"A good singer is born with a voice, but he must learn how to work with

it".

by WILLIAM LIVINGSTONE

MANY things go into building the career of a young musician talent, training, ambition, and luck. According to the Belgian bass-baritone Jose van Dam, "The best thing that can happen to a young singer is to have an important conductor take an interest in his or her career." Several conductors have been instrumental in Van Dam's career. "The first was Lorin Maazel," he says. "I was little more than twenty and was singing small roles at the Paris Opera, including some very small ones, like one of the soldiers in La Boheme. I auditioned for Maazel, and he asked me to record Ravel's L'Heure Espagnole with him.

That was the first step in my international career." Other conductors who have appreciated Van Dam's voice and musicianship and have engaged him of ten include Herbert von Karajan, Sir Georg Solti, and James Levine.

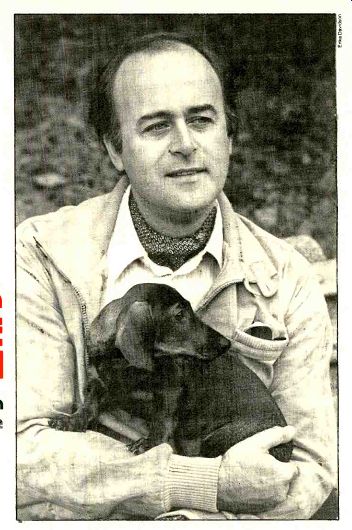

The traits that make Van Dam one of the finest singing actors of the day are of course discernible to audiences and critics as well as to conductors. When he made his Met debut as Escamillo in Carmen in 1975, John Rockwell of the New York Times referred to him as "the leading exponent of the role in the world today." When Van Dam returned to the Met in the 1977-1978 season, he received similar raves for his Colline in La Boheme, and all stops were pulled out for descriptions of his Golaud. Andrew Porter in the New Yorker wrote that the Met's revival of Pelleas et Melisande was "distinguished by a Golaud, Jose van Dam, of rare excellence-one who combined warmth and strength of tone, impeccably clear words, and force of dramatic personality." interviewed Van Dam at a friend's apartment in New York where he was making a twelve-hour stopover be tween engagements on the West Coast and in Europe. He's a good-looking, appealing man of medium height and compact build, with a long expressive face and penetrating blue-grey eyes.

He wore black boots, black slacks, a tan sweater, and two watches, one set to local time and one to European time.

He was born on August 25, 1940, which means that he is a Virgo, a sun sign he shares with such other performing artists as Greta Garbo, Leonard Bernstein, Sophia Loren, and Maurice Chevalier. Amateur astrologers may be pleased to know that everything about him bespeaks the neatness, analytical turn of mind, precision, and devotion to work that are supposed to be typical of those born under this sign.

"I was born in Brussels and received my musical education there," he said.

"I gave my first concert in a children's festival when I was only eleven. I was not a boy soprano, but a contralto, and, after my voice changed, I did not be come a tenor as people expected, but retained the same tessitura. My voice grew deeper, of course, but as a child I went up to G, and that's my range now." Belgium has a distinguished operatic history and has produced many opera singers, among them Fernand Ansseau, Fanny Heldy, Rene Maison, and Rita Gorr. Despite this Belgian tradition, Van Dam is usually thought to be French. "Even in Paris the reviews refer to me as a French singer, perhaps because I made my debut in Paris, per haps because-my voice is that of a French bass. It is not the deep, black, German bass voice required for Sarastro in The Magic Flute or Baron Ochs in Der Rosenkavalier, but a bit higher, more a basso cantante. In Germany I am called a Heldenbariton, what you call in this country a bass-baritone. In Italy I would be a baritone because the orchestra pitch is lower there than in Vienna, for example.

"I think I am lucky to have a bass-baritone voice because it opens up to me many fascinating roles--Escamillo, Figaro, Don Giovanni, Leporello, Verdi's Attila, and Jokanaan in Salome.

Some of these are sung by baritones, but they are not really baritone roles." Escamillo has been a good-luck role for Van Dam. It was his debut role in Paris, La Scala, Santa Fe (where he sang his first American performances), San Francisco, Covent Garden, and the Met. Since he has sung it so many times in so many different productions, I asked him how he managed to keep it interesting. "You may sing a role a hundred and fifty times," he said, "but whenever you go out onto the stage, it's a first. The Met seats nearly four thousand people, and at a performance one or two hundred people may be hearing you for the second or third time, but the rest are hearing you for the first time. When it's the first time for the people, it's the first time for me too. Besides, singing is such a joy for me that keeping it interesting is not a problem." Van Dam has recorded Carmen in both the opera-comique version (with spoken dialogue) with Tatiana Troyanos, conducted by Solti ( London 13115) and in the grand opera version (with sung recitatives) with Regine Crespin, conducted by Alain Lombard (RCA/Erato 70900/2). Which does he prefer? "I think both are good on records," he said, "but in the theater especially a large theater-I prefer the version with the recitatives. They are nice although they were not written by Bizet [they were composed by the American-born Ernest Guiraud], and in the other version it slows the action every time the singers stop to speak.

Speaking is also very bad for the singing voice." He disagrees with the notion common among modern directors that Car men welcomes death and is a willing "I think a good singer is born with a voice, but he must learn how to work with it." collaborator in her murder by Don Jose. Do Carmen and Escamillo really love each other? "No. Escamillo is like Don Giovanni, a Casanova. And Carmen does not really love him. She is a woman like Frasquita or Mercedes.

For her, Escamillo is neither the first nor the last. Her duet with Escamillo in the last act is revealing. She says, 'Escamillo, je raime et que je meure si j'ai jamais aime quelqu'un autant que toi.' [Freely translated: 'I love you and may God strike me dead if I've ever loved anybody else so much.] Well, ten minutes later she's stretched out dead." AFTER his initial engagement at the Paris Opera, where he sang his first Escamillo, Van Dam won an important singing competition in Geneva and was invited by Herbert Graf to become a member of the company there. Two years later, Manuel, with whom he had made his first recording, invited him to join the Deutsche Oper in Berlin, another step in his international career.

"It is important to take these steps. It was not so difficult for me because I was very young and not married. Still, it takes courage to leave home and go to live and work in another country, but that is necessary in building a career." Now married and the father of a son, Van Dam makes his official home in Luxembourg. He is still a member of the Deutsche Oper and spends three months of the year in Berlin. The rest of a typical year, during which he may sing as many as sixty-five performances, is divided between Vienna, La Scala, the Met, the Paris Opera, and other major theaters.

THE next great conductor to take an interest in his career was Herbert von Karajan, who invited him to record the role of the minister Don Fernando in Fidelio in 1970, and he has since sung with Karajan frequently. Solti came into his life a bit later. In 1976, American audiences heard Van Dam with both of these conductors. He sang the title role in Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro under Solti when the Paris Op era made its official Bicentennial visit to the Kennedy Center and to the Metropolitan, and later that year he was a soloist with Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic in four straight evenings of choral works at Carnegie Hall. He has sung Figaro with both of these conductors and says the differences be tween them are mostly differences of temperament.

"Solti is the more temperamental, I think, more Hungarian perhaps. He is very exciting to work with. Karajan takes a line from the beginning to the end of the performance. He is a very strong man, and it is fantastic to perform with him and feel this force. He makes few gestures. He goes onto the podium and places his feet so! After he has conducted for an hour, his feet are in the same place. His concentration is almost superhuman. For me, he is one of the greatest musical personalities of our time. He is very loyal to singers who have worked well with him, such as Mirella Freni, Luciano Pavarotti, and Fiorenza Cossotto. He has great love and respect for singers, but since he himself always wants to give more and more, he demands the same thing from singers. When you succeed in giving him what he asks, there is a fantastic sense of collaboration, and it is no longer important that he is the conductor and you are a singer, but that you both make music together." When asked whether he preferred singing concerts to performing in op era, Van Dam paused and hedged a bit.

"In opera you may sing very well, but you have to do many other things too.

-------- VAN DAM ... "For me it is important that the audience

see Giovanni as a very dangerous man, and yet in a way a pathetic man.”---

You have to wear costumes and wigs and move and impersonate a character.

The public these days demands better acting from singers, and they are right to do so. Orchestral concerts or recitals of lieder and melodies offer the opportunity for greater musical concentration. You become like a violin or piano soloist and you can make pure, beautiful music. Opera does not permit this kind of concentration, and I feel that I make better music in concerts." We spoke a great deal about singing technique. Just as the pianist Artur Rubinstein says that he learned how to phrase from listening to such singers as Emmy Destinn, Van Dam says that he has learned a lot about singing from great instrumentalists, such as the cel list Mstislav Rostropovich, and the equalization of the voice in all registers is particularly important to him. "I am pleased when people tell me they hear continuation in my voice from low to high with no breaks. You have 4 musical line to follow and you must do that with the characteristics of your own voice. The voice is an instrument too, and it should not sound like a violin when you sing high and a cello when you sing low. I think a good singer is born with a voice, but he must learn how to work with it. A Stradivarius is nothing until you put it into the hands of someone like Arthur Grumiaux, Itzhak Perlman, or Pinchas Zukerman who can make music with it. The same is true of the singer." Van Dam is concerned not just with singing technique but also with the necessary preparation of individual roles.

He has sung Leporello in Don Giovanni for some time, but before adding the title role to his repertoire in 1976, he did a great deal of research. "For an important role like that you must have background. You need one hundred ideas about such a character although you may be able to convey only two or three on stage. I read everything I could find about Don Giovanni, particularly what the Danish philosopher Kierkegaard and the French author Jean Jouve wrote about the opera. For me, Giovanni is not just a man who chases women. He is not so superficial as that. My conception of the opera is mythic. Elvira, Anna, and Ottavio are mere people like you and me, but the Commendatore represents the forces of good and Giovanni those of evil. The Commendatore is killed, but he comes back. Giovanni dies in the end, but he too will come back throughout eternity.

I do not want the audience to think him a sympathetic character. He does everything for himself, and when it is necessary to kill, he kills. For me it is important that the audience see Giovanni as a very dangerous man, and yet in a way a pathetic man. He is afraid of death, but in death he finds what he is looking for. I think the death of Giovanni is the greatest musical and dramatic scene in Mozart's works." Van Dam has enjoyed singing at the Met, where he finds the working atmosphere very congenial, and he will re turn next season in Jean-Pierre Ponnelle's production of Wagner's The Flying Dutchman. "Singing here is a joy for me because the audiences are so open and warm. When I came here with the Paris Opera in The Marriage of Figaro, all the French singers agreed that we had better audiences here than in France. When you are on stage, you know when the audience is reacting to the work and to the performance, and this is a great stimulus to the singer. In some European theaters there is a snobbish atmosphere, and we had a period about ten years ago when young people were not interested in opera.

That is improving. But in this country there are many young people in the audience, and even the older people seem youthful. They are enthusiastic and demonstrative." LIKE most international singers these days, Van Dam spends a lot of time in recording studios, and he free-lances with a variety of the major labels Deutsche Grammophon, RCA, and An gel. He admits that he enjoys making records, but he has some reservations about them. "In the early days recording techniques could not completely capture the voices of Caruso, Melba, or Tito Schipa. Now we have wonderful electronic techniques, but some producers want to make recordings too perfect. If a singer has trouble with a high note in an aria, the producer may record that note ten times, choose the best one, and splice it in. For me that's lying. I think of recordings as calling cards for Beverly Sills, Placido Domingo, and Van Dam, and we must be honest and not write on those cards any thing that is not true. I never want someone who has enjoyed one of my records to come to the theater and find that I cannot do the same thing on the stage."

IF I were to choose among Van Dam's recordings, I would recommend the RCA Carmen and the Berlioz Romeo and Juliet for starters. But, like a true Virgo, Van Dam himself is self-critical and declines to choose. "My best recordings are the ones I will make in the future. Recording Romeo et Juliette with the Boston Symphony and Ozawa was a beautiful experience, but when I heard the record, I loved me not-not even the sound of my own voice! Per haps it is too soon for me to listen to my records and enjoy them because I am still singing the same repertoire and trying constantly to improve. Perhaps one day I can play them for my grand children and say, 'Listen to how well your grandfather could sing.' "You work so hard to succeed, and if you do, you have only a few years at your peak. The decline is slow but sure. You must never think 'Now I am at the top,' but continue as though your best is yet to come. And it is rare that a singer knows when to stop. There are so many who should have stopped long ago.

"Micheau tapered off, and toward the end she did only important things, ten or twelve performances a year in stead of fifty, and people said, 'What a pity that she does not sing more.' That's so much better than to have them say, 'Isn't it a pity that she is still singing.' I hope I will know when to make an end or that my wife and friends will tell me. It is important to have the applause and be surrounded by people and praise, but there always comes a moment after the performance when you are alone.

"I have my private life, my family, my home. For me it is important to distinguish between the man and the singer so that when the time comes after twenty or thirty years of a beautiful career and the singer must go, the man can remain and still love life."

Also see:

Link |

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)