY: RECORD-PLAYER TERMS

Acoustic Feedback: In some installations, or rooms, sound (traveling through the air or by way of the floor or cabinet) may vibrate the record player in such a way that the cartridge will generate an output voltage. The result is called acoustic feedback, which is heard as a loud rumble or howling sound, particularly when the speakers have good bass response and are played at a high level.

Even before it reaches the distress level, acoustic feedback can muddy the sound.

Good installation practice requires that the record player be isolated from the speakers to the greatest possible ex tent. However, record players differ widely in their ability to resist external vibration. Some are mounted on highly compliant "feet" that isolate the entire unit from the shelf or other support.

Others depend on springs or similar isolators between the turntable mounting board and the player's base. Frequently the arm and platter bearing are mounted as a subassembly on a rigid frame or plate, and the combined structure is suspended from the mounting board (this helps to prevent the movement of one relative to the other).

Flutter: A rapid pitch fluctuation in reproduced music, caused by pulsations of the turntable speed. Flutter occurring at a low rate is called "wow," from the characteristic sound it imparts to steady musical tones. At higher rates, the effect is of a "gargling" or roughness. Wow and flutter are often combined into a single flutter measurement, which may be weighted to emphasize the most objectionable flutter rates (around 5 to 10 Hz).

Rumble: A low-pitched sound, caused by mechanical vibration acting on the turntable and tone arm. This vibration may occur at the rotation frequency of the motor, the idler, the platter, or multiples of any of these frequencies. Rumble often sounds like power-line hum, but it disappears when the pickup is lifted from the record. Weight ed rumble measurements discriminate against subsonic frequency components, which cannot be reproduced by loud speakers or heard by the human ear. However, such frequencies can over drive an amplifier or speaker and impair the reproduction of higher frequencies, so that an unweighted measurement is also informative.

Servo Control: A technique by which the output of a device is compared with the input signal or with a reference quantity, and the difference between the two is used to force the output into conformance with the input or reference signal.

In the case of a turntable, the reference may be a precisely regulated voltage and the output feedback signal a variable voltage proportional to the turntable speed. Any difference between the two voltages varies the driving signal to the motor (and thus its speed) until they are nearly equal, thus maintaining constant turntable speed under conditions of varying line voltage or record load.

A servo-controlled tone arm senses any departure of the arm from tangency with the record groove. Such a departure causes the arm to move in such a way as to restore tangency.

Skating Force. When a cartridge is mounted at an offset angle in a pivoted tone arm, friction between the stylus and the record material creates a force component directed toward the center of the record. This effectively adds to the tracking force on the inner groove wall (left channel) and subtracts from the force on the outer (right channel) groove wall of the record. If the cartridge is being operated near its minimum tracking-force limit, this can cause mistracking and distortion on the right-channel program. As an alternative to increasing the total vertical force (which may exceed the maximum rated force for the cartridge or result in excessive tracking force on the inner groove wall), an equal and opposite force can be applied to the pickup through an anti-skating system.

There is no agreement as to the "correct" amount of anti-skating compensation. A small amount will keep the pick up from moving inward when it is placed on a rotating un-grooved record. How ever, the friction in a record groove is higher, so that more force is needed to equalize the wear on the two walls of the groove and on the stylus. Still more force is needed to provide equal tracking ability in both channels at high recorded velocities. But as long as the anti-skating compensation is not excessive, thus producing a net outward force, any amount is beneficial.

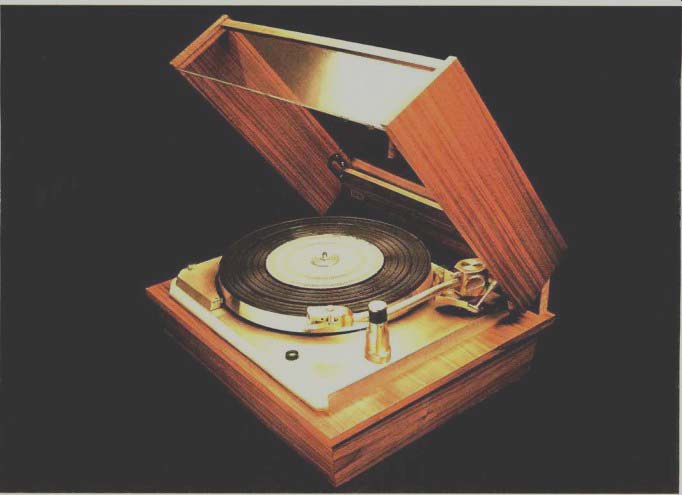

SHOPPERS in today's hi-fi component market are fortunate in having a huge assortment of record players from which to choose, and the intense competition between the various manufacturers has made it possible for the consumer to get the maximum value for his investment. On the other hand, making a choice from among the many available units, even within a limited price range, can be a formidable task. It will be simplified considerably, however, if the buyer has prepared himself with an understanding of the basic record-player design approaches and features.

To begin with, the typical record player is usually sold as a coordinated combi nation of a turntable and tone arm in stalled on a base. Some models are also supplied with a suitable cartridge mount ed and properly positioned, but these are still in a minority.

Modern high-quality record players are almost equally divided between single-play and multiple-play types. The multiple-play machines used to be known as record changers or automatic turntables. Changers are all "automatic" in the sense that the user does not have to handle the tone arm, but most single-play units also have some degree of automation. In its simplest form, this may be nothing more than an end-of-record arm lift, perhaps with a simultaneous motor shut-off, but the trend seems to be to ward fully automatic operation, equivalent to that of a record changer, except that the record doesn't change.

Almost every record changer also has a manual mode and a short, stubby shaft to replace the "umbrella" or angled spindle commonly used to support a stack of records and drop them in sequence. This versatility does not come without cost.

At a given selling price, it is almost certain that a single-play unit will be superior in some aspect of its construction or performance to a multiple-play changer (though this superiority will not necessarily be in an audible area). Conversely, while there are record changers whose quality matches or surpasses that of many single-play models, they are usually quite expensive. The message is plain: if you do not really need a record changer, you can either save money or get a "better" product for the same money in a single-play turntable.

Since the turntable and tone arm are functionally separate, it is perfectly possible for a superior turntable to be paired with an unexceptional tone arm, or vice versa. This usually makes it difficult to state with confidence that player A is better than player B, except when both of its components are plainly superior.

Turntable Drive Systems

In the better turntables, the platter on which the record rests is machined alloy so that it will not attract the magnet present in most phono cartridges. Platter weight may be anything from less than 2 pounds to as much as 9 pounds, and the heavier platters are often touted by their manufacturers as providing superior performance. This is not necessarily true, since mass is by no means the only-or even the most important--requirement for state-of-the-art turntable performance.

Several types of turntable drive systems are commonly used, each having its pros and cons. Potentially, the least expensive (and therefore the most widely used in the lower price ranges) is the idler drive, usually in conjunction with a four-pole induction motor turning at about 1,800 revolutions per minute (rpm). The rubber idler wheel, which serves to "gear down" the motor-shaft speed to the 33 1/3 or 45 rpm of the platter, contacts both platter and motor shaft directly. Unfortunately, this tight mechanical coupling can transmit to the platter and record whatever vibrations and speed fluctuations there are in the motor. For this reason the better idler-

drive machines use very well made, specially designed motors that are relatively vibration free and whose speed is completely unaffected by a.c. line voltage changes. In this higher price range ($130 and up) rumble and flutter are likely to be lower than in the less expensive players driven by simple and more cheaply made induction motors. Paradoxically (since they are least likely to need it), the players with true constant-speed motors often have vernier speed adjustments that let the user vary the speed a few percent above and below the nominal value.

In general, a belt drive is mechanically simpler and transmits less flutter and rumble to the platter than an idler-drive system (although there are exceptions to this); most single-play turntables use belt drive. Usually the belt is driven by a synchronous motor turning at a speed in the 300- to 600-rpm range. This places the basic vibration (rumble) frequencies be low audible limits (5 to 10 Hz). A disadvantage of the belt system is that it transmits a limited torque to the platter, and this may prevent it from operating conventional record-changing mechanisms. However, several manufacturers have recently succeeded in developing sophisticated belt-driven record changers.

The most sophisticated drive system is direct drive, in which a special low speed motor rotates the platter directly at the playing speed. Direct-drive turn tables can have nearly ideal characteristics, but they may be costly. Only one direct-drive record changer has been manufactured, and it is considerably more expensive than the best of the conventional-drive changers. All the direct-drive turntables (and some of the best belt-driven units) use a servo system to maintain their speed at a constant value and to reduce flutter to an almost unmeasurable level.

Rather than becoming involved in mechanical details, the buyer should remember that competition is keen in the record-player field and for that reason overall quality is usually directly reflected in selling price. Each manufacturer has therefore chosen the drive system-or systems-that will, in his judgment. provide the best performance in a given price range. Of course, price does not correlate 100 percent with quality, but it is certainly an excellent reference point from which to start-at least when dealing with turntables.

Turntable Features

Performance aside, what features should you look for in a turntable? Al most every modern record player operates at both 33 1/3 and 45 rpm, and this reflects the facts of record production. However, the nature of the repertoire on 45's and the inconvenience of playing them singly would probably make a record changer fitted with a large-diameter automatic spindle the best choice for playing them. In addition, since the special calibration/test discs supplied with most CD-4 components also operate at 45 rpm, it is desirable to have that speed available even on a single-play turntable if you are gearing up for four-channel. If you decide on a record changer, you will want to consider the maxi mum number of records you will likely play automatically at any one time. Cur rent models can handle stacks of four to ten 12-inch long-playing records, with six being the most common number.

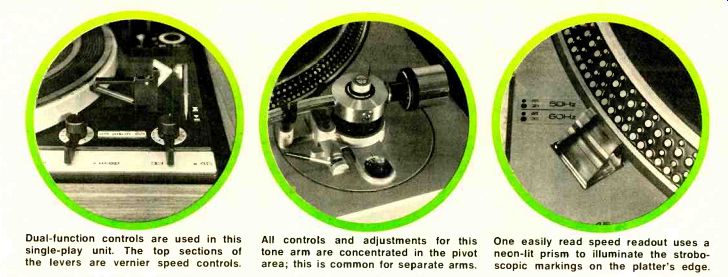

A turntable with vernier controls for fine adjustment of speed should have illuminated stroboscope markings located so that they can be viewed while a record is being played. Some models have the stroboscope markings at the center of the platter, where they are not visible when a record is in place. This is less desirable, except when the unit is servo driven so that its speed is not affected by the drag of the stylus in the grooves of the record.

Most record changers and semi-automatic single-play turntables have a control that must be set to index the arm for the required record diameter. If you play only 12-inch LP's this is of little consequence, but if you have appreciable numbers of 10- or 7-inch discs, you may wish to consider one of the few players that choose the proper index point automatically. A couple of deluxe single-play turntables are completely automatic, selecting the correct operating speed and indexing diameter without any action on the part of the user. Although they are expensive, their overall performance is correspondingly high.

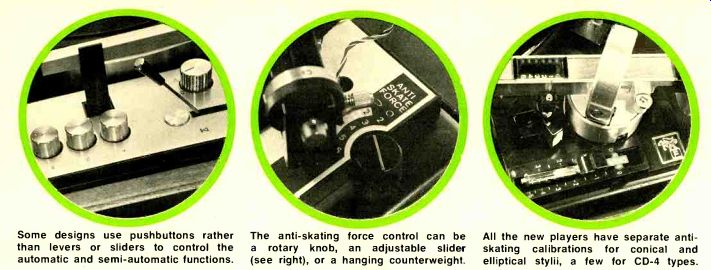

----------- Some designs use pushbuttons rather than levers or sliders

to control the automatic and semi-automatic functions. The anti-skating force

control can be a rotary knob, an adjustable slider (see right), or a hanging

counterweight. All the new players have separate anti-skating calibrations

for conical and elliptical stylu, a few for CD-4 types.

Tone Arms

Although tone arms come in a variety of shapes, almost all are basically metal tubes, pivoted near one end on low-friction bearings, and supporting the phono cartridge at the other end. The different tone-arm configurations ("S" bends and the like) derive from the requirement (for proper tracking) that the cartridge be offset at an angle to the line joining its stylus to the horizontal pivot. Any well-designed arm can play a record with negligible tracking error if the phono cartridge has been installed correctly.

A counterweight at the rear of the arm balances the mass of the cartridge and forward portion of the arm, and the necessary vertical tracking force is applied by a slight readjustment of the weight or by a spring. Usually a calibrated scale shows the force in grams. These scales differ somewhat in convenience and accuracy, but almost all are sufficiently accurate for their purpose. Lower-price record changers sometimes lack calibrated force scales and tracking force must be set up with a separate gauge.

Every offset tone arm is subject to a skating force that tends to swing the pickup in toward the record center. This can cause uneven record and stylus wear, and sometimes distortion in one channel when playing heavily recorded passages. Practically every record-player arm has some form of anti-skating compensation using springs, magnets, levers, or hanging weights. The several systems differ in their effectiveness and accuracy, but since the amount of compensation required with any player or record can only be approximated at best, most of them are quite satisfactory.

Every arm should have some device that allows the pickup to be lifted from the record automatically by moving a lever or pressing a button and then (ideally) returned to the same groove area. On most of the better record players, the arm lift is damped, providing a slow, gentle rise and fall that does not jar and shift the pickup, even if it is done rapidly. Some arms are pulled outward during their descent by the anti-skating force. This can negate much of the usefulness of a cueing lift, so check its accuracy before buying.

Some low-price record changers do not permit completely free arm movement, and may apply undesirably high forces to the stylus when the mechanism that raises the arm at the end of a record operates. Fortunately, good players are virtually free of such effects and can be used safely with the highly compliant and delicate styli in today's cartridges. An important feature is the quality of the tone arm's bearings, which vary from simple point-in-cup pivots to precision ball bearings or knife edges. The record player manufacturer will usually rate his arm for use with cartridges operating above a certain minimum tracking force, and it is wise to stay within these limits (and to keep well above the lower limit, if possible). The particular pivot principles used is not important; how well it works is.

On any record changer, the angle be tween the arm (and cartridge) and the record changes as the record stack on the platter grows higher. Theoretically this could slightly increase the distortion by altering the vertical tracking angle of the cartridge, but a more serious problem is the possibility of the cartridge body's touching the record when playing the last record of a stack. Two slightly different steps have been taken by record-changer manufacturers to correct this condition at least partially. In one the cartridge holder is tilted in the vertical plane by means of a knob or lever so that it remains parallel to either a single record or to a record at the center of the maximum stack height. Another system raises the entire tone arm to achieve the same result. Both systems are equally effective. Needless to say, this problem does not exist with single-play units.

There are a couple of radial-tracking tone arms (integrated with high-quality turntables) that move in a straight-line path across the record and are free of the tracking-error, vertical-angle, skating, and mass problems of other arms (a radial arm is always tangent to the groove and has no tracking error or skating force). These arms are servo-driven, and the players using them are expensive.

---------------

TEST RECORD

THE Stereo Review Model SR 12 Stereo Test Record has specially recorded bands for evaluating rumble, wow, and flutter without test instruments. It is a worthwhile investment, not only for testing a turntable in the showroom, but also because it permits you to check cartridge tracking with different stylus-force settings and accurately set a tone arm's anti-skating adjustment. Full instructions for using the SR 12 are supplied with the record, which is available from Ziff-Davis Service Division, 595 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10012: $5.98 postpaid within the U.S.; $8.00 outside the U.S.

------ Dual-function controls are used in this single-play unit.

The top sections of the levers are vernier speed controls. All controls and

adjustments for this tone arm are concentrated in the pivot area; this is

common for separate arms. One easily read speed readout uses a neon-lit prism

to illuminate the stroboscopic markings on the platter's edge.

Performance

The performance specifications of two record players can be compared only if they were measured in the same manner; unfortunately, there is so far little standardization of test methods within the industry. Valid comparisons can be made between different record players when tested by the same laboratory (as in the Hirsch-Houck Laboratories re ports in STEREO REVIEW), or between different models from the same manufacturer. However, one cannot assume that a turntable from company A, advertised as having 5 dB less rumble than one from company B, is actually lower in rumble.

It could even be higher! Rumble is expressed as a number of decibels (dB) below some reference re corded velocity level. Often the reference velocity is unspecified, but most common values fall within a few decibels of each other. However, most manufacturers use a weighted measurement, sometimes without specifying the weighting curve. (Weighting minimizes the low-frequency noise contribution on the basis that it is less likely to be heard).

It is not unusual for a weighted measurement to be as much as 30 dB lower (better) than an unweighted measurement, so be sure you are not comparing "apples and oranges"-different kinds of weighted or weighted and unweighted figures, that is-when judging turntable specifications.

Wow and flutter are different audible manifestations of the same problem-a rapid and periodic speed fluctuation of the turntable. At low fluctuation rates, the "wow" imparted to the sound is unmistakable, but at high rates the flutter effect may be no more than a barely detectable "muddying" of the sound. Usually the two are combined in a single flutter measurement, which may be peak or rms (root mean square), weighted or unweighted (Hirsch-Houck Labs measurements are unweighted rms). Unweighted flutter readings are always higher than weighted readings, so be careful when comparing these published figures as well.

Individuals differ in their ability to perceive flutter, but it is safe to assume that a turntable with less than 0.1 percent unweighted flutter (many are this good or better) will not introduce audible flutter. At 0.2 percent, critical listeners will usually hear flutter on some program material, and the 0.3 percent or greater flutter of some low-price record players is unacceptable for music listening.

Most tone-arm specifications mean little by themselves, since ultimate arm performance depends on the cartridge used in it also. In a way this is just as well, since almost no quantitative data, other than physical dimensions, are published by most tone-arm manufacturers.

The aspects of tone-arm performance that will be of most concern to the user are the "handling" characteristics smoothness of operation of the cueing device, the shape of the finger lift, and so forth.

Rarely will a record-player manufacturer refer to his product's immunity to acoustic feedback. Many otherwise satisfactory players cannot be used in proximity to speakers having a strong low bass output, except at reduced listening levels, without annoying and potentially destructive (to the speakers) acoustic feedback. On the other hand, some record players are nearly immune to feed back. Test reports provide some guidance in this matter, and the advice of a reliable dealer can be very helpful.

Other Factors

There are a number of factors not covered by most specifications that can influence the performance or convenience of use of a record player. In the case of a record changer, the ability of its dropping mechanism to function with records having slightly out-of-tolerance center holes or thicknesses is obviously important, though quite difficult to as sess. If you have some records that have been troublesome on another changer, take them to the dealer's showroom and try them on any model you are considering buying.

Some early record changers earned a reputation for rough handling of records and cartridges. Today's models even the inexpensive ones-are at least as gentle as the hand of a skilled human operator, and some are considerably better than that. In fact, one is less likely to damage a valued record or cartridge with a good modern changer than with a manual record player.

Unless the record-player manufacturer specifically states that his tone-arm wiring capacitance is low enough for use with a CD-4 quadraphonic cartridge, you can assume that it is not. Unfortunately, some players are claimed to be "CD-4 compatible" but still require a different kind of cable between the record player and the demodulator to achieve the necessary low capacitance.

If CD-4 is a part of your present or future plans, be sure to check this point, since it may not be practical to rewire a tone arm at a later date.

Checks You Can Make Yourself

Many of the operating characteristics of a record player, such as the number of speeds, the various controls and their functions, the handling ease of the tone arm, and the convenience of the control layout, can be checked easily in the dealer's showroom. But it is also a good idea to take along your worst records--those pressed off-center, warped, or with non standard center holes--to evaluate the player's ability to cope with less-than-ideal conditions. If possible, make these checks with the same cartridge you plan to use or at least one with similar tracking-force requirements. Some performance characteristics, such as wow, flutter, rumble, and anti-skating compensation, can be checked roughly with the aid of the STEREO REVIEW SR 12 test record (see accompanying box for instructions on how to order).

---

also see: TECHNICAL TALK, JULIAN D. HIRSCH