By Steve Simels

ONCE upon a time, in those far away Days of Our Youth and Innocence when rock lyrics were looked upon as a form of literature roughly on a par with the stuff to be found in tattered old copies of Captain Billy's Whiz Bang ... when the average rocker-assuming he knew how to spell-did not feel compelled to reproduce every bit of his deathless poesy on the inner sleeve of his latest stack o' wax ... when the charts were dominated by Herb Alpert, The Sound of Music, and The First Family ... when album-cover art was 90 per cent cheesecake of the kind typified by Julie London kittenishly recumbent on a throw rug, some typing-pool Venus slathered with Instant Whip, or an anonymous Levantine dish abundantly decolletee in a Scheherezade suit, it didn't require a hell of a lot of intellectual moxie to dope out the credits on an average LP. Unless, of course, you were a functional illiterate (teenager) of the type railed against in Life magazine ("Why Johnny Can't Read, but Ivan Can!"), easily confounded even by something as simple as an artist's name, an album title, and (occasionally) a paragraph or two of fan-mag-style liner notes. Because that's about all you got.

This sorry state of affairs was hardly surprising, though, for several reasons, not all of which we need go into here.

One of them, however, was surely the fact that the pop LP was still being merchandised primarily as a useful adjunct to the hit single, a format whose tiny sleeve rarely permitted much more than a picture. But since pop music had not yet made the transition from High School to High Art, it didn't matter anyway. If only cretins listened to the stuff, as The Industry assumed, then it followed that only the brain-damaged would be interested in reading about who was responsible for creating it.

Jazz records, of course, were the snobbish exception, usually as copiously annotated as original-cast Broadway-show albums or full-fig classical efforts (although it is worth mentioning that some classical releases were conspicuously bereft of liner notes).

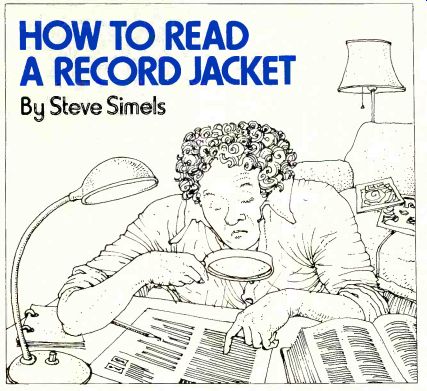

Still, like many of our most cherished institutions (the eight ways Won der Bread builds strong bodies, the De-Soto convertible, and the House Un American Activities Committee), the Album Cover as Vacant Lot has, since the Sixties, gone the way of the dinosaur and the complimentary cigarettes on airplanes. Today's LP's come replete with a numbingly extensive compendium of credits, blank verse, acknowledgments, biographies, dedications, in-jokes, lyrics, family snap shots, and so much general information that cover copy is frequently dense enough to recall a Modern Library edition of Jean Christophe or the complete works of Dickens in longhand.

That being the case, it is inevitable that the average consumer (as well as that functional illiterate referred to above) is often understandably con fused as to what exactly was done, by whom, and even why on, let us say, the well-worn copy of "Frampton Comes Alive" that he or she is perusing during third-period study hall. In pop music, sadly, as in so many other contemporary pursuits, jargon (such as "custodial maintenance engineer" for "janitor") reigns supreme. To clear the air, un-muddy the waters, and un-cloud the eye, then, I intend to supply forthwith a fair translation of some of the phrases frequently found lurking about the fronts, backs, sides, sleeves, and shrink wraps of these most potent of our current cultural icons. Bear in mind while reading that not once during the composition of this article did the author have occasion to avail himself of either an Aphex Aural Exciter or a state-of-the-art set of Synthidrums. I haven't figured out just what they are yet.

PRODUCER: In that innocent era before Snooky Lanson was publicly humiliated by having to sing Rock Around the Clock on the Lucky Strike Hit Parade, records were made under the watchful, beady eyes of a Tin Pan Alley refugee known as an A-&-R (for "artist-and-repertoire") man who told the poor puppet of an artist what song to sing, how to sing it, and when he could go home after the session. With the advent of Peace-love-and-flowers in the Sixties, Mr. A-&-R metamorphosed into something astounding, a groovy young dope-smoking guy who helped a group cope with the pressures of Total Creative Control and functioned as an equal partner in the creative process-say, Jimmy Miller as the sixth Rolling Stone. Today, as the Eighties hustle toward Los Angeles to be born and the concept of machine music makes its triumphant comeback, the producer has reverted to type somewhat: now he is a groovy young dope-smoking guy with beady eyes who tells the poor puppet of an artist what song to sing, etc.--say, Richard Perry as multi-platinum schlock-meister. All in all, however, be he hack, artiste, skilled technician, or visionary, his basic function is to sit in the control room and nod knowingly after the musicians have finished a take. Producers (and certain rock critics) like to think of the job as being akin to that of a film di rector-the Producer as Auteur, so to speak. Be assured, though, that this is mostly nonsense. Consider: if George Martin's production was what really made the Beatles, how come his records with American Flyer are so bloody boring?

SYNTHESIZER: An arcane electronic keyboard instrument that no body-but nobody-ever plays during the recording of albums by Queen. Just ask them.

CATERING: Since musicians are, on the average, just like everybody else, they suffer occasional Big Mac attacks as a result of their strenuous invocations of the muse, and more and more musicians are now plugging the eateries that relieve them. Chow's Kosherama catered Martin Mull's second album, while Southside Johnny and the As bury Jukes "ordered out" from Stars' Deli, even though they don't stay open past eleven.

ENGINEER: Most rock groups, owing to the sterile exigencies of contemporary recording techniques-Dolby, twenty-four-track consoles, Grammy Award nominations-spend endless hours of expensive studio time trying to re-create the raunchy sounds Link Wray achieved by accident in an ill equipped garage in 1958. The engineer (or knob-twirler, as he is known in professional circles) is the man who either helps them in this ceaseless quest for sonic shoddiness (if he's creative) or, finding the whole prospect as repellant as a poke up the nose with a burnt stick (if he apprenticed on Maria Muldaur sessions), does his damnedest to make the lead guitar sound less like a Sherman tank gone berserk and more like a two-dollar plastic ukulele. Obviously, this makes him extremely important to a rock band, especially if they're at all green about record making. The best engineers--Glyn Johns, for example often double as producers, which makes a great deal of sense ... particularly for artists who don't relish the idea of screaming at two different bozos about that ukulele that has mysteriously found its way into their latest work in-progress.

THE LONE ARRANGER: A Martin Mull-ism for the man ( Keith Spring) who wrote the horn charts on his semi-hit Dueling Tubas.

BACKGROUND VOCALS (not to be confused with Guest Appearances, which see): Any number of famous or not-so-famous celebrities (usually singers, although this is not a hard and fast rule) who drop by the studio to croon an occasional "ooh" or "aah" that will he intentionally buried by the surrounding din and all but inaudible when the record is completed. Liza Minnelli is credited as having appeared on Alice Cooper's "Muscle of Love," for ex ample, but her enthusiastic Las Vegas warblings have remained undetected even by those masochists who've seen The Act more than once. This particularly odious form of cronyism was originally pioneered by Stephen Stills, who once not only recorded a chorus consisting of David Crosby, Graham Nash, Joni Mitchell, John Sebastian, and Mama Cass Elliot, but somehow man aged to get them all to sound like clones of himself.

GUEST APPEARANCES: Come in all sizes and shapes. In the case of vocalists, they are usually in the form of unlikely duets, as when Bob Dylan popped up unexpectedly on Bette Midler's version of his Buckets of Rain.

With instrumentalists, we are often treated to pedestrian guest solos, a brilliant and famous exception being Eric Clapton's performance on the Beatles' "The Album Cover as Vacant Lot has, since the Sixties, gone the way of the dinosaur and the complimentary cigarettes on airplanes." While My Guitar Gently Weeps. For contractual (and other) reasons, many guest appearances are shrouded in a carefully calculated air of mystery; George Harrison has appeared as L'Arcangelo Misterioso, Al Kooper masqueraded briefly as the legendary Roosevelt Gook, and the Ramones, of late, have even passed as a rock-and-roll band.

SPECIAL THANKS: A chance to pay back old debts, acknowledge friends from the neighborhood, send secret love notes, discreetly let your cocaine dealer know how much you appreciate the wonderful work he's doing, or get even with all those you passed on the way up. New York punk rockers Tuff Darts said it best on the back of their first album: "Thanks to nobody."

SPIRITUAL GUIDANCE: Similar to Special Thanks, only in this case it's a nod to your priest, rabbi, guru, or (in the case of John Lennon) analyst. Pioneered by the Grateful Dead, who still don't know any better, and now irredeemably passé.

MIXING: After every one of those twenty-four tracks has been filled, whether they needed to be or not (by God, you pay your $7.98, you better get your money's worth!), the producer, the engineer, and the group, if they've got a good lawyer, sit around for a leisurely six months (anything less is considered inappropriate to the proper superstar arrogance) and try to sort it all into some kind of finished product suitable for FM airplay, giant bill boards on the Sunset Strip, and lip synching on the Mike Douglas show.

Many an album and many a friendship have been destroyed during this process, which has been aptly dubbed "mixing." Mott the Hoople organist Verden Allen, for example, upon hearing the final mix of the Hoople's third album and discovering that his solos were inexplicably missing, became so enraged that he broke producer Guy Stevens' jaw. Reactions like that have led to the latest technological break through: computer mixing.

SPECIFICATIONS: An obscure term, used only once in rock history, which describes the techniques and equipment used in the production of Lou Reed's two-record musique concrete masterpiece, "Metal Machine Music" (better known as "Excedrin Headache CPD2-1101").

TOM SCOTT: A virulent strain of musical flatulence, believed to have been perfected at Elektra/Asylum Records some time in the early Seventies, which has since afflicted innumerable chart-topping albums. The ailment is duly credited, and at times even its symptoms are described, but there's no known cure.

GOPHER: Better known in record circles as Associate Producer, the gopher is that dedicated and underpaid individual who is on call to provide the artist with food, cocaine, Dom Perignon, caffeine, the latest issue of the Hollywood Reporter, cocaine, new strings, nicotine, phone numbers of high-price session men, cocaine, good looking groupies, Clive Davis' phone number, and cocaine. In the real world, his closest equivalent is the vice president of the United States.

Also see:

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)