Optimizing a Deck

In your article comparing cassette decks in STEREO REVIEW'S 1978 Tape Recording and Buying Guide, you said that a tape's performance could vary widely depending on the internal adjustments of a given deck. I own a very good cassette recorder and want to have it "optimized" for a specific tape. What sort of work is involved in this? I've asked two servicemen about it, and one quoted a price I thought was ridiculously high while the other was willing to do it for a figure that seemed suspiciously low.

ROBERT HOBART Los Angeles, Calif.

A. While I normally settle for margarine, this is one time I might recommend the "high-priced spread." Doing a complete "set up" job on a tape recorder-especially a two-head cassette machine, where you cannot continuously monitor the results of each adjustment as you go but must instead record tape with .a "spread" of adjustment settings, rewind it and play it through again to find which was "optimal," and then set the deck to that-is a time-consuming task. There are several different adjustments involved, and some of them interact with one another.

Assuming the primary playback adjustments are correct, there are four principal record adjustment areas. The first is bias current, which should vary with the tape type and with the recorder's tape head; it affects high-frequency response, mid-frequency tape sensitivity, distortion, and signal-to-noise ratio.

Your low-bidding technician probably intend ed to make only this adjustment.

The second adjustment is record equalization, which is essentially the amount of treble boost needed to produce acceptably flat frequency response once the bias current has been set. Unhappily, bias and equalization are interrelated in their effects on high-frequency response, and this must be taken into account in the adjustment. On some cassette decks the record equalization is not adjustable; on others, there may be two different controls for it for each channel.

Third, the recording-level meters must be calibrated to reflect the "headroom" (the difference between an indicated "0 VU" and the onset of serious distortion) dictated by both the tape and the amount of mechanical lag in the meters' response to the various signals.

Fourth and finally, the Dolby system must be calibrated to reflect the sensitivity of the tape you have chosen. For a specific input level, different cassettes produce different playback-output levels, and for the Dolby system to function accurately it too should be matched to the selected tape.

Your particular deck may contain even more record adjustments than these-and, frankly, I wouldn't touch a record section until after I had thoroughly checked out the playback adjustments. So you can see that "optimizing" for a given tape can be a fairly extensive (and expensive) operation. It would probably make more sense to experiment a bit and determine by trial and error which tapes perform best with your deck using the internal adjustments it already has.

Dolby-calibration Tapes

Q. I got a "Dolby-level" test cassette from a LC manufacturer to calibrate my several Dolby decoders, but it shows the same wide (5- to 6-dB) variations between channels on three different recorders, so I think the tape is defective rather than the machines.

Getting an accurate Dolby-calibration cassette seems almost impossible. Can you help?

A. REISMAN; Yorktown Heights, N.Y.

A. While any test tape might be defective and every one will eventually lose its calibration accuracy through use-both my mail and that received at Dolby Labs indicates that there are a fair number of badly-made Dolby-level calibration cassettes floating around. The Dolby people have therefore begun to compile a list of suppliers of accurate Dolby-level cassettes; prices range from about $7 to $20. To date, the list includes:

RMS Inc., 7 Maynard Drive, Oakridge, N.J. 07438.

RCA Special Products, 6550 East 30th Street, Indianapolis, Ind. 46219 (part No. 127).

Standard Tape Laboratories, 26120 Eden Landing Road, No. 5, Hayward, Calif. 94545.

Marantz, 20525 Nordhoff Street, Chats worth, Calif. 91311 (part No. 897-5001-000).

TDK Electronics, 755 Eastgate Boulevard, Garden City, N.Y. 11530 (part No. AC-317).

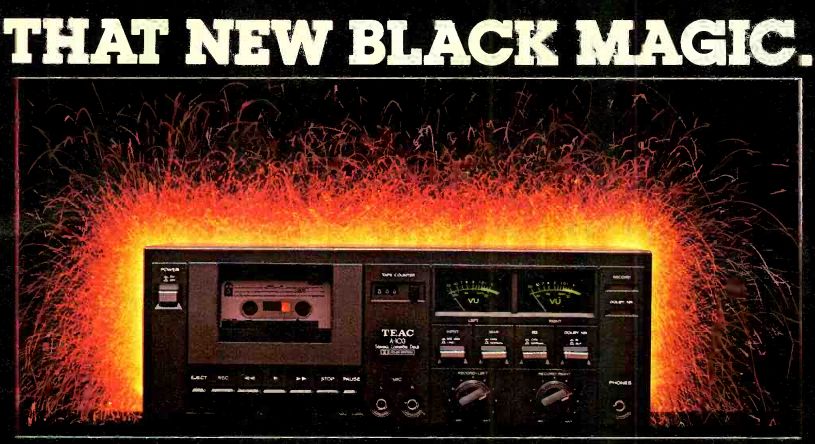

Teac Corp. of America, 7733 Telegraph Road, Montebello, Calif. 90640 (part No. MIT-150).

Some of these manufacturers may be interested in handling only industrial quantities (you'll have to write to find out), but at least one (TDK) advertises that its Dolby calibration tape is available through the audio dealers who handle its products.

Critical Difference

Q. I chose my open-reel recorder because I was told that it is one of the cleanest-sounding decks around. Yet when I am A-B monitoring with it (or with any other recorder, for that matter), the incoming signal always sounds somehow easier to listen to than the playback signal. Is this because of intermodulation distortion-specifications for which are never given (or at least I've never seen any) for tape recorders?

DONALD R. LOOSE; Fairborn, Ohio

A. Intermodulation distortion (IM) is generally considered more audibly unpleasant than harmonic distortion, because the distortion frequencies generated by intermodulation are normally not related in any "harmonious" way to the original signal frequencies.

Harmonic distortion creates simple frequency multiples (harmonics) of the original tone(s), whereas IM creates new tones whose frequencies are the sum of or the difference be tween the originals.

I don't think that the absence of IM specifications for tape equipment signifies any de liberate "cover-up" on the part of recorder manufacturers. Mainly, this is because IM distortion is a problem inherent more in the tape itself than in the recorder(s) it is used with, so a single "IM spec" for a given ma chine won't have much meaning. Moreover, there are three or four widely used methods of testing for IM, making comparisons between such specs given by different manufacturers difficult. (An IEC standard test method has been proposed, but it has not yet been universally adopted; if it is, you'll get full particulars in this column.) My own experience is that the test method I use always results in higher percentages for IM than for harmonic distortion, but I have not found much significance in the difference for open-reel recording, only for cassettes.

One reason for this, I think, is that the kind of harmonic distortion typically generated by the tape-recording process--that is, the addition of spurious odd harmonics (the third, fifth, seventh, etc.)--sounds much like IM distortion. Even harmonics, which do not tend to be generated in tape recording, are like ordinary musical overtones, and thus sound "consonant" to most ears. The difference is similar to that between the sounds of square and sine waves; the former has an unpleasant raspy or buzzy quality like the distortion typically found on recorded tapes.

In your case, Mr. Loose, I think that the distortion you hear when you compare source and playback using a top-quality open-reel deck includes not only IM and odd-harmonic distortion, but modulation noise as well. This is a. factor considered more often in professional than in home recording circles. Unlike the noise that gets measured in order to determine a tape recorder's signal-to-noise ratio, modulation noise exists only in the presence of a recorded signal. One hears it as a noise "behind" the signal, and since its intensity varies directly with the intensity of the signal itself, it can't be masked by recording at a higher level.

There are two principal kinds of modulation noise; in a particular case, both may be present to varying degrees. One is a type of frequency modulation (FM) arising from physical vibration of the tape as it passes over the heads; this effectively varies the rate of tape travel and causes frequency variations too rapid to register on wow-and-flutter meters.

Such FM tape noise is usually called "scrape flutter," and it can often be reduced by special rotating "scrape-flutter filters" installed next to the tape heads (provided that these are properly designed and suit the type of tape being used).

The other kind of modulation noise is an amplitude modulation (AM) of the signal that is caused by magnetic irregularities in the tape itself-particularly the irregularities near the surface. AM tape noise thus varies widely from one reel (or brand) of tape to another.

Since it is best measured by recording a d.c. signal (0 Hz), it is often called " d.c. modulation noise," but it affects regular audio frequencies as well. With some tapes a small variation in the bias level can markedly reduce such noise, but it is very difficult to pinpoint the optimum variation without appropriate test instruments, making this solution impractical for most non-professional recordists or audiophiles.

In short, Mr. Loose, there are plenty of potential sources for the noise you hear, but put ting one's finger on the precise cause is not at all easy. However, since the tape itself is the likeliest culprit, you might, as a start, try switching to another type.

Tape Timers

Q. Why is it that no manufacturer of tape recorders includes an electronic minute timer? The tape is offered in 30-, 60-, and 90-minute versions, but the "index counters" on tape decks have nothing to do with playing time and those on different machines don't even agree with each other. Would a real timer cost that much extra?

HARRY S. FALKOFF; Branford, Conn.

A. There are, in fact, a small number of . tape decks, both cassette and open-reel, whose timers read out in "real time" actual seconds and minutes-but it is still much cheaper to provide a "counter" that responds to the number of revolutions of either the take-up or supply reel. Since the number of these revolutions in a given time varies ac cording to the amount of tape, on the spool, there is no accurate way to correlate index-counter readings with actual playing time, whether elapsed or remaining. Further, despite attempts by groups interested in standardization, even the typical index counters don't agree from machine to machine, as you note. But with the cost of electronics technology dropping, more true timers should be coming along. Sharp and Optonica both offer cassette decks with liquid-crystal digital tape timers that also serve as 24-hour clocks.

Also see:

Link | --Technical Talk

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)